Post by Vodmeister on Feb 28, 2014 23:50:26 GMT 5

Basilosaurus spp.

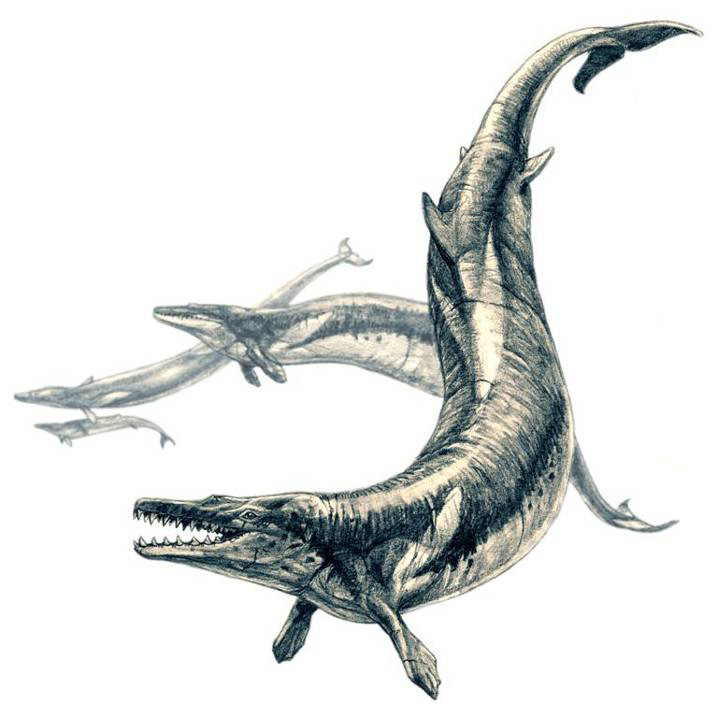

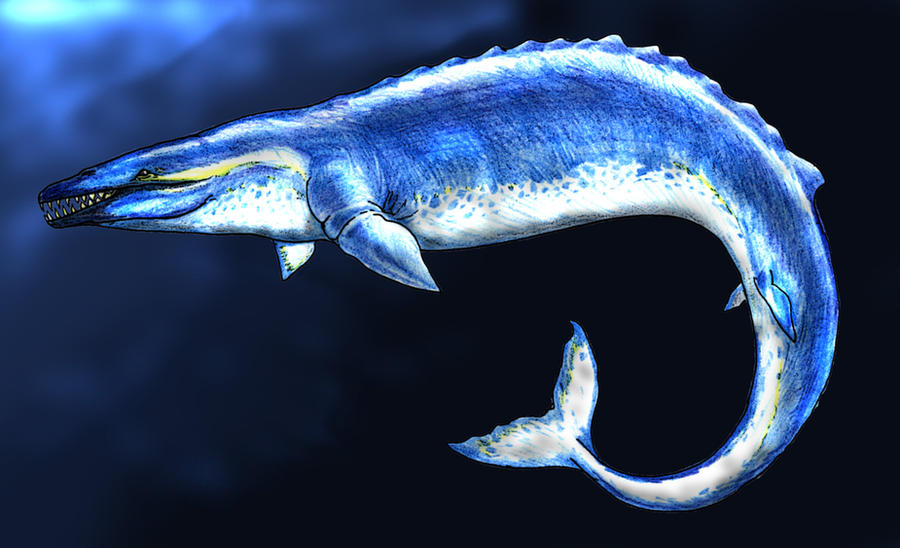

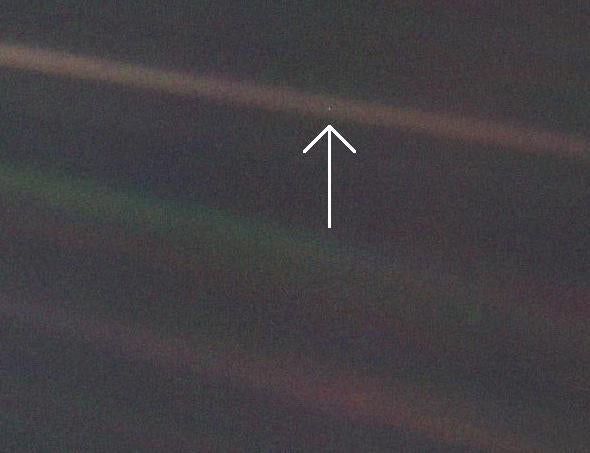

Life restoration of Basilosaurus swimming. © @ Sergio Pérez.

Temporal range: Paleogene; Eocene; Bartonian to early Priabonian (~41.2 to >33.9 Ma)[1][2]

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicynodontia

Infraorder: Eucynodontia

Parvorder: Probainognathia

Superfamily: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

Clade: Holotheria

Superlegion: Trechnotheria

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Eutheria

Infraclass: Placentalia

Subcohort: Exafroplacentalia

Magnorder: Boreoeutheria

Superorder: Laurasiatheria

Clade: Ungulata

Clade: Cetartiodactyla

Family: †Basilosauridae

Subfamily: †Basilosaurinae

Genus: †Basilosaurus

Species: †B. cetoides

†B. isis

Basilosaurus is an extinct genus of cetacean that lived in the United States, Egypt, Germany, Jordan, the western Sahara[3][4], and possibly Antarctica[5] from the Bartonian to the early Priabonian[1], existing between 41.2 to 33.9 million years ago.

Taxonomy:

Despite the rather unfitting name “Basilosaurus” (“king lizard”), this genus name has priority over Zeuglodon and several other synonyms.[1] Currently, the two known valid species are B. cetoides (the type species) and B. isis. There used to be a third species classified in this genus (Basilosaurus drazindai), but this has since been reassigned to the genus Eocetus.[6][7]

Description:

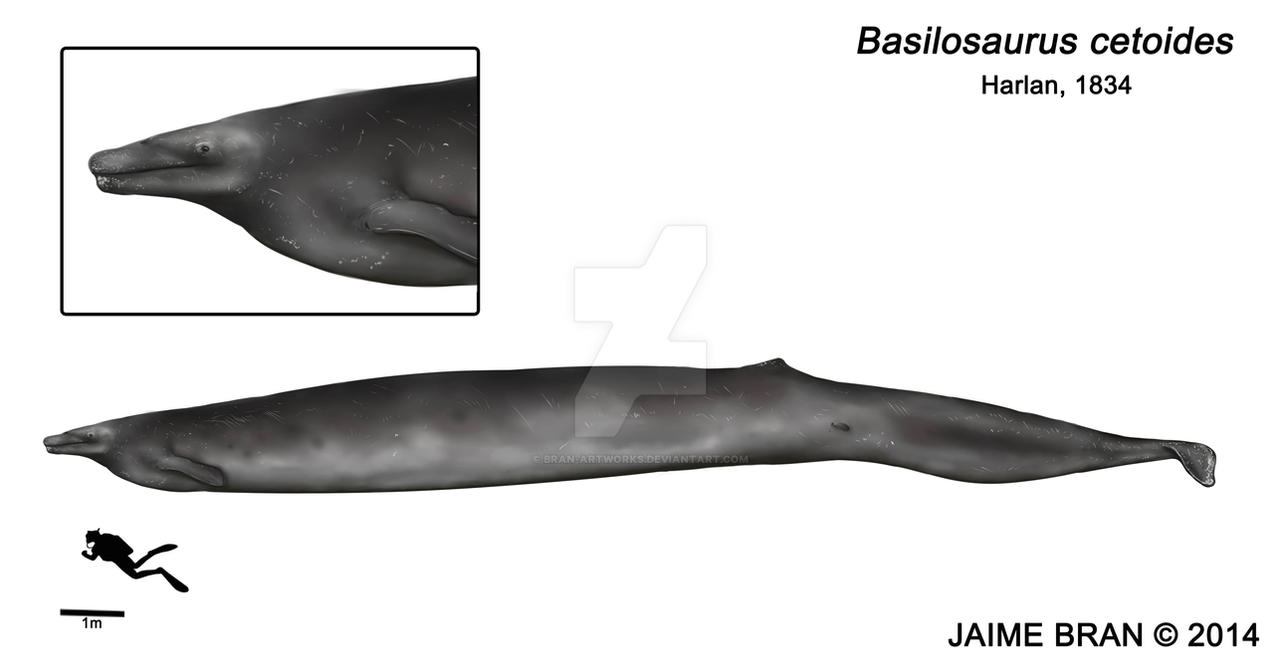

B. cetoides was slightly larger than B. isis[1], at 17-20 meters versus 15-18 meters in total length, respectively.[8] Due to its elongated body it might not have exceeded, or even achieved, 10 tonnes in total body mass.[9] The skull was relatively small for its total body length, with the skull of B. isis at 113 cm long.[10]

The dental formula of B. isis is 3.1.4.2/3.1.4.3.[11] Unlike modern toothed whales, Basilosaurus teeth were clearly heterodont. The upper and lower molars, as well as upper & lower premolars 2-4 were double-rooted and high-crowned; these teeth sported a central cusp and anteroposteriorly oriented accessory denticles. The molars were smaller, more closely spaced, and lower-crowned. Incisors and canines were monocuspid.[11]

Skeleton of Basilosaurus compared to Dorudon. From [8].

Skull of B. isis. Note the clearly heterodont dentition in comparison to modern odontocetes. Image source.

Basilosaurus had extremely reduced hindlimbs. These were of no use for locomotion on land or underwater, but the retention of joints and insertions for muscles, among others, might suggest some use for assisting reproduction.[12] It may be, however, that the hindlimbs had no clear function. Once hindlimbs became unnecessary in cetaceans, there may have been a long period of time where they existed in a highly reduced form before disappearing completely.[13]

Biology:

The serpentine body of Basilosaurus may suggest anguilliform locomotion. The very dense ribs, oxygen isotope chemistry of the teeth, and the fact that Basilosaurus remains have only been found in marine deposits, are all evidence of a fully marine animal.[13]

The lower jaw contained a very large mandibular foramen with thin walls, suggesting the presence of a fat pad that detected sound waves underwater. Basilosaurus had bony external ear canals unlike modern cetaceans, but all other hearing adaptations are indicative of a fully marine animal. Therefore, the remaining adaptations for hearing airborne sound were likely vestigial.[13]

Basilosaurus was an apex predator in its ecosystem, just like other cetaceans such as Livyatan melvillei and Orcinus orca.[8] Stomach contents of B. cetoides included the remains of fishes and sharks up to 50 cm in length.[14] By contrast, evidence shows that B. isis preyed also preyed upon marine mammals, especially Dorudon calves. Skulls of juvenile Dorudon have been found that match the teeth of B. isis. The prey was sometimes captured with one bite and readjusted for a more powerful killing bite using the premolars.[11] A study on the bite force of B. isis estimated its bite force at the third premolar to be at least ~16,400 N, with a second incisor bite force of at least 10,536 N, showing that Basilosaurus had jaws strong enough to break bones (i.e. the skulls of juvenile Dorudon).[10] It’s been suggested that the long, narrow rostrum of Basilosaurus meant it was unlikely to have rammed its prey like modern orcas do[11], although odontocetes with longirostrine jaws (e.g. bottlenose dolphins) also ram other animals with their rostrum.[15]

It has been suggested that the different Basilosaurus species had different diets, similar to how modern orca populations show considerable variation and specialization in diet.[11] It is indeed true that B. cetoides fed on fishes and sharks, and that B. isis fed on other cetaceans. B. isis, however, did not feed exclusively on marine mammals, as the stomach contents of an adult male B. isis specimen include the remains of both juvenile Dorudon and the fish Pycnodus mokattamensis.[8]

Extinction:

Basilosaurus has no living descendants, and did not give rise to any later whales.[16] It is possible that the progressive cooling of the Earth’s climate[16] changed ocean circulation, leading to the extinction of Basilosaurus.[17]

References:

[1] Thewissen, J. G. (Ed.). (2013). The emergence of whales: evolutionary patterns in the origin of Cetacea (Vol. 1). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 32-33.

[2] stratigraphy.org/ICSchart/ChronostratChart2021-05.pdf

[3] paleobiodb.org/classic/basicTaxonInfo?taxon_no=63132

[4] paleobiodb.org/classic/basicTaxonInfo?taxon_no=53287

[5] REGUERO, M. A. (2019). [url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335383837_Antarctic_Paleontological_Heritage_Late_Cretaceous-Paleogene_vertebrates_from_Seymour_Marambio_Island_Antarctic_PeninsulaAntarctic Paleontological Heritage: Late Cretaceous–Paleogene vertebrates from Seymour (Marambio) Island, Antarctic Peninsula[/url]. Advances in Polar Science, 328-355.

[6] Gingerich, P. D., & Zouhri, S. (2015). New fauna of archaeocete whales (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Bartonian middle Eocene of southern Morocco. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 111, 273-286.

[7] Jan van Vliet, H., Lambert, O., Bosselaers, M., S Schulp, A., & WM Jagt, J. (2019). A Palaeogene cetacean from Maastricht, southern Limburg (The Netherlands). Cainozoic research, 19(1), 95-113.

[8] Voss, M., Antar, M. S. M., Zalmout, I. S., & Gingerich, P. D. (2019). Stomach contents of the archaeocete Basilosaurus isis: Apex predator in oceans of the late Eocene. PloS one, 14(1), e0209021.

[9] McHenry, C. R. (2009). Devourer of gods. The palaeoecology of the Cretaceous pliosaur Kronosaurus queenslandicus.

[10] Snively, E., Fahlke, J. M., & Welsh, R. C. (2015). Bone-breaking bite force of Basilosaurus isis (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the late Eocene of Egypt estimated by finite element analysis. PloS One, 10(2), e0118380.

[11] Fahlke, J. M. (2012). Bite marks revisited—evidence for middle-to-late Eocene Basilosaurus isis predation on Dorudon atrox (both Cetacea, Basilosauridae). Palaeontologia Electronica, 15(3), 32A.

[12] Gingerich, P. D., Smith, B. H., & Simons, E. L. (1990). Hind limbs of Eocene Basilosaurus: evidence of feet in whales. Science, 249(4965), 154-157.

[13] www.nyit.edu/medicine/basilosaurus_spp

[14] Swift, C., & Barnes, L. (1996). Stomach Contents of Basilosaurus Cetoides: Implications for the Evolution of Cetacean Feeding Behavior, and Evidence for Vertebrate Fauna of Epicontinental Eocene Seas. The Paleontological Society Special Publications, 8, 380-380. doi:10.1017/S2475262200003828

[15] Cotter, M. P., Maldini, D., & Jefferson, T. A. (2012). “Porpicide” in California: Killing of harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) by coastal bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Marine Mammal Science, 28(1), E1-E15.

[16] Ivany, L. C., Patterson, W. P., & Lohmann, K. C. (2000). Cooler winters as a possible cause of mass extinctions at the Eocene/Oligocene boundary. Nature, 407(6806), 887-890.

[17] web.archive.org/web/20140313151405/http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/face/Article.jsp?id=h-1386

Life restoration of Basilosaurus swimming. © @ Sergio Pérez.

Temporal range: Paleogene; Eocene; Bartonian to early Priabonian (~41.2 to >33.9 Ma)[1][2]

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicynodontia

Infraorder: Eucynodontia

Parvorder: Probainognathia

Superfamily: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

Clade: Holotheria

Superlegion: Trechnotheria

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Eutheria

Infraclass: Placentalia

Subcohort: Exafroplacentalia

Magnorder: Boreoeutheria

Superorder: Laurasiatheria

Clade: Ungulata

Clade: Cetartiodactyla

Family: †Basilosauridae

Subfamily: †Basilosaurinae

Genus: †Basilosaurus

Species: †B. cetoides

†B. isis

Basilosaurus is an extinct genus of cetacean that lived in the United States, Egypt, Germany, Jordan, the western Sahara[3][4], and possibly Antarctica[5] from the Bartonian to the early Priabonian[1], existing between 41.2 to 33.9 million years ago.

Taxonomy:

Despite the rather unfitting name “Basilosaurus” (“king lizard”), this genus name has priority over Zeuglodon and several other synonyms.[1] Currently, the two known valid species are B. cetoides (the type species) and B. isis. There used to be a third species classified in this genus (Basilosaurus drazindai), but this has since been reassigned to the genus Eocetus.[6][7]

Description:

B. cetoides was slightly larger than B. isis[1], at 17-20 meters versus 15-18 meters in total length, respectively.[8] Due to its elongated body it might not have exceeded, or even achieved, 10 tonnes in total body mass.[9] The skull was relatively small for its total body length, with the skull of B. isis at 113 cm long.[10]

The dental formula of B. isis is 3.1.4.2/3.1.4.3.[11] Unlike modern toothed whales, Basilosaurus teeth were clearly heterodont. The upper and lower molars, as well as upper & lower premolars 2-4 were double-rooted and high-crowned; these teeth sported a central cusp and anteroposteriorly oriented accessory denticles. The molars were smaller, more closely spaced, and lower-crowned. Incisors and canines were monocuspid.[11]

Skeleton of Basilosaurus compared to Dorudon. From [8].

Skull of B. isis. Note the clearly heterodont dentition in comparison to modern odontocetes. Image source.

Basilosaurus had extremely reduced hindlimbs. These were of no use for locomotion on land or underwater, but the retention of joints and insertions for muscles, among others, might suggest some use for assisting reproduction.[12] It may be, however, that the hindlimbs had no clear function. Once hindlimbs became unnecessary in cetaceans, there may have been a long period of time where they existed in a highly reduced form before disappearing completely.[13]

Biology:

The serpentine body of Basilosaurus may suggest anguilliform locomotion. The very dense ribs, oxygen isotope chemistry of the teeth, and the fact that Basilosaurus remains have only been found in marine deposits, are all evidence of a fully marine animal.[13]

The lower jaw contained a very large mandibular foramen with thin walls, suggesting the presence of a fat pad that detected sound waves underwater. Basilosaurus had bony external ear canals unlike modern cetaceans, but all other hearing adaptations are indicative of a fully marine animal. Therefore, the remaining adaptations for hearing airborne sound were likely vestigial.[13]

Basilosaurus was an apex predator in its ecosystem, just like other cetaceans such as Livyatan melvillei and Orcinus orca.[8] Stomach contents of B. cetoides included the remains of fishes and sharks up to 50 cm in length.[14] By contrast, evidence shows that B. isis preyed also preyed upon marine mammals, especially Dorudon calves. Skulls of juvenile Dorudon have been found that match the teeth of B. isis. The prey was sometimes captured with one bite and readjusted for a more powerful killing bite using the premolars.[11] A study on the bite force of B. isis estimated its bite force at the third premolar to be at least ~16,400 N, with a second incisor bite force of at least 10,536 N, showing that Basilosaurus had jaws strong enough to break bones (i.e. the skulls of juvenile Dorudon).[10] It’s been suggested that the long, narrow rostrum of Basilosaurus meant it was unlikely to have rammed its prey like modern orcas do[11], although odontocetes with longirostrine jaws (e.g. bottlenose dolphins) also ram other animals with their rostrum.[15]

It has been suggested that the different Basilosaurus species had different diets, similar to how modern orca populations show considerable variation and specialization in diet.[11] It is indeed true that B. cetoides fed on fishes and sharks, and that B. isis fed on other cetaceans. B. isis, however, did not feed exclusively on marine mammals, as the stomach contents of an adult male B. isis specimen include the remains of both juvenile Dorudon and the fish Pycnodus mokattamensis.[8]

Extinction:

Basilosaurus has no living descendants, and did not give rise to any later whales.[16] It is possible that the progressive cooling of the Earth’s climate[16] changed ocean circulation, leading to the extinction of Basilosaurus.[17]

References:

[1] Thewissen, J. G. (Ed.). (2013). The emergence of whales: evolutionary patterns in the origin of Cetacea (Vol. 1). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 32-33.

[2] stratigraphy.org/ICSchart/ChronostratChart2021-05.pdf

[3] paleobiodb.org/classic/basicTaxonInfo?taxon_no=63132

[4] paleobiodb.org/classic/basicTaxonInfo?taxon_no=53287

[5] REGUERO, M. A. (2019). [url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335383837_Antarctic_Paleontological_Heritage_Late_Cretaceous-Paleogene_vertebrates_from_Seymour_Marambio_Island_Antarctic_PeninsulaAntarctic Paleontological Heritage: Late Cretaceous–Paleogene vertebrates from Seymour (Marambio) Island, Antarctic Peninsula[/url]. Advances in Polar Science, 328-355.

[6] Gingerich, P. D., & Zouhri, S. (2015). New fauna of archaeocete whales (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Bartonian middle Eocene of southern Morocco. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 111, 273-286.

[7] Jan van Vliet, H., Lambert, O., Bosselaers, M., S Schulp, A., & WM Jagt, J. (2019). A Palaeogene cetacean from Maastricht, southern Limburg (The Netherlands). Cainozoic research, 19(1), 95-113.

[8] Voss, M., Antar, M. S. M., Zalmout, I. S., & Gingerich, P. D. (2019). Stomach contents of the archaeocete Basilosaurus isis: Apex predator in oceans of the late Eocene. PloS one, 14(1), e0209021.

[9] McHenry, C. R. (2009). Devourer of gods. The palaeoecology of the Cretaceous pliosaur Kronosaurus queenslandicus.

[10] Snively, E., Fahlke, J. M., & Welsh, R. C. (2015). Bone-breaking bite force of Basilosaurus isis (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the late Eocene of Egypt estimated by finite element analysis. PloS One, 10(2), e0118380.

[11] Fahlke, J. M. (2012). Bite marks revisited—evidence for middle-to-late Eocene Basilosaurus isis predation on Dorudon atrox (both Cetacea, Basilosauridae). Palaeontologia Electronica, 15(3), 32A.

[12] Gingerich, P. D., Smith, B. H., & Simons, E. L. (1990). Hind limbs of Eocene Basilosaurus: evidence of feet in whales. Science, 249(4965), 154-157.

[13] www.nyit.edu/medicine/basilosaurus_spp

[14] Swift, C., & Barnes, L. (1996). Stomach Contents of Basilosaurus Cetoides: Implications for the Evolution of Cetacean Feeding Behavior, and Evidence for Vertebrate Fauna of Epicontinental Eocene Seas. The Paleontological Society Special Publications, 8, 380-380. doi:10.1017/S2475262200003828

[15] Cotter, M. P., Maldini, D., & Jefferson, T. A. (2012). “Porpicide” in California: Killing of harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) by coastal bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Marine Mammal Science, 28(1), E1-E15.

[16] Ivany, L. C., Patterson, W. P., & Lohmann, K. C. (2000). Cooler winters as a possible cause of mass extinctions at the Eocene/Oligocene boundary. Nature, 407(6806), 887-890.

[17] web.archive.org/web/20140313151405/http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/face/Article.jsp?id=h-1386