|

|

Post by theropod on May 28, 2013 2:22:03 GMT 5

I stay on my position of the scientifical observations made regarding these carnosaurs teeth, Coria whole statement was not based on a comparison with Rex and you can found others similar statements elsewhere. Carnosaurs were not brutish feeders. The comparison with sharks does not change anything, the great white is justly acknowledged to be a cautious attacker and feeder. Based on studies of cranial strenght, neck musculature, comparison with extant analogies for (tooth-)Morphology and function, carnosaurs likely generated immense forces while feeding. There is no point in having a tremendously strong cranium if you only nipped at your prex. There is no reason to suspect Carcharodontosaurs were that drastically different from Allosaurids. see the post on A. fragilis/jimmadseni for the data (page 1). Extant slicers are no cautious feeders with tremendously fragile teeth. Coria, just like Wroe, was speaking in relative terms. Otherwise, give me a study suggesting Allosaur teeth to have been "very weak". I haven't found any rigorous scientific metods suggesting that so far. That his statement was in a comparisonal context with T. rex is the most parsimonous, if not the only valid scenario for him stating this. |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on May 28, 2013 3:02:46 GMT 5

I don't argue the teeth were exceptionally fragile or so, I say they were not robust feeders and their dentition was somewhat gracile, which is actually their evolutionary advantage.

That was this misinterpreted, implausible extended comparison with white shark teeth which I criticized initially.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 28, 2013 15:06:47 GMT 5

I argue they were not particularly delicate, as demonstrated by that comparison and others. Therefore these claims are wrong, and they are what is misinterpeeted all the time. Carnosaur teeth were not that delicate, of course not made for crushing bone, but at least as robust as shark-teeth, and could have endured considerable stresses during feeding, contrary to the widespread opinion their bites were ineffective.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 28, 2013 17:58:13 GMT 5

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.20563/full onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.20563/fullI will elaborate a bit on this comparison from Snively et al., 2007. I recommend reading the paper, it gives a fantastic overview to neck musculature in large, macropredatory theropods, a subject whose details tend to get overlooked by many. Mere interpretations are set after a question mark. 1) Tyrannosaur: T. rexPuncture-, crush- and possibly shake- feeder, ?Mid-sized/armoured prey specialist massive skull with massive adductor muscles and large, robust but blunt teeth, comparatively small gape and depressor muscles,thick, short neck for weight support, prominent lateral (complexus, splenius capitis, longissimus capitis superficialis*) and dorsal muscles (transversospinalis capitis), atrophied attachments of head depressors, levers primarily in lateral direction Built to hold onto prey comparatively long, bite down with tremendous force and shake/twist to break bones and pull on it while feeding to rip off chunks 2) Allosaurid: A. fragilisstrike-, pull- and tear-feeder, ?generalist predator of small to giant prey animals. lightweight, narrow and compact skull, wide gape in exchange for weak bite force (rostrocaudally short adductor muscles), comparatively short, narrow teeth, specialization in head depression, neck ventroflexion and pulling, long cervical collumn with highly mobile vertebrae, moderate-sized lateral muscles (complexus, splenius capitis), prominent dorsi- (transversospinalis cranialis) and ventroflexive (longissimus capitis profundus/superficialis, rectus capitis, iliocostalis capitis) muscles and moment arms, attachments primarily dorsoventral Built to slash/strike at or push into prey (massive application of cervical force via the toothrow to cause deep injuries) and pull, primarily exanguination of soft tissues by sharp but short sawlike dentition 3) Neoceratosaur: C. nasicornisspecialised, large skulled, long toothed slicer, ?medium-sized prey specialist Large, narrow skull size, very long, laterally compressed teeth, well developed moment arms for dorsiflexion and ventroflexion, particularly strong dorsi/lateroflexion implied for M. complexus, strong ventroflexive moment arms for longissimus capitis profundus, shorter ones for rectus capitis and l. cap. superficialis, neck muscles less specialized than in Allosauridae or Tyrannosauridae, but generally well-developed, Primarily damaging due to long maxillary teeth faciliating deep bites without particular reinforcement ReferencesThis is a rough summary of: onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.20563/fullelaborated interpretation of and literature on Allosaurus: theworldofanimals.proboards.com/post/1011*in T. rex this is a primarily lateroflexive lever arm, in A. fragilis a ventroflexive one |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on May 28, 2013 19:19:34 GMT 5

I argue they were not particularly delicate, as demonstrated by that comparison and others. Therefore these claims are wrong, and they are what is misinterpeeted all the time. Carnosaur teeth were not that delicate, of course not made for crushing bone, but at least as robust as shark-teeth, and could have endured considerable stresses during feeding, contrary to the widespread opinion their bites were ineffective. I'm fine with this, nobody argues that they would break like glass at the first contact with a hard structure, only that they are not particularly robust. And I add that the comparisons with white sharks teeth robustness is complicated by numerous evolutionnary and specific factors. |

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on May 28, 2013 23:23:11 GMT 5

I will now quote the next few sentences, to complete the information about feeding apparata showing there: |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 29, 2013 0:23:36 GMT 5

Thanks, that completes the picture, and matched what I think myself on the issue of bite force as a predictor or predatory success among different taxa.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 29, 2013 0:32:33 GMT 5

I would be interested in maximum gape angles among predators.

There is a payoff between adductor size/leverage (rostroterminal lenght of lower temporal fenestra/rostroterminal position of attachments) and gape. Furthermore some animals show specific adaptions in the jaw joint to allow for a wide opening-angle, and longer jaws of course increase the functional gape.

Can anyone share more precise data on the variation of these factors among extant and extinct carnivores?

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 29, 2013 21:26:46 GMT 5

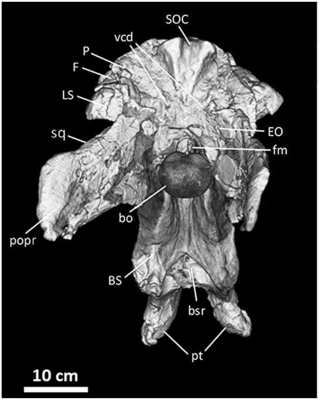

One update about neck muscles in Carcharodontosaurs:  This is the braincase in Acrocanthosaurus atokensis. herefor comparison see the supraoccipital-parietal region of Allosaurus and Daspletosaurus hereIt appears there is a considerable lever arm for ventroflexion in this case too, however it is somewhat less marked than in Allosaurus. The paroccipital processes face ventrolaterally, but not quite as far ventrally as in Allosaurus, and much further posteriorly. There don't seem to be as marked basitubera. I think during their evolution Carcharodontosaurs specialized more and relied more on longer jaws and toothrows than on depressor-forces (comparable to my above interpretation of Ceratosaurus but for gigantophagy), however pulling forces probably still played an important role in their feeding. C. iguidensis looks not too different than Acrocanthosaurus. In both the paroccipitals are well-developed and reach far back posteriorly. Those in Giganotosaurus are seemingly shorter and not as broad, so this is arguably a taxon with a smaller role of cervical activity during feeding. The orientation is similar in all of them. from Bakker, 1998 Confirming my theory, altough Bakker seems to think of a different reason for it; imo it's most likely carcharodontosaurs did not specialize in using their neck muscles but rather their longer teeth and bigger jaws, but just as much for Gigantophagy. Indeed, now we know they coexisted with huge sauropods. |

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on May 30, 2013 0:17:47 GMT 5

I will now quote my post in the crushing vs slicing therad, because I think it is relevant here:

P.P.S. theropod, I'm sorry if you don't like, when an old post of you is quoted, but there is nothing wrong with your post, so I did it.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 30, 2013 23:01:36 GMT 5

I tought it is your post (supposedly from carnivora)? Anyway, nothing wrong with quoting old posts, that can be very useful at times.

Every animal has to perform some degree of both. Even the strongest bite is useless if it is distributed over too large an area (more concrete: too blunt or no teeth). Even the sharpest teeth are useless if no force is applied (no musculature present). Depending on the morphology, these two variables balance out each other (higher bite forces require less sharp teeth/sharper teeth lower bite forces) in animals adapted to macropredatory behaviour using their jaws as primary weapons of damage-dealing.

Many animals are forced to engage in a compromise between the ideal dentition for their respective specialization and physiological or phylogenetic factors (eg. carnivorans are unlikely to develop a lizard-like slicing dentition because of their general bauplan and missing tooth replacement, Sharks are unlikely to develop a croc-like crushing dentition because of their kinetic skeleton and relatively loose teeth), this is the reason for the fantastic variance we can see among animal jaws and teeth.

Both hold certain advantages, in the case of crushing, mostly against armour or bone, due to higher tooth robusticity (lower risk of shattering), and in using the mouth as a mean of controlling something, in the case of slicing, greater efficiency and effectiveness in severing (fibrous) soft tissue (due to less force being needed for it), ability to more quickly and economically cause damage, greater gape and often a less massive skull and the resulting faster strike.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on May 30, 2013 23:09:20 GMT 5

It is my post, but the sentence I agree with is yours.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on May 31, 2013 2:37:43 GMT 5

Luckily one of the old quotes of mine that still hold true, no 16m Giganotosaurus in there  |

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on May 31, 2013 19:29:02 GMT 5

This quote is was made in September I think, so after that time.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jun 1, 2013 0:34:37 GMT 5

On carnivora, I today posted this paper, when Tyrannosaurus' slicing skill were discussed: Tyrannosaurus rex and other tyrannosaurid theropods exerted high bite forces, and large muscle attachments suggest that the tyrannosaurid neck was a concomitantly powerful component of the feeding apparatus. We examine accelerative and work-generating capacity (WGC) of neck muscles in adult Tyrannosaurus rex, using a 3-D vector-based method that incorporates aspects of muscle force generation, reconstruction of muscle morphology and moment arms, and rotational inertias of the head and neck. Under conservative assumptions, radial accelerations of the head by large superficial muscles (M. transversospinalis capitis, M. complexus, and M. longissimus capitis superficialis) enabled rapid gaze shifts and imparted high tangential velocities to food sufficient for inertial feeding. High WGC by these and deeper muscles under eccentric contraction indicate high efficacy for tearing flesh, especially with the head and neck in an extended posture. Sensitivity analyses suggest that assigned density of the antorbital region has substantial effects on calculated rotational inertia, and hence on the accuracy of results. However, even with high latitude for es- timation errors, the results indicate that adult T. rex could strike rapidly at prey and engage in complexly modulated inertial feeding, as seen in extant archosaurs.www.bio.ucalgary.ca/contact/faculty/pdf/russell/305.pdf |

|