|

|

Post by Life on Aug 4, 2010 1:11:50 GMT 5

Livyatan melvillei Scientific classification: Scientific classification:| Kingdom: | Animalia | | Phylum: | Chordata | | Class: | Mammalia | | Order: | Cetacea | | Superfamily: | Physeteroidea | | Genus: | Livyatan | | Species: | L. melvillei |

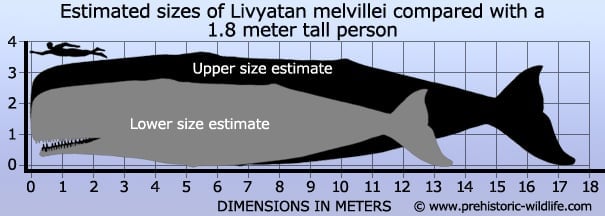

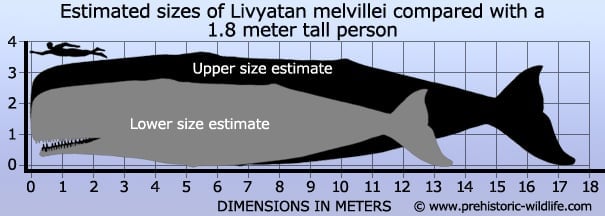

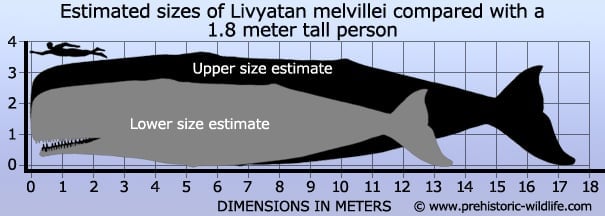

This species was originally named Leviathan melvillei in the summer of 2010. As it turned out, the name Leviathan had already been used for a mastodon, an extinct type of elephant. Rules established by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature prohibit this, otherwise confusing situations could develop because different species share the same name. Thus the authors renamed their new species Livyatan, which is the original Hebrew spelling (Leviathan is the English spelling). Age:12-13 million years old, Miocene Epoch. Range:The only known specimen of Livyatan was reported from Peru, indicating that it inhabited the southeastern Pacific Ocean. Size:Based on the size of the 3 meter (approximately ten feet) long skull and on comparisons with other sperm whales, Livyatan had a body length of 13.5 - 17.5 meters (44 - 57 feet).  Anatomy: Anatomy:The skull and lower jaws of Livyatan are gigantic and massive. Unlike the modern sperm whale (Physeter), Livyatan possessed massive, deeply rooted upper teeth and a short, wide snout. The modern sperm whale lacks upper teeth, and has a very long, less robust snout. Similar to the modern sperm whale, Livyatan exhibited a concave surface on the top of the skull called the 'supracranial basin,' which presumably housed a large fluid-filled sac called the 'spermaceti organ'. The teeth of Livyatan are large (~14 inches long, 4-5 inches in width – nearly the size of a 2-liter bottle of soda, and more than double the size of the largest known Tyrannosaurus rex teeth), have sharp tips, and bear deep gouges from wearing against other teeth. Locomotion:Although most of the skeleton of Livyatan is unknown, primitive sperm whales of a similar evolutionary grade, like Zygophyseter,have skeletons that are much like those of modern sperm whales. This suggests that Livyatan was fully marine and an efficient swimmer. Sensory abilities:The skull of Livyatan has a large depression on the top of the skull (the 'supracranial basin'), which in modern sperm whales houses the 'spermaceti organ' and the melon, two soft tissue organs which function in echolocation. This suggests that Livyatan could echolocate in a manner similar to modern sperm and pygmy sperm whales (Physeter and Kogia). Diet: The snout and the teeth of Livyatan indicate that it fed in a manner that is very different than the modern sperm whale, Physeter. The modern sperm whale feeds on large squid using oral suction, and its teeth are not used for chewing prey. The deep diving capabilities of Livyatan are as yet unknown, but the modern sperm whale Physeter is the deepest diving marine mammal, allowing it to pursue large squid at great depths. The only hard parts to squids are the beaks, which are composed of chitin (a hard protein structure; chitin also forms insect exoskeletons). The robust snout and massive lower and upper teeth of Livyatan are evidence that its prey were larger and tougher than squid. Additionally, the relative size of the attachment area for the temporalis - the primary jaw closing muscle - is much larger (relative to skull size) than in Physeter, and is similar to that of the killer whale ( Orcinus orca). It has been hypothesized that due to many of these features, Livyatan occupied a giant-killer whale like niche, and preyed upon baleen whales and other large marine mammals. The mouth of Livyatan is approximately six feet long and four feet wide – three times the size of the mouth of the killer whale (Orcinus), and large enough to fit an adult human (or the entire head of a Tyrannosaurus rex). References:Lambert, O., Bianucci, G., Post, K., Muizon, C. de., Salas-Gismondi, R., Urbina, M., and J. Reumer. 2010. The giant bite of a new raptorial sperm whale from the Miocene epoch of Peru. Nature 466:105-108. ---- Information obtained from:www.nyit.edu/medicine//research/cetacean_family_tree_Livyatan_melvilleiwww.gbif.org/species/3240234www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/species/l/livyatan.htmlen.wikipedia.org/wiki/Livyatan_melvillei

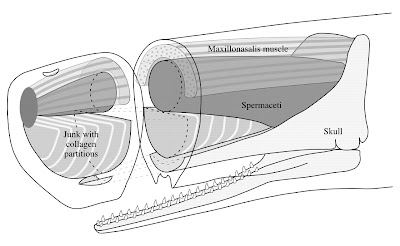

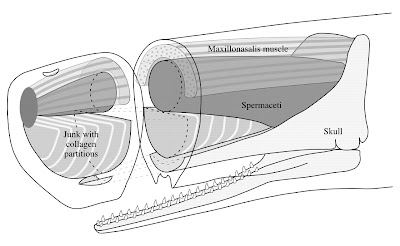

Call me Leviathan melvilleiSperm whale fossil has the biggest whale bite ever seen.Janet Fang  A Peruvian desert has turned out to be the final resting place of an ancient sperm whale with teeth much bigger than those of the largest of today's sperm whales. The fossil, dated at 12–13 million years old, belongs to a new, but extinct, genus and species described in Nature today1. Named Leviathan melvillei, it probably hunted baleen whales. A team of researchers recovered 75% of the animal's skull, complete with large fragments of both jaws and several teeth. On the basis of its skull length of 3 metres, they estimate that Leviathan was probably 13.5–17.5 metres long, within the range of extant adult male sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus). Its largest teeth, however, are more than 36 centimetres long — nearly 10 centimetres longer than the largest recorded Physeter tooth. Modern sperm whales lack functional teeth in their upper jaw and feed by suction, diving deep to hunt squid. Conversely, Leviathan had massive teeth in both its upper and lower jaws, and a skull that supported large jaw muscles. It may have hunted like raptorial killer whales, which use their teeth to tear off flesh (See Nature's video). Co-author Klaas Post of the Natural History Museum Rotterdam in the Netherlands stumbled across the fossil in November 2008 during the final day of a field trip to Cerro Colorado in the Pisco-Ica Desert on the southern coast of Peru — an area that is now above sea level owing to Andean tectonic activities. The fossils were prepared in Lima, where they will remain. Moby monikerThe name given to the creature combines the Hebrew word 'Livyatan', which refers to large mythological sea monsters, with the name of American novelist Herman Melville, who penned Moby-Dick — "one of my favourite sea books", says lead author Olivier Lambert of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris.  The authors think that Leviathan, like the extinct giant shark, preyed on medium-sized baleen whales, which were between 7 and 10 metres long, smaller than today's humpback whales and widely diverse at the time. The authors speculate that Leviathan became extinct as a result of changing environmental conditions. "Top predators are very sensitive to the changes in their prey," Lambert says. Changes in number, diversity or size of baleen whales, as well as the climate cooling that occurred at around Leviathan 's time, would have had dire impacts. The creature's surviving cousins — Physeter, pygmy and dwarf sperm whales — are specialized deep-diving squid hunters that occupy a different ecological niche from Leviathan. According to vertebrate palaeontologist Lawrence Barnes at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, this discovery demonstrates that sperm whale-like cetaceans were much more diverse in the past and that the modern sperm whale and pygmy sperm whales are the "only surviving vestiges of a larger evolutionary radiation of related whales in the past". Battering ramsAll sperm whales have characteristically large foreheads to hold their 'spermaceti organ', a series of oil and wax reservoirs buttressed with massive partitions of connective tissue. Scientists have long thought that this organ helps sperm whales to dive deeply to feed. The curved 'basin' atop Leviathan 's snout suggests that it also had a large spermaceti organ, even though it probably did not dive to feed. The authors speculate that, if Leviathan hunted baleen whales near the surface, the large spermaceti organ existed long before modern sperm whales became specialized for foraging squid at depth. The organ could have served other functions, such as echolocation, acoustic displays or aggressive head-butting. "Spermaceti organs could be used as battering rams to injure opponents during contests over females," says evolutionary morphologist David Carrier of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. According to Carrier, at least two nineteenth-century whaling ships were sunk when large males punched holes in their sides with their foreheads, Carrier adds, and Leviathan may have used forehead ramming to dispatch its prey. References1. Lambert, O. et al. Nature 466, 105-108 (2010). Source: www.nature.com/news/2010/100630/full/news.2010.322.html

Additional Resources:New Leviathan Whale Was Prehistoric "Jaws"? (Pictures)'Sea monster' fossil found in Peru desert

|

|

|

|

Post by Life on Aug 4, 2010 1:32:06 GMT 5

The giant bite of a new raptorial sperm whale from the Miocene epoch of PeruThe modern giant sperm whale Physeter macrocephalus, one of the largest known predators, preys upon cephalopods at great depths. Lacking a functional upper dentition, it relies on suction for catching its prey; in contrast, several smaller Miocene sperm whales (Physeteroidea) have been interpreted as raptorial (versus suction) feeders analogous to the modern killer whale Orcinus orca. Whereas very large physeteroid teeth have been discovered in various Miocene localities, associated diagnostic cranial remains have not been found so far. Here we report the discovery of a new giant sperm whale from the Middle Miocene of Peru (approximately 12–13 million years ago), Leviathan melvillei, described on the basis of a skull with teeth and mandible. With a 3-m-long head, very large upper and lower teeth (maximum diameter and length of 12 cm and greater than 36 cm, respectively), robust jaws and a temporal fossa considerably larger than in Physeter, this stem physeteroid represents one of the largest raptorial predators and, to our knowledge, the biggest tetrapod bite ever found. The appearance of gigantic raptorial sperm whales in the fossil record coincides with a phase of diversification and size-range increase of the baleen-bearing mysticetes in the Miocene. We propose that Leviathan fed mostly on high-energy content medium-size baleen whales. As a top predator, together with the contemporaneous giant shark Carcharocles megalodon, it probably had a profound impact on the structuring of Miocene marine communities. The development of a vast supracranial basin in Leviathan, extending on the rostrum as in Physeter, might indicate the presence of an enlarged spermaceti organ in the former that is not associated with deep diving or obligatory suction feeding. Source: www.nature.com/nature/journal/v466/n7302/abs/nature09067.html#supplementary-informationFor full details: click here (PDF download warning)

|

|

|

|

Post by Life on Aug 4, 2010 1:39:58 GMT 5

A killer sperm whale A reconstruction of Leviathan by the artist C. Letenneur Recent fossils are clarifying the emergence of the crown group whales comprised of the toothed whales (odontocetes) and the baleen whales (mysticetes), overall accounting for about 80 species of mammals in today’s water-bodies.. It appears that the basal-most toothed whales are sperm whales, which are a sister-group to the great radiation of “dolphins” (used in the general sense to encompass all the dolphin-like whales including the beaked whales, bottlenose whales, pilot whales, narwhals, belugas and killer whales). Today sperm whales come in two forms: the gigantic big-headed sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) and the miniscule dwarf and pygmy sperm whales (Kogia). Both of these lack teeth on the upper jaw and are suction feeders that suck in squid into their gaping mouths. Several fossil sperm whales where previously described, such as Zygophyseter, Acrophyseter, Orycterocetus and Aprixokogia that appeared to have teeth on both jaws. This suggested that at least some of the basal sperm whales where not suction feeders but probably active macrophagous predators. The new evidence in this regard comes from a clearly macrophagous predatory sperm whale Leviathan melvillei [Footnote 1] from the Miocene of Peru (estimated to be 13.5-17.5 m), which is much larger than the largest ever recorded killer whale (9.8 m). Together with predatory basal baleen whales, like Janjucetus, the characterization of this basal radiation of killer sperm whales is suggesting that the common ancestor of all crown group whales was likely to be an intelligent, raptorial form that was capable of handling large vertebrate prey. The study of these basal toothed whales might also cast some light on the dental predatory specialization of the basal crown whales. Some key questions arise from the characterization of the basal toothed whales of the sperm whale clade (the physeteroids): How do they compare with Janjucetus? Based on this can we reconstruct the dental morphology and its significance for the predatory habits of the ancestor of the crown group whales. Another issue these studies might indirectly relate to pertains to the basal dolphins. The current consensus in whale phylogeny is that the basal most of the “dolphins” are the Platanista species (like the Gangetic shishumAra). Some workers like de Muizon have proposed that these shishumAra-s are a sister group of the extinct squalodontid (like Squalodon and Phoberodon) and the waipatiid dolphins. These shark-toothed dolphins are characterized by a strikingly heterodont dentition – the anterior incisoriform teeth are straight with conical crowns whereas the posterior molariform teeth have broad triangular crown with multiple denticles. Now, workers like Fordyce have proposed that the heterodont condition of these dolphins could be a retention of the primitive heterodont dentition of the archaic whales, the archaeoceti, which are a sister group of all crown group whales. If de Muizon’s phylogenetic hypothesis is correct then the squalodontids and waipatiids are nested inside the crown group whales. So in light of the data from basal physeteroids and mysticetes is de Muizon’s phylogeny still justified? Or did the basal dolphins convergently evolve a dentition resembling the archaeoceti? The story of the killer sperm whales is an old one. The first giant sperm whale teeth were described as such from South Carolina by the great American biologist Leidy in 1877. Subsequently these large teeth have been recovered in several parts of the world suggesting that the large toothed sperm whale was cosmopolitan in distribution. While its bearer remained a mystery, there were other finds which suggested the presence of aggressive predatory sperm whales spanning a whole size range. One of these was Zygophyseter, an approximately 7 meter long Miocene sperm whale described in 2006 by Bianucci et al. At this size and with teeth clearly indicative of carnivory it was likely to have been comparable to the modern killer whale. The other related whale Brygmophyseter (Naganocetus) from Miocene of Japan is also likely to have been a similar sized killer sperm whale. In 2008 Lambert et al described Acrophyseter from the Miocene of Peru, a small sperm whale (around 3-4 meters) with similar predatory adaptations as the former two. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that they lay at the base of the sperm whales clade and represented a Miocene radiation of sperm whales with teeth on both the jaws. The wear facets on their large and robust teeth are particularly telling suggesting that the opposite teeth engage similar to shears to cut out large chunks of flesh from the prey. The more posterior teeth where somewhat laterally flattened suggesting that they might have been used in shearing. However, there was hardly any marked heterodonty that was typical of the basal dolphins and baleen whales archaeocetes. Nevertheless, it was clear that these were no suction feeders like modern sperm whales and are likely to have targeted vertebrates, including their own cousins like dolphins and baleen whales, rather than squids. This list of raptorial sperm whales has now been topped with the brief description of Leviathan by Lambert et al from the Middle Miocene of Peru (12-13 Mya). Finally, provides the face behind the giant sperm whale teeth that have been recorded for more than century now. Skull of this whale is about 3 meters in length with teeth up to 12 cm in diameter and 36 cm in length. At this size Leviathan was about as big as the modern Physeter. However, it was no suction feeder: 1) Its enormous temporal fossa is greater than twice as wide as that of Physeter. 2) Its teeth show comparable wear facets to those seen in the earlier described raptorial sperm whales of the Miocene, but are just much larger. The alveoli suggest that the teeth on the upper jaw had greatly increased procumbency that would have allowed it to engage a convex body wall of large prey. 3) The deep alveoli suggest that the teeth had huge roots to anchor them in place in face large forces exerted by struggling prey. 4) While only a fragment of the mandibular condyle is preserved, the indications are that it was posteriorly located as in the case other sperm whales. This is an indication that the sperm whale mandible was optimized for a wide gape. Further, a comparison of the sperm whale mandibles (E.g. Physeter, Kogia, Zygophyseter and Brygmophyster) indicates that though the condyle is ventrally located in most sperm whales, in the raptorial forms it is particularly robust to deliver a strong bite. The poor preservation in Leviathan obscures its degree of development but there are other indicators of its ability to deliver a strong bite: 5) In Leviathan the face is short relative to Physeter and ratio of width to length of the skull is also high. Thus, in Leviathan we come face to face with one of the largest ever raptorial predators of all times. It was probably larger than Spinosaurus, representatives of which are believed to have exceeded 15 meters in length and was probably only smaller than the larger megalodon sharks (typically estimated at 15-20 meters). However, its bite force was probably the greatest for any vertebrate. Interestingly, giant megalodon sharks also appear in the contemporaneous Miocene formations as Leviathan. The period during which these predators lived saw a major spike in the number of genera of baleen whales. It also marked the first time that the baleen whales started reaching the length of 10 meters and more. Hence, the authors propose that both mega-predators giant megalodon shark and Leviathan might have emerged as a response to the availability of large prey in the form of baleen whales. However, forms like Zygophyseter and Acrophyseter indicate that in the Middle Miocene sperm whales were operating across all the niches of raptorial mammalian marine predators – from around 3m to 18m in length.  Position of the mandibular condyle (after Bianucci et al). (A) Zygophyseter varolai, (B) Naganocetus shigensis, (C) ‘Aulophyseter’ rionegrensis, (D) Physeter macrocephalus, (E) Kogia sima, (F) Kogia breviceps, (G) Mesoplodon bowdoini, (H) Delphinus delphis and (I) Zygorhiza kochii The ventral position of the mandibular condyle and the inferred wide gape of appear to be derived features of the sperm whales – both dolphins and archaeocetes like Zygorhiza have a centrally located mandibular condyle. The other cranial and dental adaptations of the basal Miocene sperm whales indicate that this wide gape specifically evolved in relation to the forceful bite deployed by them in raptorial predation. Later in the Miocene, there appears to have been a dip in the richness of the baleen whales faunas and a global cooling. These events probably correlated with the extinction of the predatory sperm whales. But the crown group sperm whales probably made it through this extinction by reusing the ancestral wide gape for a totally different predatory strategy – i.e. suction feeding to exploit a different food source – the squids. That this strategy probably emerged in the Middle Miocene itself is suggested by Placoziphius, a sperm whale from Europe, which has rudimentary teeth on the upper jaw with no enamel suggesting that they were on their way out. However, the sperm whales were never able to recover the predatory niche vacated by them in the late Miocene extinction. This was instead filled by members the dolphin radiation, the killer whales, which despite being much smaller can slaughter practically any whale in the modern seas.  The head of Physeter showing the highly developed spermaceti organ (after Carrier et al) These basal sperm whales have other implications for sperm whale behavior and biology. Like the extant toothed whales the basal sperm whales have small eyes and a pronounced supracranial basin. This indicates that they used echolocation and like extant sperm whales had a particularly enlarged melon in form of the spermaceti organ. The exact function of this organ remains unclear beyond the role in echolocation that appears to be common to the melons of all toothed whales. While modern sperm whales are not raptorial predators, from the few available records, their behavior might be interpreted as showing atavism of their raptorial past. In an interesting paper published some years ago Carrier et al proposed that the spermaceti organ could be used as a battering ram. They point that there are two reliable records from 1821 and 1851 of Physeter smashing and sinking large ships. In both the incidents the whales were considerably injured by their attackers but were able to sink the ships in deliberate retaliatory strikes. In the 1821 incident a male Physeter first smashed the boat that was used to attack it and then sunk the 238 ton mother ship by breaking its bow with a blow from its head. In the 1851 incident the whale was attacked from three boats and injured, but it crushed two of the boats with its wide gaping jaws (despite having teeth only on the lower jaw). The attackers then pursued it from their ship, to which it turned its attention and struck it twice breaking the bow and sinking the ship in the second strike. The spermaceti organ is further sexually dimorphic with males have a disproportionate expansion of it with increasing body size. Based on this Carrier et al proposed that it might be used in male-male aggression, which is supported by the scars found on the male spermaceti organs. It is possible that it was also used in the past by basal sperm whales in active predation and defense – after all the middle Miocene seas were not a safe place with denizens like the megalodon sharks. The phylogenetic analysis by Lambert et al places Leviathan as a sister group to all the sperm whales (including Placoziphius) except the basal clade comprised of Acrophyseter, Zygophyseter and Brygmophyseter. I suspect it might end up grouping with the above clade if better remains are recovered. Clearly the teeth structure of the basal sperm whales is very different from that of the squalodontids, waipatiids and Janjucetus, all of which retain the heterodonty of their sister group the archaeoceti. They all have characteristic posterior teeth with multiple denticles. Even if the squalodontids and waipatiids are not basal platanistoids, they appear to have several features suggesting that they are still basal dolphins. In light of this it appears that they have retained the primitive dentition, while the basal sperm whales diverged on a distinct trajectory acquiring stout conical-cylindrical teeth. This appears to be a part of the same complex of adaptations that resulted in the ventral movement of the mandibular condyle, with the strong teeth coevolving with the high bit forces. Footnote 1: The species name is after Herman Melville who wrote that famous American neo-epic. Many many yugas ago I was directed by the 1st hero to read that epic, but he lent it to me for a very limited time. I just read a little bit and did not know where the story went. Several years ago ST finally completed the story for me. We agreed that Melville was a neo-mythologian and his name is apt for the new whale. In the mean time I hear that the generic name Leviathan was previously used as synonym for the Mammut and so the ICZN taxomaniacs rule that it is invalid – can we expect anything better from the guys who voted to let Drosophila melanogaster have its name changed? Source: manasataramgini.wordpress.com/2010/07/01/a-killer-sperm-whale/

|

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Feb 12, 2013 23:10:44 GMT 5

Translation of a french article : A whale-eater prehistoric sperm whaleUncovered in Peru, the remains of the whale called Livyatan melvillei are 12 million years old. With huge teeth and powerful jaws, the behemoth could eat whales. Teeth 36 centimeters long and 12 centimeters in diameter within empowered jaws : Livyatan melvillei is equipped to kill. The remains of the 3 meters long skull of this sperm whale that lived 12 million years ago have been discovered in Peru in 2008 by Klaas Post, a Dutch paleontologist with a Belgian colleague, Olivier Lambert, and an Italian researcher, Giovanni Bianucci. The results of their analysis were published Thursday in Nature. "Among the toothed or baleen whales, the skull is actually the fundamental part. The rest of the body is fairly predictable and similar to those of the present species, "says Christian Muizon, co-author of this publication and Director of Earth History department of the National Museum of Natural History. Besides the impressive size of its teeth (the largest teeth of cetaceans had never exceeded 25 centimeters), the skull provided two surprises: the presence of teeth on the upper jaw and a particularly deep temporal fossa. Indeed, the current sperm whales suck their prey, often squids, and do not use their teeth which are limited to a short row on the lower jaw. "Here we have a predator that uses its jaws to hunt. Its temporal muscles are so developed that it could be able to cut in half a dolphin in one single bite, "enthuses Muizon. A 17 meter long behemothThe animal, which at the first look could have measured up to 17 meters, would have been a big whale-eater. "Let us be clear, it could not have tackled a 35 meters blue whale. But there was at that time a large number of small baleen whales specimens measuring between 5 and 7 meters and which were all chosen preys for such a sea monster. "Only the famous megalodon, a giant shark measuring up to 20 meters, could possibly compete with Livyatan melvillei. "But there was enough food for these two behemoths do not have to compete!" jokes the paleontologist. These large predators are indeed usually few in ecosystems. This is what makes the discovery of the skull, and thus of this new species, so extraordinary. To mark the occasion, the name of the new sperm was carefully chosen. In reference to Leviathan sea monster mentioned in the Bible, and melvillei tribute to the author of Moby Dick, Herman Melville. For the moment there is nothing to explain the disappearance of this lineage of whales. Today, there are only three species of whales and all feed by suction. Note : I've modified the genus used at the time Leviathan into Livyatan. www.lefigaro.fr/sciences-technologies/2010/07/02/01030-20100702ARTFIG00651-un-cachalot-prehistorique-mangeur-de-baleines.php |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Jun 27, 2013 4:32:59 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jun 6, 2015 4:23:21 GMT 5

Just a revamp of an earlier post→, but with an image that hopefully remains here as long as the post does:  To get the estimated TL for Livyatan you have to add the condylobasal length, 294cm. This is how we get the original estimate of 1349 cm (50% PI ± 67 cm) and the revised estimate of 1416 (± 52 cm).

original regression:

222.04+4.23*BZW=BL R²=0.72

n=15

revised regression: 69.404+5.342*BZW=BL R²=0.85 n=14

As you see this data point has quite a bit of an impact on the regression and is visibly far from all the others and the regression lines, without it the correlation is also considerably improved. Finally, the average of those estimates directly scaled from each individual in the dataset is 1422cm, and the estimate scaled from the mean values for the sample (mean BZW=153.7cm, mean BL=872.3cm) is 1412cm. ––– Reference:Data from: Lambert, Olivier; Bianucci, Giovanni; Post, Klaas; Muizon, Christian de; Salas-Gismondi, Rodolfo; Urbina, Mario; Reumer, Jelle (2010): The giant bite of a new raptorial sperm whale from the Miocene epoch of Peru. Nature, Vol. 466 (7302) pp. 105-108 Original analysis: coherentsheaf (May 2, 2013 at 11:03pm): theworldofanimals.proboards.com/post/726 |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 5, 2015 18:29:53 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Sept 11, 2015 18:23:28 GMT 5

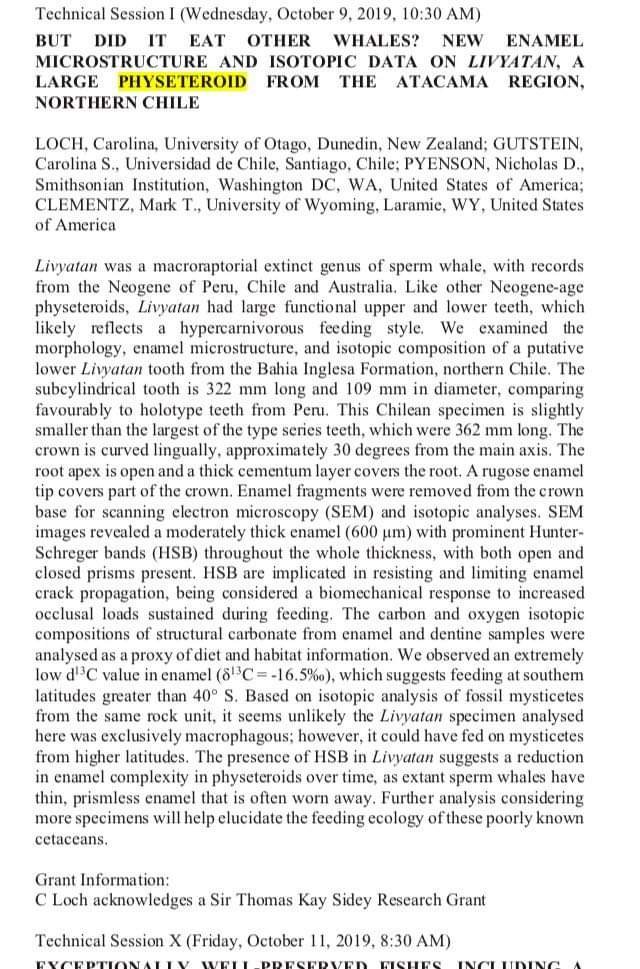

PHYSETEROIDS FROM THE MIOCENE OF PERU: NEW DATA ON

ACROPHYSETER AND LIVYATAN SUPPORTS MACRORAPTORIAL FEEDING

IN SEVERAL EXTINCT SPERM WHALES

LAMBERT, Olivier, Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Brussels,

Belgium; DE MUIZON, Christian, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Paris, France;

URBINA, Mario, Museo de Historia Natural, Lima, Peru; BEATTY, Brian L., NYIT

College of Osteopathic Medicine, New York, NY, United States of America; DI

CELMA, Claudio, University of Camerino, Camerino, Italy; BIANUCCI, Giovanni,

Università di Pisa, Pisa, Italy

With only three extant species, modern sperm whales (Odontoceti, Physeteroidea)

are generally considered as relicts of a previously more diversified clade, originating

during the late Oligocene and reaching its maximum diversity in the Miocene. Displaying

a spectacular size disparity, modern Kogia spp. (pygmy and dwarf sperm whales) and

Physeter (giant sperm whale) share several morphological features (dental reduction,

slender mandibles, and small temporal fossa) correlated to a specialized suction feeding

technique on disphotic to mesopelagic prey.

Although remaining scarce, the fossil record of sperm whales suggests a broader

past ecological diversity; based on cranial and dental characters, several middle to late

Miocene taxa (the medium size Acrophyseter, the large Brygmophyseter and

Zygophyseter, and the giant Livyatan) were tentatively interpreted as macroraptorial

feeders, using massive teeth deeply embedded in robust upper and lower jaws to catch

proportionally large prey.

Together with the study of two new Acrophyseter skulls, a detailed description of the

type material of A. deinodon and L. melvillei (both originating from Miocene levels of the

Pisco Formation, Peru) provides new clues about their hypothetical feeding strategies.

The analysis of the specimens followed different lines: (1) basic craniomandibular

anatomy and comparison; (2) reconstruction of the musculature for adduction/abduction

of the mandibles; (3) bone pathology including the description of buccal maxillary

exostoses in A. deinodon; and (4) tooth wear. Observations and resulting interpretations

point to a feeding technique involving intense use of teeth via powerful bites, contrasting

markedly with the capture technique in both Kogia and Physeter. Placed in a

phylogenetic context, the morphology of the oral apparatus in these macroraptorial sperm

whales is thought to represent a combination of plesiomorphic and derived characters.

Finally, a detailed sedimentological and paleontological analysis of the fossil-rich

localities of Cerro Colorado and Cerro los Quesos yielded a vast amount of data about the

faunas associated to Acrophyseter and Livyatan; the mapping of several hundreds of

marine vertebrate specimens, as well as their positioning along stratigraphic sections,

provides valuable indications about potential prey of these extinct sperm whales.

|

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Sept 28, 2015 2:30:06 GMT 5

Not focused on Livyatan but : Ochyrodon Oxymycterus: Re-description of a Basal Physeteroid (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Miocene of California, and the Evolution of Body Size in Sperm Whales digitalwindow.vassar.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1502&context=senior_capstoneEDIT: "Ontocetus" oxymycterus, redescribed as "Ochyrodon" oxymycterus in Boersma’s recently shared and then removed thesis, has now been officially described as Albicetus oxymycterus. Boersma, Alexandra T.; Pyenson, Nicholas D. (2015): Albicetus oxymycterus , a New Generic Name and Redescription of a Basal Physeteroid (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Miocene of California, and the Evolution of Body Size in Sperm Whales. PLOS ONE 10: e0135551. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135551. journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0135551The content is similar to the prematurely released thesis, but the generic name has been changed and one of Boersma’s advisors coauthored the paper. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Sept 28, 2015 21:52:25 GMT 5

Based on Lambert et al.’s dataset for P. macrocephalus:

With outlier: BZW=11.2791459+0.1179257*TL

Yields a bizygomatic width of 170.40cm at a TL of 1349.35cm. Livyatan has a 15.6% wider head (197cm) than a Physeter of the same length.

Without outlier: BZW=21.5529663+0.1069699*TL

Yields a bizygomatic width of 173.00cm at a TL of 1415.77cm, Livyatan has a 13.9% wider head (197cm) than a Physeter of the same length.

–––Reference:

Lambert, Olivier; Bianucci, Giovanni; Post, Klaas; Muizon, Christian de; Salas-Gismondi, Rodolfo; Urbina, Mario; Reumer, Jelle (2010): The giant bite of a new raptorial sperm whale from the Miocene epoch of Peru. Nature, 466 (7302), pp. 105-108.

|

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Oct 1, 2015 1:43:44 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Jan 14, 2019 14:31:28 GMT 5

FIRST RECORD OF A MACRORAPTORIAL SPERM WHALE (CETACEA,

PHYSETEROIDEA) FROM THE MIOCENE OF ARGENTINA

DAVID SEBASTIÁN PIAZZA

Laboratorio de Anatomía Comparada y Evolución de los Vertebrados. Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales

“Bernardino Rivadavia”, Av. Angel Gallardo 470, (C1405DJR), Buenos Aires, Argentina.

dspiazza@hotmail.com

FEDERICO LISANDRO AGNOLIN

Laboratorio de Anatomía Comparada y Evolución de los Vertebrados. Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales

“Bernardino Rivadavia”, Av. Angel Gallardo 470, (C1405DJR), Buenos Aires, Argentina. Fundación de Historia Natural

“Félix de Azara”. Departamento de Ciencias Naturales y Antropología. Universidad Maimónides.

Hidalgo 775, Buenos Aires, Argentina. CONICET.

fedeagnolin@yahoo.com.ar

SERGIO LUCERO

División Mastozoología, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia Av. Angel Gallardo 470,

(C1405BDB), Buenos Aires, Argentina. CONICET.

serglucero@yahoo.com.ar

ABSTRACT – Raptorial sperm whales of the genus Livyatan

were described from the Miocene of Peru and Chile. Revision of

paleontological collections resulted in the finding of isolated teeth

belonging to aff. Livyatan sp. coming from Early-Middle Miocene

strata from Bajo del Gualicho area, Río Negro Province, Argentina.

These specimens represent the first finding of this genus in the

Southwestern Atlantic Ocean and indicate that Livyatan-like forms

were more widespread than previously thought. The reasons of

the extinction of such predatory whales are still uncertain, but it is

not improbable that it may be correlated with competition for food

resources with globicephaline delphinids. This hypothesis still rests

on weak evidence and should be evaluated through findings of new

specimens, as well as detailed analysis of the fossil record.

Keywords: Livyatan, Macroraptorial sperm-whales, Argentina,

Patagonia, Miocene.

|

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Aug 20, 2019 6:08:43 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Aug 20, 2019 17:22:08 GMT 5

From Lambert, O., Bianucci, G., Post, K., de Muizon, C., Salas-Gismondi, R., Urbina, M. and Reumer, J. 2010. The giant bite of a new raptorial sperm whale from the Miocene epoch of Peru. Nature 466 (7302): 105.: Maxillary tooth diameters: Alveolus R[cm] L[cm]

1 10 9.3

2 - 11.1

4 12.1 11.5

5 11.5 12.2

6 11.5 10.8

7 - 9.6

Mandibular tooth measurements: tooth/position length [cm] max. diameter [cm]

E r1 +31.5 8.1

D r2 +32.5 10.7

F r3 - 11.1

G r4 - +10.4

A r5 +35.7 11.1

B r6 +36 11.1

C r7 +36.1 10.2

H l2-3 +36.2 10.6

I l? +32 +10.2

Alveolar measurements: R Upr L Upr

1 e15 e14.5

2 - -

3 16 -

4 19.7 19.5

5 16.3 18

6 14.9 16

7 - 12

8 10 -

9 e7.4 6.5

R Lwr L Lwr

1 - -

2 12.2 -

3 13.4 12.8

4 13.1 13.1

5 13.4 13.6

6 12.4 13.1

7 12.0 12.1

8 11.5 e12.5

9 11.3 e11.8

10 8.4 +60

11 5.3 -

Note that among the alveoli with preserved teeth or roots there are the ones with the largest diameters, U4-5 and L3-6, so the largest teeth are presumably preserved (at least the roots). The alveoli with the smallest diameters all lack preserved teeth, so a number of smaller teeth likely aren’t preserved. Obviously there must have been smaller or at least thinner teeth in order to fit 53-74mm alveoli. I think we can expect the teeth in these smaller alveoli to have been quite close to their alveolar diameter:  As you see in the largest teeth, the roots are notably smaller than the alveoli, but in smaller teeth, the the teeth occupy more of the alveolus. So presumably, the smallest teeth in the Livyatan holotype would have been similar in diameter to their alveoli, or around 5-8cm. Comparing isolated teeth to only the preserved teeth of the holotype is misleading, as it is clear that some of the missing teeth were smaller than any of the preserved ones. I think this has some more or less obvious implications for evaluating isolated teeth with regard to the size of the owner, discuss here→ (so we can keep the profiles free of discussion).

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Aug 31, 2019 15:54:30 GMT 5

|

|