|

|

Post by creature386 on May 25, 2014 14:57:56 GMT 5

Yes, this is possible. It is actually the main reason why crocodiles have such a high bite force because the death roll + violent sharking needs a lot of force to keep the prey in the jaw.

|

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on May 31, 2014 4:05:23 GMT 5

Where have you heard this before? That is definitely a good notion, but I need proof. The powerful biting forces could be attributed also to either the fact that crocodilians are designed to grip but yet larger and more robust forms will often take larger terrestrial prey, or the fact that many such as the American alligator will crush hard-shelled creatures (even to the point where shellfish make up a very good portion of the diet of the Chinese alligator). Still, there is no way in hell that the Indian gharial would be able to use torsion, and nor would it ever take anything bigger than maybe a moderately-sized catfish:  Whereas spinosaurus' snout was a very strong robust piece of bone that could not in any way be considered fragile:  So the possession of a powerful bite in the Indian gharial would likely be evolutionary at best. Spinosaurus was much better adapted for tackling large animals, and was far more analogous to the false gharial if anything. Though it is possible that the forearms and claws of the theropod could have been used for dismemberment, although I am unsure if that would have been the primary purpose (probably second to catching fish) I know I have brought this up far too much. |

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on May 31, 2014 13:18:25 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on May 31, 2014 19:10:29 GMT 5

I do agree that it makes more sense for broad-snouted forms to possess powerful biting forces, but is there any indication as to why more gracile species still are considered forceful biters?

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jun 5, 2014 1:38:16 GMT 5

The gracile-snouted forms do have weaker bites than the robust-snouted ones*, but still bite force correlates way better with body mass than it does with metrics of skull robusticity.

Firstly, that is because those taxa have very large heads. Secondly, they have lower savety factors compared to bite force, and do not require ones as high as crocodilians that employ violent shaking or torsional feeding on large animals. That supports the notion that these types of behaviour are a key selective pressure on cranial robusticity. I could imagine piscivorous forms still benefited from high grip forces in some way, so that they did not reduce their plesiomorphically high bite force as significantly as one might otherwise expect in animals with such gracile snouts, despite their specialization.

That just shows once more that skull strenght is not necessarily a result of high bite force and vice versa.

I suppose many people would object, correctly, if anyone decided to scale up Spinosaurus’ bite force from even something as gracile-snouted as a Gharial, because the evolutionary history of these two animals is entirely different, and hence the reasons why gharial bite force is as high as it is do not apply.

*Taxon representative bite force from Erickson et al. scaled to equal body mass (272kg):

C. porosus: molariform=8983N caniniform=5792N

A. missisipiensis: molariform=7880N caniniform=5144N

M. niger: molariform=7458N caniniform=5294N

M. cataphractus: molariform=5299N caniniform=---

T. schlegelii: molariform=5240N caniniform=3238N

G. gangeticus: molariform=3424 caniniform=1670N

|

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on Jun 5, 2014 2:10:29 GMT 5

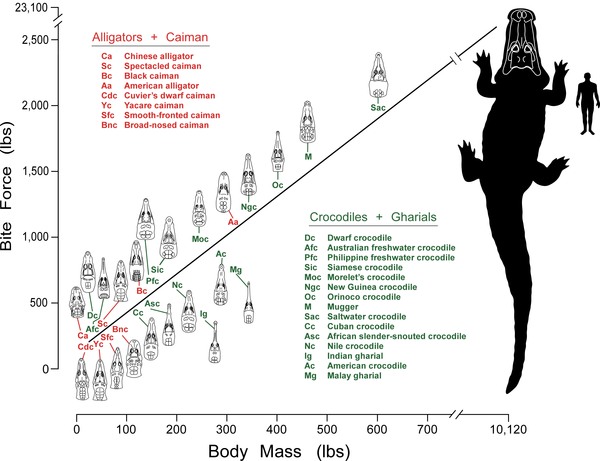

If this table is correct, there is still a general trend going on regardless of snout shape (although the Indian gharial does seem to be a major outlier):  It seems as though the Orinoco and freshwater crocodiles have established a similar pattern with more robust-snouted forms like the American alligator and spectacled caiman for example, while the broad-snouted caiman (which I believe has been proven to have had the widest snout relative to length in all of crocodylia) is below the line of best fit. I am unsure how accurate this is, but the point still remains that crocodilian bite force correlates primarily with size as opposed to snout shape and diet (although the usage of that power could vary in that I believe gharials can "focus" that power into sharper tooth points for more effective feeding). So a proportionally large head is correlated with a strong bite force? It relies on the musculature and cranial anatomy, not head length (I believe, correct me if I'm wrong). Such an elongated head would make violent shaking for that certain species very risky, and as such a strong biting force would be unneeded (both in that regard and in the sense that they would be far less sound for crushing). I am no doubting anything BTW, just need clarification (why did they have such powerful bites if it was unneeded, not "what was their biting force" if that helps you understand my plight better; "why" vs "what") Assuming you are replying to this question that I just posted: "I do agree that it makes more sense for broad-snouted forms to possess powerful biting forces, but is there any indication as to why more gracile species still are considered forceful biters? ", where does this fit in? It seems you are talking about spinosaurus, which was irrelevant in that question. If you were referring to longistrine crocodilian snouts: that would be the very reason that would make forceful biting unnecessary; if they could not utilize it fully without injury occuring, why even have it in the first place aside from simple evolutionary factors? Ah, this was practically my idea. It definitely seems logical that powerful biting is a plesiomorphic condition to begin with, but this does not seem to be proven anywhere officially. It certainly seems logical considering the megalosaur ancestry vs the crocodilian ancestry that the biting forces would differ greatly, despite the obvious morphological similarities between spinosaurus and modern longistrine crocodiles |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jun 5, 2014 16:00:37 GMT 5

Godzillasaurus: Regarding your first point, that is what I wrote. Looking at Crocodylus porosus and Alligator missisipiensis for example, the latter had a wider snout but the former actually has a stronger bite force when corrected for size. However it does appear that Mecistops, Tomistoma and Gavialis has lower bite force than robust-snouted forms at size parity, although not even nearly as much as one would expect from their snout shape. Yes, a proportionally large head also means proportionally large bite musculature, even if that head is elongated. Crocodilians alltogether have way larger heads than for example similar-sized carnivorans do. Considering a gharial can have a really huge skull, it is not surprising its bite is quite powerful in absolute terms, even though said skull is fairly gracile. You can apply that to all sorts of animals, absolute size of the biting apparatus matters of course. Besides I think that is important for all of crocodylia, among the reasons for their extremely strong bites is certainly that they have really huge heads. As I wrote, slender-snouted crocodilians likely have lower savety factors, which is because they do not need ones as high as macrophagous torsional feeders do. As to why exactly their bite forces are as high as they are, I already explained that crocodylians in general having very large heads certainly does play a role here. I don't think their bite forces are particularly strong relative to skull lenght. There likely was no evolutionary reason to reduce them any further.

|

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on Jun 6, 2014 2:02:30 GMT 5

I didn't know this, good info! But what about animals with rather small heads proportionally that also have rather powerful jaws, like gorillas for example? Although hippos are entirely relevant here, because they have HUGE jaws and still a very high biting force

Well creature386 said that another good reason for powerful biting is because it was necessary for predation in broader-snouted species (in gripping larger animals and shaking/rolling). That is definitely possible, but as to why the slender snouted species still have powerful bites is because of their large skulls? This is very confusing, but in that case, the large skull in longistrine forms would be evolutionary where the development of strong biting would be attributed to the use of torsion, rolling, and crushing to feed, at least it certainly seems so.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jun 6, 2014 2:18:57 GMT 5

There are exceptions of course. But having a large head (and do note that large can apply to all sorts of dimensions, not just lenght) is generally favourable in order to have a powerful bite, simply because in a large hit there is room for a large amount of musculature.

Of ocurse there are animals with small heads adapted for powerful biting (gorillas for example have huge chewing muscles) and ones with large heads that are not, so I’m not saying that large-headed animals are in all cases stronger biters than small-headed ones. Just that this explains why even a relatively gracile-snouted animal can still have a decent bite force in absolute terms.

Yes, that is likely the reason crocodiles evolved such huge, strong jaws–to be able to withstand and excert forces of the magnitude we are taliing about here. Slender-snouted forms merely retained relatively powerful bites.

Probably in part. At least that way their bites are stronger than they would be if they had small skulls.

Note that the indian gharial seems to be the odd one out (also in terms of bite force), it definitely displays the most extreme development of piscivorous adaptions among crocodilians. The other slender-snouted forms have higher bite forces, which are probably related to their more generalist diet.

|

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on Jun 7, 2014 2:16:58 GMT 5

Well still the Indian gharial's bite is not laughable, as it still seems to follow the same general trend as more robust species in terms of biting power.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jun 7, 2014 2:28:38 GMT 5

It is definitely an outlier from the typical crocodilian trend. Check the graph you have posted above, or the figures I posted. Its bite is not laughable, but it is not particularly strong either.

|

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on Jun 9, 2014 7:51:50 GMT 5

I am going to upload MY THEORY about spinosaurus feeding, which comes from Animalia Enthusiasts. Note, this is what I think of the animal, and as such you do not have to agree with everything. This is not meant to start a debate (although I do love debating about this stuff), but here it is: "To make this point clear, I decided to make a thread about it. It is a "remake" of my other spinosaurus thread which I deleted because it was so unclear and disorganized. But here we go. It should be a common knowledge fact that spinosaurus was in fact a piscivoruous animal (its diet was made up mostly by fish, as with all spinosaurids, which had similar defining characteristics); that is the bottom line. Unlike the majority of other large predatory theropods, it was not adapted for taking down large prey items (including the sauropods, large theropods, and large crocodylomorphs that it coexisted with). And yes, many people still consider it to have been a weakling because of such. Here is the truth though, spinosaurus was a far cry different from the Indian gharial (which is the only modern crocodilian that feeds on almost exclusively fish in adulthood. Arguably the only truly gracile-snouted crocodilian) in terms of morphology. Its morphology clearly represents that of an animals that was designed for hunting large and powerful fish. For one we have its snout. We have a few complete rostra (upper jaws) to work with, but they are almost nearly complete. The simple fact of it is, they were not very gracile or fragile, contrary to what many believe. Its snout was unique because not only was it very slender but it was as well more-so of a solid structure, whereas the skulls of most other predatory theropods were larger multidimensionally and pneumatic. This structure, in terms of build, was more structurally sound for gripping than that of what some might consider to have been "far stronger than spinosaurus": carcharodontosaurus (which coincidentally likely coexisted with the titular theropod); it was much less pneumatic and more heavily-constructed (whereas allosaur skulls were the direct opposite). As for its width, it was very similar to the false gharial, and was a good deal broader than the snout of the Indian gharial. Here you can see it both in dorsoventral and lateral views, the latter of which represents a deeper profile than all modern slender-snouted crocodilians both generally and proportionally (thus making its overall proportions more even). Its width is roughly similar to the snout of the false gharial:  Furthermore, its dentition (teeth) was unique for theropods as well. While carcharodontosaurus (an animal that was designed for hunting large terrestrial herbivores) possessed thin, serrated, knife-like teeth that were designed for slashing, spinosaurus had what could be considered the direct opposite. Its largest teeth (located in the frontal parts of its snout) were rather slender, sharp, and circular in cross-section while completely lacking serrations for cutting. They were not at all structured for slashing but instead piercing and gripping:  But the overarching question remains, what was its diet? Well fish, for the most part. But like the majority of slender-snouted crocodilians, it most definitely could kill smaller terrestrial animals given its size. What it was adapted to do was plunge its slim but yet robust jaws into the water and clamp down with "decent" strength, where its sharp and conical teeth would pierce the skin efficiently. " Man, this probably annoyed a lot of people... If anything, try not to think too much of it regardless of its accuracy (although I am pretty confident with it), but I do not feel like debating about it again. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 17, 2014 18:10:21 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by Godzillasaurus on Jul 17, 2014 20:02:39 GMT 5

Note that the alligator gar was HUGE (longer than those guys were tall). Spinosaurus would not be hunting anything remotely that large in relation

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 17, 2014 21:20:01 GMT 5

I think that’s self-evident. The point is how large and strong those things are in absolute terms.

What you can infer with a fair deal of certainty for example is that the puncturing ability of Spinosaurus’ bite was vastly superior to that of an axe hit.

|

|