|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Mar 10, 2020 7:41:48 GMT 5

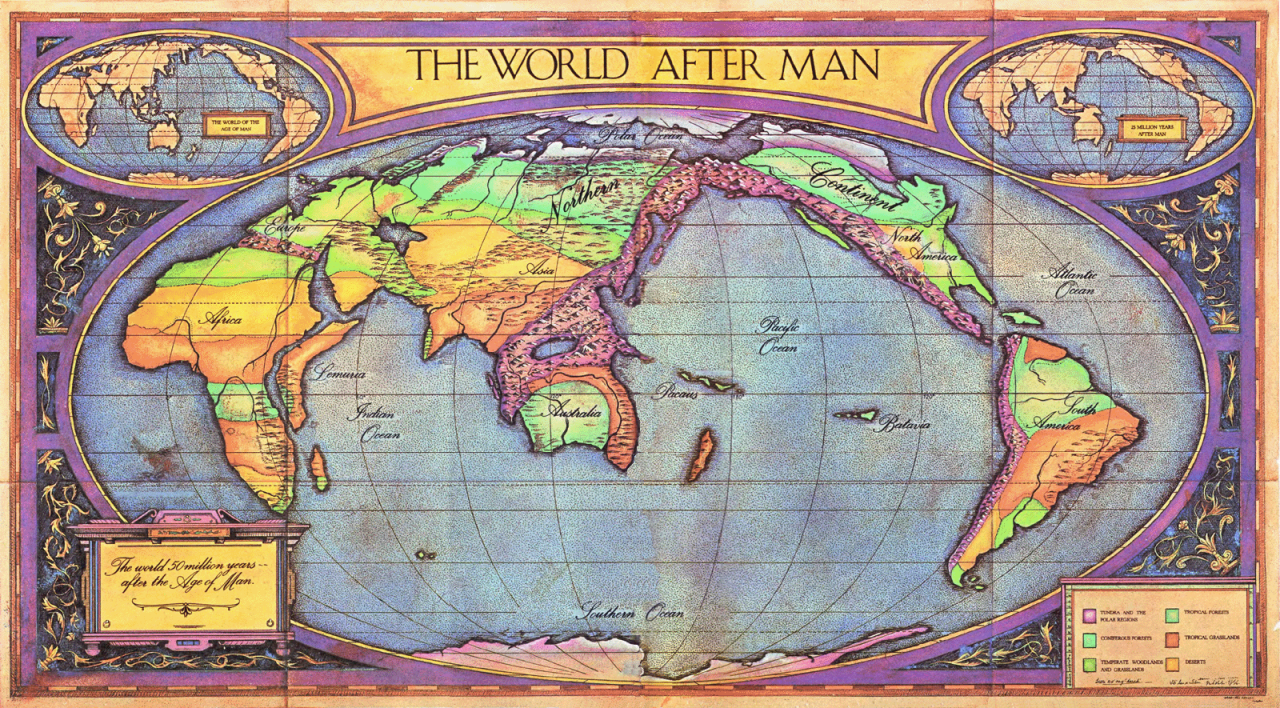

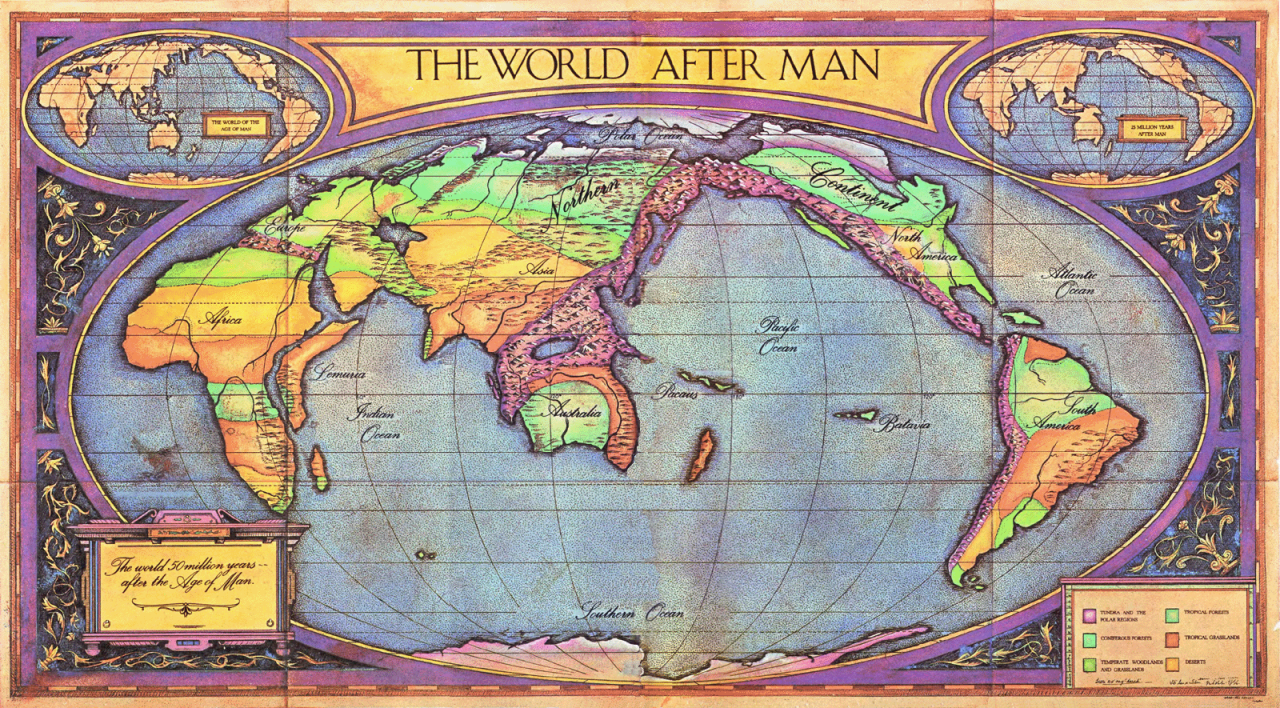

Long before The Future is Wild, there was After Man: A Zoology of the Future, written by Dougal Dixon in 1981 (incidentally, this man went on to work on TFIW). Although there were speculative evolution works before even it, After Man is widely accredited as the book that really kicked off the genre. On the Internet I've seen Dixon called the "father of speculative evolution" or "speculative evolution's king", titles I think he's probably earned. After Man has a similar premise to TFIW; humans have gone extinct sometime in the modern era and it explores what animal life has evolved to look like millions of years onward. Unlike TFIW, it only looks at one point in time, 50 million CE, but it explores that given time's various ecosystems across the globe. Earth's familiar biomes are still around (so there are still temperate forests, hot and cold deserts, grasslands, etc.), but the geography has, of course, changed substantially. Mammals and birds are still the "dominant" vertebrates. Like TFIW, and as he explicitly states in his own introduction, Dixon isn't trying to make a firm prediction on what will evolve in the future, but rather an exploration of possibilities. So do not mistake this for him saying "oh yeah, this will definitely happen". Nevertheless, this doesn't mean we can't examine some of the hypothesized species and decided whether or not they'd be feasible to evolve. Hence, this thread. A few things to keep in mind: I'm not sure I can review this in the same way I reviewed TFIW. TFIW had a few creatures in each episode, but getting them all in a review for one episode was already a bit of a task. Each biome Dixon explores in After Man shows us much more than just three, four, or five organisms. So I'm thinking I have one post dedicated to a biome, which I'll continually edit to include more creatures until that biome is done. I will tag those who are interested to check the new creatures added (and this won't be hard, since Dixon divides organisms within one biome into which particular space/niche they occupy; subchapters, if you will). If you want to be tagged for these notifications, please indicate so down below. Alternatively, if you have a better idea of how I should do this, please let me know. Edit: I forgot to mention, I will use the same plausibility ranking that I used for TFIW. It should work just as well for After Man. I'll get started in the very next post (as much as it kind of disappoints me I'm not starting it in this one). But for now, enjoy this illustration of Dixon's Earth 50 million years in the future.  Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->Oh, and uh, welcome to the future.  From Scientific American-> (though I cannot see the image at present). |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Mar 11, 2020 6:38:26 GMT 5

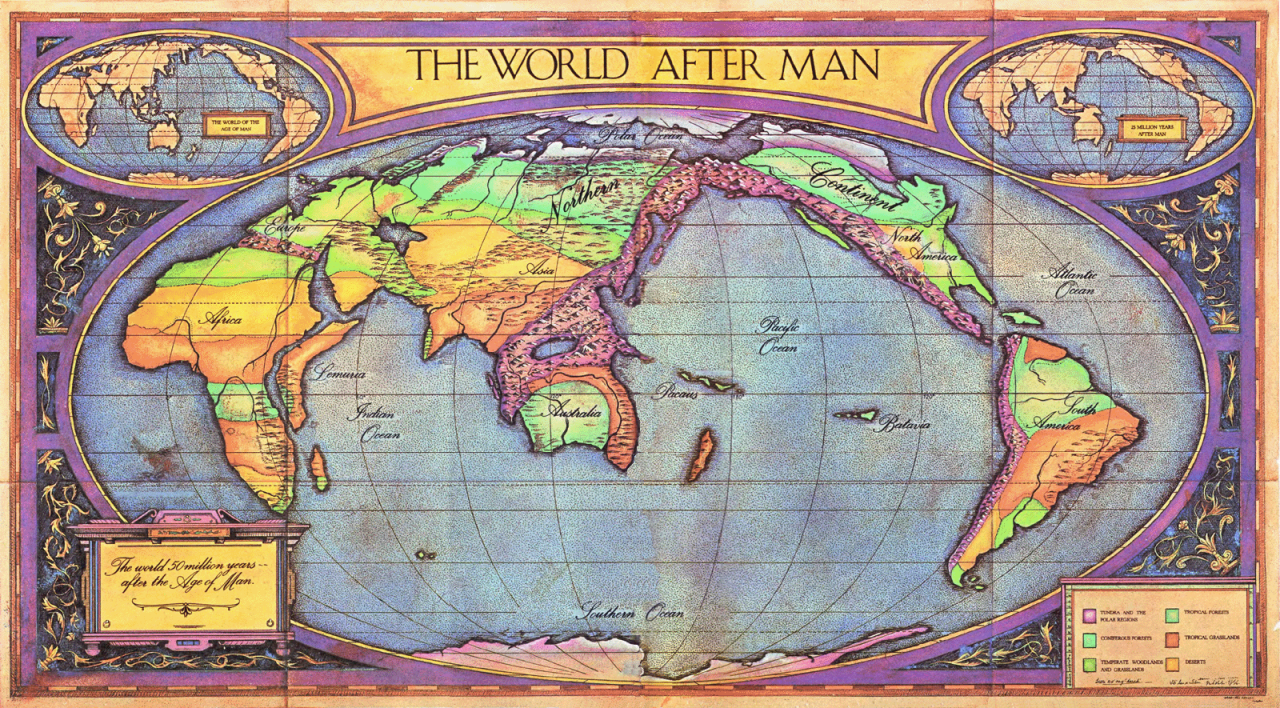

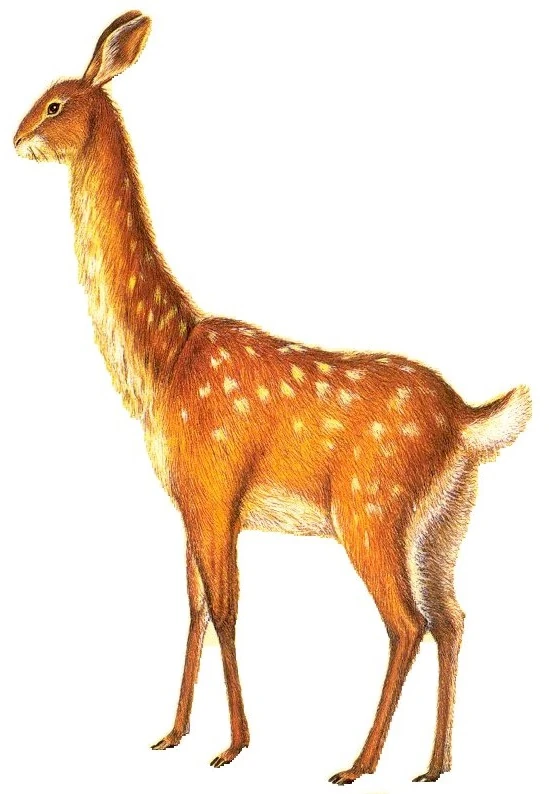

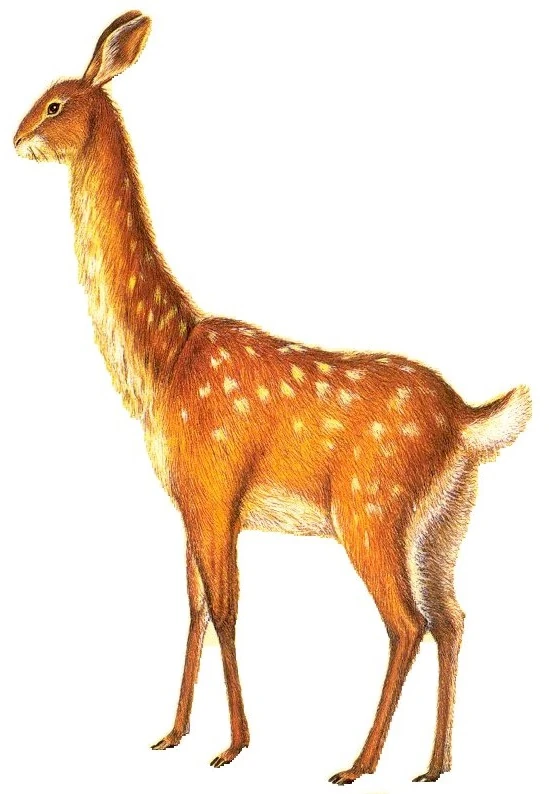

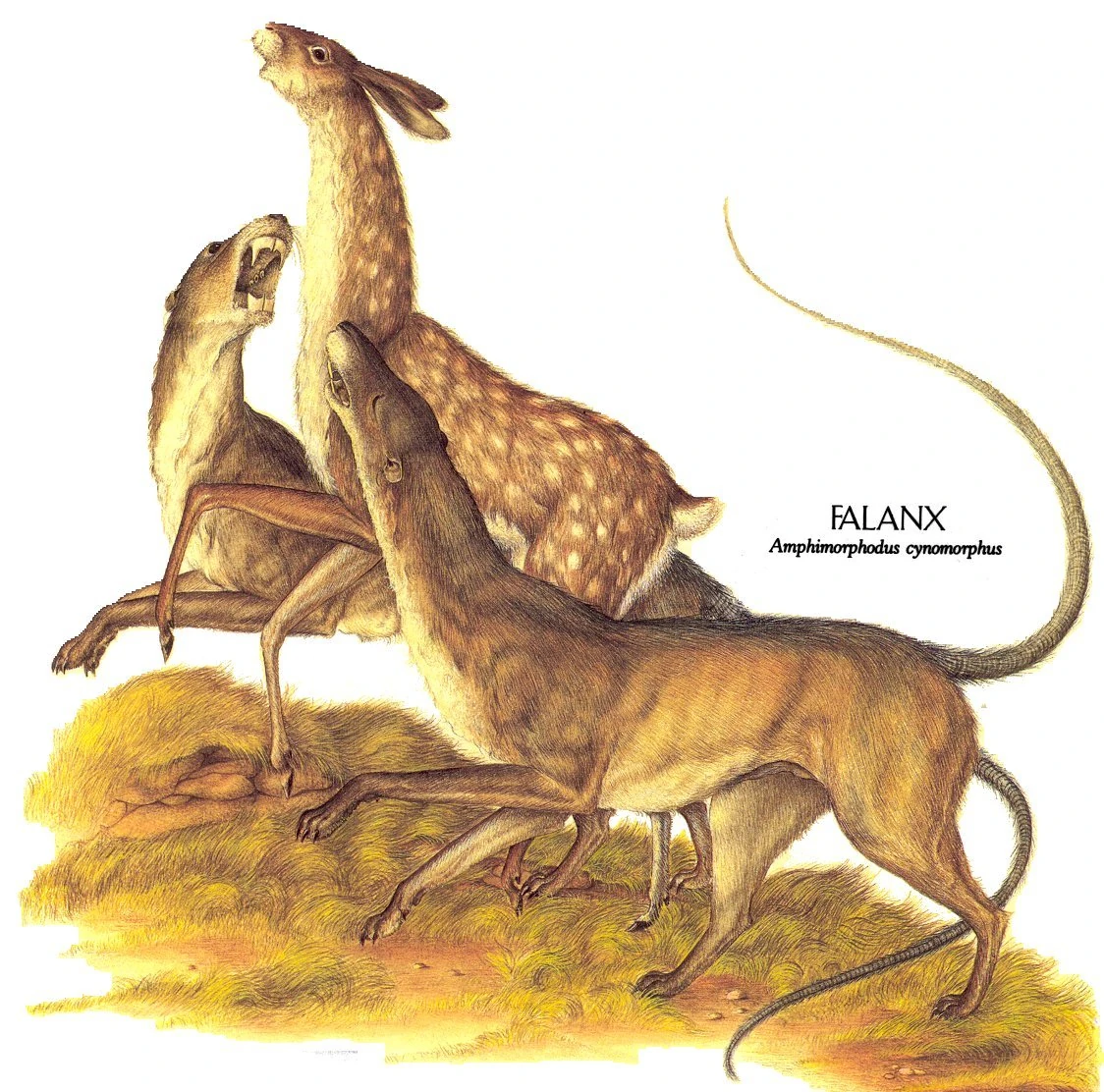

For the record, I'm still unsure of how I should structure this post series. Temperate Woodlands and GrasslandsRabbucks:  The common rabbuck ( Ungulagus silvicultrix). Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->. Click here-> for the arctic rabbuck ( U. hirsutus). Click here-> for the desert rabbuck ( U. flavus). Click here-> for the mountain rabbuck ( U. scandens). Domesticated ungulates have gone extinct after humans did, being too dependent on them for survival. Deer in the temperate latitudes have gone extinct due to anthropogenic influences (most notably habitat loss). As a result, rabbits have evolved to take the ungulate niche (they did this in the tropical grasslands too, more on that in a future post). Most notably they became larger, but at first they still hopped like their ancestors, resulting in the hopping rabbucks ( Magrolagus spp.). Several hopping rabbuck species still exist, but they are no longer the most common type. Around 10 million years after the Anthropocene, running rabbucks began to evolve to better deal with the more confined spaces of forest habitats (which the ancestral hopping gait was not the most effective in). These have actually evolved an ungulate-like limb morphology, with digits II and III becoming unguligrade with hooves strong enough to bear the animal’s weight. Digits I and IV have atrophied. They have largely replaced their hopping relatives as the dominant rabbuck group. Rabbucks have proved to be successful, evolving into a variety of habitats (as I’ve shown above; there are more rabbuck species in subsequent biomes). These creatures have garnered criticism in that people have found it unlikely that a sufficient number of ungulates would go extinct and let something like rabbucks evolve. Looking at cervids (particularly North American ones), it looks like there are some that are doing quite well (Least Concern) today, although I don’t know if that’s changed since the 1980s when this book was written. It could be possible that some ungulates (even if we limit ourselves to just cervids) can go extinct, but at the same time I’m sure that other ungulates will simply take those vacant niches. Now, to be fair, this is 50 million years after our time. That’s three quarters of the entire Cenozoic. Is it possible that some new environmental development could occur, particularly one detrimental to ungulates but beneficial for new competitors? I’d say so, but such an event is not elaborated upon in this book because that’s not what kills off some of the ungulates for rabbucks to evolve. Could the extinction of some ungulates open a window of opportunity for rabbits to successfully evolve into ungulate analogues and maybe even outcompete them? Maaayybeee…….? But I wouldn’t count on it. Final verdict: intermediate (it’s not an implausible concept) to implausible (I don’t quite buy the explanation for what let them evolve). Predator rats:  Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->. A wolf-like predator rat species (named in the image). Click here-> to see the rapide ( Amphimorphodus longipes), a cheetah-like form; the ravene ( Vulpemys ferox), a wild cat-like form; the janiset ( Viverinus brevipes), a stoat-like form; and the species depicted above, respectively. The carnivorans are no longer the dominant predatory mammals on Earth, having largely died out and relegated to an assortment of specialized niches across the globe. Dixon writes them off as just too sensitive to changes in their environment and prey populations, but I’m sure there’s an implication that humans played their part in the fall of the carnivorans. So who evolves to take their place? Rats…apparently. As the carnivorans reigned, the rats have acquired an increasing taste for meat and animal waste. “ The spread of man to all parts of the world encouraged their proliferation and after man’s demise they continued to flourish in the refuse created by the disruption and decay of human civilization”. Predator rats have evolved a variety of postcranial adaptations for different lifestyles and hunting strategies, but the one unanimous change from their ancestors was in their jaw apparatus. The gnawing incisors have developed canine-like points from their lateral corners, equipped with blades to cut into and grip prey; the incisors basically now do double duty as carnivoran incisors and canines. The diastema between the incisors and the premolars/molars became smaller (although it’s definitely still there) and the molars became shearing teeth to fulfill the same function as carnassial teeth. Lastly, the rotary range of motion went from a grinding action to an orthal (up and down) one. The falanx (the species depicted above) is the common rabbuck’s most important predator, hunting in small packs and wearing them down into exhaustion. It is also apparently the largest member of the predator rat family. One criticism I remember seeing for the predator rats is that the continually growing incisors of rats would not let them develop into canine-like points that could last indefinitely. I don’t think I agree with this: Thylacosmilus had continually growing saber teeth that still managed to stay pointed and dagger-like in shape, so I don’t see why a rodent’s incisors couldn’t. I wonder if they could retain their gnawing incisors for predatory purposes. After all, there are carnivorous rodents today that seem to retain this incisor morphology; look no further than the grasshopper mouse. But then again, this might not be a good comparison: grasshopper mice hunt insects, spiders, centipedes, scorpions, snakes, and even other mice, but predator rats have to hunt rabbucks. Pointed teeth might be necessary to evolve to kill this larger prey. This, however, all assumes that the carnivorans and other potential competitors are out of the picture for their evolution. While I’m sure some carnivorans could very well go extinct, as with ungulates, I also have a gut feeling that other carnivorans could take their place. That said, at the risk of sounding stupid, I don’t think it’s entirely impossible that within 50 million years, something (most likely environmental in nature) could happen that could force carnivorans into evolutionary periphery. I mean, if it happened to the arctocyonids, mesonychids, hyaenodontids, oxyaenids, and entelodonts before, I don’t see why it couldn’t happen to carnivorans eventually. Final verdict: intermediate to implausible. |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Mar 11, 2020 16:58:26 GMT 5

I see I'm not attracting as much interest for this as with TFIW. So I'm thinking I'll only do this if people are actually interested in it. I'll make maybe a couple new posts with the next creatures of the temperate woodlands and grasslands for notifications (since no one has indicated an interest in being tagged). If people are not interested by then, I'll pull the plug.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Mar 11, 2020 17:31:01 GMT 5

Well, I was the main commentator for TFIW and you have the misfortune that I have just found a full-time job recently. I might read the above post later.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Mar 11, 2020 19:02:50 GMT 5

Ah, gotcha. Good luck with your job first and foremost, but also hoping you find interest here too.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Mar 16, 2020 7:30:50 GMT 5

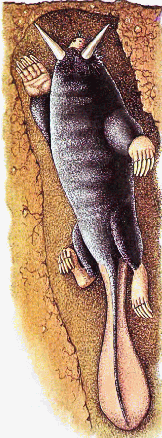

Creatures of the undergrowthTestadon (Armatechinos impenetrabilis):  Taken from Flickr->A hedgehog descendant. It is 30 cm long. The spines have evolved into hinged armored plates; when the testadon curls up, the plates basically form into an armored ball that is impenetrable to predators, even to the predator rats. I guess? I don’t think anything immediately jumps out as implausible. Some reworking would need to be done for the spines to evolve into segmented plates, but I don’t think it’s “out there”. Seems more plausible than a rodent with absolutely no precedent for armor evolving it. Final verdict: plausible. Tusked mole (Scalprodens talpiforme):  Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->Came “ somewhere between the old order of insectivorous animals and the newer carnivorous ones”, so I’m guessing it evolved from “insectivores” (note: “Insectivora” used to be an old wastebasket taxon, does not form an actual clade, and is now outdated). It has a streamlined shape, velvety fur, and spade-like feet, just like a mole. Eeeexcept it also has two tusks protruding forward from its face and a paddle-like tail. It digs through the sole by moving its feet in a rolling motion, while the tusks ream out the soil in the way. The loose soil pushed out by the tusks is then pushed back by the feet and compacted into the walls of the tunnel by the tail. It preys on invertebrates like worms, but also mice, voles, and lizards via ambush. This creature will wait underground, with only the very surface of the soil separating it and the outside world. Its tail is tucked underneath it. When it hears prey approaching, it uses its spring like a lever to burst out of the soil and grab its victim with its teeth (click here-> for a visual).  link-> link->I don’t have a problem with a burrowing animal using its teeth to dig with (*cough* Palaeocastor *cough*). But I agree with the person who made the tongue-in-cheek drawing above that having two tusks protruding forward from your face, especially when they don’t even run perfectly parallel (running somewhat laterally), sounds more like a detriment to moving through soil, especially when the soil can be very rocky. Maybe having one tusk pointing straight forward like a narwhal would be better, but even then I don’t think that would work very well, or at least not as well as clawing or scraping away at the dirt using claws or non-tusk teeth. Final verdict: implausible (particularly the design, not the niche, of course). Oakleaf toad (Grima frondiforme):  Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->This toad has a fleshy outgrowth on its dorsal surface (extending on its head and even its legs) that looks like a fallen leaf. The purpose of this is to provide camouflage when hiding in fallen leaves, both for hunting and avoiding predation itself. As it hides in the litter, it sticks out its long, pink tongue and wriggles it so that it resembles a live earthworm. Prey animals that come close thinking they’ve found a meal are instead suddenly apprehended by the toad’s powerful jaws. Its prey can include small mammals, as an illustration in the book-> shows. Its only real enemy is the predator rat (though, Dixon doesn’t make it clear which species; the falanx maybe?), with whom it has an interesting relationship with. You see, there is a species of fluke that lives its juvenile life in the bloodstream of the toad, and its adult life in the bloodstream of the predator rat. When the fluke begins its process into becoming an adult, it releases a dye that turns the fleshy outgrowth on the toad’s back into a bright green color (it seems that the default color is brown). Since this happens in the winter, the toad becomes all too easy to spot and is eaten by predator rats. This transfers the fluke from the bloodstream of the toad to that of the predator rat, where it matures and reproduces. When the predator rat defecates, the fluke’s eggs come out with the feces. Beetles eat the feces (and inadvertently the fluke eggs), and the beetles themselves are eaten by the toad. Luckily for the toads, they become sexually mature after 18 months, while the fluke needs at least 3 years to grow in the toad’s body before it’s ready to parasitize the predator rats. As such, all toads have the chance to reproduce before the fluke’s dye sends them to their doom. There are already toads that camouflage in leaf litter, and they have some damn convincing skin patterns for it. I guess it doesn’t sound too unlikely that they could take this even further as in the oakleaf toad. It has an interesting and weird relationship with the predator rats and flukes, but I don’t think that’s completely impossible either. Final verdict: plausible.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Mar 16, 2020 20:31:20 GMT 5

That's an awesome fluke. It also feels realistic, given the existence of a real life precedent whose name I forgot.

This is surely an interesting book. Seems like TFIW without the implicit anti-mammal/vertebrate bias.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Mar 20, 2020 22:19:20 GMT 5

Just a crazy thought I've had:

Would it be possible for TFIW and After Man to exist in the same universe? The mammals 50 million years in the future would be temporally far removed enough from those five million years in the future to erase obvious connections. Likewise, whatever extinction wiped out mammals in TFIW basically leveled the playing field, meaning that anything goes. The answer is probably "no", but stil a funny thought.

BTW, I think there is an "after" too many in the title.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Mar 25, 2020 20:53:56 GMT 5

Just a crazy thought I've had: Would it be possible for TFIW and After Man to exist in the same universe? The mammals 50 million years in the future would be temporally far removed enough from those five million years in the future to erase obvious connections. Likewise, whatever extinction wiped out mammals in TFIW basically leveled the playing field, meaning that anything goes. The answer is probably "no", but stil a funny thought. BTW, I think there is an "after" too many in the title. I remember trying to reconcile the two worlds before. The biggest thing that jumps out to me now, though, is After Man still has polar ice caps (given their extent, I'd say it's in an interglacial period), hence the world is still technically in an ice age (just like how we are today, just in an interglacial period). In TFIW, the ice age ends around 5 million years into the future, so the events we see in the 5 million CE episodes aren't too terribly long before the ice age ends. It was hothouse Earth, or at least a trend towards a hothouse Earth, for the next 95 million years. So my guess is 50 million CE in TFIW had no polar ice caps, and probably couldn't be in the same world as After Man. Maybe there could have been a temporary (and I mean very temporary) return to glacial conditions at some point between those 95 million years, but that seems less likely. |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Apr 24, 2020 8:58:12 GMT 5

I've been busy lately, which is why I haven't been able to get to this in a literal month. I promised myself I would post something here today (since I was less busy today), but forgot. I'll try to remind myself tomorrow.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Apr 25, 2020 6:39:33 GMT 5

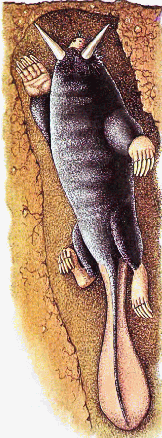

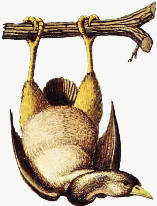

The Tree DwellersChirit (Tendesciurus rufus):  From the Speculative Evolution wiki->A small herbivorous mammal immediately descended from a tree-burrowing rodent of the northern coniferous forests, and distantly descended from the grey squirrel. Its immediate ancestor had enormous gnawing incisors to bore through trees and nest in them in order to escape harsh winters. But as it moved down south, it no longer needed to do this, and so its teeth have atrophied in size to more closely resemble its distant ancestor's. It has short hindlimbs and feet with hard, scaly undersides and strong claws for gripping. The ventral surface of the tail also has this hard scaly surface. This creates a three-point anchor that secures the chirit onto a tree as it reaches out to grab food with its extremely sinuous body. It actually moves more like a caterpillar with that sinuous torso. The chirit is found in dense thickets, and its only real predators are birds of prey, and even then only when it's on top of trees. This is one of those "hard to believe but maybe not completely out there" creatures. My first question would be "Why not just evolve to be like a squirrel?" in lieu of evolving this bauplan with a new mode of locomotion and feeding. Maybe not impossible, but sort of on the less likely side. Final verdict: plausible to slightly implausible (broadly)?Tree drummer (Probosciuncus spp.) From the Speculative Evolution wiki->An insectivorous shrew-like mammal, which I think was descended from a member of the now outdated group called the "insectivores". The undersides of its feet are covered in bristles meant to sense grubs moving inside tree bark. Once it senses a grub, it bores through the wood using its chisel-like teeth, grabs the grub with its gristly proboscis, and eating it. Sometimes the grub gets impaled on its teeth, and so it needs to carefully remove it before eating it. This thing's "chisel-like" teeth look more like elephant tusks if you ask me (in fact, this thing reminds me of an elephant in appearance). I'd make them look less like ice picks and more like actual chisel teeth if that's the route Dixon wants to go. I'm also not entirely sure if bristles on the feet are the best call when picking up vibrations from something that's under relatively thick wood, but I could be entirely wrong on that. If not, then I'd either go with really sensitive skin on the feet and/or large ears (like what an aye-aye has) instead. Other than that, plausible. Final verdict: plausible to somewhat implausible (broadly).Tree goose (or hanging bird: Pendavis bidactylus) From the Speculative Evolution wiki->An arboreal bird. Its feet have been reduced to having only two directly opposed, permanently curving toes to grip tree branches, letting it grip branches without any effort. Because of its weight, it's become easier to roost upside down than upright, and so it spends a lot of time roosting in this position. Okay, so it's basically an upside-down roosting bird. The permanently curving toes are a little weird but...maybe not that out there (and he does provide an IMO reasonable explanation for why this feature evolved). Only issue is why get rid of the other two toes? If anything, retaining more of them should give it a more solid grip. Final verdict: plausible overall.

|

|

smedz

Junior Member

Posts: 195

|

Post by smedz on Apr 25, 2020 19:11:27 GMT 5

I see I'm not attracting as much interest for this as with TFIW. So I'm thinking I'll only do this if people are actually interested in it. I'll make maybe a couple new posts with the next creatures of the temperate woodlands and grasslands for notifications (since no one has indicated an interest in being tagged). If people are not interested by then, I'll pull the plug. I'm here for ya. |

|

|

|

Post by 6f5e4d on Apr 25, 2020 20:56:29 GMT 5

Also reading up on these. They look good too.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 13, 2021 21:25:19 GMT 5

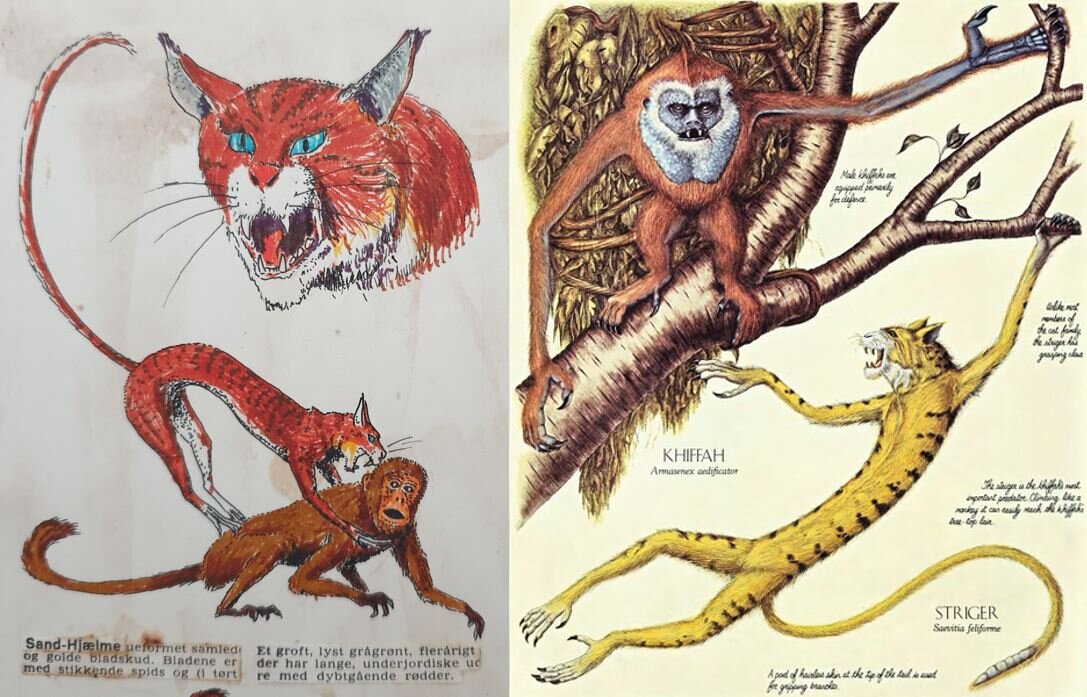

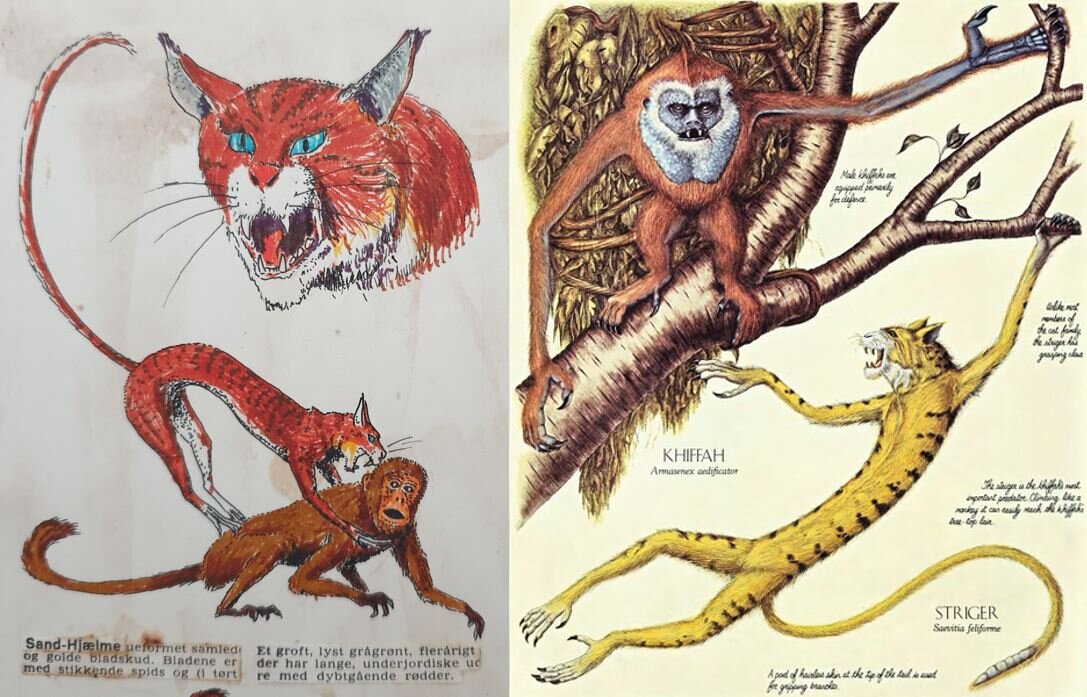

I realize that I haven't updated this thread in a while. I haven't forgotten about it, it's just that I've needed/wanted to do other things. I think instead of tackling one whole ecosystem, I'll give my thoughts on one species at a time. Also, I could have sworn I had a full PDF of After Man to look at, but for some reason I can't find it anymore. Right now, however, there's one creature I really wanted to comment on. Striger: Left is Dougal Dixon's original depiction of the striger in his pitch. Right is the image that appeared in the final product in 1981 (done by Diz Wallis). Image source->. Basically, the striger ( Saevitia feliforme) is a cat that evolved a monkey-like body plan to become a specialized predator of primates and other arboreal animals. The original book notes that the striger's evolution actually caused the extinction of many specialized arboreal animals, and forced the evolution of further defenses in those that remained. One thing I pointed out in my TFIW thread is the apparent need for clavicles to brachiate, as these support the scapulae and the muscles required for flexible but powerful arm movements needed for brachiation. Felids have very reduced, vestigial clavicles ( here's an X-ray image of a cat showing the clavicles), so one evolving a bauplan specialized for brachiating to catch primates is implausible. Also, I don't see why the evolution of a predator with the bauplan of a monkey would necessarily drive tons of arboreal species into extinction. Arboreal mammals (e.g. primates and sloths) can and have coexisted with predators that have easy access to the treetops. I am, of course, talking about certain eagle species (e.g. the Philippine eagle, crowned eagle, harpy eagle, etc.). Predators that can fly. Although they do have to maneuver through trees, I still consider flying to be a much easier way to access arboreal prey than actually having to traverse through trees via brachiation. And yet while these raptors are certainly formidable predators, they obviously haven't driven their arboreal prey base to extinction. I fail to see why this monkey-cat would. Final verdict: implausible. |

|

|

|

Post by Supercommunist on Feb 16, 2021 3:47:25 GMT 5

^Yeah I can't think of a predator flat out adopting the same build as its primary prey.

|

|