|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 22, 2014 21:39:14 GMT 5

Well, that’s subjective.

It’s valid to argue that predominantly piscivorous and theutivorous diet classifies as a lower trophic level, but that’s mainly because the pinnipeds that make up a large part of Carcharodon’s diet are not available in pelagic habitats, not because of predatory power (since the larger prey items of both are comparable).

The point is, we don’t know how an encounter between both would end (in other words, which one would be the dominant one in terms of predatory power if they faced each other), because there are no documented cases.

|

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Jul 22, 2014 22:20:12 GMT 5

That's objective to me. The great white shark attacks and kills, albeit not frequently, preys items larger than the largest preys items of Pseudorca. Calves of large baleen whales, bull seal elephants, others white sharks individuals have been known to fall prey to Carcharodon occasionnally, and Carcharodon makes the kill alone. So, based on the size of preys items and the fact that Carcharodon likely reaches sizes a bit larger than Pseudorca, even if these record cases are difficult, let me to strongly believe that globally Carcharodon is the superior predator, either in terms of trophic dominance or destructive power. Anyway, Carcharodon is always placed either as the first or second top predator behind the orca in oceanics food chains, Pseudorca being never included in it.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 22, 2014 22:37:03 GMT 5

Which would be a good time to collect some accounts of those feats, but they belong into another thread.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 23, 2014 2:03:48 GMT 5

False killer whales are opurtunistic feeders and specialize in fish and squid (some quite large, possibly equivalent to great white shark predation on pinnipeds), those being the most readily available prey in their habitat, but they seem to attack just about everything a great white can attack, including pinnipeds, dolphins and even large whales. There are recorded attacks on adult sperm and humpback whales, and a young humpback whale has been recorded as a prey item, but I could not find details (supposedly it’s in Hoyt 1983). I don’t see sharks as trophically superior predators to same-sized odontocetes, although there may be some niches they are better suited for (theorethically giant prey, but the only recorded instance I know is a tiger shark eating and dealing fatal damage to a sick blue whale). Btw based on what exactly do you consider pygmy killer whales the most formidable odontocetes at size parity? Have a look at reference 4, their jaws seem proportionately smaller, are more gracile and have much smaller dentition than Orcinus or Pseudorca.

1. www.researchgate.net/publication/230250139_ATTACK_BY_FALSE_KILLER_WHALES_%28PSEUDORCA_CRASSIDENS%29_ON_SPERM_WHALES_%28PHYSETER_MACROCEPHALUS%29_IN_THE_GALPAGOS_ISLANDS2. animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Pseudorca_crassidens/#8facdbf289b57f52667a5a99e1bf3b373. www.cms.int/reports/small_cetaceans/data/P_crassidens/p_crassidens.htm4. ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/009/t0725e/t0725e19.pdf |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Jul 23, 2014 2:20:46 GMT 5

I consider pygmy killer whales the most formidable simply due to their unique agression level toward others marine mammals of similar or larger size. One individual captured and placed in a tank with two pilot whales killed the pilot whale calf in one ram. They're small but are known to attack dolphins their own size. They've also targetted humans.

Pseudorca kills are mainly in pods whereas Carcharodon kills alone. Added that Carcharodon reaches slightly but not unsignificantly larger sizes, weight wise, Pseudorca is athletic but notoriously more slender than an adult Carcharodon of comparable length, the later is therefore IMO superior to Pseudorca. Pseudorca is never placed as the second global oceans top predator behind O. orca, Carcharodon is. That does not mean it is not a dangerous adversary to Carcharodon, especially since it lives in pods.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 23, 2014 3:22:46 GMT 5

Aggression levels are not everything, an animal also needs killing tools in order to be a formidable predator. Have a look at the document I posted (ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/009/t0725e/t0725e19.pdf). On page 5, there’s the skull and lateral view of a pygmy killer whale, note the differences between it and the macrophagous dolphins (page 3, also: ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/009/t0725e/t0725e18.pdf). The jaws of the pygmy killer whale are proportionately smaller and more reminiscent of a pilot whale in shape. That even the rams of small dolphins can be very potent and potentially fatal has already been documented (that’s why this thread even exists, isn’t it?), but in terms of physical attributes killer whales and false killer whales are more impressive than pygmy killer whales, irrespective of their size. |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Jul 23, 2014 3:52:13 GMT 5

Not in my opinion, the agression level of this tiny cetacean, killing any other marine species in the same tank, with one individual killing a pilot whale calf in one sharp blow makes it at parity a fiercer, more engaging fighter than others, again that's only my opinion, not a rigorous claim. No matter its killing apparatus is less developped than in its relatives, I'm impressed by Feresa.

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Jul 27, 2014 9:29:17 GMT 5

Mako sharks are known to take dolphins of comparable sizes to themselves. The first two videos are of the same encounter. In the second video, you can see the shark carrying the spinner dolphin. It's hard to tell for sure, but it looks like the dolphin is similar in size to the shark, but has had its tail bitten off. The third video shows a predation on what's described as a bottlenose dolphin, but it's not easy to make a precise size comparison. The shark does look bigger, but again the dolphin is missing its back end.

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Jul 27, 2014 9:37:09 GMT 5

Possible great whites' predatory attacks on a pod of pilot whales.

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Jul 27, 2014 9:51:13 GMT 5

Healed shark bite wounds on a false killer whale in Hawaii. From the website www.cascadiaresearch.org/hawaii/july2010.htm The researcher states with reference to this picture: "False killer whale with recent shark bite wound and a long-term injury to the dorsal fin, August 5, 2010. Photo by Dan McSweeney. This individual is HIPc127 in our catalog, first documented off Maui in March 2000 (with the bent dorsal fin), and seen several times since both off Maui and the island of Hawai‘i. The shark bite wound behind the dorsal fin is the first time we've documented evidence of an attack by a large shark on a false killer whale in Hawai‘i. " |

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Jul 27, 2014 10:27:14 GMT 5

Possible bull shark predation attempt in Brazil. Bull sharks are well known to prey on dolphins. From the journal: "Interactions between sharks (order Selachii) and dolphins (order Cetacea, suborder Odontoceti) have been reported worldwide (see Heithaus, 2001 for a review of shark predation on dolphins). Such interactions are usually reported from the investigation of stomach contents, from occasional opportunities witnessed in the field, and from observations on wounds and scars on living and dead scavenged individuals. Heithaus (2001) showed that the remains of at least 24 toothed whale species were already found in shark stomachs, but S. guianensis was not listed. On 16 February 2008, during one of the survey days in Canal do Superagui, an adult Guiana dolphin was photographed without its dorsal fin in a group of 20 individuals composed of 14 adults and 6 calves, all photographed. A detailed analysis of the photographs (see Figure 3) showed that the wound was certainly provoked by a shark bite, probably the result of a failed predation attempt. However, it was not possible to ascertain the species responsible for the unwitnessed attack, as well as to know if the attack occurred in inner or outer waters. The bull shark, Carcharhinus leucas (Müller & Henle, 1839), commonly found in local coastal waters and already found in inner estuarine waters of Cananéia (Sadowsky, 1971), and listed as a regular predator of small cetaceans (Heithaus, 2001), may be listed as a potential candidate for the observed bite. An investigation on the feeding habits of several shark species found in local (inshore and offshore) waters may render more clues on their possible interactions with S. guianensis. According to Heithaus (2001), to understand group sizes and habitat use of dolphins, it is important to understand the relative risk to an individual odontocete from predators, particularly sharks, in different habitats."  |

|

|

|

Post by Ceratodromeus on Dec 3, 2015 22:59:16 GMT 5

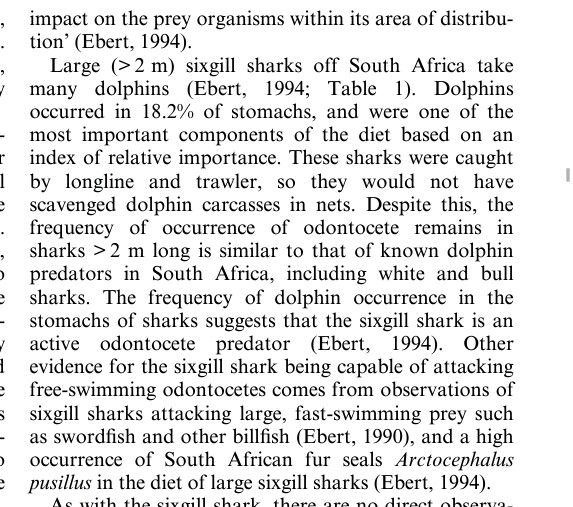

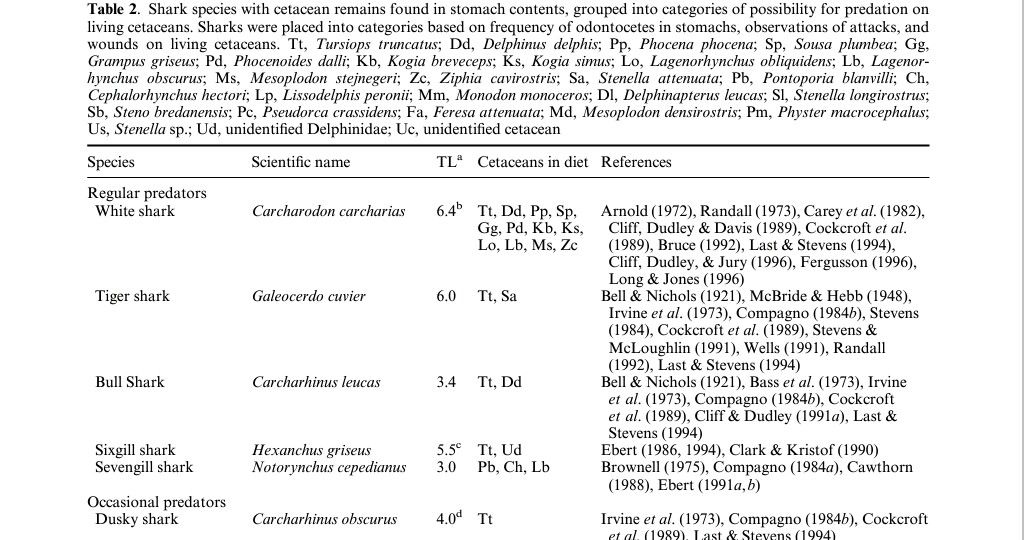

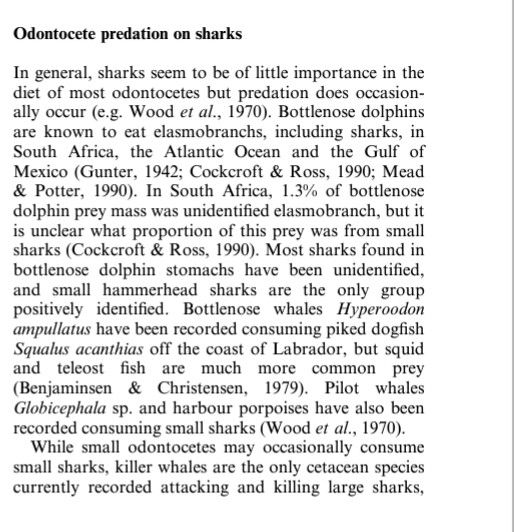

The paper 'Predator–prey and competitive interactions between sharks (order Selachii) and dolphins (suborder Odontoceti): a review.' Is a pretty good reference point for this thread; i'll post the screen shots I've taken here Sixgill predation on dolphins  (Species predated are mentioned below)  Interesting bit on dolphins predation sharks  |

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Dec 19, 2015 1:00:02 GMT 5

We all know that orcas generally dominate all sharks. But it's still a comparatively dangerous prey/opponent/competitor, even for the largest delphnid. Here's an article and picture of John Coe, an iconic and large male orca who lives off the coast of Scotland. He's recently been seen with a significant crescent shaped bite out of caudal fin that very clearly suggests a shark bite. No idea which species did this, it's too small for an adult great white shark or another orca, but still a fairly sizeable (and probably painful) wound. Moreover, GWS are not commonly around such cold waters. A large salmon shark perhaps? The article calls it a "shark attack" but I would guess more likely was a defense from predation, which the shark could have still very easily lost, particularly if the whole pod was involved in the hunt. But still, it shows the sharks are not a prey/competitor to be trifled with, even for orcas. www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-30980599

Shark attack suspected on killer whale John CoeA shark has been suspected of biting a chunk out of the tail fluke of a killer whale well-known to whale and dolphin watchers in Scotland. Nicknamed John Coe, the male orca can be indentified by a notch on its dorsal fin. The injury to its tail was spotted during a survey by the Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust (HWDT). The trust said consultations with experts suggested that it was "almost certainly" caused by a shark. John Coe is one of a small community of orcas regularly seen off Scotland's west coast. Members of the group have also been spotted at times off Peterhead and Girdleness in Aberdeenshire, Ireland's west coast and off Pembrokeshire in Wales. Image caption John Coe can be identified by a notch on its dorsal fin The group, which is believed to be the UK's only resident population of killer whales, is thought to contain just nine older animals. There are fears that it will eventually die out after becoming isolated from other killer whale populations. In a statement, the trust said: "Notable highlights during 2014 included two separate encounters with what is believed to be the UK's only known resident population of killer whales. "This small, isolated population of orca has never produced offspring since studies began, raising fears that it faces imminent extinction." Image caption A young minke whale was spotted during the recent survey It added: "Evidence of drama emerged when one of the group's males - known as John Coe - was observed with a large area of his tail fluke missing. "Consultations with experts suggest that this was almost certainly the result of a shark attack." The trust said it could not "realistically speculate" on the kind of shark involved. HWDT carried out its latest survey of whales, which included a young minke whale, dolphins, porpoises and plankton-feeding basking sharks, between May and October last year. The trust has now released information on the data it gathered, including a 25% increase in sightings of harbour porpoises and a 33% decline in observations of basking sharks. |

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Dec 22, 2015 21:14:12 GMT 5

Follow up article where marine biologist Dr Yannis Papastamatiou surmises that a mako shark was the most likely to have bitten the male orca in question. I didn't realize makos traveled so far north, but apparently they are not uncommon in Scotland, far more common than a great white. I think the mako is the most probable culprit, rather than my earlier speculation regarding a salmon shark. www.deadlinenews.co.uk/2015/01/28/mako-inflicted-orca-bite-says-expert/ |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jan 2, 2016 21:39:51 GMT 5

Jaws -- 4 million BC: How an extinct shark attacked its preySkeleton of the dolphin, preserved for 4 million years with the bite marks across its ribs from the shark attack the killed it. Credit: Giovanni Bianucci![]() It might sound like a mashup of monster movies, but palaeontologists have discovered evidence of how an extinct shark attacked its prey, reconstructing a killing that took place 4 million years ago. It might sound like a mashup of monster movies, but palaeontologists have discovered evidence of how an extinct shark attacked its prey, reconstructing a killing that took place 4 million years ago.

Such fossil evidence of behaviour is incredibly rare, but by careful, forensic-style analysis of bite marks on an otherwise well-preserved dolphin skeleton, the research team, based in Pisa, Italy, have reconstructed the events that led to the death of the dolphin, and determined the probably identity of the killer: a 4-meter shark by the name of Cosmopolitodus hastalis.The evidence, published in the latest issue of the journal Palaeontology, comes from the fossilised skeleton of a 2.8-meter-long dolphin discovered in the Piedmont region of northern Italy. According to Giovanni Bianucci, who led the study: "the skeleton lay unstudied in a museum in Torino for more than a century, but when I examined it, as part of a larger study of fossil dolphins, I noticed the bite marks on the ribs, vertebrae and jaws. Identifying the victim of the attack was the easy part -- it's an extinct species of dolphin known as Astadelphis gastaldii- working out the identity of the killer called for some serious detective work, as the only evidence to go on was the bite marks." The overall shape of the bite indicated a shark attack, and Bianucci called in fossil shark expert Walter Landini. "The smoothness of the bite marks on the ribs clearly shows that the teeth of whatever did the biting were not serrated, and that immediately ruled out some possibilities. We simulated bite marks of the potential culprits and, by comparing them with the shape and size of the marks on the fossils, we narrowed it down to Cosmopolitodus hastalis." Circumstantial evidence also supports this verdict: fossil teeth from Cosmopolitodus are common in the rock sequences that the dolphin was found in. "From the size of the bite, we reckon that this particular shark was about 4 m long" says Landini. Detailed analysis of the bite pattern allowed the researchers to go even further. "The deepest and clearest incisions are on the ribs of the dolphin" says Bianucci, "indicating the shark attached from below, biting into the abdomen. Caught in the powerful bite, the dolphin would have struggled, and the shark probably detached a big amount of flesh by shaking its body from side to side. The bite would have caused severe damage and intense blood loss, because of the dense network of nerves, blood vessels and vital organs in this area. Then, already dead or in a state of shock, the dolphin rolled onto its back, and the shark bit again, close to the fleshy dorsal fin." The study is significant because of the rarity of such 'fossilized behaviour'. According to Dr Kenshu Shimada, fossil shark expert at DePaul University and the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in the US, "studies like this are important because they give us a glimpse of the ecological interactions between organisms in prehistoric seas. Shark teeth are among the most common vertebrate remains in the fossil record, yet interpreting the details of diet and feeding behaviour of extinct sharks is extremely difficult. Fossil remains of prey species with shark bite marks, like those described by Bianucci and his team, provide direct evidence of what each prehistoric shark ate and how it behaved."

Killing in the Pliocene: shark attack on a dolphin from ItalyGIOVANNI BIANUCCI, BARBARA SORCE, TIZIANO STORAI and WALTER LANDINI " Shark bite marks, including striae, sulci and abrasions, in a well-preserved fossil dolphin skeleton referred to Astadelphis gastaldii (Cetacea , Delphinidae ) from Pliocene sediments of Piedmont (northern Italy), are described in detail. The exceptional combination of a fossil dolphin having a significant part of the skeleton preserved and a large number of bite marks on the bones represents one of the few detailed documentations of shark attack in the past. Most bite marks have been referred to a shark about 4 m long with unserrated teeth, belonging to Cosmopolitodus hastalis , on the basis of their shape and their general disposition on the dolphin skeleton. According to our hypothesis, the shark attacked the dolphin with an initial mortal bite to the abdomen from the rear and right, in a similar way as observed for the living white shark when attacking pinnipeds. A second, less strong, bite was given on the dorsal area when the dolphin, mortally injured, probably rolled to the left. The shark probably released the prey, dead or dying, and other sharks or fishes probably scavenged the torn body of the dolphin." Link

|

|