Post by Life on Aug 4, 2010 12:31:15 GMT 5

Dunkleosteus terrelli

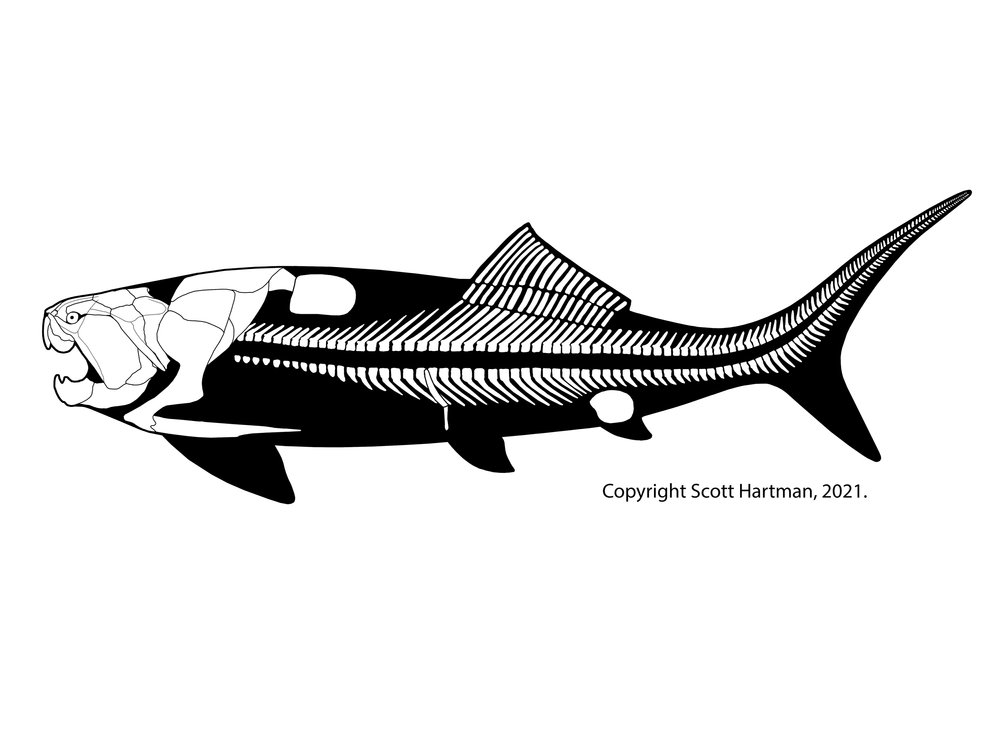

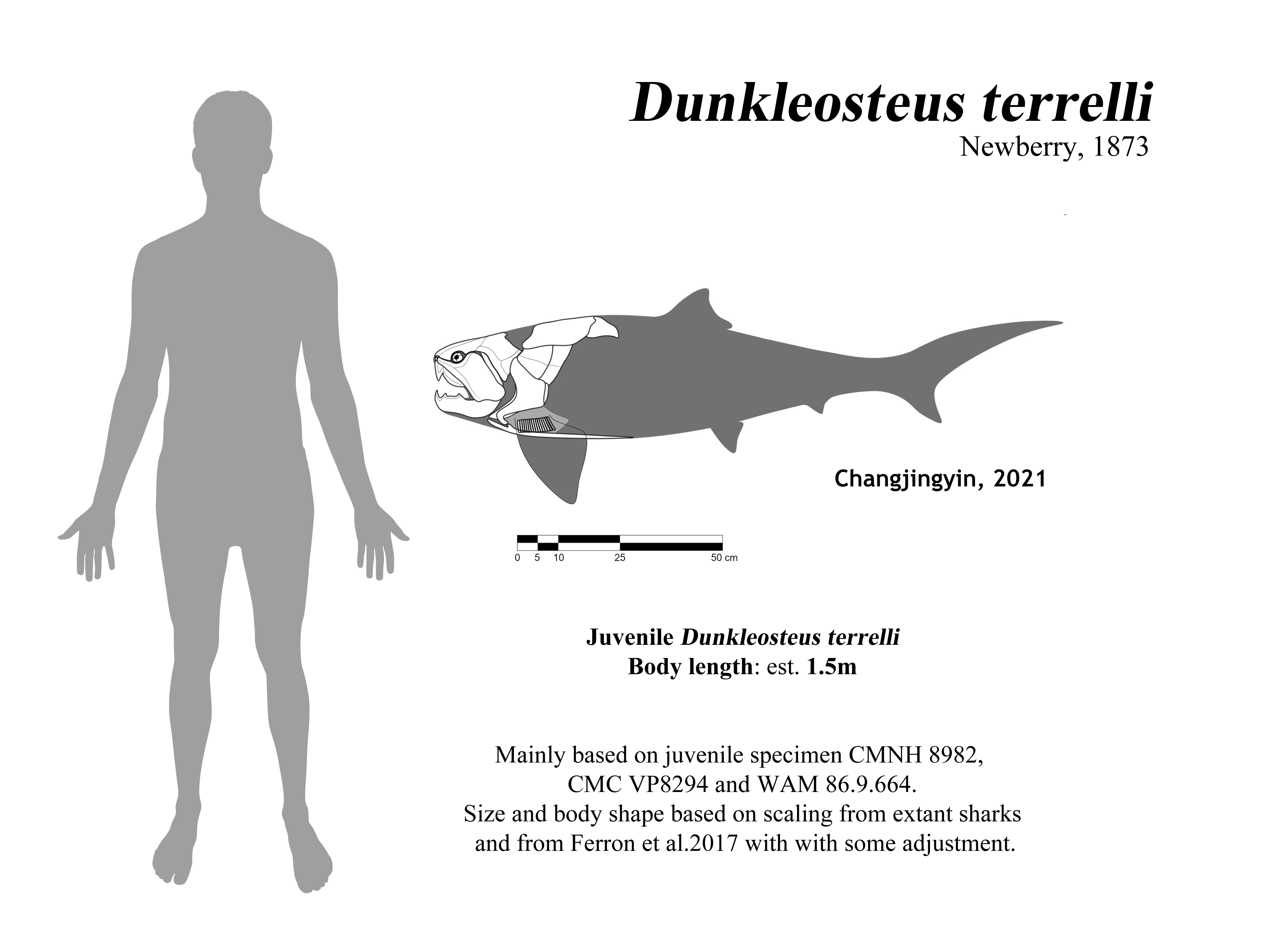

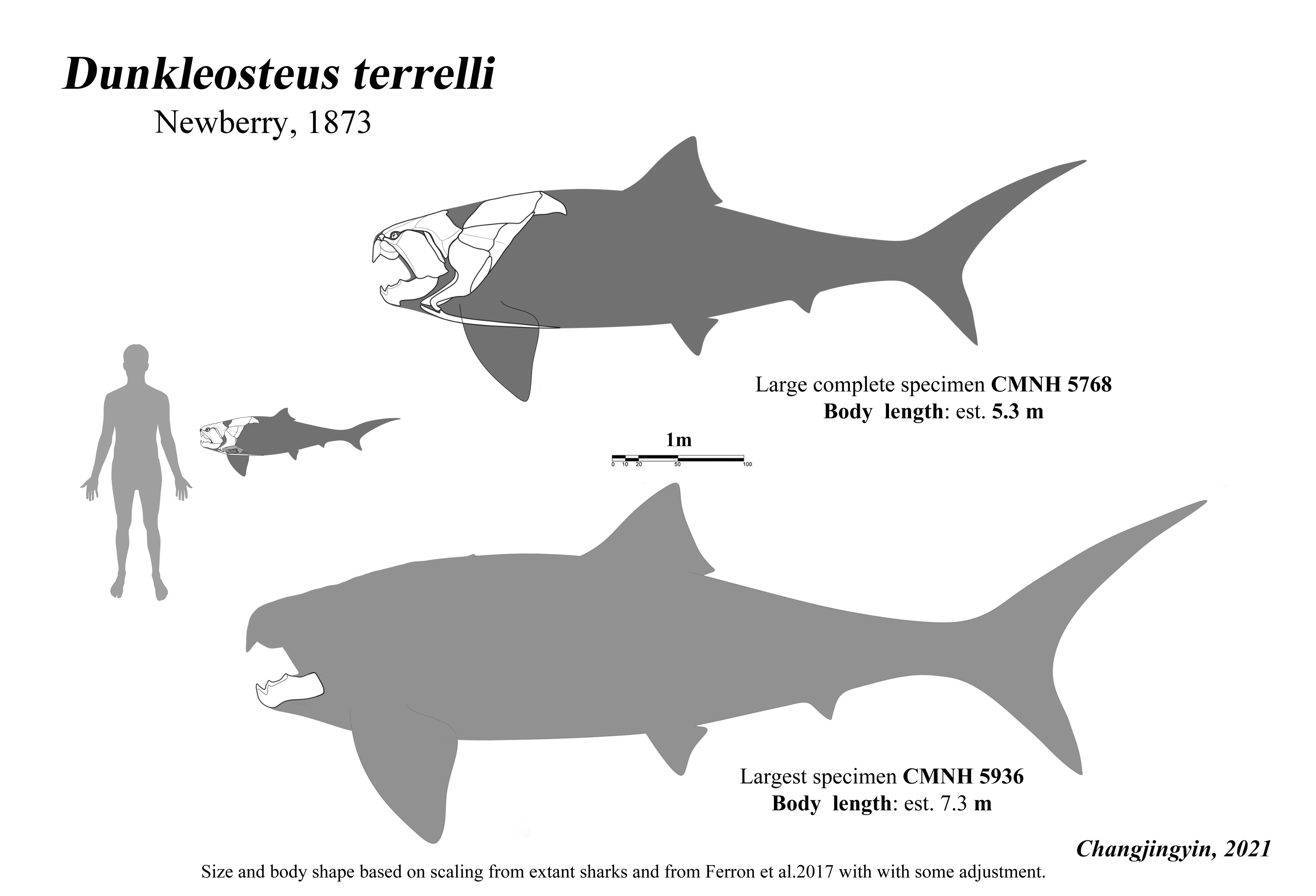

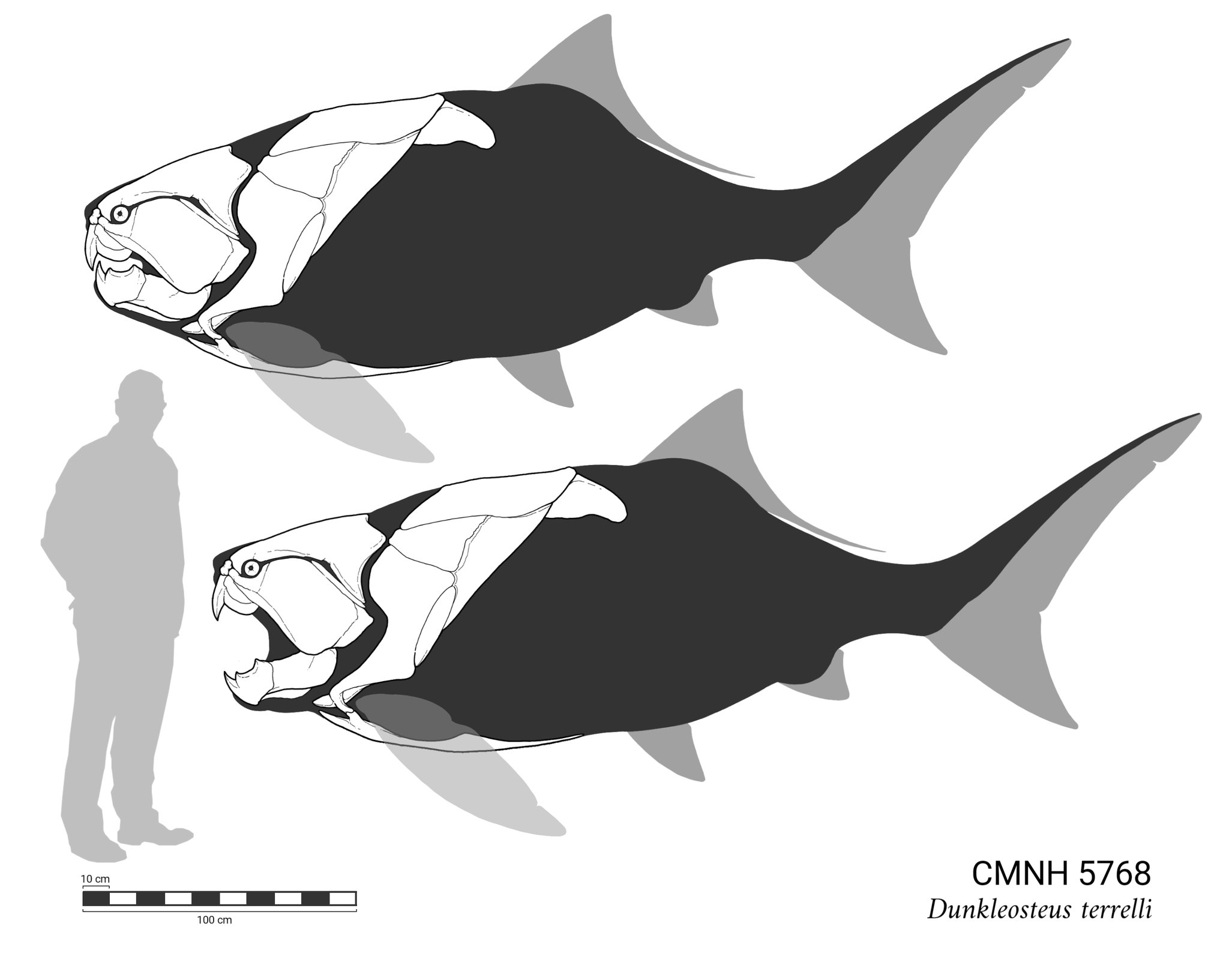

Dunkleosteus terrelli boasted a 20-foot-long body covered with bony plates of armor. Fossil records indicate that this huge fish, one of the first large jawed vertebrates in the ocean, was an aggressive predator.

The razor-sharp edges of bones in this animal's jaws served as cutters. As they rubbed against each other, the opposing jaw blades acted like self-sharpening shears. These bones continued to grow as they were worn down by use.

Source: www.amnh.org/exhibitions/permanent-exhibitions/fossil-halls/hall-of-vertebrate-origins/dunkleosteus

The Cleveland Museum of Natural History has some of the world's best fossil specimens of Dunkleosteus terrelli, including a giant armored skull on display in the Kirtland Hall of Prehistoric Life and a realistic reconstruction hanging overhead.

Dunkleosteus was possibly the fiercest and most terrifying creature alive in the Devonian "Age of Fishes," about 360 million years ago. Up to 30 feet in length and possibly weighing as much as four tons in weight, Dunkleosteus was larger than most other creatures alive at the time. Its huge jaws opened so quickly they created a suction force that pulled prey into its mouth. The closing of its jaws was just as fearsome; its bite was so powerful it could snap a prehistoric shark in two with its razor-sharp jawbones. And yet Dunkleosteus did not have teeth. Instead, the edges of their jawbones kept sharp by rubbing against each other like self-sharpening scissors.

Dunkleosteus is a member of Placodermi (placoderms), the only extinct class of vertebrates that ever evolved. Their heads and upper body were typically shielded by bony armor, leaving the rest of the body able to move freely, powering and steering the creature through water. These armored fishes died out by the early Carboniferous period, which followed the Devonian.

The Cleveland Connection

These long-extinct armored fish lived in the Cleveland area, which at the time—well before humans or dinosaurs existed—was covered by a shallow sea. The sea is gone but the sediments (sandstones and shales) that were laid down during its presence remain. As these rocks erode through the action of water and wind, a rich variety of fossil fish from the Late Devonian have been uncovered and collected. These finds have made Cleveland famous in the world of paleontology.

The largest species of placoderm ever found in the Cleveland Shale is Dunkleosteus terrelli. It was first discovered in 1867 on the shores of Sheffield Lake by local amateur fossil hunter named Jay Terrell, who was one of a group of fossil hunters in the Cleveland area in the late 19th and early 20th century. The early collections of Devonian fossils amassed by this group were passed on to the British Museum, the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and other institutions, because there was not an official natural history museum in Cleveland until 1920.

While the fish fossils are still relatively plentiful, collecting specimens from the Cleveland shale is notoriously difficult. It requires the ability to recognize significant fossils in the rocks, along with the patience to painstakingly extract and reconstruct them, often from fragments.

Today, The Cleveland Museum of Natural History is recognized as a leading resource center for the study of these armored fish. The Museum continues to prepare new specimens collected each year from throughout Cleveland and Ohio.

Fossil Hunting Pioneers

The original fossil-hunting group is credited with many successes. In addition to Dunkleosteus (then called Dinichthys) the group found many specimens of the primitive shark Cladoselache, also plentiful during the Devonian Period in this area but rarely found elsewhere.

Along with Jay Terrell, the group included: Rev. Herman Herzer, a minister and professor in natural science at German Wallace College, credited with first discovering the rich deposits of fossil fishes in the Cleveland area; Rev. William Kepler, a minister and professor of natural science at Baldwin University; two geology professors from Oberlin College, A.A. Wright and E.B. Branson; and many other professional men from around the region.

An honorary member of the group was Dr. John Strong Newberry. Born and educated in the Cleveland area, Newberry went on to join the faculty of Columbia University in New York. It was Newberry who first recognized the significance of the local amateurs' collections, described them scientifically, and ensured that they were passed on to appropriate museums.

Thanks to the work of these early fossil hunters, former Vertebrate Paleontology curator Dr. David Dunkle, and countless experts and enthusiasts over the years, the mighty Dunkleosteus terrelli continues be a source of wonder and study within the permanent collection of The Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

Source: www.cmnh.org/site/AtTheMuseum/OnExhibit/PermanentExhibits/Dunk.aspx

STRANGEST BEASTS TO EVER DIE

by Ann M. Cairns

The Shark Eater: Dunkleosteus

During Earth's "Age of Fishes" 400 million years ago, Dunkleosteus was a genuine sea monster. This aggressive predator, more than 11 feet in length with a skull two feet long, was armor-plated. Instead of mere teeth, it had two long bony blades that snapped and crushed its prey. Dunkleosteus dined on all kinds of seafood including early sharks, which didn't have a chance to diversify and grow to great sizes until Dunkleosteus went extinct about 360 million years ago.

Source: dsc.discovery.com/earth/slideshows/10-extinct-beasts/top-10-extinct-beasts.html

Dunkleosteus terrelli boasted a 20-foot-long body covered with bony plates of armor. Fossil records indicate that this huge fish, one of the first large jawed vertebrates in the ocean, was an aggressive predator.

The razor-sharp edges of bones in this animal's jaws served as cutters. As they rubbed against each other, the opposing jaw blades acted like self-sharpening shears. These bones continued to grow as they were worn down by use.

Source: www.amnh.org/exhibitions/permanent-exhibitions/fossil-halls/hall-of-vertebrate-origins/dunkleosteus

The Cleveland Museum of Natural History has some of the world's best fossil specimens of Dunkleosteus terrelli, including a giant armored skull on display in the Kirtland Hall of Prehistoric Life and a realistic reconstruction hanging overhead.

Dunkleosteus was possibly the fiercest and most terrifying creature alive in the Devonian "Age of Fishes," about 360 million years ago. Up to 30 feet in length and possibly weighing as much as four tons in weight, Dunkleosteus was larger than most other creatures alive at the time. Its huge jaws opened so quickly they created a suction force that pulled prey into its mouth. The closing of its jaws was just as fearsome; its bite was so powerful it could snap a prehistoric shark in two with its razor-sharp jawbones. And yet Dunkleosteus did not have teeth. Instead, the edges of their jawbones kept sharp by rubbing against each other like self-sharpening scissors.

Dunkleosteus is a member of Placodermi (placoderms), the only extinct class of vertebrates that ever evolved. Their heads and upper body were typically shielded by bony armor, leaving the rest of the body able to move freely, powering and steering the creature through water. These armored fishes died out by the early Carboniferous period, which followed the Devonian.

The Cleveland Connection

These long-extinct armored fish lived in the Cleveland area, which at the time—well before humans or dinosaurs existed—was covered by a shallow sea. The sea is gone but the sediments (sandstones and shales) that were laid down during its presence remain. As these rocks erode through the action of water and wind, a rich variety of fossil fish from the Late Devonian have been uncovered and collected. These finds have made Cleveland famous in the world of paleontology.

The largest species of placoderm ever found in the Cleveland Shale is Dunkleosteus terrelli. It was first discovered in 1867 on the shores of Sheffield Lake by local amateur fossil hunter named Jay Terrell, who was one of a group of fossil hunters in the Cleveland area in the late 19th and early 20th century. The early collections of Devonian fossils amassed by this group were passed on to the British Museum, the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and other institutions, because there was not an official natural history museum in Cleveland until 1920.

While the fish fossils are still relatively plentiful, collecting specimens from the Cleveland shale is notoriously difficult. It requires the ability to recognize significant fossils in the rocks, along with the patience to painstakingly extract and reconstruct them, often from fragments.

Today, The Cleveland Museum of Natural History is recognized as a leading resource center for the study of these armored fish. The Museum continues to prepare new specimens collected each year from throughout Cleveland and Ohio.

Fossil Hunting Pioneers

The original fossil-hunting group is credited with many successes. In addition to Dunkleosteus (then called Dinichthys) the group found many specimens of the primitive shark Cladoselache, also plentiful during the Devonian Period in this area but rarely found elsewhere.

Along with Jay Terrell, the group included: Rev. Herman Herzer, a minister and professor in natural science at German Wallace College, credited with first discovering the rich deposits of fossil fishes in the Cleveland area; Rev. William Kepler, a minister and professor of natural science at Baldwin University; two geology professors from Oberlin College, A.A. Wright and E.B. Branson; and many other professional men from around the region.

An honorary member of the group was Dr. John Strong Newberry. Born and educated in the Cleveland area, Newberry went on to join the faculty of Columbia University in New York. It was Newberry who first recognized the significance of the local amateurs' collections, described them scientifically, and ensured that they were passed on to appropriate museums.

Thanks to the work of these early fossil hunters, former Vertebrate Paleontology curator Dr. David Dunkle, and countless experts and enthusiasts over the years, the mighty Dunkleosteus terrelli continues be a source of wonder and study within the permanent collection of The Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

Source: www.cmnh.org/site/AtTheMuseum/OnExhibit/PermanentExhibits/Dunk.aspx

STRANGEST BEASTS TO EVER DIE

by Ann M. Cairns

More than 99 percent of all species that have lived on Earth are now extinct. Sometimes extinctions actually accelerate the evolution of life on Earth. As some forms of life weaken and die off, they create opportunity for other species to grow and flourish. Take a look at these creatures and imagine what life would be like if they had survived!

The Shark Eater: Dunkleosteus

During Earth's "Age of Fishes" 400 million years ago, Dunkleosteus was a genuine sea monster. This aggressive predator, more than 11 feet in length with a skull two feet long, was armor-plated. Instead of mere teeth, it had two long bony blades that snapped and crushed its prey. Dunkleosteus dined on all kinds of seafood including early sharks, which didn't have a chance to diversify and grow to great sizes until Dunkleosteus went extinct about 360 million years ago.

Source: dsc.discovery.com/earth/slideshows/10-extinct-beasts/top-10-extinct-beasts.html