Post by Infinity Blade on Sept 5, 2015 22:29:41 GMT 5

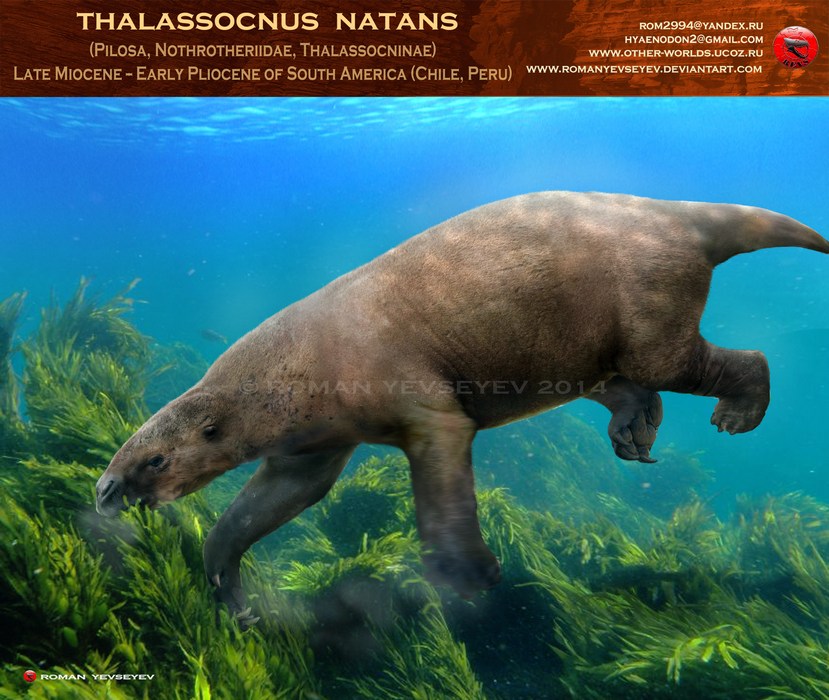

Thalassocnus spp.

A life restoration of Thalassocnus natans. © @ RomanYevseyev

Temporal range: Late Miocene-Late Pliocene (Tortonian-Zanclean: ~8-4Ma)

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Cephalochordata

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Clade: Eutheriodonta

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicynodontia

Infraorder: Eucynodontia

Parvorder: Probainognathia

Superfamily: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

Clade: Holotheria

Superlegion: Trechnotheria

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Eutheria

Infraclass: Placentalia

Subcohort: Exafroplacentalia

Superorder: Xenarthra

Order: Pilosa

Suborder: Folivora

Family: †Nothrotheriidae

Subfamily: †Thalassocninae

Genus: †Thalassocnus

Species: †T. antiquus

†T. natans

†T. littoralis

†T. carolomartini

†T. yaucensis

Head restoration of Thalassocnus yaucensis. © @ RomanYevseyev

Thalassocnus is a genus of extinct marine sloth that lived Peru and Chile[1] from ~8-4 million years ago.[2]

Species:

There were five species of Thalassocnus. The earliest was T. antiquus, which lived during the late Miocene, as did the later T. natans. T. littoralis lived during the early Pliocene while T. carolomartini lived during this time to the late Pliocene. The most derived species, T. yaucensis, lived during the late Pliocene.[3]

Paleobiology:

Thalassocnus was a marine animal that gradually became more adapted to living in the sea.

The rostrum was elongated and became even more so as time went on. The youngest species, T. yaucensis, had a longer rostrum than the oldest species, T. antiquus. Given how these sloths possessed long rostra and lived in coastal areas, they certainly did not feed on the same plants modern sloths consume.[3]

The dentition of the older species (namely T. antiquus, T. natans, T. littoralis) was found to have wear resulting from sand. These species would have stayed and fed close to the seashore (consuming plants that washed up on the beach or shallow-water plants) going into the water but not going "far out". Ergo, sand would have been consumed extensively, even if the animals went out to eat sea grass. These species apparently exhibit partial adaptations for grazing.[3][4]

The last two species did not have the extensive sand-induced wear on their dentition of their predecessors. Their dentition suggests that Thalassocnus became even more specialized and aquatic. They could go out further to consume aquatic plants further out into the sea. These two species had become specialized for grazing.[3][4] Their mandibles grew in length and had some sort of spoon shape at the end. Likewise, the skulls of these later species have openings for blood vessels, indicating the presence of powerful lips for grazing. Such an adaptation would be very useful because the powerful lips would permit Thalassocnus to feed without use of the forelimbs, which, with claws at the terminal ends of the fingers, would have been used for swimming and anchoring.[3]

Skulls of T. spp..

Lower jaws of T. spp..

Over time, Thalassocnus also evolved denser bones to create ballast in the water. This would have allowed the sloth to sink to the bottom of the water without expending a lot of energy.[2][5]

Evolution:

At the time of T. antiquus or so, the coast of Peru was apparently a desert with little food. Thus, the thalassocnines adapted to an aquatic lifestyle to consume marine plants.[6]

Extinction:

When the Panama Isthmus began to form (thus separating the Pacific Ocean from the Caribbean Sea), the waters around South America became significantly colder, killing off the aquatic plants Thalassocnus fed on. The sloth was either starved to extinction or too intolerant of the cold temperatures of the water.[6]

Skeleton of Thalassocnus.

References:

[1] "The Aquatic Sloth Thalassocnus (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the Late Miocene of North-Central Chile: Biogeographic and Ecological Implications" (Canto et al., 2008).

[2] How Aquatic Sloths Adapted To Their New Life In The Sea

[3] The Giant Swimming Sloths of South America

[4] "The evolution of feeding adaptations of the aquatic sloth Thalassocnus" (de Muizon et al., 2010).

[5] "Gradual adaptation of bone structure to aquatic lifestyle in extinct sloths from Peru" (Amson et al., 2014).

[6] www.livescience.com/44023-aquatic-sloths-had-dense-bones.html

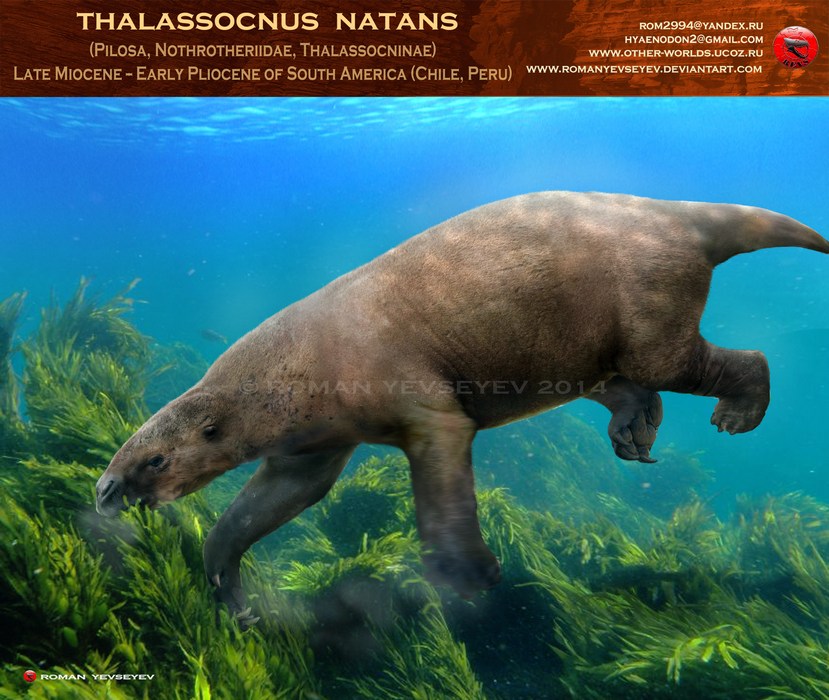

A life restoration of Thalassocnus natans. © @ RomanYevseyev

Temporal range: Late Miocene-Late Pliocene (Tortonian-Zanclean: ~8-4Ma)

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Cephalochordata

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Clade: Eutheriodonta

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicynodontia

Infraorder: Eucynodontia

Parvorder: Probainognathia

Superfamily: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

Clade: Holotheria

Superlegion: Trechnotheria

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Eutheria

Infraclass: Placentalia

Subcohort: Exafroplacentalia

Superorder: Xenarthra

Order: Pilosa

Suborder: Folivora

Family: †Nothrotheriidae

Subfamily: †Thalassocninae

Genus: †Thalassocnus

Species: †T. antiquus

†T. natans

†T. littoralis

†T. carolomartini

†T. yaucensis

Head restoration of Thalassocnus yaucensis. © @ RomanYevseyev

Thalassocnus is a genus of extinct marine sloth that lived Peru and Chile[1] from ~8-4 million years ago.[2]

Species:

There were five species of Thalassocnus. The earliest was T. antiquus, which lived during the late Miocene, as did the later T. natans. T. littoralis lived during the early Pliocene while T. carolomartini lived during this time to the late Pliocene. The most derived species, T. yaucensis, lived during the late Pliocene.[3]

Paleobiology:

Thalassocnus was a marine animal that gradually became more adapted to living in the sea.

The rostrum was elongated and became even more so as time went on. The youngest species, T. yaucensis, had a longer rostrum than the oldest species, T. antiquus. Given how these sloths possessed long rostra and lived in coastal areas, they certainly did not feed on the same plants modern sloths consume.[3]

The dentition of the older species (namely T. antiquus, T. natans, T. littoralis) was found to have wear resulting from sand. These species would have stayed and fed close to the seashore (consuming plants that washed up on the beach or shallow-water plants) going into the water but not going "far out". Ergo, sand would have been consumed extensively, even if the animals went out to eat sea grass. These species apparently exhibit partial adaptations for grazing.[3][4]

The last two species did not have the extensive sand-induced wear on their dentition of their predecessors. Their dentition suggests that Thalassocnus became even more specialized and aquatic. They could go out further to consume aquatic plants further out into the sea. These two species had become specialized for grazing.[3][4] Their mandibles grew in length and had some sort of spoon shape at the end. Likewise, the skulls of these later species have openings for blood vessels, indicating the presence of powerful lips for grazing. Such an adaptation would be very useful because the powerful lips would permit Thalassocnus to feed without use of the forelimbs, which, with claws at the terminal ends of the fingers, would have been used for swimming and anchoring.[3]

Skulls of T. spp..

Lower jaws of T. spp..

Over time, Thalassocnus also evolved denser bones to create ballast in the water. This would have allowed the sloth to sink to the bottom of the water without expending a lot of energy.[2][5]

Evolution:

At the time of T. antiquus or so, the coast of Peru was apparently a desert with little food. Thus, the thalassocnines adapted to an aquatic lifestyle to consume marine plants.[6]

Extinction:

When the Panama Isthmus began to form (thus separating the Pacific Ocean from the Caribbean Sea), the waters around South America became significantly colder, killing off the aquatic plants Thalassocnus fed on. The sloth was either starved to extinction or too intolerant of the cold temperatures of the water.[6]

Skeleton of Thalassocnus.

References:

[1] "The Aquatic Sloth Thalassocnus (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the Late Miocene of North-Central Chile: Biogeographic and Ecological Implications" (Canto et al., 2008).

[2] How Aquatic Sloths Adapted To Their New Life In The Sea

[3] The Giant Swimming Sloths of South America

[4] "The evolution of feeding adaptations of the aquatic sloth Thalassocnus" (de Muizon et al., 2010).

[5] "Gradual adaptation of bone structure to aquatic lifestyle in extinct sloths from Peru" (Amson et al., 2014).

[6] www.livescience.com/44023-aquatic-sloths-had-dense-bones.html