Post by Infinity Blade on Sept 1, 2016 4:41:07 GMT 5

Dinocrocuta spp.

Life restoration of Dinocrocuta. © @ Mauricio Antón.

Temporal range: Late Miocene (Tortonian; Bahean age[1]; ~8.7-7.75Ma[2])

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Clade: Eutheriodonta

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicynodontia

Infraorder: Eucynodontia

Parvorder: Probainognathia

Superfamily: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

Clade: Holotheria

Superlegion: Trechnotheria

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Eutheria

Infraclass: Placentalia

Subcohort: Exafroplacentalia

Magnorder: Boreoeutheria

Superorder: Laurasiatheria

(unranked): Ferae

(unranked): Carnivoramorpha

Order: Carnivora

Suborder: Feliformia

Family: †Percrocutidae? (or Hyaenidae)

Genus: †Dinocrocuta

Species: †D. gigantea

†D. macrodonta

Dinocrocuta is an extinct genus of hyena-like carnivoran that lived in the Hezheng Basin of central China[1] during the late Miocene ~8.7-7.75 million years ago[2].

Description:

Dinocrocuta was a large hyena-like predator. According to Mauricio Antón, Dinocrocuta likely doubled, if not tripled, the mass of the largest living hyenas (which is around 80 kilograms).[1]

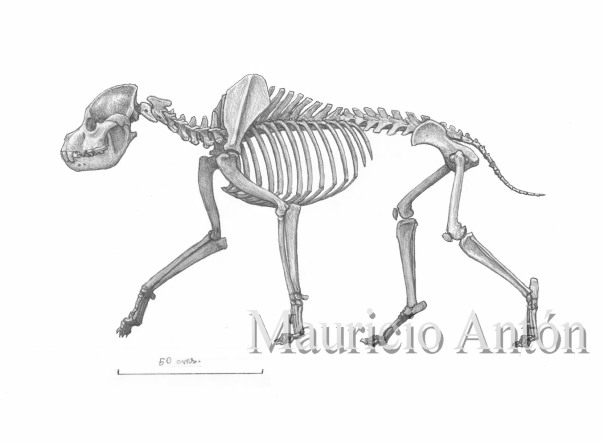

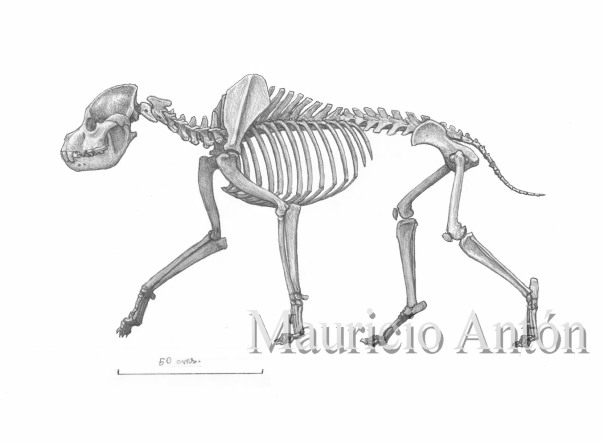

Skeletal restoration of Dinocrocuta. © @ Mauricio Antón.

It was found that the skulls of Dinocrocuta gigantea and Crocuta crocuta would be better at dissipating and distributing stress than Canis lupus. The highly domed frontal region of the former two would have facilitated stress dissipation and would be consistent with bone-cracking behavior. By contrast, the grey wolf, though it is capable of bone-crushing behavior*, is clearly not as adapted for this behavior as Dinocrocuta and the spotted hyena due to its very shallow forehead.[3] However, analysis of the mandibular biomechanics of these three carnivorans has yielded some noteworthy facts. During biting at P3, P4, and M1 (third premolar; fourth premolar; and first molar; respectively), mandibular stress was lowest in the spotted hyena and elevated in both the grey wolf and Dinocrocuta. Stress dissipation patterns of the pre-M1 corpus are similar in Dinocrocuta and the spotted hyena. But Dinocrocuta’s post-M1 corpus was slender and actually relatively weaker than that of the spotted hyena and grey wolf, meaning that the extinct carnivoran had a weaker mandible when performing a similar bone-cracking task as in the spotted hyena. It is worth noting that the individual studied in both of the aforementioned studies was a subadult individual. As such, the increase in biting performance in spotted hyenas throughout the course of their ontogeny may suggest that complete bone-cracking ability was relatively more delayed in Dinocrocuta than in the spotted hyena.[4]

*As noted by the author, a difference between bone-cracking and bone-crushing in ossiphageous mammalian carnivores is established by Werdelin (1989).

Predatory and scavenging behavior:

There is a specimen of a female Chilotherium wimani (an extinct rhinocerotid) whose skull was bitten by Dinocrocuta gigantea. The damage to the skull was interpreted as an injury inflicted by the percrocutid. This suggests that Dinocrocuta was an active predator, just like the extant spotted hyena.[5]

With its skeleton that was efficient for terrestrial locomotion, Dinocrocuta could have traveled far distances to search for carrion or prey. With its large body size and formidable armament, it could have evicted other carnivores from their kills.[1]

Skull of Dinocrocuta

Ecological implications:

According to Mauricio Antón, Dinocrocuta was the dominant large carnivore in Bahean-aged sediments. But by the Baeodean age, it was either very rare or extinct and was replaced by the much smaller true hyaenid Adcrocuta. The machairodont Amphimachairodus also became much more common after the extinction of Dinocrocuta. These facts suggest that Amphimachairodus’ frequency and dominance in the habitat were held back by competition from Dinocrocuta and that competition from Adcrocuta was not as suppressive on the cat.[1]

The actual cause of Dinocrocuta’s extinction is currently unknown.[1]

References:

[1] Sabertooth’s Bane: Introducing Dinocrocuta (article by Mauricio Antón)

[2] Fossilworks page on Dinocrocuta

[3] Tseng, Z.J. (2009). Cranial function in a late Miocene Dinocrocuta gigantea (Mammalia: Carnivora) revealed by comparative finite element analysis. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2009, 96, 51–67. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01095.x

[4] Tseng, Z.J.; Binder, W.J. (2010). Mandibular biomechanics of Crocuta crocuta, Canis lupus, and the late Miocene Dinocrocuta gigantea (Carnivora, Mammalia). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 158 (3): 683–696. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00555.x

[5] Deng, T.; Tseng, Z.J. (2010). Osteological evidence for predatory behavior of the giant percrocutid (Dinocrocuta gigantea) as an active hunter. Chinese Science Bulletin, June 2010, Volume 55, Issue 17, pp 1790–1794. doi:10.1007/s11434-010-3031-9

Life restoration of Dinocrocuta. © @ Mauricio Antón.

Temporal range: Late Miocene (Tortonian; Bahean age[1]; ~8.7-7.75Ma[2])

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Clade: Eutheriodonta

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicynodontia

Infraorder: Eucynodontia

Parvorder: Probainognathia

Superfamily: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

Clade: Holotheria

Superlegion: Trechnotheria

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Eutheria

Infraclass: Placentalia

Subcohort: Exafroplacentalia

Magnorder: Boreoeutheria

Superorder: Laurasiatheria

(unranked): Ferae

(unranked): Carnivoramorpha

Order: Carnivora

Suborder: Feliformia

Family: †Percrocutidae? (or Hyaenidae)

Genus: †Dinocrocuta

Species: †D. gigantea

†D. macrodonta

Dinocrocuta is an extinct genus of hyena-like carnivoran that lived in the Hezheng Basin of central China[1] during the late Miocene ~8.7-7.75 million years ago[2].

Description:

Dinocrocuta was a large hyena-like predator. According to Mauricio Antón, Dinocrocuta likely doubled, if not tripled, the mass of the largest living hyenas (which is around 80 kilograms).[1]

Skeletal restoration of Dinocrocuta. © @ Mauricio Antón.

It was found that the skulls of Dinocrocuta gigantea and Crocuta crocuta would be better at dissipating and distributing stress than Canis lupus. The highly domed frontal region of the former two would have facilitated stress dissipation and would be consistent with bone-cracking behavior. By contrast, the grey wolf, though it is capable of bone-crushing behavior*, is clearly not as adapted for this behavior as Dinocrocuta and the spotted hyena due to its very shallow forehead.[3] However, analysis of the mandibular biomechanics of these three carnivorans has yielded some noteworthy facts. During biting at P3, P4, and M1 (third premolar; fourth premolar; and first molar; respectively), mandibular stress was lowest in the spotted hyena and elevated in both the grey wolf and Dinocrocuta. Stress dissipation patterns of the pre-M1 corpus are similar in Dinocrocuta and the spotted hyena. But Dinocrocuta’s post-M1 corpus was slender and actually relatively weaker than that of the spotted hyena and grey wolf, meaning that the extinct carnivoran had a weaker mandible when performing a similar bone-cracking task as in the spotted hyena. It is worth noting that the individual studied in both of the aforementioned studies was a subadult individual. As such, the increase in biting performance in spotted hyenas throughout the course of their ontogeny may suggest that complete bone-cracking ability was relatively more delayed in Dinocrocuta than in the spotted hyena.[4]

*As noted by the author, a difference between bone-cracking and bone-crushing in ossiphageous mammalian carnivores is established by Werdelin (1989).

Predatory and scavenging behavior:

There is a specimen of a female Chilotherium wimani (an extinct rhinocerotid) whose skull was bitten by Dinocrocuta gigantea. The damage to the skull was interpreted as an injury inflicted by the percrocutid. This suggests that Dinocrocuta was an active predator, just like the extant spotted hyena.[5]

With its skeleton that was efficient for terrestrial locomotion, Dinocrocuta could have traveled far distances to search for carrion or prey. With its large body size and formidable armament, it could have evicted other carnivores from their kills.[1]

Skull of Dinocrocuta

Ecological implications:

According to Mauricio Antón, Dinocrocuta was the dominant large carnivore in Bahean-aged sediments. But by the Baeodean age, it was either very rare or extinct and was replaced by the much smaller true hyaenid Adcrocuta. The machairodont Amphimachairodus also became much more common after the extinction of Dinocrocuta. These facts suggest that Amphimachairodus’ frequency and dominance in the habitat were held back by competition from Dinocrocuta and that competition from Adcrocuta was not as suppressive on the cat.[1]

The actual cause of Dinocrocuta’s extinction is currently unknown.[1]

References:

[1] Sabertooth’s Bane: Introducing Dinocrocuta (article by Mauricio Antón)

[2] Fossilworks page on Dinocrocuta

[3] Tseng, Z.J. (2009). Cranial function in a late Miocene Dinocrocuta gigantea (Mammalia: Carnivora) revealed by comparative finite element analysis. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2009, 96, 51–67. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01095.x

[4] Tseng, Z.J.; Binder, W.J. (2010). Mandibular biomechanics of Crocuta crocuta, Canis lupus, and the late Miocene Dinocrocuta gigantea (Carnivora, Mammalia). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 158 (3): 683–696. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00555.x

[5] Deng, T.; Tseng, Z.J. (2010). Osteological evidence for predatory behavior of the giant percrocutid (Dinocrocuta gigantea) as an active hunter. Chinese Science Bulletin, June 2010, Volume 55, Issue 17, pp 1790–1794. doi:10.1007/s11434-010-3031-9