Post by creature386 on Jun 9, 2013 22:38:40 GMT 5

Pliosaurus kevani

Temporal range: Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic)[1]

Location: United Kingdom, Kimmeridge Clay Formation[1]

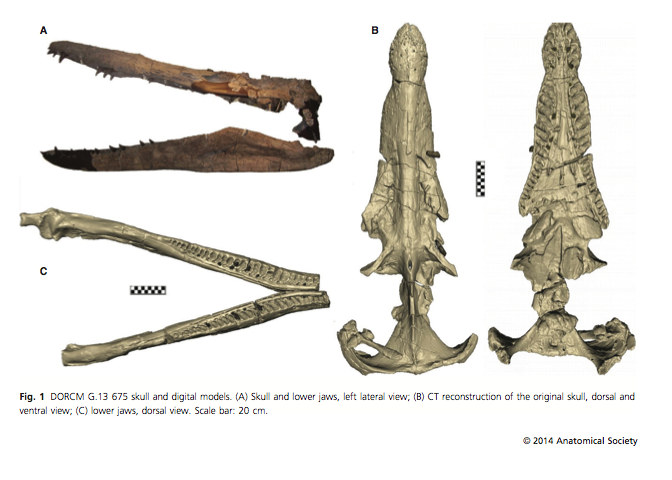

Figure 1. Locality and horizon of Pliosaurus kevani n. sp. DORCM G.13,675. Maps of the United Kingdom (A), Dorset area (B), and Osmington Bay (D) showing the locality of the specimen, indicated by a pliosaurid silhouette. The stratigraphic context of the find (C), the approximate level of the Wyke Siltstone bed is marked by a pliosaurid silhouette and the stratigraphic section at Black Head was given in full by ([63]:fig. 6). The mounted skull of DORCM G.13,675 in left lateral view (E). Scale bars equal 500 m (D) and 500 mm (E).[2]

© 2013 Benson et al.; Creative Commons Attribution License

Scientific classification:

Sauropterygia

Plesiosauria

Pliosauridae

Thalassophonea

Pliosaurus

P. kevani[3]

Specimen:

The holotype (DORCM G.13,675) is known from a very complete skull and it is the only specimen which can be reffered to the species with certainity.[4]

Figure 2. Cranium of Pliosaurus kevani n. sp. DORCM G.13,675 in dorsal view (A–B). In line drawing (B) dark grey tone represents broken bone surface, mid grey represents matrix, and light grey represents tooth or artificial restoration. Abbreviations: bat, basal tuber; en, external naris; exoc-opis, exoccipital-opisthotic; fr, frontal; jug, jugal; lac, ‘lacrimal’; mx, maxilla; pal, palatine; par parietal; pmx, premaxilla; po, postorbital; pofr, postfrontal; prfr, prefrontal; pt, pterygoid; rug, rugose eminence; soc (l), left portion of supraoccipital; soc (r), right portion of supraoccipital; sq, squamosal. Ss[5]

© 2013 Benson et al.; Creative Commons Attribution License

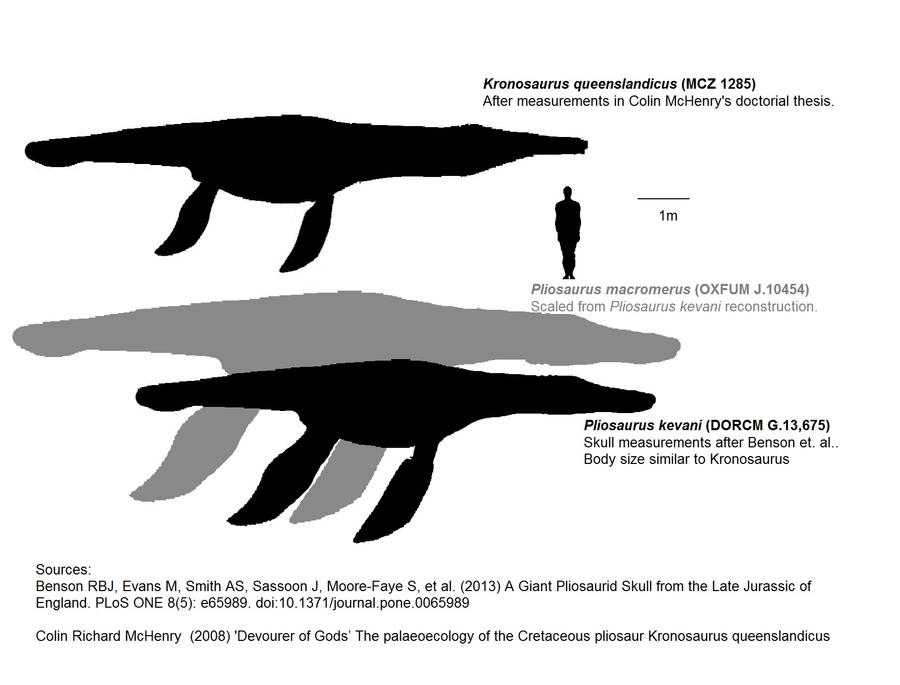

There is another specimen referred to it (CAMSM J.35990), which was formerly reffered to P. macromerus. The assignment is very unsure, but it was done on the basis of large body size and the presence of subtrihedral teeth (this is not evidenced in other pliosaurs). This specimen represents most of the postcranium, but only poorly preserved cranial material. It is therefore important, because the holotype is only known from a very complete skull. This of course swell means that there isn't a lot overlapping, so it was only tentatively referred, more coming material may change the assignment. Therefore no postcranial characters were listed. Another tentatively referred specimen is LEICT G418.1965.108, which too was referred on the basis of a subtrihedral tooth.[4]

Description:

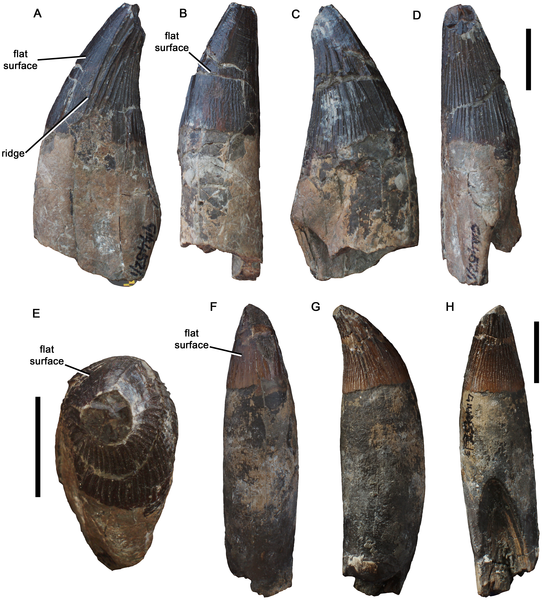

P. kevani was a large (total skull length of ~2 m[6]) pliosaur. Unique features include the (already mentioned) subtrihedral teeth, a high number of alveoli (of which six are closely juxtaposed in the premaxilla) and a slightly heterodont premaxillary dentition.[4] The dentition is relatively well preserved, most of the preserved teeth are still in the alveoli. All teeth are conical, curved and have a circular cross section.[7]

Figure 21. Teeth of Pliosaurus kevani n. sp. DORCM G.13,675. Large tooth in mesial or distal (A, C), labial (B), lingual (D), and apical (E) views. Small tooth in labial (F), mesial or distal (G), and lingual (H) views. Scale bars equal 20 mm.[8]

© 2013 Benson et al.; Creative Commons Attribution License

The mandibles are too well preserved, but most of the symphysis is missing. However, it's length still can be estimated at 400 mm.[9] Other complete portions of the cranium include the snout and dorsal surfaces of the skull.[0] The total length of P. kevani is believed to be similar to that of P. funkei, because both had roughly 2 m long skulls.[11]

Feeding and bite force:

P. kevani was a large and macrophagous predator. It is believed that P. kevani hunted proportionally larger prey than some other pliosaurs from the Late Jurassic, due to a proportionally shorter symphysis.[12] Such a trend can be observed in modern crocodiles.[13] Since pliosaurs were unable to use twist or shake strategies, that are observed in modern crocodiles[14], they very likely instead relied on powerful post-symphyseal bites.[15] The bite force of P. kevani at the caudal part of the tooth row has been estimated at 32 to 48 kN,[16] making its bite only a bit weaker than the highest estimates for Tyrannosaurus rex.[12]

Evidence from fossilized stomach contents of relatives as well as the fact that P. kevani was among the largest animals of the Kimmeridgian suggest that this animal was an unspecialized apex predator that was able to prey on most of the animals it was sympatric with.[15]

Phylogenetic position:

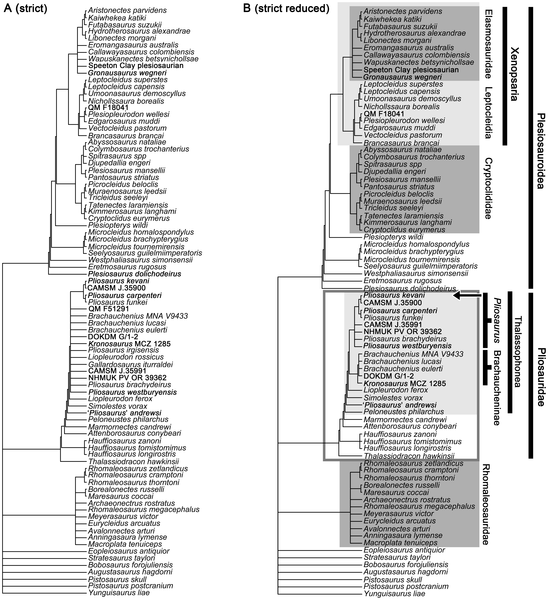

Figure 23. Phylogenetic position of Pliosaurus kevani n. sp. DORCM G.13,675. Strict (A) and strict reduced (B) consensus topologies of .130000 shortest length trees 1336 steps long resulting from analysis of our matrix of 85 taxa and 270 characters modified from [26]*. Shading is used to indicate major clades, Pliosauridae is enclosed by a grey rectangle, and Pliosaurus kevani n. sp. is indicated by an arrow.[17]

© 2013 Benson et al.; Creative Commons Attribution License

Literature:

Benson RBJ, Evans M, Smith AS, Sassoon J, Moore-Faye S, et al. (2013) A Giant Pliosaurid Skull from the Late Jurassic of England. PLoS ONE 8(5): e65989. p. 1-34 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065989

Walmsley CW, Smits PD, Quayle MR, McCurry MR, Richards HS, et al. (2013) Why the Long Face? The Mechanics of Mandibular Symphysis Proportions in Crocodiles. PLoS ONE 8(1): p. 1-34 e53873. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053873

Davide Foffa, Andrew R. Cuff, Judyth Sassoon, Emily J. Rayfield, Mark N. Mavrogordato and Michael J. Benton (2014) Functional anatomy and feeding biomechanics of a giant Upper Jurassic pliosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from Weymouth Bay, Dorset, UK. Journal of Anatomy p. 1-11 doi:10.1111/joa.12200

Footnotes:

[1] Benson et al. 2013 p. 1

[2] Benson et al. 2013 p. 2

[3] Benson et al. 2013 p. 4

[4] Benson et al. 2013 p. 5

[5] Benson et al. 2013 p. 6

[6] Benson et al. 2013 p. 28

[7] Benson et al. 2013 p. 27

[8] Benson et al. 2013 p. 23

[9] Benson et al. 2013 p. 26

[10] Benson et al. 2013 p. 11

[11] Benson et al. 2013 p. 31

[12] Foffa et al. p. 8

[13] Walmsley et al. 2013 p. 1

[14] Walmsley et al. 2013 p. 7

[15] Foffa et al. p. 9

[16] Foffa et al. p. 6

[17] Benson et al. 2013 p. 30

Annonation: By [26], this is meant:

Benson RBJ, Druckenmiller PS (2013) Faunal turnover of marine tetrapods during the Jurassic–Cretaceous transition. In: Biological Reviews doi:10.1111/brv.12038.

Temporal range: Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic)[1]

Location: United Kingdom, Kimmeridge Clay Formation[1]

Figure 1. Locality and horizon of Pliosaurus kevani n. sp. DORCM G.13,675. Maps of the United Kingdom (A), Dorset area (B), and Osmington Bay (D) showing the locality of the specimen, indicated by a pliosaurid silhouette. The stratigraphic context of the find (C), the approximate level of the Wyke Siltstone bed is marked by a pliosaurid silhouette and the stratigraphic section at Black Head was given in full by ([63]:fig. 6). The mounted skull of DORCM G.13,675 in left lateral view (E). Scale bars equal 500 m (D) and 500 mm (E).[2]

© 2013 Benson et al.; Creative Commons Attribution License

Scientific classification:

Sauropterygia

Plesiosauria

Pliosauridae

Thalassophonea

Pliosaurus

P. kevani[3]

Specimen:

The holotype (DORCM G.13,675) is known from a very complete skull and it is the only specimen which can be reffered to the species with certainity.[4]

Figure 2. Cranium of Pliosaurus kevani n. sp. DORCM G.13,675 in dorsal view (A–B). In line drawing (B) dark grey tone represents broken bone surface, mid grey represents matrix, and light grey represents tooth or artificial restoration. Abbreviations: bat, basal tuber; en, external naris; exoc-opis, exoccipital-opisthotic; fr, frontal; jug, jugal; lac, ‘lacrimal’; mx, maxilla; pal, palatine; par parietal; pmx, premaxilla; po, postorbital; pofr, postfrontal; prfr, prefrontal; pt, pterygoid; rug, rugose eminence; soc (l), left portion of supraoccipital; soc (r), right portion of supraoccipital; sq, squamosal. Ss[5]

© 2013 Benson et al.; Creative Commons Attribution License

There is another specimen referred to it (CAMSM J.35990), which was formerly reffered to P. macromerus. The assignment is very unsure, but it was done on the basis of large body size and the presence of subtrihedral teeth (this is not evidenced in other pliosaurs). This specimen represents most of the postcranium, but only poorly preserved cranial material. It is therefore important, because the holotype is only known from a very complete skull. This of course swell means that there isn't a lot overlapping, so it was only tentatively referred, more coming material may change the assignment. Therefore no postcranial characters were listed. Another tentatively referred specimen is LEICT G418.1965.108, which too was referred on the basis of a subtrihedral tooth.[4]

Description:

P. kevani was a large (total skull length of ~2 m[6]) pliosaur. Unique features include the (already mentioned) subtrihedral teeth, a high number of alveoli (of which six are closely juxtaposed in the premaxilla) and a slightly heterodont premaxillary dentition.[4] The dentition is relatively well preserved, most of the preserved teeth are still in the alveoli. All teeth are conical, curved and have a circular cross section.[7]

Figure 21. Teeth of Pliosaurus kevani n. sp. DORCM G.13,675. Large tooth in mesial or distal (A, C), labial (B), lingual (D), and apical (E) views. Small tooth in labial (F), mesial or distal (G), and lingual (H) views. Scale bars equal 20 mm.[8]

© 2013 Benson et al.; Creative Commons Attribution License

The mandibles are too well preserved, but most of the symphysis is missing. However, it's length still can be estimated at 400 mm.[9] Other complete portions of the cranium include the snout and dorsal surfaces of the skull.[0] The total length of P. kevani is believed to be similar to that of P. funkei, because both had roughly 2 m long skulls.[11]

Feeding and bite force:

P. kevani was a large and macrophagous predator. It is believed that P. kevani hunted proportionally larger prey than some other pliosaurs from the Late Jurassic, due to a proportionally shorter symphysis.[12] Such a trend can be observed in modern crocodiles.[13] Since pliosaurs were unable to use twist or shake strategies, that are observed in modern crocodiles[14], they very likely instead relied on powerful post-symphyseal bites.[15] The bite force of P. kevani at the caudal part of the tooth row has been estimated at 32 to 48 kN,[16] making its bite only a bit weaker than the highest estimates for Tyrannosaurus rex.[12]

Evidence from fossilized stomach contents of relatives as well as the fact that P. kevani was among the largest animals of the Kimmeridgian suggest that this animal was an unspecialized apex predator that was able to prey on most of the animals it was sympatric with.[15]

Phylogenetic position:

Figure 23. Phylogenetic position of Pliosaurus kevani n. sp. DORCM G.13,675. Strict (A) and strict reduced (B) consensus topologies of .130000 shortest length trees 1336 steps long resulting from analysis of our matrix of 85 taxa and 270 characters modified from [26]*. Shading is used to indicate major clades, Pliosauridae is enclosed by a grey rectangle, and Pliosaurus kevani n. sp. is indicated by an arrow.[17]

© 2013 Benson et al.; Creative Commons Attribution License

Literature:

Benson RBJ, Evans M, Smith AS, Sassoon J, Moore-Faye S, et al. (2013) A Giant Pliosaurid Skull from the Late Jurassic of England. PLoS ONE 8(5): e65989. p. 1-34 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065989

Walmsley CW, Smits PD, Quayle MR, McCurry MR, Richards HS, et al. (2013) Why the Long Face? The Mechanics of Mandibular Symphysis Proportions in Crocodiles. PLoS ONE 8(1): p. 1-34 e53873. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053873

Davide Foffa, Andrew R. Cuff, Judyth Sassoon, Emily J. Rayfield, Mark N. Mavrogordato and Michael J. Benton (2014) Functional anatomy and feeding biomechanics of a giant Upper Jurassic pliosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from Weymouth Bay, Dorset, UK. Journal of Anatomy p. 1-11 doi:10.1111/joa.12200

Footnotes:

[1] Benson et al. 2013 p. 1

[2] Benson et al. 2013 p. 2

[3] Benson et al. 2013 p. 4

[4] Benson et al. 2013 p. 5

[5] Benson et al. 2013 p. 6

[6] Benson et al. 2013 p. 28

[7] Benson et al. 2013 p. 27

[8] Benson et al. 2013 p. 23

[9] Benson et al. 2013 p. 26

[10] Benson et al. 2013 p. 11

[11] Benson et al. 2013 p. 31

[12] Foffa et al. p. 8

[13] Walmsley et al. 2013 p. 1

[14] Walmsley et al. 2013 p. 7

[15] Foffa et al. p. 9

[16] Foffa et al. p. 6

[17] Benson et al. 2013 p. 30

Annonation: By [26], this is meant:

Benson RBJ, Druckenmiller PS (2013) Faunal turnover of marine tetrapods during the Jurassic–Cretaceous transition. In: Biological Reviews doi:10.1111/brv.12038.