Post by theropod on Jul 10, 2015 20:54:19 GMT 5

Deinocheirus mirificus is an ornithomimosaurian coelurosaur from the Campanian-Maastrichtian Nemegt Formation.

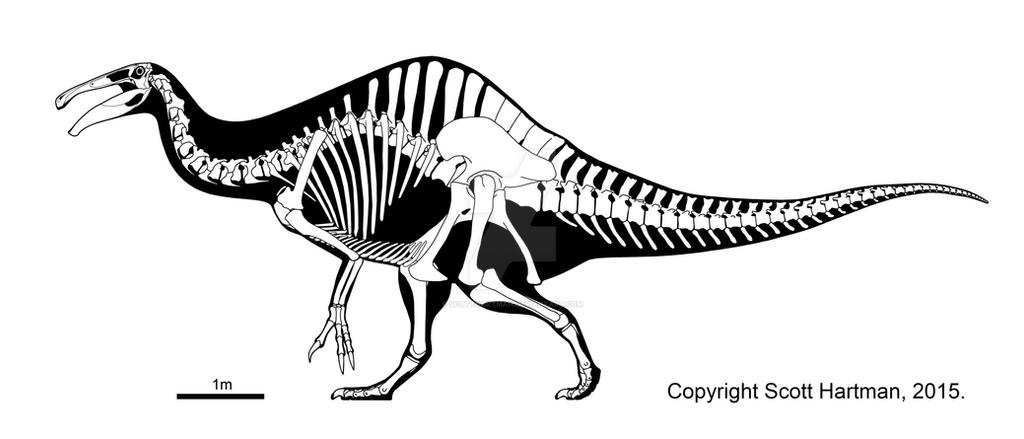

Skeletal reconstruction by Scott Hartman, from here: www.deviantart.com/art/Deinocheirus-an-odd-duck-545188992

Material:

Holotype, MPC-D 100/18 (formerly ZPal MgD-I/6), material from forelimbs and shoulder girdle (scapulocoracoids 1530mm, humerus 938mm, ulna 688mm, radius 630mm, manus 770mm) with associated rib, vertebral and gastralial fragments (Osmólska & Roniewicz 1970)

referred specimens:

• MPC-D 100/127 (subcomplete skeleton lacking right forelimb and parts of post-cervical axial skeleton; 106% the size of holotype; skull 1024mm pmx-occ [1062mm max], humerus 1000mm, ulna 670mm, radius 655mm, ilium 1330mm, femur 1320mm, tibia 1160mm, Lee et al. 2014)

• MPC-D 100/128 (partial skeleton including partial post-cervical vertebral collumn and pelvic and hindlimb elements; 74% the size of MPC-D 100/127; ilium 900mm, femur 980mm, tibia e845mm, Lee et al. 2014)

• MPC-D 100/126 (gastralial fragments, Bell et al. 2012)

Locality & Horizon:

Nemegt Basin, Gobi Desert, Campanian-Maastrichtian, seasonally wet fluvial inland environment (Bell et al. 2012, PalaeoDB):

• Altan Ula Ill (Type locality, Osmólska & Roniewicz 1970)

• Bugiin Tsav, Altan Uul IV (Lee et al. 2014)

Anatomy & Palaeobiology:

Being initially known from little more than a giant pair of forelimbs and some fragments, much of the anatomy of D. mirificus was shrouded in mystery for over four decades. However, from the size of the holotypic material it could be concluded that the taxon was one of the biggest theropod dinosaurs (Osmólska & Roniewicz 1970), sometimes thought of as the only real rival for the largest tyrannosaurs until the discovery of Giganotosaurus (Coria & Salgado 1995) and subsequent confirmation of giant carcharodontosaurs and spinosaurs. New skeletal material corroborates its status as one of the biggest theropods, with many of its skeletal measurements being among the largest reported within theropoda (cf. Lee et al. 2014, Brochu 2003, Canale et al. 2015).

Being by far the biggest ornithomimosaur (total length of 11.8m based on Hartman 2015 [online], body mass in excess of 6t according to Lee et al. 2014), many aspects of its anatomy differ from those of other members of the clade, largely as a consequence of allometric trends (Lee et al. 2014). Namely, its hindlimbs are more graviportal, with a femur longer than the tibia, and lack the arctometatarsal condition that is present in Ornithomimidae (Holtz 1994).

All vertebrae and parts of the pelvic girdle are pneumatised, making for a similarly extreme degree of pneumatisation as is found in sauropods. It’s dorsal vertebral collumn exhibits strong ventral curvature, resembling that of hadrosaurs (Hartman 2015 [online], Lee et al 2014). The dorsal and sacral neural spines are hypertrophied and reach up to 8.5 times centrum height (last dorsal vertebra), forming a tall dorsal superstructure that probably anchored supraspinal ligaments and (neck) musculature (Hartman 2015 [online]) and which could also have served for display (Lee et al. 2014).

The last caudal vertebrae are fused, forming a pygostyle resembling those found in Therizinosaurs and Oviraptorosaurs. Deinocheirus’ skull morphology is very peculiar and different from its relatives in that the rostrum is shallow and highly elongate, while the lower jaw is extremely deep and massive (resembling Spinosaurus and some mosasaurs). It is also the first ornithomimosaur for which a furcula is known (Lee et al. 2014).

It is implied that Deinocheirus was a relatively slow-moving animal. Edentulous, weakly muscled jaws, a ventrally displaced anterior end of the mandible, presence of rhamphotheca and indications of a strong tongue, as well as the discovery of gastroliths and fish remains in its stomach cavity suggests an omnivorous diet that included soft, supposedly aquatic plant matter and small aquatic animals that could have been caught of cropped with the beak and then sucked in (Lee et al. 2014).

Re-examination of the type locality resulted in the finding of two gastralia referred to Deinocheirus, bearing bite marks most consistent with the sympatric tyrannosaurid Tarbosaurus bataar, which probably resulted from post-mortem feeding on the specimen by the tyrannosauroid (Bell et al. 2012).

Phylogeny:

Originally classified as part of a basal lineage of "carnosaur" (Osmólska & Roniewicz 1970; note the obsolete use of the term "carnosaur" that was widespread during that time), it has been assigned to the Ornithomimosauria more recently (e.g. Makovicky et al. 2004), a finding subsequently corroborated by the discovery and recent description of new material, which supports the placement of Deinocheiridae as the sister taxon of Ornithomimidae within Ornithomimosauria (Lee et al. 2014).

–––References:

Bell, Phil R.; Currie, Philip J.; Lee, Yuong-Nam (2012): Tyrannosaur feeding traces on Deinocheirus (Theropoda:?Ornithomimosauria) remains from the Nemegt Formation (Late Cretaceous), Mongolia. Cretaceous Research, Vol. 37 pp. 186-190

Brochu, Christopher A. (2003): Osteology of Tyrannosaurus rex: Insights from a Nearly Complete Skeleton and High-Resolution Computed Tomographic Analysis of the Skull. Memoir (Society of Vertebrate Paleontology), Vol. 7 pp. 1-138

Canale, Juan I.; Novas, Fernando E.; Pol, Diego (2015): Osteology and phylogenetic relationships of Tyrannotitan chubutensis Novas, de Valais, Vickers-Rich and Rich, 2005 (Theropoda: Carcharodontosauridae) from the Lower Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina. Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology, Vol. 27 (1) pp. 1-32

Coria, Rodolpho A.; Salgado, Leonardo (1995): A new giant carnivorous dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Patagonia. Nature, Vol. 377 (6546) pp. 224-226

Holtz, Thomas R. (1994): The arctometatarsalian Pes, an Unusual Structure of the Metatarsus of Cretaceous Theropoda (Dinosauria: Saurischia). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol. 14 (4) pp. 480-519

Lee, Yuong-Nam; Barsbold, Rinchen; Currie, Philip J. ; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Lee, Hang-Jae; Godefroit, Pascal; Escuillié, François; Chinzorig, Tsogtbaatar; (2014): Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus. Nature, Vol. 515 (7526) pp. 257-260 (advance online publication: pp. 1-12) + Supplementary data

Makovicky, Peter J.; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Currie, Philip J. (2004): Ornithomimosauria. In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka: The Dinosauria. Berkeley pp. 137-150

Osmólska, Halszka; Roniewicz, Ewa (1970): Deinocheiridae, a new family of theropod dinosaurs. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, Vol. 21 pp. 5-19

Online:

Hartman, Scott (2015): Deinocheirus - Therizinosaur or hadrosaur mimic? www.skeletaldrawing.com/home/deinocheirus-therizinosaur-or-hadrosaur-mimic7102015 (accessed 10 July 2015 )

PaleoDB: Fossilworks: Altan Ula III, site 2. fossilworks.org/bridge.pl?a=collectionSearch&collection_no=38695 (accessed 10 July 2015)

PaleoDB: Fossilworks: Deinocheirus mirificus. fossilworks.org/bridge.pl?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=57246 (accessed 10 July 2015)

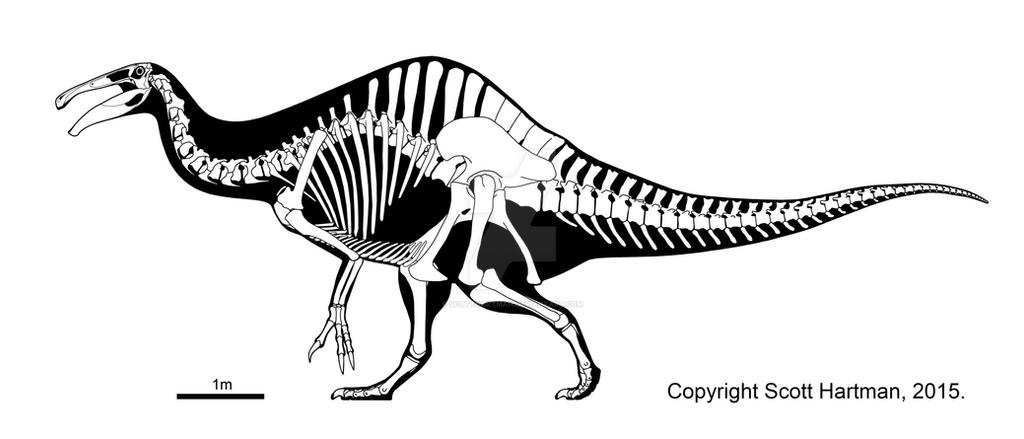

Skeletal reconstruction by Scott Hartman, from here: www.deviantart.com/art/Deinocheirus-an-odd-duck-545188992

Material:

Holotype, MPC-D 100/18 (formerly ZPal MgD-I/6), material from forelimbs and shoulder girdle (scapulocoracoids 1530mm, humerus 938mm, ulna 688mm, radius 630mm, manus 770mm) with associated rib, vertebral and gastralial fragments (Osmólska & Roniewicz 1970)

referred specimens:

• MPC-D 100/127 (subcomplete skeleton lacking right forelimb and parts of post-cervical axial skeleton; 106% the size of holotype; skull 1024mm pmx-occ [1062mm max], humerus 1000mm, ulna 670mm, radius 655mm, ilium 1330mm, femur 1320mm, tibia 1160mm, Lee et al. 2014)

• MPC-D 100/128 (partial skeleton including partial post-cervical vertebral collumn and pelvic and hindlimb elements; 74% the size of MPC-D 100/127; ilium 900mm, femur 980mm, tibia e845mm, Lee et al. 2014)

• MPC-D 100/126 (gastralial fragments, Bell et al. 2012)

Locality & Horizon:

Nemegt Basin, Gobi Desert, Campanian-Maastrichtian, seasonally wet fluvial inland environment (Bell et al. 2012, PalaeoDB):

• Altan Ula Ill (Type locality, Osmólska & Roniewicz 1970)

• Bugiin Tsav, Altan Uul IV (Lee et al. 2014)

Anatomy & Palaeobiology:

Being initially known from little more than a giant pair of forelimbs and some fragments, much of the anatomy of D. mirificus was shrouded in mystery for over four decades. However, from the size of the holotypic material it could be concluded that the taxon was one of the biggest theropod dinosaurs (Osmólska & Roniewicz 1970), sometimes thought of as the only real rival for the largest tyrannosaurs until the discovery of Giganotosaurus (Coria & Salgado 1995) and subsequent confirmation of giant carcharodontosaurs and spinosaurs. New skeletal material corroborates its status as one of the biggest theropods, with many of its skeletal measurements being among the largest reported within theropoda (cf. Lee et al. 2014, Brochu 2003, Canale et al. 2015).

Being by far the biggest ornithomimosaur (total length of 11.8m based on Hartman 2015 [online], body mass in excess of 6t according to Lee et al. 2014), many aspects of its anatomy differ from those of other members of the clade, largely as a consequence of allometric trends (Lee et al. 2014). Namely, its hindlimbs are more graviportal, with a femur longer than the tibia, and lack the arctometatarsal condition that is present in Ornithomimidae (Holtz 1994).

All vertebrae and parts of the pelvic girdle are pneumatised, making for a similarly extreme degree of pneumatisation as is found in sauropods. It’s dorsal vertebral collumn exhibits strong ventral curvature, resembling that of hadrosaurs (Hartman 2015 [online], Lee et al 2014). The dorsal and sacral neural spines are hypertrophied and reach up to 8.5 times centrum height (last dorsal vertebra), forming a tall dorsal superstructure that probably anchored supraspinal ligaments and (neck) musculature (Hartman 2015 [online]) and which could also have served for display (Lee et al. 2014).

The last caudal vertebrae are fused, forming a pygostyle resembling those found in Therizinosaurs and Oviraptorosaurs. Deinocheirus’ skull morphology is very peculiar and different from its relatives in that the rostrum is shallow and highly elongate, while the lower jaw is extremely deep and massive (resembling Spinosaurus and some mosasaurs). It is also the first ornithomimosaur for which a furcula is known (Lee et al. 2014).

It is implied that Deinocheirus was a relatively slow-moving animal. Edentulous, weakly muscled jaws, a ventrally displaced anterior end of the mandible, presence of rhamphotheca and indications of a strong tongue, as well as the discovery of gastroliths and fish remains in its stomach cavity suggests an omnivorous diet that included soft, supposedly aquatic plant matter and small aquatic animals that could have been caught of cropped with the beak and then sucked in (Lee et al. 2014).

Re-examination of the type locality resulted in the finding of two gastralia referred to Deinocheirus, bearing bite marks most consistent with the sympatric tyrannosaurid Tarbosaurus bataar, which probably resulted from post-mortem feeding on the specimen by the tyrannosauroid (Bell et al. 2012).

Phylogeny:

Originally classified as part of a basal lineage of "carnosaur" (Osmólska & Roniewicz 1970; note the obsolete use of the term "carnosaur" that was widespread during that time), it has been assigned to the Ornithomimosauria more recently (e.g. Makovicky et al. 2004), a finding subsequently corroborated by the discovery and recent description of new material, which supports the placement of Deinocheiridae as the sister taxon of Ornithomimidae within Ornithomimosauria (Lee et al. 2014).

–––References:

Bell, Phil R.; Currie, Philip J.; Lee, Yuong-Nam (2012): Tyrannosaur feeding traces on Deinocheirus (Theropoda:?Ornithomimosauria) remains from the Nemegt Formation (Late Cretaceous), Mongolia. Cretaceous Research, Vol. 37 pp. 186-190

Brochu, Christopher A. (2003): Osteology of Tyrannosaurus rex: Insights from a Nearly Complete Skeleton and High-Resolution Computed Tomographic Analysis of the Skull. Memoir (Society of Vertebrate Paleontology), Vol. 7 pp. 1-138

Canale, Juan I.; Novas, Fernando E.; Pol, Diego (2015): Osteology and phylogenetic relationships of Tyrannotitan chubutensis Novas, de Valais, Vickers-Rich and Rich, 2005 (Theropoda: Carcharodontosauridae) from the Lower Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina. Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology, Vol. 27 (1) pp. 1-32

Coria, Rodolpho A.; Salgado, Leonardo (1995): A new giant carnivorous dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Patagonia. Nature, Vol. 377 (6546) pp. 224-226

Holtz, Thomas R. (1994): The arctometatarsalian Pes, an Unusual Structure of the Metatarsus of Cretaceous Theropoda (Dinosauria: Saurischia). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Vol. 14 (4) pp. 480-519

Lee, Yuong-Nam; Barsbold, Rinchen; Currie, Philip J. ; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Lee, Hang-Jae; Godefroit, Pascal; Escuillié, François; Chinzorig, Tsogtbaatar; (2014): Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus. Nature, Vol. 515 (7526) pp. 257-260 (advance online publication: pp. 1-12) + Supplementary data

Makovicky, Peter J.; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Currie, Philip J. (2004): Ornithomimosauria. In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka: The Dinosauria. Berkeley pp. 137-150

Osmólska, Halszka; Roniewicz, Ewa (1970): Deinocheiridae, a new family of theropod dinosaurs. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, Vol. 21 pp. 5-19

Online:

Hartman, Scott (2015): Deinocheirus - Therizinosaur or hadrosaur mimic? www.skeletaldrawing.com/home/deinocheirus-therizinosaur-or-hadrosaur-mimic7102015 (accessed 10 July 2015 )

PaleoDB: Fossilworks: Altan Ula III, site 2. fossilworks.org/bridge.pl?a=collectionSearch&collection_no=38695 (accessed 10 July 2015)

PaleoDB: Fossilworks: Deinocheirus mirificus. fossilworks.org/bridge.pl?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=57246 (accessed 10 July 2015)