Post by Infinity Blade on Jun 24, 2014 2:51:51 GMT 5

Thylacine-Thylacinus cynocephalus

A pair of thylacines in a zoo in Washington D.C., c. 1906.

Temporal range: Pliocene-Holocene (4Ma-1936 CE)

Scientific classification

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Metatheria

Infraclass: Marsupialia

Superorder: Australidelphia

Order: Dasyuromorphia

Family: †Thylacinidae

Genus: †Thylacinus

Species: †T. cynocephalus

Description:

The thylacine (T. cynocephalus; "dog-headed pouched one") or Tasmanian tiger or wolf was a species of predatory marsupial of the extinct family Thylacinidae that lived in Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea. It was the largest predatory marsupial (as well as the only thylacinid) that survived into the modern era until its extinction within said period. T. cynocephalus first appeared around 4 million years ago[1], and went extinct 1936 CE.

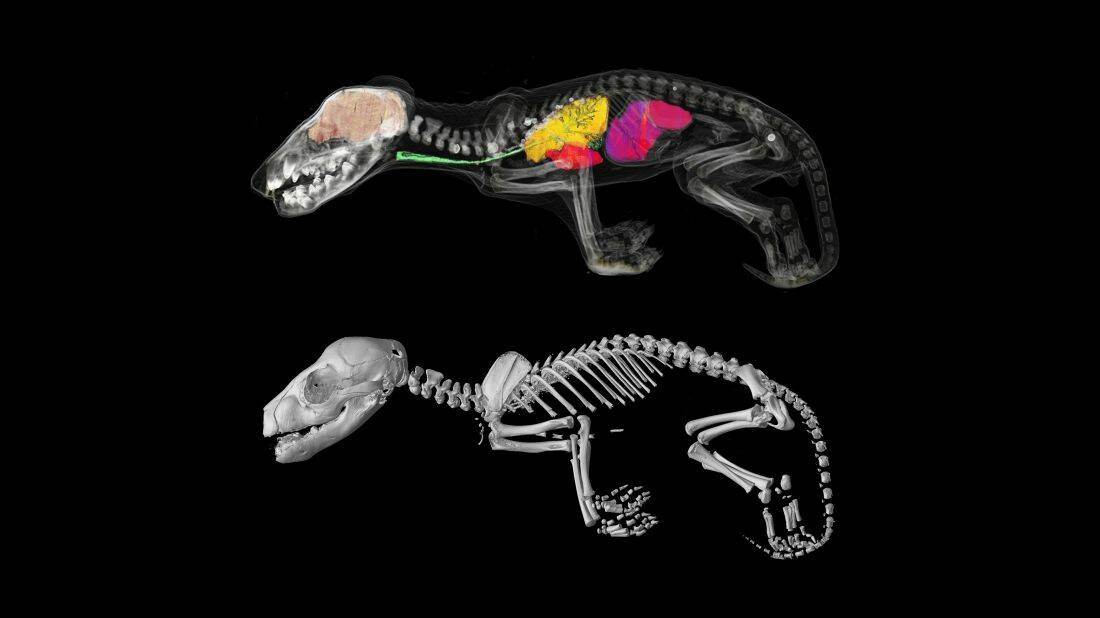

In a way, thylacines and canids are an example of convergent evolution; this is blatantly clear to anyone who physically compares thylacines and canids at first glance, as they share the same basic superficial bauplan. Richard Dawkins notes, "They are easy to tell from a true dog because of the stripes on the back but the skeleton is harder to distinguish. Zoology students at Oxford had to identify 100 zoological specimens as part of the final exam. Word soon got around that, if ever a 'dog' skull was given, it was safe to identify it as Thylacinus on the grounds that anything as obvious as a dog skull had to be a catch. Then one year the examiners, to their credit, double bluffed and put in a real dog skull. The easiest way to tell the difference is by the two prominent holes in the palate bone, which are characteristic of marsupials generally."[2]

Another obvious and well-known feature of the thylacine was the color/pattern of its integument; the thylacine had stripes on the back and rear portion of its body (earning the name "Tasmanian tiger") while the fur was otherwise yellow-brown. Thylacines were 1-1.3 meters long in total body length with the tail being 50-65 centimeters. Furthermore, shoulder height would have been ~60 centimeters and body weights would have been in the range of 20-30 kilograms.[3] Males tended to be larger than females.[4] Life expectancy in the wild was ~5-7 years.[5]

Notwithstanding claims of thylacines having maximum jaw gapes of 120°, this is apparently an exaggeration; their maximum jaw gapes couldn't get any higher than 80°.[6] The aforementioned canids share a similar skull morphology to the thylacine (as said earlier, they are convergent). However, there were some clear differences upon closer inspection. For example, the thylacine's dental formula is 4.1.3.4/3.1.3.4; by contrast a red fox's (Vulpes vulpes) dental formula is 3.1.3.3/3.1.3.3 while that of a grey wolf's (Canis lupus) is 3.1.3.3/3.1.4.3.[7] Likewise, palatal vacuities were present in the skull of the thylacine, the nares were more flared than rectangular (as in placental carnivores), etc.[8]

T. cynocephalus possessed seven cervical, thirteen thoracic, six lumbar, two sacral, and twenty-five caudal vertebrae. The clavicles were narrow, curved, and small (~5cm), which seemingly was one adaptation to cursoriality. Its epipubic bones were yet another feature that was reduced.[9]

Diet and hunting:

Like tigers and wolves from which the animal got two of its names from, it was an apex predator. Prey included the long-nosed potoroo (Potorous tridactylus), eastern bettong (Bettongia gaimardi), eastern barred bandicoot (Perameles gunnii), short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus), red-necked wallaby (Macropus rufogriseus), eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus), common wombat (Vombatus ursinus), Tasmanian pademelon (Thylogale billardierii), and domesticated sheep (Ovis aries).[10] It's been suggested that smaller and more nimble prey would have served as the primary prey of the smaller and more agile females while larger quarry would have been preferable for males. This means that a) prey selection was more diverse with both genders of a single species being specialized for one type of prey and b) intraspecific competition would have been more suppressed when prey was limited.[11] According to Wroe et al. (2005), the thylacine had a rather high bite force quotient.[11][12] The bite force quotient was higher in predators that preyed on larger animals (eg. wolves, African wild dogs, and dingoes). These examples also hunt cooperatively to bring larger prey down and it's been suggested the thylacine would have been intermediate between solitary and pack hunting, being rather fox or jackal-like for small quarry and wolf-like when pack hunting.[11] A 2011 study conducted by Marie Attard et al. concluded that the jaw apparatus of the thylacine was weak to the extent that it would have been specialized in smaller prey (incidentally using this as a possible explanation of its extinction).[13][14] However, as the Thylacine Museum notes, this is in direct contradiction to contemporary accounts claiming that the thylacine indeed hunted sheep and published descriptions of a generalist diet; if Attard et al.'s findings are correct, a few facts regarding sheep must be taken into consideration. Judging from accounts written at the time, thylacines were most threatening during the lambing season; the average body mass for Merino lambs (the breed of choice for early British settlers in Tasmania) up to 90 days old is much smaller than the body mass of an adult, nearly 30 kg thylacine (though, lambs that are 90 days old are not much smaller than this), making them easy prey for even a flimsy-jawed predator. Secondly, when sheep are chased, they will eventually lie down. Dogs have been recorded taking advantage of this idiosyncrasy by easily slaughtering sheep that lie down and do nothing to retaliate; thylacines could have done the same and experienced little to no physical resistance, making any structural weakness of its feeding apparatus irrelevant.[13] Figuierido & Janis (2011) found that T. cynocephalus's elbow joint morphology was most similar to that of ambush predators such as felids than to cursorial ones such as canids[15] although its forelimbs seemed otherwise ill-suited for grappling quarry with the forelimbs. This fact, coupled with a study conducted by the very same authors of the 2011 study three years later, suggests the thylacine was, in actuality, a generalized type of predator that wasn't particularly adapted to either cursorial or ambush hunting.[16]

Extinction:

Thylacines went extinct on the Australian mainland ~3-2k years ago.[17][18] Prowse et al. (2014) found that the introduction of dingoes on Australia during this time could indeed have had some negative impact on the thylacine and Tasmanian devil populations, but the shift in climate coupled with the population growth and technological advancement of humans in Australia seems to have contributed the most to the extinction of the two indigenous marsupial predators in the mainland.[19][20] Although the majority of Australian megafaunal mammals (>90%) went extinct thousands of years earlier in the Pleistocene, the thylacine and grey kangaroo survived and wouldn't disappear from the mainland until later on.[21] Likewise, the last Australian thylacines apparently had a limited genetic diversity.[22] Letnic et al. (2012) even proposed that direct killing by dingoes in agonistic confrontations could have been a way for dingoes to contribute to thylacine extinction on the mainland. Dingoes and male thylacines were similar in size to each other, but females were significantly smaller. Because of this, plus how predators often kill smaller predators and limit their populations, it was proposed that dingoes killing smaller female thylacines could have contributed to extinction, although it was admitted that attributing the extinction to a sole factor is problematic.[23]

The thylacine was attributed to the deaths of domestic sheep in Tasmania, and so bounties were placed on it.[24][25] Hunting, competition with introduced wild dogs, habitat loss, apprehension of animals for zoos[26][27], and a distemper-like disease[28] all contributed to the rarity of the thylacine in Tasmania. On Tuesday, May 6, 1930, Wilfred Batty killed the last recorded wild thylacine (attacking his poultry) in Mawbanna.[29] On September 7, 1936, the last known thylacine (now commonly referred to as "Benjamin"[30]) died in the Beaumaris Zoo.[31] The thylacine wasn't declared extinct until half a century subsequent to "Benjamin's" death due to a 50 year criteria for the declaration of an animal's extinction (which incidentally no longer exists).[31] Sightings on both the mainland and Tasmania have occurred since "Benjamin's" death, but none are confirmed.[32] The thylacine is now a subject of cloning and de-extinction.[33]

References:

[1] web.archive.org/web/20090602070740/http://www.amonline.net.au/thylacine/08.htm

[2] Richard Dawkins (2004). The Ancestor's Tale.

[3] Sally Bryant & Jean Jackson (1999). Tasmania's Threatened Fauna Handbook pg. 190-193.

[4] "Character displacement in Australian dasyurid carnivores: size relationships and prey size patterns" (Jones, 1997).

[5] www.parks.tas.gov.au/index.aspx?base=4765

[6] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/anatomy/external/external_anatomy_2.htm

[7] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/anatomy/skullandskeleton/dentition/dentition_1.htm

[8] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/anatomy/skullandskeleton/skull/skull_1.htm

[9] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/anatomy/skullandskeleton/skeleton/skeleton_1.htm

[10]

www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/behaviour/behaviour_1.htm

[11]

www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/behaviour/behaviour_2.htm

[12] "Bite club: comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behavior in fossil taxa" (Wroe et al., 2005).

[13]

www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/behaviour/behaviour_4.htm

[14] "Skull mechanics and implications for feeding behaviour in a large marsupial carnivore guild: the thylacine, Tasmanian devil and spotted-tailed quoll" (Attard et al., 2011).

[15] "The predatory behaviour of the thylacine: Tasmanian tiger or marsupial wolf?" (Figuierido & Janis, 2011).

[16] "Forelimb anatomy and the discrimination of the predatory behavior of carnivorous mammals: The thylacine as a case study" (Figuierido & Janis, 2014).

[17] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/introducing/whatis/what_is_a_thylacine_1.htm

[18] Paddle (2000). pp. 23-24.

[19] www.australiangeographic.com.au/news/2013/09/dingoes-cleared-of-mainland-extinctions/

[20] "An ecological regime shift resulting from disrupted predator–prey interactions in Holocene Australia" (Prowse et al., 2014).

[21] "Timing and dynamics of Late Pleistocene mammal extinctions in southwestern Australia" (Prideaux et al., 2010).

[22] "Limited Genetic Diversity Preceded Extinction of the Tasmanian Tiger" (Menzies et al., 2012).

[23] "Could Direct Killing by Larger Dingoes Have Caused the Extinction of the Thylacine from Mainland Australia?" (Letnic et al., 2012).

[24] www.parks.tas.gov.au/index.aspx?base=4765

[25] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/persecution/persecution_1.htm

[26] "Canine Revolution: The Social and Environmental Impact of the Introduction of the Dog to Tasmania" (Boyce, 2006).

[27] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/extvssurv/extinction_vs_survival_5.htm

[28] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/extvssurv/extinction_vs_survival_2.htm

[29] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/persecution/persecution_10.htm

[30] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/captivity/Benjamin/Benjamin_1.htm

[31] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/extvssurv/extinction_vs_survival_1.htm

[32] www.arkive.org/thylacine/thylacinus-cynocephalus/video-00.html

[33] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/mrp/cloning/cloning_1.htm

A pair of thylacines in a zoo in Washington D.C., c. 1906.

Temporal range: Pliocene-Holocene (4Ma-1936 CE)

Scientific classification

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Metatheria

Infraclass: Marsupialia

Superorder: Australidelphia

Order: Dasyuromorphia

Family: †Thylacinidae

Genus: †Thylacinus

Species: †T. cynocephalus

Description:

The thylacine (T. cynocephalus; "dog-headed pouched one") or Tasmanian tiger or wolf was a species of predatory marsupial of the extinct family Thylacinidae that lived in Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea. It was the largest predatory marsupial (as well as the only thylacinid) that survived into the modern era until its extinction within said period. T. cynocephalus first appeared around 4 million years ago[1], and went extinct 1936 CE.

In a way, thylacines and canids are an example of convergent evolution; this is blatantly clear to anyone who physically compares thylacines and canids at first glance, as they share the same basic superficial bauplan. Richard Dawkins notes, "They are easy to tell from a true dog because of the stripes on the back but the skeleton is harder to distinguish. Zoology students at Oxford had to identify 100 zoological specimens as part of the final exam. Word soon got around that, if ever a 'dog' skull was given, it was safe to identify it as Thylacinus on the grounds that anything as obvious as a dog skull had to be a catch. Then one year the examiners, to their credit, double bluffed and put in a real dog skull. The easiest way to tell the difference is by the two prominent holes in the palate bone, which are characteristic of marsupials generally."[2]

Another obvious and well-known feature of the thylacine was the color/pattern of its integument; the thylacine had stripes on the back and rear portion of its body (earning the name "Tasmanian tiger") while the fur was otherwise yellow-brown. Thylacines were 1-1.3 meters long in total body length with the tail being 50-65 centimeters. Furthermore, shoulder height would have been ~60 centimeters and body weights would have been in the range of 20-30 kilograms.[3] Males tended to be larger than females.[4] Life expectancy in the wild was ~5-7 years.[5]

Notwithstanding claims of thylacines having maximum jaw gapes of 120°, this is apparently an exaggeration; their maximum jaw gapes couldn't get any higher than 80°.[6] The aforementioned canids share a similar skull morphology to the thylacine (as said earlier, they are convergent). However, there were some clear differences upon closer inspection. For example, the thylacine's dental formula is 4.1.3.4/3.1.3.4; by contrast a red fox's (Vulpes vulpes) dental formula is 3.1.3.3/3.1.3.3 while that of a grey wolf's (Canis lupus) is 3.1.3.3/3.1.4.3.[7] Likewise, palatal vacuities were present in the skull of the thylacine, the nares were more flared than rectangular (as in placental carnivores), etc.[8]

T. cynocephalus possessed seven cervical, thirteen thoracic, six lumbar, two sacral, and twenty-five caudal vertebrae. The clavicles were narrow, curved, and small (~5cm), which seemingly was one adaptation to cursoriality. Its epipubic bones were yet another feature that was reduced.[9]

Diet and hunting:

Like tigers and wolves from which the animal got two of its names from, it was an apex predator. Prey included the long-nosed potoroo (Potorous tridactylus), eastern bettong (Bettongia gaimardi), eastern barred bandicoot (Perameles gunnii), short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus), red-necked wallaby (Macropus rufogriseus), eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus), common wombat (Vombatus ursinus), Tasmanian pademelon (Thylogale billardierii), and domesticated sheep (Ovis aries).[10] It's been suggested that smaller and more nimble prey would have served as the primary prey of the smaller and more agile females while larger quarry would have been preferable for males. This means that a) prey selection was more diverse with both genders of a single species being specialized for one type of prey and b) intraspecific competition would have been more suppressed when prey was limited.[11] According to Wroe et al. (2005), the thylacine had a rather high bite force quotient.[11][12] The bite force quotient was higher in predators that preyed on larger animals (eg. wolves, African wild dogs, and dingoes). These examples also hunt cooperatively to bring larger prey down and it's been suggested the thylacine would have been intermediate between solitary and pack hunting, being rather fox or jackal-like for small quarry and wolf-like when pack hunting.[11] A 2011 study conducted by Marie Attard et al. concluded that the jaw apparatus of the thylacine was weak to the extent that it would have been specialized in smaller prey (incidentally using this as a possible explanation of its extinction).[13][14] However, as the Thylacine Museum notes, this is in direct contradiction to contemporary accounts claiming that the thylacine indeed hunted sheep and published descriptions of a generalist diet; if Attard et al.'s findings are correct, a few facts regarding sheep must be taken into consideration. Judging from accounts written at the time, thylacines were most threatening during the lambing season; the average body mass for Merino lambs (the breed of choice for early British settlers in Tasmania) up to 90 days old is much smaller than the body mass of an adult, nearly 30 kg thylacine (though, lambs that are 90 days old are not much smaller than this), making them easy prey for even a flimsy-jawed predator. Secondly, when sheep are chased, they will eventually lie down. Dogs have been recorded taking advantage of this idiosyncrasy by easily slaughtering sheep that lie down and do nothing to retaliate; thylacines could have done the same and experienced little to no physical resistance, making any structural weakness of its feeding apparatus irrelevant.[13] Figuierido & Janis (2011) found that T. cynocephalus's elbow joint morphology was most similar to that of ambush predators such as felids than to cursorial ones such as canids[15] although its forelimbs seemed otherwise ill-suited for grappling quarry with the forelimbs. This fact, coupled with a study conducted by the very same authors of the 2011 study three years later, suggests the thylacine was, in actuality, a generalized type of predator that wasn't particularly adapted to either cursorial or ambush hunting.[16]

Extinction:

Thylacines went extinct on the Australian mainland ~3-2k years ago.[17][18] Prowse et al. (2014) found that the introduction of dingoes on Australia during this time could indeed have had some negative impact on the thylacine and Tasmanian devil populations, but the shift in climate coupled with the population growth and technological advancement of humans in Australia seems to have contributed the most to the extinction of the two indigenous marsupial predators in the mainland.[19][20] Although the majority of Australian megafaunal mammals (>90%) went extinct thousands of years earlier in the Pleistocene, the thylacine and grey kangaroo survived and wouldn't disappear from the mainland until later on.[21] Likewise, the last Australian thylacines apparently had a limited genetic diversity.[22] Letnic et al. (2012) even proposed that direct killing by dingoes in agonistic confrontations could have been a way for dingoes to contribute to thylacine extinction on the mainland. Dingoes and male thylacines were similar in size to each other, but females were significantly smaller. Because of this, plus how predators often kill smaller predators and limit their populations, it was proposed that dingoes killing smaller female thylacines could have contributed to extinction, although it was admitted that attributing the extinction to a sole factor is problematic.[23]

The thylacine was attributed to the deaths of domestic sheep in Tasmania, and so bounties were placed on it.[24][25] Hunting, competition with introduced wild dogs, habitat loss, apprehension of animals for zoos[26][27], and a distemper-like disease[28] all contributed to the rarity of the thylacine in Tasmania. On Tuesday, May 6, 1930, Wilfred Batty killed the last recorded wild thylacine (attacking his poultry) in Mawbanna.[29] On September 7, 1936, the last known thylacine (now commonly referred to as "Benjamin"[30]) died in the Beaumaris Zoo.[31] The thylacine wasn't declared extinct until half a century subsequent to "Benjamin's" death due to a 50 year criteria for the declaration of an animal's extinction (which incidentally no longer exists).[31] Sightings on both the mainland and Tasmania have occurred since "Benjamin's" death, but none are confirmed.[32] The thylacine is now a subject of cloning and de-extinction.[33]

References:

[1] web.archive.org/web/20090602070740/http://www.amonline.net.au/thylacine/08.htm

[2] Richard Dawkins (2004). The Ancestor's Tale.

[3] Sally Bryant & Jean Jackson (1999). Tasmania's Threatened Fauna Handbook pg. 190-193.

[4] "Character displacement in Australian dasyurid carnivores: size relationships and prey size patterns" (Jones, 1997).

[5] www.parks.tas.gov.au/index.aspx?base=4765

[6] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/anatomy/external/external_anatomy_2.htm

[7] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/anatomy/skullandskeleton/dentition/dentition_1.htm

[8] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/anatomy/skullandskeleton/skull/skull_1.htm

[9] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/anatomy/skullandskeleton/skeleton/skeleton_1.htm

[10]

www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/behaviour/behaviour_1.htm

[11]

www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/behaviour/behaviour_2.htm

[12] "Bite club: comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behavior in fossil taxa" (Wroe et al., 2005).

[13]

www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/biology/behaviour/behaviour_4.htm

[14] "Skull mechanics and implications for feeding behaviour in a large marsupial carnivore guild: the thylacine, Tasmanian devil and spotted-tailed quoll" (Attard et al., 2011).

[15] "The predatory behaviour of the thylacine: Tasmanian tiger or marsupial wolf?" (Figuierido & Janis, 2011).

[16] "Forelimb anatomy and the discrimination of the predatory behavior of carnivorous mammals: The thylacine as a case study" (Figuierido & Janis, 2014).

[17] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/introducing/whatis/what_is_a_thylacine_1.htm

[18] Paddle (2000). pp. 23-24.

[19] www.australiangeographic.com.au/news/2013/09/dingoes-cleared-of-mainland-extinctions/

[20] "An ecological regime shift resulting from disrupted predator–prey interactions in Holocene Australia" (Prowse et al., 2014).

[21] "Timing and dynamics of Late Pleistocene mammal extinctions in southwestern Australia" (Prideaux et al., 2010).

[22] "Limited Genetic Diversity Preceded Extinction of the Tasmanian Tiger" (Menzies et al., 2012).

[23] "Could Direct Killing by Larger Dingoes Have Caused the Extinction of the Thylacine from Mainland Australia?" (Letnic et al., 2012).

[24] www.parks.tas.gov.au/index.aspx?base=4765

[25] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/persecution/persecution_1.htm

[26] "Canine Revolution: The Social and Environmental Impact of the Introduction of the Dog to Tasmania" (Boyce, 2006).

[27] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/extvssurv/extinction_vs_survival_5.htm

[28] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/extvssurv/extinction_vs_survival_2.htm

[29] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/persecution/persecution_10.htm

[30] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/captivity/Benjamin/Benjamin_1.htm

[31] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/history/extvssurv/extinction_vs_survival_1.htm

[32] www.arkive.org/thylacine/thylacinus-cynocephalus/video-00.html

[33] www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/mrp/cloning/cloning_1.htm