|

|

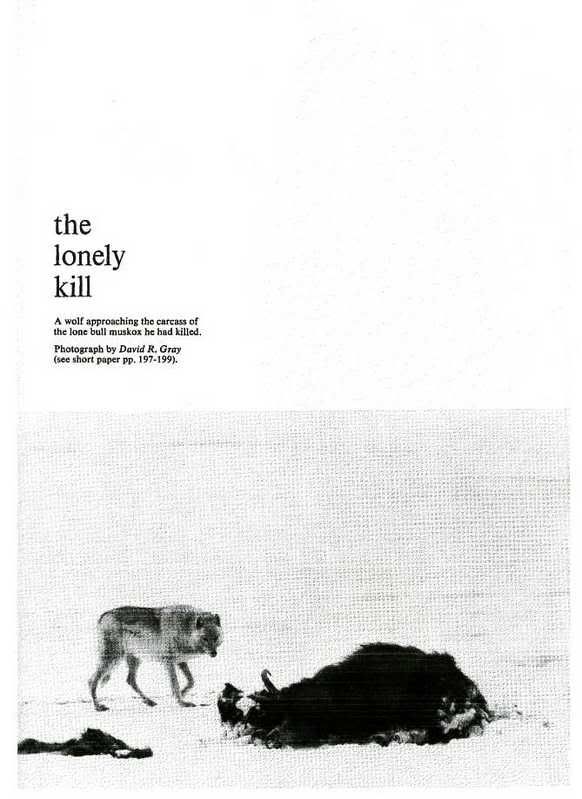

Post by theropod on May 22, 2015 17:37:21 GMT 5

In a marine setting, I can’t think of any (much less any properly described ones). Maybe except for this:  → → EDIT: This used to be a picture of a large sperm whale vertebra with indistinct bite marks. Again, the problems are obvious and the source is terrible, but it looks as if the owner was definitely bigger than 9m. Not sure whether the bite marks were actually fatal or not tough, the surface is somewhat eroded and I can’t really tell whether there are signs of healing. The cetotherid you mean is the one from Clavert Cliffs mentioned by Kent? There is a Brontosaurus specimen mentioned by Matthew (1908), associated with dislodged teeth and with Allosaurus bite marks in its caudal region (which, as I’ve demonstrated before using traumatic pathologies, was commonly targeted by theropod attacks). The Cathetosaurus holotype (BYU 9740) from Jensen 1988, where it was also hypothesized to have been killed by a Torvosaurus or a large allosaurid, has bite marks on its pelvis consistent with a powerful attack. UUVP 5309 ( Camarasaurus ilium), described in Chure et al. 1998 has similar ghashes on its ilium, which could have come from a crippling bite to the gluteal complex. Hunt et al. 1994 describe a number of bite marks on sauropod bones from the Bone Cabin Quarry. They argue them to be scavenging traces, including the first Camarasaur ilium I mentioned (referred to by them as Camarasaurus lewisi, but it appears that Cathetosaurus is actually valid), however their arguments in this respect support the initial hypothesis of a killing or crippling bite (sensu Jensen) just as well.The scores on distal limb bones would also be consistent with tendon-cutting bites, i.e. what komodo dragons do when solitarily killing large prey, and in addition these are not regions that would be considered high priority for a scavenger (even though I would not expect that they would be excempt from scavenging traces either). It is subject to debate what is a killing trace and what was scavenging, and there are almost no cases where we will ever know for sure. The areas were we’d expect to see bite marks to result from scavenging (almost everywhere to be exact) are also those where we would expect them to result from an attack (i.e. regions with important blood vessels and musculature, such as the hip or tail region). So obviously, tooth marks that result from feeding will tend to obscure those that resulted from the killing bites, because we have no real way of differentiating between both and because feeding traces are certainly present in addition to possible killing traces on all prey items. These aren’t any better than the cetothere of course, the placing of the bites makes predation seem very plausible, but it isn’t unambiguous proof. ––– References:Chure, Daniel J.; Fiorillo, Anthony R.; Jacobsen, Aase (1998): Prey Bone Utilization by predators Dinosaurs in the Late Jurassic of North America, with Comments on Prey Bone Use by Dinosaurs throughout the Mesozoic. Gaia, Vol. 15 pp. 227-232 Hunt, Adrian P.; Meyer, Christian A.; Lockley, Martin G.; Lucas, Spencer G. (1994): Archaeology, Toothmarks and Sauropod Dinosaur Taphonomy. Gaia, Vol. 10 pp. 225-231 Jensen, James A. (1988): A fourth new Sauropod Dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic of the Colorado Plateau and Sauropod Bipedalism. The Great Basin Naturalist, Vol. 48 (2) pp. 121-145 Matthew, W. D. (1908): Allosaurus, a carnivorous Dinosaur, and its Prey. The American Museum Journal, Vol. 8 (1) pp. 3-5 |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 22, 2015 20:10:43 GMT 5

|

|

drone

Junior Member Rank 1

Posts: 53

|

Post by drone on May 23, 2015 6:00:49 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 23, 2015 12:39:46 GMT 5

Grey: I've got another candidate: " Incidentally, some Leedsichthys fin rays (perhaps representing the dorsal fin in one specimen, and a pectoral fin in another) do bear evidence of attack by large predators. What look like curving bite marks appear to have been made by plesiosaurs" ---Naish 2009: scienceblogs.com/tetrapodzoology/2009/07/02/biggest-ever-fish-has-been-revised/Unfortunately we have next to nothing on this one, but Leedsichthys is certainly big enough and bite marks on an actinopterygian fin are unlikely to be made by a scavenger.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on May 23, 2015 15:54:01 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by Grey on May 24, 2015 8:32:52 GMT 5

Grey: I've got another candidate: " Incidentally, some Leedsichthys fin rays (perhaps representing the dorsal fin in one specimen, and a pectoral fin in another) do bear evidence of attack by large predators. What look like curving bite marks appear to have been made by plesiosaurs" ---Naish 2009: scienceblogs.com/tetrapodzoology/2009/07/02/biggest-ever-fish-has-been-revised/Unfortunately we have next to nothing on this one, but Leedsichthys is certainly big enough and bite marks on an actinopterygian fin are unlikely to be made by a scavenger. Indeed theropod I had this one in mind too. Btw isn't it contradicting the suggestion by Foffa than pliosaurs were preying on things just up to half their length ? Unless of course these Leeds fishes do not represent large specimens. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 24, 2015 16:09:40 GMT 5

Btw isn't it contradicting the suggestion by Foffa than pliosaurs were preying on things just up to half their length ? Unless of course these Leeds fishes do not represent large specimens. Yes, that is indeed strange. Foffa et al. state so twice, once in the abstract, once in the conclusion. They also imply that except for Leedsichthys, all coexisting prey animals would meet this criterium. However the odd thing is that they at the same time estimated that, at unit skull lenght, both the bending and torsional strengths and the bite force are broadly comparable to the nile crocodile (which in the vast majority of cases, but not exclusively, relies on proportionately small prey, being a generalist just as proposed for Pliosaurus), while at unit body length, the pliosaur undoubtedly has a longer skull. It is suggested that Pliosaurus did not rely on torsion or shaking, but instead used powerful post-symphyseal bites to take its prey apart. That would be supported by a different tooth morphology than in crocodilians. Those of Pliosaurus are actually carinated and thus functionally more similar to T. rex teeth. The problem I see with taking the suggested ratio literally is that I cannot discern the reasoning behind it. Foffa et al. give several other anatomical reasons suporting large prey, and what they mean by 'weak snout' is 'weak compared to alligators and caimans' but comparable to Crocodylus itself. Alligators and caimans incidentally do not take larger prey than crocodiles do, their snouts being more robust notwithstanding. From an ecological perspective the statement makes a lot of sense. Pliosaurs undoubtedly preyed on prey 'up to half their own length' most of the time. But it seems that they took larger prey in certain cases and I see no functional reason to exclude that, since comparably equipped crocodiles can do it. Taylor & Cruickshank (1993) made remarkably similar inferences to Foffa et al., but without imposing an upper limit on prey size. Their explanation was that prey as large as adult Pliosaurus was rare, that it was simply not worth specializing in, and that the majority of its prey would be composed of smaller animals, which explains why it is not adapted for toraional feeding. However they seem to imply Pliosaurus was generalized enough to feed on pretty much anything (again, consistent with Foffa et al.’s comparative resumts for Crocodylus niloticus). I think the likelihood of this just being due to a small Leedsichthys isn’t that big. I don't know what specimen it is, but the smallest of the specimens in Liston et al. 2013 is estimated at 8m, which is roughly consistent with in-situ accounts of the same skeleton (Liston & Noè 2004), while the largest is 16.5m. That means if we follow Foffa et al. to the letter, the minimum length of the responsible pliosaur would have had to be 16m.Such pliosaurs to have existed, but they would naturally be very rare (giant Pliosaur taxa of more conventional size are already rare in the fossil record), and that’s only the absolute lower bound (take larger fishes and it quickly becomes infeasible). I think it is way more likely that a smaller, more common pliosaur was the culprit, attacking an unusually large prey item. ––– References:Foffa, Davide; Cuff, Andrew R.; Sassoon, Judyth; Rayfield, Emily J.; Mavrogordato, Mark N.; Benton, Michael J. (2014): Functional anatomy and feeding biomechanics of a giant Upper Jurassic pliosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from Weymouth Bay, Dorset, UK. Journal of Anatomy, Vol. 225 (2) pp. 209-219 Liston, Jeff J.; Newbrey, Michael G.; Challands, Thomas J.; Adams, Colin E. (2013): Growth, age and size of the Jurassic pachycormid Leedsichthys problematicus (Osteichthyes: Actinopterygii). In: Arratia, Gloria; Schultze, Hans-Peter; Wilson, Mark V. H.: Mesozoic Fishes 5 – Global Diversity and Evolution. Munich pp. 145-175 Liston, Jeff J.; Noè, Leslie F. (2004): The tail of the Jurassic fish Leedsichthys problematicus (Osteichthyes: Actinopterygii) collected by Alfred Nicholson Leeds - an example of the importance of historical records in palaeontology. Archives of Natural History, Vol. 31 (2) pp. 236-252 Taylor, Michael A.; Cruickshank, Arthur R.I. (1993): Cranial anatomy and functional miorphology of Pliosaurus brachyspondylus (Reptilia: Plesiosauria) from the Upper Jurassic of Westbury, Wiltshire. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Vol. 341 (1298) pp. 399-418 |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on May 24, 2015 20:15:34 GMT 5

I should certainly discuss this with Foffa. I still have some difficulties to understand how he determined that prey size was up to half the body length. Indeed, pliosaurs as generalists top predators isn't really surprising given how plenty bigger some species already were compared to the other fauna.

You're sure the teeth marks reported by Naish were found in the specimens described by Liston 2013 ?

Note that Cruickshank 1993 has an interesting claim :

BRSMG Cc332 is an individual with a gape of almost 0.75 m, capable of swallowing, say, ichthyosaurus several metres long whole...

This sounds guessed but in contradiction with Foffa statements that P. kevani couldn't swallow objects in excess of 80cm.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 24, 2015 20:35:16 GMT 5

I could imagine Foffa et al. guessed in their assessment concerning the maximum relative lenght of a prey item for P. kevani. At least I know no other way in which such an estimation could be made, unless they were using an extant analogue (as I wrote, the extant analogue they did use occasionally preys on animals similar to its own size, even tough, due to their completely different built, stuff like cape buffalo may only be half the length of a crocodile that is similar in weight). No, how could I be sure of what Leedsichthys specimen was meant? No information as to its affinities is given, I have got no clue which one it is, or whether it is one of those studied by Liston et al., hence why I wrote "we have next to nothing". It’s just not overly likely to be from something much smaller or larger than the specimens for which there are estimates As in crocodiles, the dimensions of the akinetic pliosaur skull pose a physical limit to the size of prey. In DORCM G.13 675 this limit is quantifiable at approximately 70–80 cm, the distance between the left and right articular surfaces or between the left and right quadrates. In a very conservative case, a prey item of 50–60 cm diameter could theoretically have been swallowed without being seized. That is in all likelihood the same (or almost the same) measurement Taylor and Cruickshank were referring to. The maximum transverse expanse of the jaw rami is the limit to the maximum transverse or dorsoventral width of the prey item being swallowed, not to its length. So "almost 0.75m" is almost certainly not guessed, but simply measured, and what they imply is that ichthyosaurs "several metres" in length would have a diameter small enough to fit through the jaws. Of course it is debatable whether that was actually feasible in real life, due to soft-tissue constraints. But if pliosaurs routinely swallowed their large prey whole, then we can assume they were optimized as well as possible to do so. Note that it appears the westbury pliosaur skull seems proportionately somewhat wider, explaining why the width measurement is almost equal to that of P. kevani despite the length being smaller |

|

|

|

Post by allosaurusatrox on May 25, 2015 3:00:27 GMT 5

Contemporary land: the rare instances of lions killing elephants.

Contemporary sea: orcas taking on blue whales.

Prior land: allosauroids killing Diplodocids

Prior sea: ?

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 25, 2015 3:26:25 GMT 5

Contemporary land: the rare instances of lions killing elephants. Contemporary sea: orcas taking on blue whales. Prior land: allosauroids killing Diplodocids Prior sea: ? In all likelihood megatooth sharks killing large balaenopterid whales, simply because these are the largest marine prey items on record. There is also the possibility that fossil physeteroids could have preyed on similar animals, should it turn out that their temporal ranges overlapped, but then most likely by hunting in groups (being individually less specialized and adapted for such prey, but probably capable of rather advanced social behaviour). Our discussion was specifically about incidences with concrete accounts backing them up btw (I.e. fossils with bite marks or other traumatic damage that resulted from an attack). |

|

|

|

Post by allosaurusatrox on May 25, 2015 3:35:35 GMT 5

Contemporary land: the rare instances of lions killing elephants. Contemporary sea: orcas taking on blue whales. Prior land: allosauroids killing Diplodocids Prior sea: ? In all likelihood megatooth sharks killing large balaenopterid whales, simply because these are the largest marine prey items on record. There is also the possibility that fossil physeteroids could have preyed on similar animals, should it turn out that their temporal ranges overlapped, but then most likely by hunting in groups (being individually less specialized and adapted for such prey, but probably capable of rather advanced social behaviour). Our discussion was specifically about incidences with concrete accounts backing them up btw (I.e. fossils with bite marks or other traumatic damage that resulted from an attack). Apologies then.  Is is there really no solid proof of allosauoid attacks on sauropods? Huh. I knew of the allosaurus vertabrate with a puncture from a stegosaur spike. |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on May 25, 2015 5:26:56 GMT 5

Contemporary land: the rare instances of lions killing elephants. Contemporary sea: orcas taking on blue whales. Prior land: allosauroids killing Diplodocids Prior sea: ? In all likelihood megatooth sharks killing large balaenopterid whales, simply because these are the largest marine prey items on record. There is also the possibility that fossil physeteroids could have preyed on similar animals, should it turn out that their temporal ranges overlapped, but then most likely by hunting in groups (being individually less specialized and adapted for such prey, but probably capable of rather advanced social behaviour). Our discussion was specifically about incidences with concrete accounts backing them up btw (I.e. fossils with bite marks or other traumatic damage that resulted from an attack). Depends what we mean by "large balaenopterids". As you know, bite marks on whales bones are very common but very rarely scientifically studied and quantified. I safely guess that by "large" you refer to balaenopterids at least 9m long, you would rather refer to "gigantic" if the prey items were at least 15m. There are the inferences of Purdy in 1996 about megatooth bite marks on "large balaenopterids" from Pliocene, the Kallal et al. very large balaenopterid subject to an seemingly failed attack from a smaller shark. Godfrey described the wounded healed whale vertebra we see in the Nat Geo doc, possibly a failed ramming by a meg. In the same doc, Lawrence seemed to have evidence of at least feeding on a large Pliocene balaenopterid but this was described in details. Brett Kent unpublished manuscript describes brutal predation on a whale reportedly 9m long. The Bakkersfield whale described in the 2012 Sharkweek was (apparently) dispatched by a megatooth and was estimated at around 7-8m. Then there is Pimiento's theory that this is actually meg extinction which stimulated gigantism in balaenopterids. So I wonder what "large" actually means, even if a predatory shark regularly killing by its own animals about 9m, 9 tons is still very spectacular. I don't know if you take into account co-occurence assumed as predator-prey relationship ? Purdy does alot in his paper.  I always find very impressive that large sperm whales could have served as prey for these sharks. Of course predation is not definitely demonstrated but at least we don't have here the case of the shark avoiding a predator/rival like observed between meg and ancestral Carcharodon and today between orcas and great whites. Sperm whales presence seems to attract Carcharocles in the Pliocene. Regarding bite marks from odontocetes, in his thesis Boessennecker reports that on a total of 300 cetaceans specimens, there is only one certain odontocete (probably physeteroid) bite mark. The lack of bite marks on marine mammals from odontocetes is intriguing to me. Are there no fossil suggestions of predation by theropods on gigantic titanosaurs ? I know there are reported Tyrannosaurus bite marks on Alamosaurus but I agree the primary suggestion would be scavenging. Predation on large diplodocids by allosaurids is certainly confirmed ? |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 25, 2015 14:21:24 GMT 5

That was actually exactly what I was doing, assuming predator prey relationships due to co-ocurrence, as opposed to what we have been doing before (finding concrete accounts). I was assuming he was talking in such general teems becausw he didn't give accounts, or list the accounts already given.

There is already the incidence in Kallal et al., which represents, as you say, a very large animal, attacked, albeit not killed by a small shark. I'm quite confident adult sharks would also attack, and probably succeed in doing so, even though we might not have a specific fossil that shows they did, so they constitute the largest fossil marine prey items.

By "large balaenopterids" I meant such and similar cases, large by balaenopterid standards (i.e. at least in the tens of tons).

I have posted accounts that I think suggest allosauroid predation on diplodocids and basal macronarians, so yes, I think there is evidence for it. Of course there are certainly feeding traces on them no matter what, and I think it goes without saying that that applies to pretty much every prey item that was consumed (I have a hard time seeing C. megalodon only leaving toothmarks in the attack, when proportionately smaller and smaller skulled allosaurids could not avoid hitting bone while feeding). However bite mark distributions are perfectly consistent with various modes of attacks known from theropods and/or extant animals with similar ecology, and thus, just as it is likely that the cetothere discussed earlier was the victim of an attack, it is also likely that these sauropods (or at least some of them) were.

I'm not aware of any comparable evidence for titanosaurs, which is largely because the Morrison Formation has a much better fossil record than localities with giant titanosaurs (hence why they are rarely known by more than two specimens, and usually fragmentary), but obviously I think titanosaurs were preyed on as well.

Could you post a description on those bite marks on Alamosaurus?

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 25, 2015 15:03:21 GMT 5

|

|

→ EDIT: This used to be a picture of a large sperm whale vertebra with indistinct bite marks.

→ EDIT: This used to be a picture of a large sperm whale vertebra with indistinct bite marks. → EDIT: This used to be a picture of a large sperm whale vertebra with indistinct bite marks.

→ EDIT: This used to be a picture of a large sperm whale vertebra with indistinct bite marks.