|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 6, 2013 18:24:19 GMT 5

You mean the range at which the adductor force would be applied effectively would be narrow? Then I know what you mean. Of course, if the jaw is opened for 90° the adductor muscles cannot function very efficiently since much of their force would be directed anteriorly. But that doesn't mean it couldn't attain such a gape. The gape is limited by how much anteriorly the muscles insert and how broad and voluminous they are, not? Since we don't know the musculature or even mandible, how can we say how flexible the craniomandibular articulation was? from this it seems to just speak of the back of the toothrow, so a backwards-shifted end of the toothrow seems to be an option. It seems animals with large gapes always utilise postcranial forces (eg. impact feeding in sharks, slashing bites) anyway to drive the teeth into the prey on contact when the jaw is gaping, so "functional gape" is not always the same as the gape size at which the jaw musculature can function efficiently. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 6, 2013 18:28:34 GMT 5

speaking of this, what about the gape of Spinosaurs?

|

|

|

|

Post by coherentsheaf on Jul 6, 2013 19:05:54 GMT 5

You mean the range at which the adductor force would be applied effectively would be narrow? Yes. |

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jul 6, 2013 19:45:34 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 6, 2013 20:16:40 GMT 5

coherentsheaf: Ok, I know what you mean then. It never was about the gape at which the adductor muscles would be effective, at least not what I usually talk about when discussing the issue. Imo "functional gape" isn't a very good term to refer to angles at which mandible adduction produces strong forces, since that's only part of the bite. What I don't get is what the difference between it and the others could be if that was meant, since jaw closers will never function efficiently at a big gape angle, and the mandible or even jaw joint are not known for Carcharodontosaurus. creature386: Damn, I whish there was still access to JSTOR! Have you downloaded that paper? Sounds very logical and is not surprising, a stiffened mandible to transmit force more effectively while biting down with lots of force (a less kinetic cranium and mandible is a common adaption to crushing). Similar to the fused nasals. The "shock-absorber" on the other hand was further posterolateral, in regions where the skull was broader (postorbital/jugal and maxilaa/jugal sutures).

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jul 6, 2013 20:25:16 GMT 5

creature386: Damn, I whish there was still access to JSTOR! have you downloaded that paper? Sounds logical, a stiffened mandible to transmit force more effectively using it. Similar to the fused nasals. And I guess the "shock-absorber" was further posterolateral. No, I haven't downloaded it (I rarely do so), I just remembered the comment which I wrote in a time, when we all had access. carnivoraforum.com/single/?p=8452653&t=9793275 |

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on Dec 12, 2013 8:25:42 GMT 5

Theropod talked about that earlier. It is really an interesting subject. The main problem that I have with this claim is that spinosaurus did not kill with powerful biting, but would rather have killed with very precise biting utilizing the ability of its conical teeth to pierce deeply WITHOUT MUCH RELIANCE ON POWERFUL BITING. Its snout was resistant, but the strength attributed to it was designed for gripping as opposed to being used for exerting massive amounts of force; that is what made them strong. The possession of a strong snout in spinosaurus is rather attributed to its ability to resist the forces exerted by large fish, and it was actually very well designed to do this as evidenced by its robust rostrum and spike-like dentition designed for gripping such large animals. Spinosaurus did not possess a weak snout, even if it was not designed for crushing or killing!

To think that spinosaurus at a weak snout is demonstrably wrong; but it was not designed for crushing or killing. I have been pointed out to before that torsional resistance is different from gripping resistance, in which case spinosaurus fundamentally lacks not only due to its lack of an exceptionally wide snout but also its possession of a snout that was not flattened and was instead quite well-rounded in terms of dimensions (its depth and width was quite similar). Such an exceptionally powerful bite as Cau is proposing is unlikely as I have pointed out. I say again, what makes its snout strong is the robusticity and resistance factors attributed to it. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Dec 12, 2013 17:18:08 GMT 5

Godzillasaurus: We don't actually have a cross-section or similar evidence of an allosauroid rostrum, so that's again entirely hypothetical. "Fenestrate" doesn't equal "thin-walled". The same applies to what you say about Spinosaurus' jaws. You at the same time deny it had a powerful bite and teeth suited for killing, but claim it killed by shaking (which requires a far more powerful bite, a much greater amount of force and a much much greater stress resistance). I have already highlighted Spinosaurus' had marked difference to crocodilians. 1.)The teeth are longer, generally larger and the longest ones are concentrated just posterior to the upper-toothrow-diastema. 2.)Their evolutionary shape-shifts do not make the slightest sense if they were used for killing via ripping. 3.)The rostrum would be expected to be broadened and flattened to resist extreme lateral stresses if it killed by lateral shakes. 4.)The same applies to the mandible. 5.)Spinosaurus, due to restrictions imposed by its size, partially terrestrial ecology and morphology, could not perform the kind of manauevers crocodiles often utilise. regarding 1.: This suggests emphasis on puncturing perpendicularly, instead of shaking or pulling laterally or posteriorly. Animals with increased emphasis on the latter two have teeth that are either short pegs (like crocodilians), large and tremendously robust and bear carinae (tyrannosauroids) or that are intermediate in lenght, flat and very sharp (carnosaurs, Varanids). regarding 2.: The more plesiomorphic state seen in baryonychines would be more advantageous since the teeth retain carinae and are shorter and for a more saw-like structure. They would be easier to use in this regard since they'd encounter less resistance. regarding 3.: Instead, it is narrow but relatively deep compared to crocodiles, which rather suggests perpendicular biting. crocodiles have teeth with a morphology made for gripping (because among their main purposes is gripping and drowning). For dismembering they make up for the difficulties with a massive bite force and tremendous application of external force. Spinosaurus does not have such adaptions, but would require them to rip something in a crocodile-like fashion. regarding 4.: Crocodiles have rather shallow but wide mandibles, the opposite is the case in Spinosaurus. Regarding Cuff & Rayfield's results, it can be argued there are potential sources of error affecting the results (such as that the NHMUK rostrum isn't as large or robust as MNSM V4047), but they certainly do not make that much of a difference. Spinosaurus remains just comparable to extant-slender snouted crocodiles such as Mecistops, Tomistoma or Gavialis. Ie there's no evidence for extreme cranial strenght. The low diameter puts it at a disadvantage regarding bending resistance, and the cross-section of resistant tissue, while perhaps pretty big for it's external dimensions, will have a hard time making up for that. Thus it is not wise to assume it was extremely strong when in fact there is absolutely zero evidence for that, but many good indices against it. What Cau proposed on the other hand (and what I have proposed too during our other discussion on the subject) makes a lot of sense and is in agreement with the skull's features; -quick and moderately strong perpendicular biting reduces stresses on the skull -sufficient bite force is fully conceivable due to the dental and mandibular robusticity -teeth are well suited for puncturing and would do so quite efficiently, morphology and location resembles cat canines -teeth are extremely badly suited for tearing -no risky application of large external loads on the cranium and neck are necessary -skull deeper and narrower than skulls of animals that kill by vigorous lateral shakes, indicates strongest loads were withstood in dorsoventral or posterior direction

|

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on Dec 12, 2013 20:45:38 GMT 5

I never said it did. No, having surplus fenestrae does not equal thin walled but rather the density of the skull itself. Allosauroids did not have exceptionally dense and/or heavily-built rostrums despite their overall size in some species. Didn't you agree on that in the Spinosaurus vs Carcharodontosaurus thread? The reason why carcharodontosaurus was capable of withstanding considerable amounts of vertical stress were because of its impressive rostrum depth, not its overall rostrum build, which it lacked in. Carcharodontosaurus was poorly designed (as in skull and tooth structure) for gripping and resisting lateral forces.

The lateral shaking argument is now going extinct, but rather a vertical shaking argument is more possible. This would not require a powerful bite in itself, as the sheer force of the spinosaurus' jaws would not be relevant here. An actual powerful bite force is only necessary for the quick killing technique that Broly suggested. Spinosaurus lacked an exceptionally powerful bite in this regard, as its thin jaws did not provide for really powerful jaw muscles. Due to its gripping (as opposed to crushing) snout morphology, a reasonably high bite force is just not likely.

It's ability to withstand lateral stress in itself was quite high, actually, but that is attributed to its gripping morphology.

While you are correct there, the main problem I have with the perpendicular biting hypothesis is that, again, spinosaurus was not designed for delivering exceptionally forceful bites, but was again (yes, just like crocodiles) designed for gripping. This makes the vertical shaking technique more likely, as it not only does not require a powerful bite, but it is perfectly logical considering the conical and specialized dentition of spinosaurus.

While I am not arguing that spinosaurus' dentition was poorly adapted for penetrating (and was in fact longer and potentially more deadly than that of modern generalist crocodilians at the tip of the premaxilla and dentary and the middle of the rostrum, as well as being perfectly structured for deep puncturing), I am arguing that spinosaurus was, again, adapted for piscivory, making lethal perpendicular biting somewhat hypothetical and unecessary.

The dental robusticity, while quite high, is not necessarily an implication for powerful biting but an implication for the kind of animals that were hunted by spinosaurus (mainly large fish). And the snout (while still very dense and strong) was still most definitely lighter in build than the snout of tyrannosaurus, which was your perfect example of a theropod that was not only well suited for crushing but was also characterized by an immensely powerful biting force as well. Tyrannosaurus' skull is very wide, unlike spinosaurus, which is a defining characteristic of its advantage in jaw strength compared to other non-tyrannosaurid theropods (most non-tyrannosaurid macropredatory theropods lacked exceptionally powerful and robust skulls and were more-so adapted for ripping and slicing also evidenced by much less robust dentition. Theropods like this include genera such as Megalosaurus and Allosaurus, which both possess much more lightly-built rostrums and dentition more-so designed for cutting and ripping). Spinosaurus simply lacks this crushing morphology seen in tyrannosaurids. In spinosaurus' case, the robusticity of its teeth are the dependent factor for the kind of prey that it would have taken regularly. This would be a very important adaptation when hunting other dinosaurs.

Cat canines are located at the frontalmost part of their jaws. Spinosaurus' longest and most robust dentition was located in the premaxilla area, frontalmost part of the dentary, and roughly the halfway point of the rostrum. The upper cleft in the rostrum would be an awful adaptation for killing large animals with powerful perpendicular biting due to its 1. Placement (spinosaurus' jaws would be particularly weak here, as the strongest biting force is always at the rear of the snout) and 2. Overall build (very specialized and gracile compared to the proceeding parts of the rostrum. It was designed as a sort of specialized "hook" to catch fish). Of course, the other enlarged teeth located at roughly the center of the rostrum would be a possibility for spinal damage here, but they of course were only located on the rostrum and not the dentary.

Big cats have adaptations for killing large herbivores with neck bites, spinosaurus, despite having relatively similar dentition, does not. Nor does it possess the crushing morphology of tyrannosaurus (and thus does not possess an exceptionally powerful bite force).

Quote: skull deeper and narrower than skulls of animals that kill by vigorous lateral shakes, indicates strongest loads were withstood in dorsoventral or posterior direction

But this could also apply to vertical shaking as well.

|

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on Dec 12, 2013 23:16:28 GMT 5

And although genera like Tomostoma or Mecistops serve as the best analogies for spinosaurus, there are again obvious discerning characteristics including:

Much deeper rostrum and dentary present in spinosaurus

Longer proportional dentition in spinosaurus. Its dentition was probably much stronger than the dentition of modern piscivorous crocodilians, which means that it would be at a much lesser risk of breaking (at least in absolute terms. Spinosaurus' teeth were not largely broadened proportionally).

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Dec 15, 2013 16:14:56 GMT 5

What count's is the cross-sectional area of bone and how deep that area is in the direction in which it is loaded.

No, they are not "exceptionally dense and/or heavily-built", but they are far deeper and also wider than spinosaurid rostra, and the exact extent to which they were pneumatised internally is an unknown to us, even in Spinosaurus.

I agree that that's probable, but of course I was speculating just like you.

I don't quite understand you. Spinosaurus has no "much thicker and more generalized rostrum than Mecistops", and if it had, your point wouldn't apply.

crocodilians have such "gripping rather than crushing" dentition, and yet they produce very high bite forces. Cats have puncturing teeth, and they too produce very forceful bites.

"its thin jaws" are a hindrance for resisting forces, which limits non-adductor-driven forces just as much as adductor-driven ones.

You misunderstood me. The width is what counts, and what would be expected as an adaption to increase lateral resistance if this was a factor it heavily depended on. Whether it's jaws were round in cross-section isn't really important.

I'm really bad at beam theory (something a physics-enthusiast should cover in a separate thread), but If I got the stuff right, it's always preferrable to have as much width and tissue in the direction that is loaded, to resist bending and fail in shear in that direction.

Of course it was, that's what it was adapted for. It's just a moderately powerful perpendicular bite would both be fully conceivable and the most likely option outside what it was specialized in (that is, gripping fish and pulling them onto dry land)

It would not really do anything other than a perpendicular bite would, no force greater than the yield strenght of the rostrum could be excerted, and the teeth would puncture into the prey.

I doubt bite force would be a limiting factor, considering the deep, robust dentary of Spinosaurus. What it could excert by "vertical shaking" (with which I think you primarily refer to ventroflexion because dorsiflexion would require the jaw muscles to be just as strong as the force excerted in it to keep the jaw from being forced open), it could also excert via traditional, perpendicular biting.

I wouldn't say "unnecessary", but rather "subsidiary".

One more reason it would probably use a comparatively unspectacular approach to do it when necessary (when it happened to prey on terrestrial prey), by just utilising what it already needed anyway.

it tends to be also an indication for a reasonably strong bite.

I wasn't suggesting a killing style anywhere comparable to Tyrannosaurus, which forst of all employed a crushing bite at least 2-3 times stronger than Spinosaurus, and secondly used vigorous shaking, ripping and perhaps even torsional forces to cause internal damage of what it bit (ie, totally destroy a vertebral collumn or skull).

For S. aegyptiacus I merely suggest it used a precise, quick puncturing bite, something for which it's bite force and skull strenght would probably be sufficient.

Again, nowhere was I comparing it to T. rex in some way. I was actually arguin it did not kill by brute force in a way comparable to Tyrannosaurus, or by horrendous exanguination like Carcharodontosaurus.

btw I wouldn't be that sure about Megalosaurus being a slicer. It's type demonstrates a pretty robust dentary, and long crowned, wide teeth, which would be rather atypical, and other megalosaurs also display features rather consistend with specializations for bite force (large, robust, banana-shaped teeth, robust mandibles, deepened jugal) and crushing.

Robusticity of one part is useless without sufficient strenght of adjacent parts. What use is a strong tooth if it is stuck in a weak jaw? What use is a laterally strong skull if it has thin ziphodont teeth designed for slicing in it?

Those teeth would not require that great a force to puncture deeply, after all that's what they are adapted for. They focus all the force on a very small tip area, which makes the pierce stuff easily.

And as you argued before, Spinosaurus' rostrum is not that weak either, even tough it's not particularly strong. There is no proper reason why a diastema should be that disadvantageous for killing large animals.

you don't need a particular adaption for killing with a neck bite. The neck is a vulnerable area. If you've got sharp teeth, you sever the jugularis or carotids, if you have conical teeth you clamp down and close the windpipe.

Perhaps, but why should it?

|

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on Dec 15, 2013 20:29:54 GMT 5

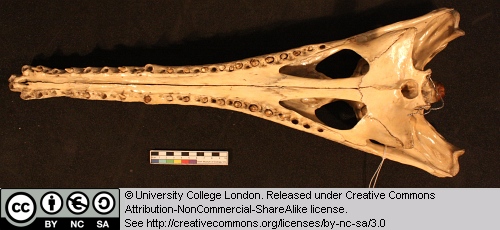

Yes but what we still have in spinosaurus is a comparably more robustly-constructed rostra, specifically when looking at it laterally. The walls of spinosaurus' rostrum were particularly more solid and less pneumatic, and when looking at it ventrally, you can notice that, while spinosaurus' rostrum was not a 100% solid piece, it was definitely more-so than it carcharodontosaurus (whose rostrum was much more of a hollow and lightly-built structure). The bottom line is that both animals were adapted to exist in their respective niches: spinosaurus was adapted to hunt fish (had surplus amount of gripping morphology) and carcharodontosaurus was designed to kill with ripping where a strongly-built skull is less of a necessity, as it only needed to be used vertically. Ok, maybe mecistops is a little bit over the top. But that does not take away the fact that, most of all, spinosaurus was definitely comparable to the false gharial or freshwater crocodile in terms of snout width. It was not, by any means, comparable to the Indian gharial; spinosaurus' snout was far more robust and a good deal better designed for gripping powerful animals than the comparably more gracile and lightly-built snout of the Indian gharial, which was only well designed for coping with particularly small fish overall (which we know for a fact that spinosaurus was adapted to hunt fish like decent-sized mawsonia and onchopristis):  And take a look at this skull reconstruction in Chiba, Japan:  Compared to the African slender-snouted crocodile (on the top):  And here is the false gharial:  Spinosaurus had a generally more robust rostrum than tomistoma at least; it was around the same width and specialization but yet it was considerably deeper and was designed for tackling rather huge-sized fish. In spinosaurus, its snout was quite well designed for reasonable multidirectional resistance which is yet another logical reason to believe that it was not a weak animal at all (much of its anatomy indicates that it was well adapted for hunting such fish, which is primarily what makes it a strong animal aside from its size and power). Overall, spinosaurus was generally comparable to slender-snouted crocodile species (specifically the false gharial and freshwater crocodile most of all); it had a generally similar rostral build but was yet a deeper and generally more robust piece owing to its likely decent strength in gripping. It was not analogous to the Indian gharial owing to its higher aptitude to hunt rather large and powerful animals without its snout breaking. Although I must add that some old male gharial specimens do get considerably broadened snouts that seem relatively comparable to spinosaurus or tomistoma, but this does not seem to apply to the majority of remaining animals:

That is because macrophagous species have generally wide snouts, which spinosaurus comparably lacks. Of course spinosaurus' bite force wasn't weak, but it was not anything special either. I know for a fact that crocodilian bite force is not dependent on snout shape of course, but I do know that it seems to be homologous if anything in species that do not hunt turtles and shellfish (try comparing a freshwater crocodile and chinese alligator of similar length; both have their own specializations). Of course biomechanics and analyzations of spinosaurus' cranium (which happens to be quite fragmentary) have indicated that members of the spinosauridae family as a whole like did not exert very powerful bites. Unlike tyrannosaurids, their lifestyle did not require such powerful biting but rather simply decent gripping strength and pointed conical teeth. I know that a few various big cats like lions and tigers (and certainly jaguars) are capable of exerted massive amounts of force. But the forces that they exert are not necessarily specialized. Can you give me a study or source that proves that their bites were exceptionally powerful? A MODERATELY powerful bite is logical, but I thought you were talking about excessively powerful bites. In theory, yes. But I feel there is still mandibular and cranial evidence that we need to prove that it had an EXCEPTIONALLY powerful bite. Gotcha. I wasn't sure what you were implying. Megalosaurus teeth:  They appear to be quite similar in shape to allosauroid teeth. Again, I thought you were talking about monstrous biting strength as opposed to moderate biting strength. The diastema itself would have been highly vulnerable in the event that spinosaurus goes for a large terrestrial animal. The vulnerability factor would be much less if the spinosaurus managed to completely wrap its maw around the neck of a prey animal. In a way, perhaps. But you must remember that they were not designed in quite the same way as those of macrophagous crocodilians or tyrannosaurids; they were generally very sharp and were best designed for piercing particularly deeply without heavy reliance on bite force. Spinosaurine dentition was best adapted for piercing the hides of fish efficiently, so a powerful bite is not a necessity. The teeth of spinosaurus were designed much like pointed spikes if anything to pierce, not crush. Being strong and being finely pointed are two different things. Spinosaurus' teeth were designed for puncturing because that is how they killed and it corresponds with just what they killed, but them being strong is merely a feature to prevent fracturing of the tooth in gripping. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Dec 15, 2013 22:13:07 GMT 5

Why should it be? Being deep just isn't near as advantageous as being wide for lateral resistance (and vice versa for vertical resistance). Since when is a deep rostrum a disadvantage something "suffers from"? It is an advantage that enhances dorsoventral strenght, and, to a smaller degree, lateral strenght. I concede it's disasvantageous if the snout should have a small area to reduce friction, eg. to have reduced water resistance, but besides that, it's beneficial. What you can note is that Spinosaurus certainly has a deeper skull than these crocodilians, but theirs tend to be wider and more flattened. There was no such thing as "emphasis on their rostrums being deep", the paper simply calculated the second moment of area and polar moment of inertia based on the specimen's cross section. This is of course affected by estimates how large the rostral fragments are compared to the whole skull, and it's relevance depends on how typical a representative their specimen is, but no other "emphasis" plays a role. That's MNHM you are referring to, the Dal Sasso rostrum. As you have seen the rostrum in Cuff & Rayfield is less robustly constructed and smaller-which is probably the reson for it being outperformed by all the other studied specimens (please officially note that I have no clue on how much of the rostrum they assumed to correspond to the 18.5% of total skull lenght the Baryonyx specimen was assumed to constitute). For MNHM I think slender-snouted crocodiles are a decent analogy. and they have those because they excert bite forces as great as a Spinosaurus that's 12 times their size, and, on top of that, violently shake their prey-not because they have a moderately strong bite sufficient to drive a a few teeth ideally suited for puncturing into a prey animal. In any case their bites are powerful enough to puncture the skulls or spinal medullae of decent-sized prey animals, that's proof in itself. their bites are strong enough to utilise a precise puncturing bite, which is what I suggest spinosaurus did against mid-sized terrestrial prey. coherentsheaf once showed me a study that found a tiger could excert a bite force of 7 000N, but I forgot the name (I think it was CF on the "nanotyrannus vs Ngandong tiger" thread). That may have been a bit ill-phrased. What I meant to say; I'd be more similar to crocodilian's in shape. We'd expect it to have an emphasis on width, which is usually correlated with a reduced emphasis on depth. Of course it's fully possible it'd be deeper, but it would still have to be broad enough. What I found interesting in this regard is fig. 5 in Cuff & Rayfield. The compared regions were mainly the diastema in Spinosaurus, which may explain it's very low scoring, since that region is rather gracile both dorsoventrally and laterally in Spinosaurus, but deepened in Crocodilians and Baryonychines (perhaps like the expansion in the anterior dentary of carcharodontosaurines?). it seems the results show a bias against Spinosaurus since the supposedly weakest part of it's rostrum was studied (not the part posterior to it where the largest teeth are located). A comparison of the whole preserved rostrum with the corresponding region in crocodilians would have been more interesting. But still, nowhere would I consider Spinosaurus' skull much more resistant than an adult Mecistops; I think they are pretty good analogies overall. It would not be weak laterally just because the rostrum was relatively deep. At equal with, a skull that's deeper will have the higher lateral resistance. Nope. They would be relatively irresistant (relative to their own and their skull's overall size and power of course), because their skulls were not reinforced in this direction but engineered to be light but strong in another, but they'd be even more irresistant if their skulls wheren't just relatively narrow but also shallower. Lol of course not. Haven't I previously stated on this thread I thought ~2t was an accurate estimate for it's bite force? Megalosaurus teeth: actually, no, they appear longer, have a stronger curvature and also seem wider and to have straighter carinae. Not totally Tyrannosaurus-like, but not that Allosaurus-like either. I think assuming the latter two to have the same biting mode isn't wise. as I highlighted for several times, Monstrous biting strenght wouldn't be necessary for the biting mode I proposed the most likely: It depends. How kinetic is the structure? Is it loose and are there elastic ligaments holding it in place, like in dilophosaurids? in that case, it would shurely bend, but not fail. Is it a firmly sutured and entirely bony connection? It'd be pretty vulnerable to fracturing, but only given it makes powerful contact with the prey, something it doesn't have to do, since the teeth It'd likely use for killing are posterior to it. All that isn't well-studied enough. I presume it's not good at transmitting force, but no hindrance for another part of the rostrum doing that. |

|

Fragillimus335

Member

Sauropod fanatic, and dinosaur specialist

Sauropod fanatic, and dinosaur specialist

Posts: 573

|

Post by Fragillimus335 on Dec 15, 2013 22:42:02 GMT 5

Does this make sense? It seems unlikely that Spinosaurus would have a bite force weaker than a 5.2m saltwater croc.  |

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on Dec 15, 2013 23:38:50 GMT 5

Because an animal with an impressively deep rostrum would not necessarily require a strong resistance to lateral stress, as their killing style would revolve around vertical techniques.

I did not mean "suffer" literally. I simply meant that cacharodontosaurids were characterized by particularly narrow jaws.

Again, do not take all of my terminology literally. Biologically, spinosaurus was characterized by a relatively deep rostrum/dentary, thus it is logical to call that "emphasis on depth". It had nothing to do with the actual tests.

So the reconstruction in Japan is MNHM? Well then there you have it; that specimen has a quite robust rostrum (which is where most of my plights in regards to dental and snout robusticity and morphology come from), which is why I feel it was unwise to use a more gracile specimen in this case.

I agree, even though there are still obvious differences that I pointed out earlier in this thread.

If I am not mistaken, the only pantherine that often crushes prey animals' skulls is the jaguar. I am unsure about tigers doing this.

Are you referring only to the specimen used or the considerably more heavily-built MNHM specimen?

Well there you have it. Using the entire rostrum of the more robust morph (the Japanese one) would have been more wise. The lateral strength of the entire rostrum would have most likely been reasonably higher due to the more broadened center and rear of it compared to the premaxilla.

The skulls of allosauroids in general were adapted for vertical killing, as evidenced by their impressive depth, little emphasis on width (although some groups like allosauridae had reasonably wider jaws in relation to depth), and thin dentition (which would have obviously been horrible for gripping). Their jaws were still very lightly-built too (put two and two together: narrow jaws that were very sparse and lightly-built), so impressive lateral resistance is likely not a characteristic of any allosauroids; it is not necessary and it would have been unnecessary to put so much extra and unneeded stress on the skull.

That is basically what I said.

Oh well. I have not studied megalosaurids very thoroughly. What I know is that AT LEAST they were less specialized for crushing and force-related killing tactics than tyrannosaurids, and were still very well adapted for ripping. Again, I never claimed that they killed in the same exact way as allosaurus (their stronger curvature would make a powerful downward strike much more subtle), but their dentition was certainly very thin and the curved shape/heavy serrations would allow for easy backward ripping.

Quote: but theirs tend to be wider and more flattened.

But the veralp build of spinosaurus' rostrum appears to have been far more robust as evidenced by its particularly deeper rostrum in conjunction with its relatively wide rostrum in addition

|

|