Cheetah Prey Preference By Reddhole

Cheetah Here is the study:

www.zbs.bialowieza.pl/publ/pdf/1596.pdf Abstract

As a charismatic carnivore that is vulnerable to extinction, many studies have been

conducted on predation by the cheetah Acinonyx jubatus. Cheetah are generally

considered to capture medium-sized prey; however, which species are actually

preferred and why has yet to be addressed. We used data from 21 published and

two unpublished studies from six countries throughout the distribution of the

cheetah to determine which prey species were preferred and which were avoided

using JacobsÂ’ index. The mean JacobsÂ’ index value for each prey species was used

as the dependent variable in multiple regression, with prey abundance and prey

body mass as predictive variables.

Cheetah prefer to kill and actually kill the most

available prey present at a site within a body mass range of 23–56 kg with a peak

(mode) at 36 kg. Blesbok, impala, ThomsonÂ’s and GrantÂ’s gazelles, and springbok

are significantly preferred, whereas prey outside this range are generally avoided.

The morphological adaptations of the cheetah appear to have evolved to capture

medium-sized prey that can be subdued with minimal risk of injury. Coincidentally,

these species can be consumed rapidly before kleptoparasites arrive. These

results are discussed through the premise of optimality theory whereby decisions

made by the predator maximize the net energetic benefits of foraging. Information

is also presented that allows conservation managers to determine which prey

species should be in adequate numbers at cheetah reintroduction sites to support a

cheetah population. Conversely, these results will illustrate which potential prey

species of local conservation concern should be monitored for impact from

cheetahs as several species are likely to be preyed upon more frequently than

others.

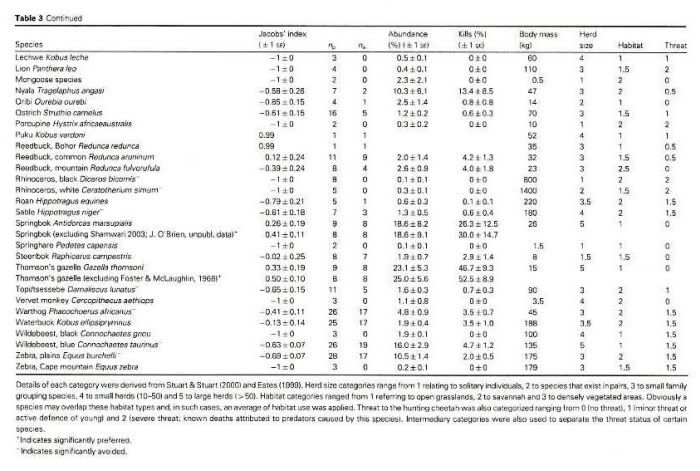

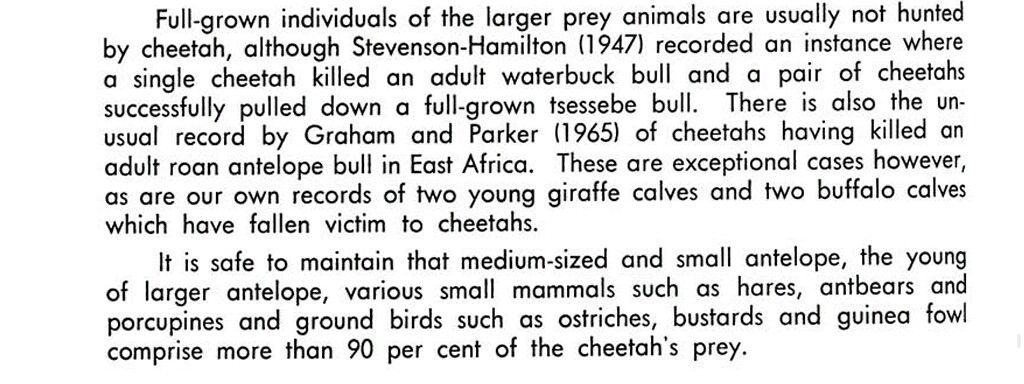

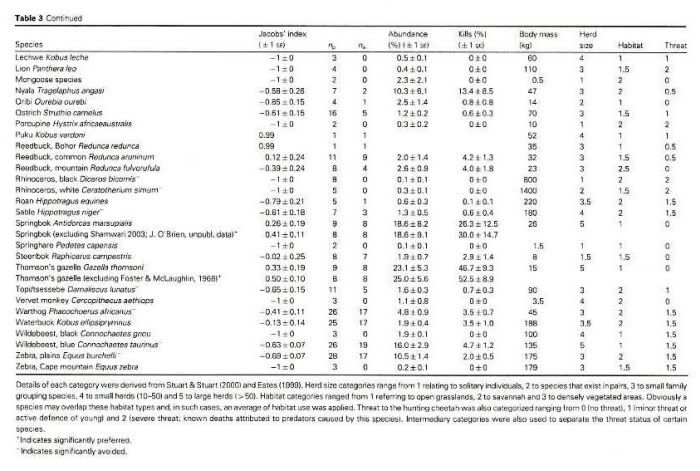

Here are the details on the specific prey species. Species with a small + or - next to them have enough data to be "statistically significant" (i.e. baboon, blesbok, bush pig, etc.).

___________________________________________________________

Iranian cheetahs GPS-collared for the first timeSaturday 3 March 2007

Biologists from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) have fitted critically endangered cheetahs in Iran with Global Positioning System (GPS) collars.

Thismarks the first time this population of Asiatic cheetah can be tracked remotely. WCS is working with the Iranian Department of Environment to protect the Asiatic cheetah found only in the extremely arid habitat around Iran's Kavir Desert.

The conservation groups that on 60-100 Asiatic cheetah remain in the wild, making it one of the world's most endangered cats."This is an amazing milestone in securing the long-term future for the Asiatic cheetah," said Wildlife Conservation Society biologist Dr. Luke Hunter, who led the international team. "We know very little about the important ecological needs of the species in Iran except that they require vast areas for their survival. Understanding their movements as they travel between reserves is one of the first steps in establishing a plan to secure and connect the few remaining populations of this incredible animal." Pictures afterwards ->

WCS notes that the population of the species has fallen significantly since the early years of the 1979 revolution in Iran. "Once ranging from the Red Sea to India, the Asiatic cheetah today is hanging on by only the thinnest of threads," WCS stated in a release. "In the 1970s, estimates of the number of cheetahs in Iran ranged from 100 to 400 animals. But widespread poaching of cheetahs and their prey during the early years of the 1979 revolution, along with degradation of habitat due to livestock grazing, have pushed this important predator to the brink of extinction. Historically cheetahs have played a significant role in Iranian culture, being trained by its emperors to hunt gazelles in ancient times."

Elsewhere the Asiatic cheetah has gone extinct. WCS says that they disappeared from most of the Middle East about 100 years ago and India in 1947. "These captures herald a new era of conservation in Iran," added Dr Hooshang Ziaie, Iranian biologist and director of the project in Iran. "This is the first time we have successfully deployed these collars in Iran, and the data they provide will enable us to make very specific recommendations for conserving cheetahs for future generations. We are delighted that this international collaboration is producing such important outcomes."

news.mongabay.com/2007/0301-cheetah.html Female Asiatic cheetah captured with a remote camera in Iran.

Female Asiatic cheetah captured with a remote camera in Iran. A male cheetah held securely but gently in a ‘soft-catch' foot-hold snare. The technique is one of the safest ways to capture cheetahs and allows scientists to sedate the animals for radio-collaring; both recent captures took place without a hitch.news.mongabay.com/2007/0301-cheetah.html

A male cheetah held securely but gently in a ‘soft-catch' foot-hold snare. The technique is one of the safest ways to capture cheetahs and allows scientists to sedate the animals for radio-collaring; both recent captures took place without a hitch.news.mongabay.com/2007/0301-cheetah.html___________________________________________________________

Impressive Widebeest Kill by a Cheetah Coalition :___________________________________________________________

Male Cheetah Bark Triggers Female OvulationMatt Kaplan

for National Geographic News

January 9, 2009

Male cheetahs turn females on—literally.

That's because a specific bark triggers the female reproductive system to release eggs, researchers have found.

Unlike other cat species, female cheetahs ovulate rarely and at unusual times. They also lack a regular reproductive cycle.

All this makes them tough to breed in captivity.

But now, scientists know why—and the discovery may boost efforts to breed the rare cats.

A team of bioacoustics experts studying cheetah vocalizations stumbled onto the discovery.

They noticed that the male's "stutter bark" was made days before breeding took place, said research leader Matt Anderson at the San Diego Wild Animal Park.

Because calls unique to a single gender are often associated with reproduction, Anderson and his colleagues took a closer look.

Heightened Hormones

The team introduced a sexually mature female cheetah to two males during a series of experiments, recording calls made by the cats and monitoring the hormones found in their feces.

They discovered that male stutter-bark calls triggered increases in the reproductive hormones estrogen and progesterone in the females' feces.

By recording and analyzing stutter-bark rates, the researchers showed that increases in stutter-barking steadily raised the female reproductive hormones responsible for ovulation.

"We never expected to see such a tight link between the vocalization and the hormone levels," Anderson said of the research, which has not yet been published in a journal.

"This came a real surprise."

Conservation Boost

The finding has big implications for breeding the rare cat, the researchers said.

The cheetah has an estimated adult population of only 7,500, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The only known wild cheetah population outside of Africa today is a critically endangered group of fewer than a hundred in Iran.

"I think this just goes to show that telephone sex evolved before telephones," said co-researcher Fred Berkovitch, an ecologist at the San Diego Wild Animal Park.

"By documenting how sound makes animals horny, we hope to improve conservation-breeding programs."

Booty Call of the Wild

Using sound to jump-start reproduction is common among birds, but in mammals it is almost unheard of, experts say.

Male red deer are known to roar to advance the timing of ovulation in females, for instance.

But a male mammal using a signal to activate a reproductive cycle in a female has never been observed before.

Dan Blumstein, an ecologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, said the findings were "neat, but not unexpected."

The new research illustrates nicely how much can be done to improve breeding of endangered species by watching behaviors and studying hormones in the animals' waste, Blumstein added.

Call it "ovulation on demand"—a bizarre bark from a male cheetah (above, a young male in Africa) jump-starts a female cheetah's reproductive system, scientists said in late 2008.

Call it "ovulation on demand"—a bizarre bark from a male cheetah (above, a young male in Africa) jump-starts a female cheetah's reproductive system, scientists said in late 2008.

The discovery may explain why cheetahs are so hard to breed in captivity.news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2009/01/090109-cheetah-ovulation.html_________________________________________________________

Speedy cheetahs put through pacesBy Rebecca Morelle

Science reporter, BBC News

Scientists are attempting to discover exactly what makes cheetahs the fastest running animals on the planet.

A Royal Veterinary College (RVC) team is using high-speed cameras and a sensitive track to monitor the big cats as they sprint.

Cheetahs can reach speeds of at least 104km/h (64mph) and they can achieve their top speed in just a few paces.

The study is being carried out with North African cheetahs from ZSL Whipsnade Zoo.

Professor Alan Wilson, head of the structure and motion laboratory at RVC, said: "The cheetah is fascinating because it can run 50% faster than any of the other animals we are familiar with, so in terms of understanding what limits how fast you can run, the cheetah is a wonderful animal to study."

Chasing chickenJust as most domestic cats cannot resist chasing a piece of string, cheetahs also find the temptation of some twitching twine too difficult to ignore - especially if a tasty treat is dangling from the end.

The lure of some string to play with is to difficult to resist

The lure of some string to play with is to difficult to resist So the research team entice the zoo's cheetahs to run by attaching some choice chicken pieces - wings and feet are a favourite - to a loop of fast-moving string that is pulled along the enclosure by an electric motor.

And as the cats chase the chicken feast, four high-speed cameras, which record at 1,000 frames per second - compared with 25 frames per second for standard cameras - capture their every move.

Penny Hudson, a PhD student at RVC, said: "We use two cameras on each side of the enclosure so we can see the cheetah from both sides.

"When a cheetah gallops, it does different things with either side of its body - it has an asymmetric gate."

The scientists are also using special plates that are embedded within cheetahs' running track.

Miss Hudson explained: "The plates are like sophisticated weighing scales that are able to measure all the forces going through their legs."

Lightning BoltThe scientists are going to compare their results with other studies that have been carried out on greyhounds, which can reach top speeds of approximately 60km/h (40mph).

The researchers are comparing how cheetahs and greyhounds run

The researchers are comparing how cheetahs and greyhounds runMiss Hudson said: "Greyhounds are artificially bred by us to be fast, whereas these [cats] have evolved for that.

"But cheetahs can run much faster than a racing greyhound.

"So we're trying to get them running at similar speeds to see what they do that's the same and what they do that makes them go that little bit faster."

In speedy humans - the fastest on record being Usain Bolt who ran 100m in 9.69 seconds (an average of 37km/h or 23mph) - speed is thought to be constrained by leg strength.

While in greyhounds, speed is believed to be limited by how quickly the dogs can swing its legs.

But for cheetahs - the reasons are still unclear - so the data from the experiments will be used to examine the forces and dynamics of the cats' legs, their speed, the length of each stride, as well as joint angles and posture.

Miss Hudson added: "We really don't know what it is about cheetahs that make them run so fast - it might be their flexible spines, or it might be their shoulder blades, it could be that they stretch their legs a bit more, but hopefully the data will unravel some of those mysteries."

Wild catsAlthough cheetahs' speedy reputation is well documented, there is still a question mark hanging over the top speeds that one can reach.

In 1997, a paper published in the Journal of Zoology gave the figure at 104km/h (64mph). The data came from an experiment that took place in Kenya in 1965, where a captive cheetah was timed as it chased the remains of a Sunday lunch attached to the back of a 4x4 vehicle.

So far the captive cheetahs are reaching top speeds of 54km/h

So far the captive cheetahs are reaching top speeds of 54km/h But researchers think it is very likely that the cats can run even faster than this.

Professor Wilson, whose biomechanics research is funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, said that the captive cheetahs at Whipsnade were so far reaching 54km/h (34mph).

He explained: "We know that cheetahs won't reach their full speed here. We hope they'll get to as fast as our racing greyhounds do, and we hope to get to a bigger space to do this."

The team also hopes to study cheetahs in the wild - where they would like to look at how wild cats run and also attempt to record a more accurate top speed.

Professor Wilson said: "Eventually we'd love to be able to get GPS and video data from cheetahs in the wild that are out and hunting - this is where they will be at the limits of their performance."

The team hopes to study the cheetahs in a larger enclosurenews.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8137962.stm

The team hopes to study the cheetahs in a larger enclosurenews.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8137962.stm________________________________________________________

Cheetah sets world speed recordBy John Johnston • jjohnston@enquirer.com • September 9, 2009

Sarah, an 8-year-old Cincinnati Zoo cheetah, succeeded Wednesday in setting the world speed record for land mammals.

Sarah, an 8-year-old Cincinnati Zoo cheetah, succeeded Wednesday in setting the world speed record for land mammals.Sarah covered 100 meters in 6.13 seconds at the zooÂ’s Regional Cheetah Breeding Facility, also known as the Mast Farm, in Clermont County. It was her second run of the day. In her first try, she ran 100 meters in 6.16 seconds. The record had been 6.19 seconds.

The zoo announced in July that the record attempt would pit Sarah against Zaza, an 8-year-old female cheetah at Cheetah Outreach in South Africa.

ZazaÂ’s Aug. 15 run in South Africa was postponed because bad weather caused a muddy track. SheÂ’s expected to run in late September or early October.

SarahÂ’s run initially was planned for Kentucky Speedway, but her handlers moved the run to her training facility because sheÂ’s most comfortable there and they felt sheÂ’d have a better chance of setting the record.

The course was certified by the Road Running Technical Council of USA Track & Field.

The world speed record attempts are meant to draw attention to the plight of cheetahs. The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the species as threatened, the risk level just below endangered. The worldwide cheetah population is estimated at fewer than 10,000.

Cheetahs are the worldÂ’s fastest land mammals, capable of reaching speeds up to 70 mph over short distances. In its natural habitat, the African savanna, it uses that speed to chase down prey.

In comparison, humans are a rather plodding species, at least when it comes to sprints. JamaicaÂ’s Usain Bolt holds the 100-meter record with a time of 9.58 seconds, which he set last month at the world championships.

The zooÂ’s Cheetah Encounter exhibit puts the catsÂ’ running ability on display at 11 a.m. and noon on Saturdays and Sundays through Oct. 4.

In 2000, a Cincinnati Zoo cheetah named Moya set the world speed record for land mammals, covering 100 meters in 6.60 seconds. Moya, who came from Cheetah Outreach, died in January.

MoyaÂ’s brother, Nyana, who lives in South Africa, broke that record in 2001 with a time of 6.19 seconds.

news.cincinnati.com/article/20090909/NEWS01/309080011__________________________________________________________

Epic cheetah hunt filmed in HDBy Matt Walker

Editor, Earth News

Page last updated at 08:11 GMT, Monday, 12 October 2009 09:11 UK

One band of brothers has developed a taste for ostrich

One band of brothers has developed a taste for ostrichStunning footage has been captured of three cheetahs cooperating to hunt and bring down an adult ostrich.

The high-definition (HD) film of the hunt was recorded by a BBC crew for the natural history series Life.

The behaviour could be unique among cheetahs, which are usually too slight to bring down such a formidable foe.

However, the three cheetahs, thought to be a band of brothers, have learnt how to routinely hunt this largest of birds.

Life producer Mr Adam Chapman describes how the film crew captured the cheetahs behaving in such a striking behaviour on camera.

"It's in a place called the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy in Kenya. The main bit of Lewa is about 60 square miles, it's huge. Basically the wildlife comes and goes off it."

Ten years ago, three male cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) arrived in the area, which they soon made their territory.

Male cheetahs often form collations to defend a good hunting area and gain better access to females.

But while cheetahs are incredibly fast, they are so slight that even coalitions usually only attempt to hunt animals that a single male can bring down.

Male cheetahs will often team up when hunting

Male cheetahs will often team up when huntingHowever, these three brothers have learnt to hunt cooperatively, Mr Chapman explains.

"They are amazing on what they will take on," he says.

While researching and filming for Life, Chapman and his colleagues saw the cheetahs hunting the calves of common eland, one of the largest antelope in Africa.

"If they got really lucky they'd succeed, and if they got unlucky they'd get beaten up by the adult eland or chased off."

The team also saw the cats hunting injured oryx, which sport long sharp horns over 1m long.

"One of them was quite lucky not get skewered in the process. The cheetah are pretty cock sure. They chance their arm. And that's probably how they came to start taking ostriches routinely. By one of them giving it a go."

The epic ostrich hunt was filmed in high-definition (HD) by BBC wildlife cameraman and presenter Simon King, who captured the event early one evening, after tracking the cheetahs for most of the day.

In the film, the three cheetahs can be seen stalking a male ostrich and giving chase, before breaking off midway to hunt an unsuspecting female ostrich instead.

One male cheetah jumps on the female ostrich's back, before the two other brothers join in to wrestle the huge bird to the ground.

"An ostrich is big enough and strong enough to actually run with the cheetah on its back," says Mr Chapman. "These three are hunting prey that it really takes their combined effort to pull down."

"There are a lot of cheetah in Africa, but however long I've been interested in these things, I've never heard of it before and I've certainly never seen it."

"What is special about it is they do it routinely, and they do it together."

The film crew say there is anecdotal evidence that the cheetahs may hunt in phase with the full moon, as it offers the best light at night.

The behaviour of the three cheetahs is so unique that it will likely die out with this particular band of brothers.

"When one of them pegs it and they are forced to stop doing it, that's it. There won't be another generation of Lewa cheetah hunting ostriches," says Mr Chapman.

The BBC series Life is broadcast at 2100BST on BBC One each week from Monday 12th October.

news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_8302000/8302054.stm__________________________________________________________

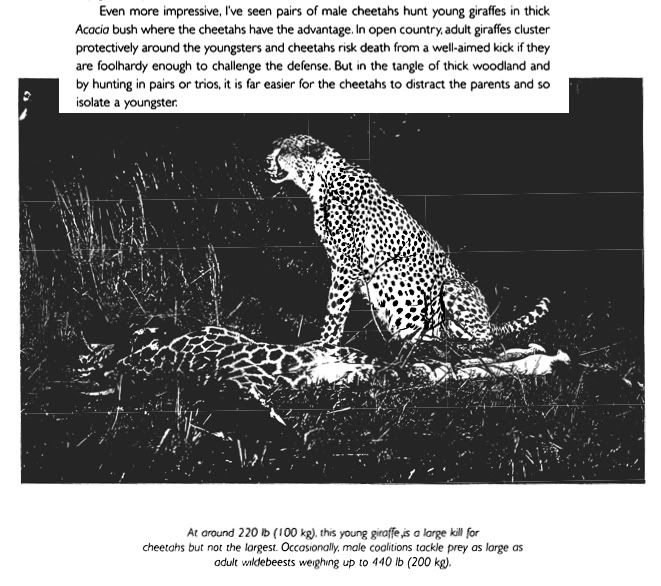

Cheetah prey and hunting success rate Kgalagadi Cheetah Project www.tllf.org.za/cheetahs/report4.htmlCheetah with Gemsbok kill

www.tllf.org.za/cheetahs/report4.htmlCheetah with Gemsbok kill Camel Killed by Cheetah

Camel Killed by Cheetah

_______________________________________________________

OP'ed by Pars

ASIATIC CHEETAHIn IranA report on Iranian or Asiatic Cheetah

wildlife.ir/English/Library/Farhadinia_MiandashtCheetahReport_Iran2007.pdfAccording to the reports of local people, Cheetahs kill young camel in Iran too.

"Claims of cheetahs killing young camel, sheep, and goat are rife among the shepherds inside the species habitat throughout the country; however, there was no evidence to approve it (B. Najafi, Jourabchian, and A. Karimi, pers.comm,). Two cheetah scats (FIG.18) as well as a few reports of livestock attack which was

verified by us are considered to be the first reliable evidences of cheetah depredation on livestock in the country."

On page 33 you will see a picture of red fox preyed by Asiatic Cheetah. Baby and Juvenile Boars, Sand Cats are said to be potential prey items in this report.

From wikipedia:

In Iran, the diet of the Asiatic Cheetah consists mainly of Jebeer Gazelle (also called Chinkara), Goitered Gazelle, wild sheep, Wild Goat, and Cape Hare. The Asiatic CheetahÂ’s range is restricted to the Central Iranian plateau. The main threat to the species is loss of their primary prey species, Jebeer gazelle, goitered gazelle, urial sheep, and wild goat, due to poaching and grazing competition with domestic livestock. Habitat loss from mining development and poaching of Asiatic Cheetahs also threaten their populations in Iran. "Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS)" and the "Department of Environment, Iran (DoE)" have started a collaring project for Asiatic Cheetahs in the fall of 2006.

In Iran Urial (Ovis orientalis) and wild goat (Capra aegagrus) appear to form the cheetahÂ’s primary prey today but both species inhabit mainly foothills or mountain slopes, habitats that are difficult for cheetahs to hunt.

In Central AsiaAn article on Asiatic Cheetah in Central Asia:

www.catsg.org/cheetah/05_library/5_3_publications/M/Mallon_2007_History_of_cheetahs_in_Central_Asia.pdf"Few details of the ecology and biology of Central Asian cheetahs are known. The main prey species was goitered gazelle Gazella subgutturosa which was formerly widespread and numerous across the region. Other prey species recorded include wild sheep or urial Ovis orientalis, young kulan Equus hemionus, saiga Saiga tatarica, hares Lepus tolai, porcupine Hystrix indica, small rodents, and birds such as sandgrouse Pterocles spp. (Bannikov 1984, Gvozdev 1989, Heptner & Sludskii 1972, Sadykov 1988). Cheetahs rarely preyed on domestic animals and were not considered a threat to livestock."

In IndiaFrom Wikipedia:

In India fifty years ago, prey was abundant, and it fed on the Blackbuck, the Chinkara, and sometimes the Chital and the Nilgai.

...is in low, isolated, rocky hills, near the plains on which live antelopes, its principal prey. It also kills gazelles, nilgai, and, doubtless, occasionally deer and other animals. Instances also occur of sheep and goats being carried off by it, but it

rarely molests domestic animals, and has not been known to attack men. Its mode of capturing its prey is to stalk up to within a moderate distance of between one to two hundred yards, taking advantage of inequalities of the ground, bushes, or other cover, and then to make a rush. Its speed for a short distance is remarkable far exceeding that of any other beast of prey, even of a greyhound or kangaroo-hound, for no dog can at first overtake an Indian antelope or a gazelle, either of which is quickly run down by C. jubatus, if the start does not exceed about two hundred yards. General McMaster saw a very fine hunting-leopard catch a black buck that had about that start within four hundred yards. It is probable that for a short distance the hunting-leopard is the swiftest of all mammals.

—Blanford writing on the Asiatic Cheetah in India quoted by Lydekker

an artcile on hunting with the help of cheetah:

www.catsg.org/cheetah/05_library/5_3_publications/D/Dharmakumarsinhji_1992_Cheetah_hunting.pdfAbout India's intention to reintroduce Cheetah. But which is astonishing is they are planning to reintroduce Namibian Cheetah instead of Asiatic cheetahs from Iran:

news.mongabay.com/2009/0709-cheetah_india.htmland latest developments about this project:

ibnlive.in.com/news/state-govts-reluctant-to-bring-the-cheetah-to-india/101109-3.html_____________________________________________________________

Elusive Saharan Cheetah Captured in PhotosBy Jeanna Bryner, LiveScience Managing Editor

posted: 24 December 2010 08:17 am ET

A hind image showing the Saharan cheetah in the Termit region of Niger, Africa, was captured recently by a camera trap. Credit: Sahara Conservation Fund/WildCRU.

Full Size 3 of 3

A camera trap recently captured the elusive Saharan cheetah in a vast desert in Niger, Africa.

A camera trap recently captured the elusive Saharan cheetah in a vast desert in Niger, Africa.An elusive Saharan cheetah recently came into the spotlight in Niger, Africa, where a hidden camera snapped photos of the ghostly cat, whose pale coat and emaciated appearance distinguish it from other cheetahs.

In one of the images the sleek, light-colored cat with small spots on its coat and a small head is turning in the direction of the camera, its eyes aglow.

Its appearance, and how the Saharan cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus hecki) is genetically related to other cheetahs is open to question, said John Newby, CEO of the Sahara Conservation Fund (SCF), who is part of the team, along with SCF's Thomas Rabeil and others, who captured the camera-trap snapshots between July ad August. What they know about this species comes from the few photos they've managed to capture.

"I think we were more happy than surprised when the images turned up, because we knew cheetahs were in the general area because we had seen their tracks on several occasions," Newby said. "However, the area is so vast that picking up an animal as rare as this always entails a lot of luck and good judgment on where to place the cameras."

The animal is so rare and elusive scientists aren't sure how many even exist, though they estimate from the few observations they've made of the animal and tracks that fewer than 10 individuals call the vast desert of Termit and Tin Toumma in Niger home. Fewer than 200 cheetahs probably exist in the entire Sahara.

Losing this cheetah would also mean losing important genetic and biological diversity, as these animals have adaptations for survival in extreme desert conditions.

Their home can reach sizzling temperatures up to 113 degrees Fahrenheit (45 degrees Celsius), and is so parched no standing water exists. "They probably satisfy their water requirements through the moisture in their prey, and on having extremely effective physiological and behavioral adaptations," Newby said.

In an effort to conserve water and stay out of the heat, the Saharan cheetah is even more nocturnal than other cheetahs.

Spotting these cats in the wild has been a challenge. "They are incredibly shy and elusive animals," Newby said. In addition, they likely have broad home ranges since their prey – gazelles, hares, large birds and smaller rodents – are relatively scarce. Observations that have been made suggest they prefer caves and rock shelters as breeding dens.

Among the threats to the pale cat are scarcity of prey due to poaching and overuse, and conflicts with herders over stock harassment and killing of their animals, according to SCF. Apparently cheetah skins are prized as prayer rugs or used to make slippers.

"They are suspected of taking goats and even baby camels, and as a result are persecuted just like most other large predators," Newby said. "Work underway with local nomads is putting together the true picture of livestock predation in an attempt to reduce the arbitrary slaughter of carnivores that has massively reduced populations of cheetah and striped hyenas."

Newby and Rabeil say the camera-trap study will provide tangible evidence for the cheetah's existence in the Termit area.

"The more we know about the animal the better we can conserve it, including pinpointing key areas for extra protection," Newby said. "The cheetahÂ’s presence adds weight to arguments for the entire zoneÂ’s protection as a nature reserve and strengthens our ability to raise support for conservation activities."

The Saharan cheetah is listed as critically endangered on the 2009 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (IUCN stands for International Union for Conservation of Nature.)

www.livescience.com/animals/saharan-cheetah-photo-niger-africa-101224.html________________________________________________________

Iran's endangered cheetahs are a unique subspeciesBy Ella Davies

Earth News reporter

Page last updated at 09:19 GMT, Monday, 24 January 2011

Acinonyx jubatus venaticus

Acinonyx jubatus venaticus

Iran's critically endangered cheetahs are the last remaining survivors of a unique, ancient Asian subspecies, genetics experts reveal.

New analysis confirms Iran's cheetahs belong to the subspecies Acinonyx jubatus venaticus.

DNA comparisons show that these Asiatic cheetahs split from other cheetahs, which live in Africa, 30,000 years ago.

Researchers suggest that Iran's cheetahs must be conserved to protect the future of all cheetahs.

Cheetahs formerly existed in 44 countries in Africa but are now only found in 29.

Historically, they were also recorded across southwest and central Asia but can now only be found in Iran.

Scientists have previously said that cheetahs have low genetic variability, theorising that a "population crash" approximately 10,000 years ago led to inbreeding in the species.

Despite this, five 'different' subspecies are currently described according to where they live.

Genetic studies in the 1990s confirmed cheetahs found in southern Africa (A. j. jubatus) and east Africa (A. j. raineyi) as separate subspecies.

However, it has not been clear whether populations in west Africa (A. j. hecki), northern-east Africa (A. j. soemmeringii), and north Africa and Iran (A. j. venaticus) are genetically different enough to deserve their current status as subspecies.

Aiming to solve the puzzle of modern cheetahs' origins, scientists from the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna, Austria have been working in collaboration with the Iranian Department of Environment and wildcat conservation group Panthera.

Dr Pamela Burger and her team analysed the DNA of cheetahs from a wide geographical and historical range, including medieval remains found in north-western Iran.

"With our data we prove that current Iranian cheetahs represent the historical Asiatic subspecies A.j. venaticus as they share a similar genetic profile with specimen originating from northwestern Iran in 800-900 CE," explains Dr Burger.

The researchers have also been able to distinguish Iranian cheetahs from their nearest neighbours in northern-east Africa which were confirmed as A. j. soemmeringii.

Cheetahs in north Africa, previously considered the same subspecies as those in Iran, were actually found to have more in common genetically with those in west Africa.

By comparing sequences in the DNA, researchers have found that the unique Asiatic cheetahs separated from the rest of the species in southern Africa over 30,000 years ago.

Dr Burger explains that because this split occurred long before the theorised population crash, A.j. venaticus represents a highly distinct lineage.

"The implications of our discovery are that the confirmation of the subspecies is a basis for future conservation management. If the aim is to conserve this biodiversity, subspecies should not be mixed," she says.

Currently estimated at just 60-100 individuals with less than half at mature breeding age, the Iranian cheetah population is classified as critically endangered by the IUCN Red List.

Together with the United Nations Development Programme, Panthera and the Wildlife Conservation Society the Iranian Department of the Environment has established a programme to make conservation of the Asiatic cheetah a national priority.

Conservationists are concerned that time is running out for Iran's cheetahs.

"We have been successful in stabilising numbers in Iran but we still have a long way to go before we can consider this unique sub-species secure," says Alireza Jourabchian, Director of the Conservation of the Asiatic Cheetah Programme (CACP) in Iran.

Threats facing the small population include overhunting of cheetah prey, habitat degradation and direct poaching.

news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_9365000/9365567.stm__________________________________________________________

From Dexterous

Although we all know that cheetahs do prefer impala, springbok, gerenuk and similar antelope, look at this picture of a male cheetah with what it appears to be an adult zebra

___________________________________________________________

From Sicilianu :

White Cheetah

The site io9 has ended their “Cryptid Summer” contest with a winner. The pick was an entry with some rather striking photographs of a White Cheetah in Africa.

The prize of $2000 was won by Guy Combs, who chased down the rare White Cheetah. The panel of expert judges “included Mark Siddall, a zoologist who specializes in leeches at the American Museum of Natural History in New York; Loren Coleman, a widely-recognized expert in cryptozoology and creator of the International Cryptozoology Museum in Maine; photoshop expert and designer Paul Hogan (also known as Garrison Dean, viral video creator extraordinaire); along with io9 editors Charlie Jane Anders and…Annalee Newitz.”

Yes, I was on the panel and felt that the White Cheetah might be a good cryptid choice. Within cryptozoology, there has been some focus in the recent past on the quest for the “King Cheetah,” although it turned out to be a pattern mutation.

White cheetahs have been sighted and discussed since, at least, 1608*. I could see some expeditions out to discover if this new find is a part-albino or a new subspecies of the known cheetah. Of course, it is a real cryptid, an unknown, as yet unverified species, due to the fact it has not been captured, alive or dead, in a modern situation where DNA has been taken, to note one of many criteria. This cat could be one of many things, perhaps, but the speculation is that it is a form of cheetah, naturally. Since we technically do not know what it is, it is a cryptid. (For those still confused, specifically, by what is and isn’t a cryptid, please see what I have written previously on “cryptoterms.”)

Let me share the remarkable photographs submitted of this mystery cat:

See more details here at the io9 site.

Following are the words of the photographer, Guy Combs, who took the images:

Back in December [2010] I was told about this incredible ‘morph’ phenomenon that has not been seen for over 90 years, and that there was a pressing need to monitor and protect it while raising awareness of the species as a whole. The last one recorded was shot in Tanzania in 1921. By ‘morph’ this means a genetic colour variation, the most well known being the ‘King’ cheetah, specimens of which have only occurred in South Africa and Zimbabwe. The Mughal Emperor of India recorded having a white cheetah presented to him in 1608, saying that the spots were of a blue colour and the whiteness of the body also inclined to blue-ishness. This suggests a chinchilla mutation which restricts the amount of pigment on the hair shaft. Red cheetahs have dark tawny spots on a golden background and some desert cheetahs are very pale to be more camouflaged in their environment. There are also reported cases of melanism or albinism, but the latter does not apply to this cheetah. The only reported cases of this morph which scientists believe is a recessive gene like the king cheetah, have been in East Africa from the subspecies, acynonix jubatus raineyii.

I was hooked from the first moment I heard about this, and needless to say I immediately wanted to get reference, but the prospect of finding it seemed incredibly remote. The only hope I had was that the cheetah, a male, was still with his mother and occupying the same area before he reached the age of independence. This time was fast approaching so the need was urgent to find him. Apparently he already showed small signs of conflict with other male cheetahs trying to get to his mother who had come into season again. Here is an account of my search:

I was at home at Soysambu when I got the call that a window of time was open for me to have a vehicle and a spotter plane available to search the 100,000 acre area in which the cheetah was believed to be. ThatÂ’s quite literally the equivalent of a needle in a haystack. So I made my way there there with not a great deal of optimism other than I thought I would get some good background reference.

Our first search was in a plane made by the Israeli army to train pilots and coincidentally called a Cheetah: a small frame of aluminium poles and nylon fabric with a propeller and wheels. I confess to having raised anxiety levels when on small aircraft due to a couple of infamous past experiences, so I wasnÂ’t thoroughly enthused when the pilot (despite being one of the finest in Kenya), explained that we would be doing an hour of mostly low level flying with tight turns. There were two big storms on either side and the air was being moved rapidly between them so we spent most of the flight going sideways. I gritted my teeth and tried to concentrate on searching the ground but it was pretty much a pointless excersise.

So back on the ground I set off in a landrover to search the area, most of which has no roads and at least managed to get some good background reference in the evening light. I figured that I could probably work this one with photographs someone had taken of him as a much younger cub and reference I had of adult male cheetahs. After all, he was just the same but with no spots, right? So I headed to town and met some friends for a few drinks. Then my phone rang:

- “We’ve just found him!!!”

- “did you get any pictures?”

- “no sorry didn’t have a camera”

- “ok I will be up and out there at sparrows!”.

My host was there warming up the plane and getting ready, however I suggested I trade places with someone in one of the vehicles so that at least if he was found I would be able to get some good ground shots. We set off and watched as the plane traversed from one end of the horizon to the other trying our best to follow, but silence on the radio. By mid-morning we once again had to call it off and regroup for coffee. Everyone dispersed and I caught up with some sleep. Pretty much the same thing that evening, and I was beginning to lose hope. Cheetah can cover huge distances at night but usually stay in the same area during the day, and by the following morning two nights had passed. My only hope was that because he was with his mother, that they were still occupying the same area.

Once again, eternally optimistic, my host set off in the plane with another hapless volunteer that had to take my place – I felt like such a lightweight. Turns out that I made 100% the best decision I could have. As we were thundering over the roadless plain in the landrover, I suddenly noticed that the plane had started to circle. My heart shifted into first gear. Our radio was out but the plane had unmistakably made several tight turns and was continuing to do so until we managed to get close to the circle it was making. Of course it happened to be an area covered in large rocks and low trees, so I was sitting forward in my seat, clinging to the dash with my face up against the windshield trying to keep my camera on my lap as we bounced ridiculously over huge boulders.

Then there he was. A white spot in a landscape painted gold by the morning sun. As we got closer we had to be very tactical about our speed and noise level which is pretty much impossible in a landrover, especially when you’re driving over big rocks. Lots of “ok forwards…”, “STOP” and “shhhhhhh!!!” in theatrical whisper. He let us get quite close before hunkering down and slinking off in the direction of even more vehicle-unfriendly rocks. But we managed to keep up and he didn’t seem overly anxious about us. We barely noticed that his mother was following at a distance. We were with him like this for about 30 minutes that seemed like about 5 seconds. Then having punished the vehicle to the extent that I was amazed the wheels were still on, I noticed that he began to move away from us, walking at first, then trotting, then a good run. My heart sank and I thought my last view would be him running away in fear, but it became quickly apparent that he was focusing on something. The sun was in my eyes but I could make out a dark shape moving fast in a perpendicular direction to him. Binoculars out – it was a Serval Cat!!! Next thing we knew he was running at full tilt after this thing, zigzagging first then long stretches of blindingly fast speed. Alas, we were in the worst part of the boulder field and there was clearly no option of a pursuit. So after he disappeared and the dust settled we looked at each other and let out a looooong sigh. Amazing.

I came away feeling as though I had seen Bigfoot or the Loch Ness Monster. And got photographs!!! This is not my first involvement with cheetahs. IÂ’m very familiar with the species in terms of the personal friendships I have with people who work tirelessly to ensure their survival, and the subject matter I have been asked to paint. From my childhood I will never forget visiting some friends of my parents in Naivasha who had a pair of domesticated cheetah. Oblivious to their presence I ignored a well intentioned warning and took off down their garden, very quickly finding myself face down in the grass with a cheetah on my back. Fortunately my Dad, a well rehearsed rugby player, dealt with my assailant quickly and efficiently. However, at no point did I feel as though my life was in danger. It was just like being roughed up by a playful dog. So in a way I have always felt a strong connection with them, and I am now practically obsessed with this individual animal and the unforgettable experience of finding him and being allowed to spend half an hour or so with him. I hope I have done him justice on canvas.

The painting itself, aside from being the most accurate portrayal I was capable of, includes certain elements that are important to the story. The area is one that accommodates one of the highest densities of cheetah populations in East Africa. This could be as a result of a distinct lack of other larger predators that would be a threat to their existence, a large prey base, and an area relatively protected from development. I wanted to include this latter factor and have faintly suggested a settlement complete with cell phone tower on the ridge in the middle distance. This, of course, is the greatest problem that cheetahs face in our ‘human’ age. The locations is very significant here also, and the distant Ngong Hills together with the setting full moon make it very specific. The sun and moon are intentionally symbolic here too: the moon representing Artemis, the goddess of animals and forests and the sun representing Apollo, the god of arts, amongst other things. The title, “The Phantom”, suggests an elusive, mythical entity that exists somewhere between night and day.

Guy Combs

++++

*The Historical White Cheetah

The Mughal Emperor of India, Jahangir, recorded having a white cheetah presented to him in 1608.

In the memories of Tuzk-e-Jahangiri, the Emperor, says that in the third year of his reign:

Raja Bir Singh Deo brought a white cheetah to show me. Although other sorts of creatures, both birds and beasts have white varieties Â…. I had never seen a white cheetah. Its spots, which are (usually) black, were of a blue colour, and the whiteness of the body also inclined to blue-ishness.

Tuzk-e-Jahangiri

This suggests a chinchilla mutation which restricts the amount of pigment on the hair shaft. Although the spots were formed of black pigment, the less dense pigmentation gives a hazy, grayish effect. As well as Jahangir’s white cheetah at Agra, a report of “incipient albinism” has come from Beaufort West, according to CAW Guggisberg (1975) “Cheetah, Hunting Leopard – Wild Cats of the World,” in his Wild Cats of the World, London: David & Charles, Newton Abbot, pp. 266- 289.

_____________________________________________________________

From Reddhole

Sexual dimorphism is quite strong among cheetahs and is an adaptation to both killing larger prey and male intraspecific competition for breeding rights. The following study shows male cheetahs exhibit significant sexual dimorphism vs. females:

Source: MORPHOLOGY, PHYSICAL CONDITION, AND GROWTH OF THE CHEETAH (ACINONYX JUBATUS JUBATUS) Journal of Mammalogy, Marker and Dickman, 84(3):840–850, 2003Information regarding morphology of wild cheetahs is scant, and even where data exist they rarely were collected using a standardized methodology. We used a consistent technique to examine 241 wild Namibian cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus jubatus) to study morphology, sexual dimorphism, growth rates, and physical condition and to investigate how these data compared with those in previous studies. Significant sexual dimorphism was evident for all measurements. The majority of cheetahs were in excellent condition at the time of examination, although old cheetahs and those that had been held captive for more than a month were in significantly poorer condition.Male cheetah coalitions kill significantly larger prey than females. In fact, the prey is on average larger than leopard prey (male and female average). For example, in the study below male cheetah prey averaged more than 65 kg with a third weighing more than 100 kg. By contrast, the average weight of leopard prey is typically less than 50 kg.

Source: Charlene Bissett, Masters of Science Thesis: THE FEEDING ECOLOGY, HABITAT SELECTION ANDHUNTING BEHAVIOUR OF RE-INTRODUCED CHEETAH ON

KWANDWE PRIVATE GAME RESERVE, EASTERN CAPE

PROVINCE

Howeverthedifferent cheetah groups on Kwandwe killed different sized prey. There is some controversy over the extent to which coalitions of cheetah hunt cooperatively (Eaton 1970; Kruuk & Turner 1967; Caro 1994). However, on Kwandwe, the

three male coalition accompanied one another on all hunts and actively co-operated in the hunts. On a number of occasions the cheetah drove prey toward concealed coalition partners

(pers. obs).

Theco-operation in hunting by the three adult male coalition on Kwandwe enabled them to kill large prey (>65kg), and this has been reported in some previous studies

(Caro 1994; Hunter 1998; Mills 1998; Mills et al. 2004). Male coalitions need a greater biomass of food per unit time than solitary cheetah (Caro 1994) and this need could be met by

making more frequent kills or by killing larger prey. It has been suggested that large carnivores will resist changing kill frequency and that changes in group size are associated

with change in the size of the prey (Caro 1994) and this appears to be the pattern at Kwandwe.

More than a third of kills made by the coalition weighed more than a 100kg and in most cases the cheetah remained at their kills until they were satiated. However, the continuous observations on the coalition showed that the cheetah did adjust the kill rate to meet their energetic needs as they killed twice on the same day on more than one occasion. Significantly, on these occasions the kills were juveniles which would explain the need to increase the kill rate. Females with cubs preyed on more medium sized animals than single females and again this can be explained in terms of the increased needs of the group over a solitary female.

However, unlike the coalition the adult females and their cubs do not have the power to kill large prey.________________________________________________________

Spotless cheetah snapped in the wild

Photographer reveals pictures of rare big cat with a sandy golden coat and brown freckles instead of dark spotsSteven Morris and agency

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 25 April 2012 17.59 BST

Article history

A spotless adult cheetah at the Athi Kapiti Conservancy in Kenya – the sighting is thought to be first in almost a century.

A spotless adult cheetah at the Athi Kapiti Conservancy in Kenya – the sighting is thought to be first in almost a century.A rare 'spotless' cheetah has been photographed in Kenya by wildlife photographer Guy Combes, who got within around 50m of the big cat.

Combes, originally from Dorset but now based in California, had heard tale of the spotless leopard and travelled to the Athi Kapiti Conservancy in search of it but gave up after days of fruitless searching.

"I didn't think it likely that we would find the cheetah and went back to Nairobi. I then got a call saying it had been seen again so I spent another two days searching," he said. Eventually he spotted the animal.

"I was really excited as we managed to get about 50 yards away. It was was a staggeringly beautiful animal. I didn't expect to see it at all, the area we were going to search was 100,000 acres without borders and it could have easily been beyond that."

John Pullen, curator of mammals at Marwell Wildlife in Hampshire, who has examined the photographs, described the sighting as "quite rare". He said: "There are some spots still evident over the back area but most are missing. The spots or markings on all wild cats are in fact the skin colour and the hair growing from that part of the skin takes on the colouration, so if you shaved off the hair the pattern would be the same. This is really like a rare skin issue where something has happened to the genetic coding that would give the normal pattern."

Combes captured the images last year but has shown it now after photographs of a strawberry-coloured leopard photographed in South Africa emerged. It also comes as footage and images of a white killer whale spotted off the eastern coast of Russia surfaced.

www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/apr/25/spotless-cheetah-pictures-wild?newsfeed=true