|

|

Post by Grey on Sept 3, 2019 23:14:39 GMT 5

Well, no large marine predator is "exclusively macrophagous". Orcas or great whites eat lots of juvenile seals, penguins and fish. By all means, Foffa et al. are certainly right to consider a prey item half the predator’s body length to already be quite large, even if I disagree that this is the largest a pliosaur could take. Yes but it depends the ontogenic stages and populations. I doubt that transient orcas and Deep Blue-sized GWS have great interest in prey items weighing 3 kg. While even large crocodiles on the other hand, convergent with pliosaurs, seem to be far more opportunistic and as eat as well small fishes and buffaloes once they are 5 m or more. I don't think a subadult 15 tonnes Otodus megalodon would have been as dangerous for a diver as the Aramberri pliosaur. |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Sept 3, 2019 23:17:09 GMT 5

Judging by scaling to actual measurement and measuring the same in both, actual greatest skull width seems more like 130 vs 90cm. You can really appreciate in this how Sachicasaurus’ skull may only be 25cm longer than that of P. kevani, but it is way larger overall. Good job. That is why I think Sachicasaurus bite force figures derived from Foffa. 2014 are likely underestimates given the sheer difference in robustness with P. kevani. I would even say even if it outmatched by Livyatan, it is not pathetic in comparison. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Sept 4, 2019 2:21:18 GMT 5

Well, needless to say that all bite force figures derived from Foffa et al. are likely underestimates, but that applies equally to bite force figures from Wroe et al., Snively et al. or any other study that used the dry-skull method, although not necessarily always to the same extent, which is why we should both compare apples to apples and remain aware of the high uncertainty involved with any and all these estimates.

However I get your meaning, the Sachicasaurus skull obviously looks far larger than the mere 13% difference suggested by the midline skull lengths, which is due to its greater width, larger maximum skull and mandible length and more robust rostrum. However it is beyond our abilities to tell with any degree of reasonable certainty how much we should appropriately scale the bite force, so let’s just say that 62kN is more of a lower-bound until someone attempts to model its bite force directly. Even so, possibly the hardest-biting reptile that we have a skull of.

Transient orcas might not, but resident orcas have an interest in salmon, don’t they? Deep blue is a freak, I don’t think anybody has even studied what great whites that size prefer to feed on. Certainly adult great whites transition to primarily rely on mammal prey, but the majority of that mammal prey still tends to be fairly small, certainly far smaller than the shark.

Orcas (not sure what type) like to eat penguins…

Where does McHenry record a 3kg prey item btw? The smallest he lists evidence from stomach contents for is the ~20kg turtle. He also lists some evidence of rather impressively sized prey (even a 300kg plesiosaur is not small, let alone a 1-2t one, and judging by the number of records with respect to all directly attested prey items, this doesn’t seem like rare behaviour). For sure pliosaurs were opportunistic feeders, what I doubt is that this is so special for a large marine predator; even if they do take very large prey regularly, this still doesn’t mean they would pass up any opportunity to eat something smaller if it swam by.

I don’t think a freak like Gustave hunts small fish, but I might be wrong on that.

A pliosaur would have an easier time catching such a prey item due to its better maneuverability, flexible neck and long snout. But I don’t see a 15t shark really struggling in that scenario either. The size ratio is probably not that different than with some of the seals great whites manage to catch, the shark is not much bigger than an extremely large orca, and a human diver doesn’t offer much in the way of evasive maneuvering.

|

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Sept 4, 2019 3:14:23 GMT 5

It all depends what we mean by macrophagous.

If I m not wrong, Foffa (or another) reports squids in the stomach contents in a specimen of the GWS-sized Liopleurodon. I doubt 5-6 m white sharks regularly prey on squids or fishrs that size, but apparently Liopleurodon could. I think, as you hint, this would have to do with maneuvrability and the shape of the rostrum, well adapted to this in Liopleurodon.

Damn, I can't find the prey size range but I'm pretty sure it is in the thesis, McHenry did it by direct analogy with modern predators with a long rostrum.

Yes some prey items of large white sharks are still mostly smaller but appear very rarely to be small-sized fishes and squids.

With their long rostrum, pliosaurs were more able to exploit this niche than lamnids. No wonder why pliosaurs were successful for so long...

Given how a 7 tonnes Kronosaurus appears to have eaten prey items of 20 kg and less, while modern GWS tend to favor rich caloric preys, I'm pretty confident that my chances of survival are a bit higher with the 15 tonnes shark, unless it becomes too curious.

On the other hand, a 10-15 tonnes pliosaur would not hesitate.

I think this is no myth to say that most of the apex carnivore marine reptiles, had we evolved with them, would have been extremely dangerous predators for unarmed divers, more than anything today.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Sept 4, 2019 4:29:48 GMT 5

It all depends what we mean by macrophagous. If I m not wrong, Foffa (or another) reports squids in the stomach contents in a specimen of the GWS-sized Liopleurodon. I doubt 5-6 m white sharks regularly prey on squids or fishrs that size, but apparently Liopleurodon could. I think, as you hint, this would have to do with maneuvrability and the shape of the rostrum, well adapted to this in Liopleurodon. That is very interesting indeed. Ok, but that’s a very different type of evidence then. If it’s not proven by stomach-contents of bite marks, then it is a mere hypothesis, and in this case a rather speculative one. Not that I find it unrealistic, just that I thought your original post implied it was factual that Kronosaurus had been recorded preying on animals that size in an equivalent way to how modern predators might be recorded doing it. Well, the question is then, how often did pliosaurs feed on such small animals? Well, we obviously know what plesiosaurs were successful for the longest time, and what plesiosaurs were actually well adapted to feed on small fish or squid; the long-necked forms. Now no doubt a pliosaur (or macrophagous shark, or odontocete) could eat and catch a squid too, at least a reasonably large one, but I think to say pliosaurs are morphologically predisposed to such prey is an exaggeration. Rather it seems pretty clear large pliosaurs are heavily adapted towards rather large prey (large bite forces, shearing jaw structure, large, often carinated and serrated teeth). But simply, as apex predators they would not have been able to focus on only a select few large-sized taxa, which would likely not have sufficiently reliable availability, but eat pretty much anything they could catch…just like extant marine apex predators, and just like megalodon, which was also recorded preying on turtles or pinnipeds, and presumably Livyatan. There is a loss in biomass of approximately 90% from one trophic level to the next. Feeding on only very large prey items (at least in the marine real, where large prey items are often at higher trophic levels because there are few macroscopic herbivores). A predator can get by only feeding on small fish, but it probably cannot get by exclusively feeding on the elasmosaurs that feed on the small fish. Rorquals that specialize in krill may be a special casem since they are technically at a very low trophic level, although on the other hand they are also very large and long-lived, so they likely still convert the energy they get from their food into biomass rather inefficiently (and are not overly abundant, as can be seen from the drastic impact of whaling that manifested itself long before the impact of overfishing on smaller taxa with larger population sizes became apparent). An estimated 5.7 ton Kronosaurus ate a 20kg turtle. An ~11 ton Kronosaurus are a ~300kg plesiosaur, and there’s evidence from bite marks of predation on a 1-2 ton plesiosaur. So by all means, it appears to have eaten prey items of 20kg and more. I don’t think the shark would hesitate either, although I could imagine it giving up or getting distracted by other prey more easily since a human-sized prey item would be energetically even more insignificant. On the other hand, a 15 ton megalodon would presumably still be quite young, so if this species had a dietary shift like great whites, maybe smaller individuals would have been more willing to go after smaller prey too than the large adults. Eating you would definitely bring in more calories than it would burn though, so I don’t think any hungry predator would pass up the opportunity if it presented itself. It’s pure speculation to say how any of these animals (even the relatively recent ones with close relatives) would have behaved towards humans. From megalodon and Livyatan, one might expect relatively little aggression towards humans, because their extant relatives show relatively little. However, these are still very different animals. Brown bears and polar bears behave totally differently towards humans too (why being a paleontologist in Spitsbergen is a dangerous job), and are even more closely related. You might guess that pliosaurs or other reptiles would behave more aggressively towards humans because extant crocodiles are known for their aggression towards humans, but in the end of the day a pliosaur and a crocodile are still totally different animals, and most pliosaurs would never have eaten any mammal, let alone have any experience with humans. Even for an extinct crocodilian, I would not know how it might have behaved towards humans. My rule of thumb would be, "if hungry, eat, if not hungry, ignore", which applies to all of these predators equally, even if certain extant predators don’t even seem to like humans as prey when they are evidently hungry. |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Sept 4, 2019 5:10:47 GMT 5

I will search about this quote by McHenry about prey size range.

It seems at least some medium-sized pliosaurs ate regularly squids (Liopleurodon) and the contents of the ~6 tonnes Kronosaurus studied by McHenry. These ones appears to have been regular.

I talked about pliosaurs as a group.

To quote McHenry :

"If longevity is any measure of success, then the pliosaurs must count as one of the

most successful groups of vertebrate of all. From the beginning of the Jurassic

Period until at least half way through the Cretaceous – a period of 115 million years –

pliosaurs were a consistent component of marine ecosystems, occupying the same set

of niches worldwide."

A propencity to be that opportunistic and not too much specialized (sometimes attributed to meg) is probably one of the reasons of their success.

I need to find this again, but this range is, IIRC, scaled up from large skulled crocs ecology.

The bite marks on turtles or small prey items could easily have been made by juveniles sharks or simply even non-meg sharks. And they are vastly less common than bite marks on mysticetes... that is the point.

Preying on pinnipeds is very vague, I only recall an ear bone of a fossil sea lion preyed upon by megalodon but here again the shark could very well have been modest-sized and pinnipeds can be pretty good-sized. A 500 kg sea lion is not the same thing as a 20 kg turtle and could satisfy even a 50 tonnes shark.

I simply don't envision a 50, 30 or even 10 tonnes shark spending energy to prey on 100 kg prey items. Megalodon appears more and more to have focused primarily on mysticetes, which were smaller than today, but from which even the smallest were probably larger than any of the prey items found in the Kronosaurus specimen.

Added to the squids in stomach contents of Liopleurodon, I rather believe it is safe to say pliosaurs were more opportunistic and preyed over a larger range of prey than meg, just like large crocs prey as well on 1 tonne mammals and smaller fishes while adult great whites focuses on marine mammals and large fishes.

Yes their jaws have obviously evolved to be powerful to tackle large, strong animals but they are also elongated, allowing them to seize smaller and more elusive preys. McHenry talks about that extensively.

Pliosaurs simply were better adapted to prey on a broad range of prey.

Not to say, megalodon was exclusively big game hunter but either stomach contents of modern white sharks and the predominance of bite marks on mysticetes suggests it was less adapted to prey on proportionately more modest animals. Which does not mean it never happened.

As for Livyatan, I suspect more and more it was a more pelagic carnivore, and that with its spermaceti, it could have preyed on beaked whales (found in the same area in Soutj Africa), pelagic sharks and possibly large squids.

We know at least one specimen preyed on things 285 times smaller than itself.

This is a similar disparity to what is seen between male Physeter and large squids.

I don't think this disparity has been observed between 5 m GWS and their prey or if so, uncommonly.

I base the idea that megalodon would have less interest based on modern GWS which are known to need highly caloric preys and based on the fact that GWS can be relatively docile toward divers.

A 15 tonnes meg would be 158 times heavier than me.

The question is have we seen a 1 tonne GWS preying on a 6 kg live prey item ?

I doubt about that.

However a much higher disparity is recorded both from crocs and pliosaurs... thanks to their rostrum combining brute force and precision.

Good point, we don't know how these animals really behaved, I simply look at the known size range of their prey items and it seems that at least some pliosaurs (Sachicasaurus with its more robust skull was maybe more adapted toward larger preys?) ate regularly things my size. Which does not appear to be usually reflected in GWS and meg.

And of course, it also depends how hungry is the animal as well as the particular personnality of the individual (as seen in GWS).

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Sept 4, 2019 9:06:26 GMT 5

It all depends what we mean by macrophagous. If I m not wrong, Foffa (or another) reports squids in the stomach contents in a specimen of the GWS-sized Liopleurodon. I doubt 5-6 m white sharks regularly prey on squids or fishrs that size, but apparently Liopleurodon could. I think, as you hint, this would have to do with maneuvrability and the shape of the rostrum, well adapted to this in Liopleurodon. Damn, I can't find the prey size range but I'm pretty sure it is in the thesis, McHenry did it by direct analogy with modern predators with a long rostrum. Yes some prey items of large white sharks are still mostly smaller but appear very rarely to be small-sized fishes and squids. With their long rostrum, pliosaurs were more able to exploit this niche than lamnids. No wonder why pliosaurs were successful for so long... Given how a 7 tonnes Kronosaurus appears to have eaten prey items of 20 kg and less, while modern GWS tend to favor rich caloric preys, I'm pretty confident that my chances of survival are a bit higher with the 15 tonnes shark, unless it becomes too curious. On the other hand, a 10-15 tonnes pliosaur would not hesitate. I think this is no myth to say that most of the apex carnivore marine reptiles, had we evolved with them, would have been extremely dangerous predators for unarmed divers, more than anything today. While I would agree that adult GWS may not look on smaller prey as their main staple and prefer comparatively larger mammalian prey (or historically in the Mediterranean, both dolphins and large tuna), we should note that they are still highly opportunistic. For instance, see below, with corresponding pictures of the squid to be found at the website www.sharkresearchcommittee.com/dist.htmAlso from the same website: Also, squid are starting to be suspected as a favorite prey for GWS when they are in the "Shark Cafe" a deep Pacific Ocean region suspected as possible mating site as well. This would make sense, as large mammalian prey or carrion would seem to be a relatively more rare opportunity in the shark cafe. Now it may very well be that the main reason the sharks are out there relates to mating, but it's quite likely they are preying on squid and other more small bodied animals than we normally think about for adult GWS. See quote below, from www.livescience.com/63614-great-white-sharks-lair.html |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Sept 4, 2019 11:04:28 GMT 5

That is good to know even if not surprising. It makes sense after all, this food source would be very useful during the periodic long journeys Of GWS. With no pinnipeds or cetaceans available in the Café, it is no wonder they rely on it.

It would be interesting though to see a statistical data of the stomach contents depending the size and region.

Note however Humboldt squids are not especially small either with adults basically the size of a small person.

There is no doubt meg was opportunist as well, and there is of course no way to know at which extend it preyed on similar prey items.

However, I doubt it was as successful to rely on smaller bodied prey items when needed.

Don't forget one of the contribution to its demise is most likely due to its main food source being unavailable.

My take is that being restricted to estuaries and river environments, usually not travelling for hunt on long distances large crocs are naturally more opportunistic than some large GWS and transient orcas.

On the other hand, it appears that large GWS become not maneuvrable enough to hunt pinnipeds, let alone small squids and fishes, and rely more and more on cetacean carcasses.

Based on this, it becomes hard to envision a 18 m Otodus preying in large part on human-sized prey items.

Various sharks researchers said, surrounding the mediatic release of The Meg movie, that such adult sharks would have had a limited a limited interest for us.

Which does not mean harmless either...

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Sept 4, 2019 14:36:02 GMT 5

As Elosha11 pointed out, great whites also eat squid. It is always difficult to be sure something is "regular" if it is a single occurrence, but assuming they are, because they would be less likely to be preserved if they weren’t, predation by Kronosaurus on sizeable plesiosaurs would be even more regular, similar to how megalodon probably focused on mysticetes. Nowadays, the great white shark is a highly generalist predator ( reported prey include other

sharks, bony fish, various odontocete cetaceans and pinnipeds, sea turtles, seabirds, cephalopods,

crustaceans, and molluscs) showing a predilection for small, fat-rich marine mammals (e.g., fur seals) (Compagno, 1984). The feeding habits of C. carcharias vary widely with ontogenetic growth Pin body size and from site to site, whereas scavenging on large mysticete carcasses is believed to contribute to a major portion of the diet of adults (Carey et al., 1982; Dicken, 2008; Fallows et al., 2013). Allowing for the obvious dimensional differences, a similar pattern could be proposed for the larger C. megalodon. According to recent works (Carrillo-Briceño et al., 2015; Landini et al., 2017), the trophic spectrum of this extinct megatooth shark may have featured a quite broad diversity of food items, i.e., bony and cartilaginous fish, marine mammals (including sirenians and euryhaline

cetaceans besides pinnipeds and salt water cetaceans), seabirds, marine reptiles (including turtles

and crocodiles), cephalopods, molluscs, crustaceans, and other invertebrates. Juveniles of C. megalodon were likely more purely piscivorous than their adult conspecifics (e.g., Landini et al., 2017); nevertheless, the target prey of adult individuals of C. megalodon may still have been the highly energetic small- to medium-sized mysticetes (e.g., cetotheriids, typically 2.5 m to 7 m long), as evoked earlier (Lambert et al., 2010). As Tricas & McCosker point out, in 9 great whites ranging from 193 to 511cm TL, not a single one had marine mammals in its stomach. The most common prey item in these individuals was the bat ray. These typically range from 9-13kg if wikipedia is to be believed. They also analyzed other specimens from the literature, bringing their sample up to 33. In those, fish was the most common prey, followed by marine mammals, with fish dominating in smaller sharks and mammals in larger ones, but even large sharks were still recorded preying on fish, and small sharks preying on mammals. Now part of this is no doubt speculation (I am not aware of any direct evidence for megalodon predation on birds, fish or invertebrates), no better than speculation on Kronosaurus prey range based on salties, however part of it is based on actual fossil evidence. Probably erraneously, but yes, adaptations enabling opportunistic feeding behaviour are usually helpful for success, see Allosaurus. However, certainly long-necked and other small-prey specialist plesiosaurs were even more successful in terms of abundance and longevity than pliosaurs. And certainly opportunistic feeding behaviour does not mean an unusual preference for small prey, or less preference for large prey (see again Allosaurus). And how large was the Liopleurodon specimen with squid in its stomach contents? We also don’t really know what size of pliosaur was responsible for the bite marks on plesiosaurs or Leedsichthys, this is a problem with all bite marks, but we cannot automatically assume the size that best fits our hypothesis. Are they really so vastly less common or is there simply a collection or reporting bias? Even a modest-sized meg is probably bigger than Kronosaurus. Collareta et al. report megalodon bite marks on the scapula of a pinniped that does not look very large, certainly not 500kg, and C. megalodon is claimed to the only known coexisting shark that could have made those bite marks. A 50 t shark is also not the same as a 5-10t pliosaur. You might not envision a 3-6 ton orca spending energy on catching salmon, but they do. The Kronosaurus specimens were also smaller than most or all adult megalodon individuals. Given megalodon focused on cetotheriids, that still doesn’t mean it wouldn’t opportunistically feed on other animals if they presented itself…e.g pinnipeds. Crocs have a dietary shift away from small fish towards larger prey during their ontogeny, much like great whites. I don’t say large crocs never feed on small fish, but do they still do so commonly? What am I missing? I am not aware of any confirmed Livyatan bite marks, let alone stomach contents. Well, that should be no obstacle if even Livyatan could even prey on things over 200 times smaller than itself, and frankly a human, even you, in the water stands little chance of escaping even the largest and most sluggish shark. Well, one Kronosaurus individual ate a 20kg turtle, so arguably less than your size. A Liopleurodon (of what size?) ate a "squid" (of what size?) Great white sharks, at least considerably overlapping in adult size range that of Liopleurodon, certainly can and do eat human-sized prey commonly. The reason Great Whites don’t eat humans is not our small size, they eat other animals our size all the time. Collareta, A., Lambert, O., Landini, W., Di Celma, C., Malinverno, E., Varas-Malca, R., Urbina, M. and Bianucci, G. 2017. Did the giant extinct shark Carcharocles megalodon target small prey? Bite marks on marine mammal remains from the late Miocene of Peru. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 469: 84–91.

Tricas, T. C., McCosker, J. E. 1984. Predatory Behaviour of the White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) with notes on its biology. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, 43: 221–234. |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Sept 4, 2019 16:58:13 GMT 5

Collareta feeding assumptions for meg are based on the GWS diet.

But this is no comparable at all with McHenry analysis who thoroughly examined the feeding mechanism in Kronosaurus, comparing its skull specifics with modern crocs as well as using stomach content.

Kronosaurus with its rostrum seems far more adapted to deal with this range of prey to me. Unlike meg with mysticetes evolution, there is indication I am aware of a direct arms race and co-evolution between Kronosaurus and the marine reptiles.

However I suspect Sachicasaurus and K. boyacensis, with more heavily built skull, to perhaps have been more macrophagous.

I would add that Collareta misses various poikts regarding the ability of large sharks to sometimes target large prey items, either by modern analogy or from the fossil record (Kallal 2010).

I need to check the source in Foffa but if I m not wrong, all the Liopleurodon specimens are in a similar ballpark so I'm assuming 5 m-ish.

I did not assume anything from bite mark, we onky know of one case (Kallal 2010) where a realistic sized range could be determined.

As for the Leedsichthys, they suggest a large tooth, suggesting a rather large pliosaur.

Even then, I never disagreed with the idea of pliosaurs able to kill prey items twice their size, I was even talking about this suggestion by McHenry long ago.

Of course, there is another issue, is the tooth mark recent or was done when the Leedsichthys was younger ?

"Are they really so vastly less common or is there simply a collection or reporting bias?"

I really doubt about any bias here, a fossil with bite marks, be it dinosaur, whale or turtles remains, always attract attention.

And again, bite marks are not always attributable to meg but mysticetes whale bones often show (despite a lack of proper publications) distinct meg teeth marks.

I don't think there is any reason to doubt that megalodon primarily targetted whales, while Kronosaurus seems more opportunistic to me thanks to its rostrum.

My question is how large were these prey items caught in GWS stomachs ? Humboldt squids are not especially small on average, we even talk about animals able to kill a diver.

Still no indication of the size of the shark here. It could be 5 m as well as 15 m.

You don't get my point.

A 500 kg sea lion is 1 % the weight of a 50 tonnes meg.

A 20 kg turtle is 0.35 % the weight of a 5.7 tonnes pliosaur.

Of course the sea lion can be smaller than 500 kg but the meg too.

So if we go by the confirmed fossil evidences, there is currently more evidence for Kronosaurus eating regularly at much smaller prey items than Otodus.

Offshore orcas, I refer since the beginning to transients. There is more evidence in macrophagy in megatooth than offshore orcas teeth.

Agreed, only there is so far no evidence of megalodon preying regularly on preys as small by comparison as the squids preyed upon by Liopleurodon or the 20 kg turtle in the stomach of the 5.7 tons Kronosaurus.

I admit this also due to the fact we don't have meg stomach contents.

Basically I agree that even a large meg would sometimes prey on pinnipeds but what size, at which rythm, at which ontogenic stages.

Even 6 m GWS tend to more rely on whale carcasses than pinnipeds. Based on this, I find it hard to envision a megalodon loses costly energy in a hunt for something extremely evasive even with valuable calories.

I have the sheer impression that it might be more regular than GWS. My understanding of the crocs ecology, is that opportunism is even more important to crocs than GWS given their more restricted habitat. From elosha mayerial, there is indication that GWS become more opportunistic toward smaller prey items when they travel.

And there is the case of the big ones, I doubr Deep Blue has interest in schools of

small squids or fishes.

However I ve heard of a suggestion that the larger ones may prey on large abyssal squids.

Sorry if I didn't write clearly, I talked about the Kronosaurus having eaten a turtle 285 times smaller than itself.

That is my point. This shows directly that any recorded pliosaur would have had interest in eating something like me.

There is less evidence for this regarding adult megatooth sharks.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Sept 4, 2019 18:11:12 GMT 5

Yes and those for Kronosaurus are based on crocodiles. Except for those cases, for both taxa, where there is direct evidence of feeding behaviour (stomach contents, bite marks). Collareta et al.’s paper is primarily a description of such direct evidence. Those points have little significance when discussing the normal prey size of an animal. Sharks (or any lone marine predator) targeting a prey item its own size or larger is exceedingly rare, and has little bearing on the typical prey size. Besides, whales that large when compared to megalodon were absent or at least very rare in the Miocene. Not all Liopleurodon specimens are the same size. This is probably the one you are referring to: www.emgs.org.uk/files/mercian_vol13on/Mercian%20Geologist%20volume%2013%201992-1995/MG13_1_1992_037_Martill_Pliosaur%20stomach%20contents%20from%20the%20Oxford%20Clay.pdfThe stomach contents of this estimated 4 m Liopleurodon contain cephalopod hooklets, some fish and an indeterminate reptile tooth. The paper also notes that bite marks (from pliosaurs or large crocodilians) on large ichthyosaurs are common in the Kimmeridge Clay, so if we are looking for the "regular" prey size, this is probably a better place to look than a single case of stomach contents. There is a case of grass phytoliths in a dinosaur coprolithe, that doesn’t mean that grass was an important part of herbivorous dinosaurs’ diets. Well, I think we’re back to tooth marks not being a reliable indicator for size, which you have yourself told me when we discussed this specimen via PM. But I would expect it to be reasonable that these cases of predation would have involved large pliosaurs, yes. If it was really Liopleurodon though, the largest known specimens would be smaller than the likely size of the Leedsichthys. And there are two cases. As we discussed, there was no mention of the tooth mark being healed. Ordinarily, I would expect such a thing to be mentioned. Yes but so do odontocetes, pinnipeds, even turtles. Well, going by the numbers, it primarily targeted plesiosaurs, but our sample size is insufficient to make solid inferences about its prey preferences or whether or not it incorporated more small prey into its diet than other large predators. The fact that in a sample of 9 great white sharks of various sizes, none had any mammals in their stomach contents should highlight how prone to variation this kind of thing is. Indeed, we see to be barely able to get clarity on the overall dietary composition of extant animals, let alone extinct ones. Humboldt squids average 20-30kg. Yes but they are pretty much identical in terms of jaw morphology. They are simply different ecotypes of orca. True, there is probably some unresolved taxonomic mess in there, but the point still stands; marine predators with morphology evidently able to exploit the niche of apex predators also feed on small prey. In the case of orcas, one might even be able to speak of different "cultures" eating different things (some mammals, some fish), but they are physically not that different. By that logic, we cannot consider these cases to be evidence of regular occurrences either. But as Martill points out, there is evidence of regular predation of pliosaurs on ichthyosaurs, and as McHenry details, there are more cases of Kronosaurus preying on other plesiosaurs than on turtles. This turtle is one data point. There’s also a data point of a turtle preyed on by megalodon. Trying to get a ratio out of this is pretty much impossible even for megalodon, and certainly pointless for Kronosaurus when we only have three recorded prey items. Well, if meg ever preyed on squid or relatively small fish, we probably wouldn’t have preserved evidence of it. There would certainly be a preservational bias for large tooth marks on large bones, small bones by their very nature couldn’t preserve such tooth marks. So if meg ever decided to snack on a humboldt squid, we would never know about it. Yes, but they scavenge them, that is an entirely different situation. But the diet of 6m+ great whites certainly needs some work. Due to the rarity of these individuals, this is pretty much unstudied. As is the diet of 6m+ crocodiles I might add. Even a 4m cetothere or 3m kentriodontid would be very evasive for a 15m shark, but obviously it could catch them. What is a "sheer impression" supposed to help in this regard? Crocs don’t have a more restricted habitat, if anything they have a less restricted habitat–although that would argue in favour of opportunism. But unlike crocodiles pliosaurs were not semi-aquatic and probably fully marine. Yes, so? Logically, the same could hold true for pliosaurs, we don’t know the circumstances for every documented case of stomach contents. This means some pliosaurs would have had interest. Some orcas have interest in salmon. Others don’t. Some 5m great whites are apparently content with eating fish, others aren’t. At least one megalodon of whatever size (which we can probably expect to likely have been bigger than the small Kronosaurus that ate the turtle) ate a relatively modest-sized (scapula lenght c. 20cm) seal. |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Sept 5, 2019 22:10:01 GMT 5

Other than some details I think could be tweaked, I mostly agree with the last response I got from theropod.

The interesting point is that both large pliosaurs and megatooth sharks show capabilities to have tackled large prey items.

Somehow, even though the big pliosaurs are smaller than Livyatan and Carcharocles, they had the opportunity to have targetted larger animals, as the Neogene superpredators had very few animals matching their size for most of their existence (though there is reportedly a huge cetotherid skull from the Ocucaje that could indicate a fin whale-sized animal.

However, I still think, simply based on their modern counterparts, that both adults Livyatan and Carcharocles would have been less dangerous for a diver than the large or medium size pliosaurs.

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Sept 5, 2019 22:59:04 GMT 5

Grey, to reference a couple of your questions above. With respect to the Huboldt squid I referenced, the picture of it is copyrighted and cannot be posted here without the website's permission. But it can be viewed here. www.sharkresearchcommittee.com/dist.htm Even with the shark apparently biting off the tentacles before ingesting, it seems a fairly large specimen. My guess is it would at the high end of the 20-30 kg average theropod referenced, but no way to confirm that. At a minimum, it's a quite long squid. Maybe about as long a human, if the 18 inches of cutoff tentacles were added. You also said: As theropod mentioned, we really don't know the feeding habit of very large GWS. It should be noted that when Deep Blue was first cited and tagged with an underwater camera, the researchers indicated her behavior and dive patterns seemed very indicative of her hunting for elephant seals at Guadalupe Island. Apache, a 5.5+ meter male GWS, has been seen predating on elephant seals, either at Guadalupe or Farallones, can't recall now. Also, the 17.7 foot 4100+ specimen also referenced at www.sharkresearchcommittee.com/dist.htm had two pinnipeds in its stomach but it also clearly was feeding on bat rays. Also, many very large GWS in Asia and Mediterranean have been found with numerous dolphin prey. I think whether juvenile, average or very large adults, GWS are always going to be highly opportunistic and much less specialized than we might presume. I also think very large sharks are probably much more active and explosive than you might believe -- when they need to be. As evidenced by the fact that many large specimens are shown to have predated on large and/or fast prey items. Yes, they do scavenge and gorge on whale carcasses when they can get them, but the ocean is way too big for them to rely on that exclusively. I think GWS are very active predators at all stages of their lives.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Sept 6, 2019 0:07:21 GMT 5

Agreed.

I think a primarily scavenging ecology for a large marine predator might even be more problematic than it is for a terrestrial one (where it’s not viable either).

Exploitable carcasses are rare, and there is heavy competition for the ones that do exist. Carcasses tend to sink to the sea floor at some point, so for most pelagic predators that puts the food out of reach comparatively quickly. And since large marine predators often prey on relatively small animals that they eat in their entirety (seals, penguins, fish) and the marine equivalent of large herbivores (i.e. mysticetes) are really only preyed on occasionally (by a single species, in the extant world), there’s probably less carrion to go around in the first place. Compare that to big terrestrial predators, almost all of which will inevitably leave partly eaten carcasses of large animals in their wake. All this is very bad for pelagic scavengers, even if the occasional carcass is very large, because it makes the presence of carcasses less predictable.

Even in terrestrial settings, scavenging is not a dependable food source for any large predator that cannot fly, and I wouldn’t imagine that being primarily a scavenger is a viable ecology for a large pelagic predator like a great white shark either.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Sept 17, 2019 18:26:12 GMT 5

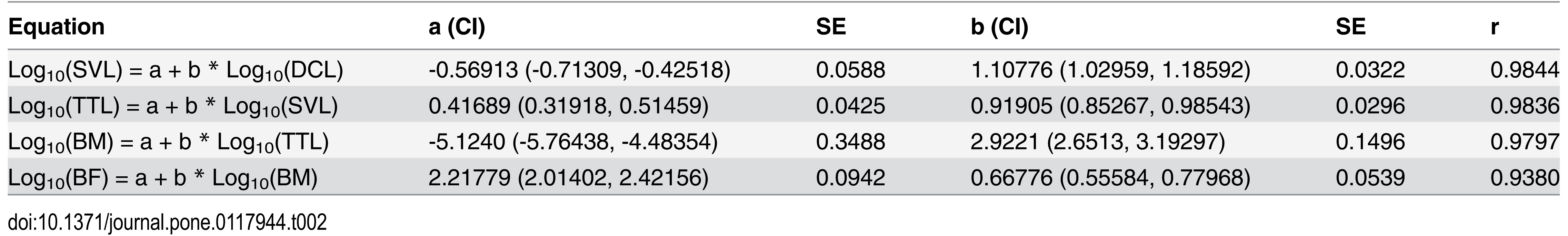

There’s a problem the regression Aureliano et al.’s used for their bite force estimates, which affects the estimates I have posted here as well. They used the mean values for both body mass and bite force values. I’ve just re-run their regression with the dataset they provide and can confirm there are indeed the values they used, the same as the "mean" values reported by Erickson et al.: Call: lm(formula = log10(crocbf$bf) ~ log10(crocbf$bm))

(Intercept)=2.2178

log10(crocbf$bm)=0.6678 Compare:  But this doesn’t work, mass, length and force all scale with different exponents, so just taking a normal mean produces a vast incongruency: If you have three geometrically similar crocodiles, with lengths of 1, 3 and 6 m, and a 6 m croc weighs 1000 kg and has a bite force of 10 kN, then the mean length is obviously 3 m, the mean mass is 377 kg, and the mean bite force is 4.3 kN, but the isometrically scaled 3 m croc would actually weigh just 125 kg and have a bite force of only 2.5 kN. It’s easy to miss, and I used to make this error myself (with the very same study, actually), but that’s probably why the results are lower (bite force scaling to the 2nd power gets underestimated relative to body mass scaling to the 3rd power) compared to the regressions used by Erickson et al. So in short, while it’s the correct approach to log-transform the data (especially for extrapolations) there’s another mathematical problem they didn’t account for. |

|