|

|

Post by theropod on Jun 1, 2013 2:37:23 GMT 5

From what I read they suggest it did this by inertial feeding (shaking). It is debatable whether I would call this slicing. snively et al., 2013 also stated the tearing action was more notable in Allosaurs, rather comparing tyrannosaurs to crocodilians. EDIT: and Studies considering tooth morphology found Tyrannosaur teeth to be ineffective slicing tools.

The neck muscles also seem to show a clear function of controlling prey with the mouth (Snively & Russel suggest, they lacked the functional forelimbs other theropods would have used)

Overall, tyrannosaurs unsurprisingly seem to have complemented their broader, blunter teeth by using raw power while feeding, the same is seen in crocodilians, used as an analogy by the authors (of course those lack cutting edges and hence are no ideal analogy, but the difference should be clear).

Thanks for posting!

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jun 1, 2013 11:46:39 GMT 5

I don't think crocodiles are a good comparison. Tyrant has compared their teeth on CF and the ones of Tyrannosaurus were sharper than the ones of crocodiles. Coherenstsheaf also said that the crushing of crocodiles and Tyrannosaurus may have been a bit different: carnivoraforum.com/single/?p=8408855&t=9755970 |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jun 1, 2013 15:01:29 GMT 5

"(of course those lack cutting edges and hence are no ideal analogy, but the difference should be clear)"

That's what I wrote.

Their teeth are not the same. They are just an analogy for the feeding style, requiring a lot of strenght.

The crushing of T. rex seems base on long teeth, going deep and effectively breaking bones without additional help. In crocodilians, the teeth are rather for gripping and most of the damage is done by deathrolls or shaking, or simply drowning.

While feading, logically T. rex rather relies on raw power to tear pieces off its prey, contrary to animals with primarily slicing jaws.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jun 12, 2013 22:24:03 GMT 5

Source: Young MT, Brusatte SL, de Andrade MB, Desojo JB, Beatty BL, et al. (2012) The Cranial Osteology and Feeding Ecology of the Metriorhynchid Crocodylomorph Genera Dakosaurus and Plesiosuchus from the Late Jurassic of Europe. In: PLoS ONE 7(9): e44985. p. 1-42 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044985

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jun 15, 2013 16:35:02 GMT 5

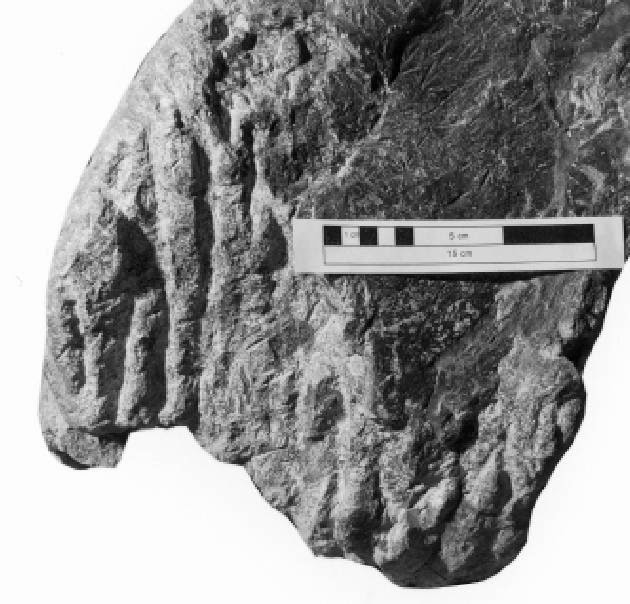

On the myth of slicers*, be it dinosaurs, lizards or sharks, avoiding bony regions at all costs: Hone, D.W.E. & Rauhut, O.W.M. 2009: Feeding behaviour and bone utilization by theropod dinosaurs. Lethaia, 10.1111/j.1502-3931.2009.00187.x www.bio.utk.edu/biologyinbox/unit1/readings/Hone%20&%20Rauhut%202009%20-%20Feeding%20behaviour%20and%20bone%20utilization%20by%20theropod%20dinosaurs.pdfAs a little demonstration, the ilium of a Camarasaurus from the Morrison Formation, bearing bite marks supposedly made by the premaxillary teeth of a theropod, supposedly Allosaurus (likely going by its abundance). Note such bite marks are not very common, not even in Tyrannosaurs, but Camarasaurus was not only supposedly much larger than the animal that left the bite marks, but the ilium is also among the largest and most robust bones in a dinosaur skeleton.  *Hereby defined as animals with comparatively thin, "delicate" teeth relying primarily on soft-tissue evisceration and comparatively low bite forces *Hereby defined as animals with comparatively thin, "delicate" teeth relying primarily on soft-tissue evisceration and comparatively low bite forces |

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jun 19, 2013 16:26:32 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jun 19, 2013 16:44:46 GMT 5

The "cracking teeth" debate is long over, but I have to quote an old post, because I made an error: Theropod, it seems like Grey's opinion isn't very different from yours, because the quote of Kent says pretty much the same as you say: Source: issue 2190 of New Scientist magazine, 12 June 1999, page 32 Maybe he ment being ripped out by saying "being cracked". I admit I should have read "Hell's teeth" more carefully, before using it as a source:The cracking issue was indeed mentioned in the article. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jun 19, 2013 16:46:49 GMT 5

Unlikely in this regard means "less likely than in Carcharodon", just to clarify that.

It is the reference point it is nearly always compared to, instead of comparing it to a wider variaty of animals. Some functional analysis of large predator teeth would be really nice, too many myths and loose interpretations are floating around, including that some equate Carcharocles with T. rex as regards their tooth function...

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jun 19, 2013 16:48:14 GMT 5

I didn't want to say that I necessarily support Grey's view, I simply wanted to point out my mistake.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jun 30, 2013 1:53:27 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 4, 2013 1:51:26 GMT 5

Scientists have analysed how an extinct sabretooth animal with huge canines dispatched its prey, finding that strong neck muscles were vital for securing a kill.

The marsupial, which terrorised South America 3.5 million years ago, had the biggest canine teeth for its size. Experts say the big beast possessed extreme adaptations to the "sabretooth lifestyle". The killing behaviour of Thylacosmilus atrox, is described in Plos One. Until now, the extinct sabretooth "tiger" Smilodon fatalis has received most attention as a ferocious sabretooth predator. But millions of years earlier, a pouched marsupial was one of dozens of sabretooth beasts that had roamed the Earth before the better known killer Smilodon, which went extinct at the end of the last Ice Age. Like Smilodon, Thylacosmilus had highly specialised canines adapted to kill large beasts but until now little was known about the exact way it killed its prey. Scientists took CT scans of fossil remains to construct high-resolution digital 3D models of both sabretooth beasts, and compared them to the modern leopard. The simulations were digitally loaded with forces to see how the animals would have behaved when biting and killing prey. Weak biteThe work was led by Stephen Wroe from the University of New South Wales, Australia, who explained that Thylacosmilus's closest living relatives are Australian and American marsupials. "We found that both sabretooth species were similar in possessing weak jaw muscle driven bites compared to the leopard, but the mechanical performance of the sabretooths' skulls showed that they were both well-adapted to resist forces generated from very powerful neck muscles," said Dr Wroe, who led the research. For its size - Thylacosmilus's huge canine teeth were larger than those of any other known sabretooth. The roots of these canines went back to within millimetres of its very small brain case. " Thylacosmilus was even more extreme. Its skull easily outperformed that of the placental Smilodon and was much better adapted to resist forces incurred by a neck-driven bite." This adaptation was vital as its long thin canines were vulnerable to snapping. To hunt, the animal had to secure and immobilise large prey using its powerful forearms before inserting its long canines into the windpipe or major arteries of the neck - "a mix of brute force and delicate precision". Fragile teethThese adaptations allowed for a relatively rapid kill of dangerous big prey. "The bottom line is that the huge sabres of Thylacosmilus were driven home by the neck muscles alone - and - because the teeth were actually quite fragile - this must have been achieved with surprising precision. "It may not have been the smartest of mammalian super-predators - but in terms of specialisation - Thylacosmilus took the already extreme sabretooth lifestyle to a whole new level, which clearly exceeded that of the much better known sabretooth tiger." Source : www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-23126270Plos One paper : www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0066888 When will people learn it? ;D That reminds me, what creature posted above about Lycaenops suggests a slashing bite for it, and it too has sabre teeth. Seems to go in the same direction. |

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jul 12, 2013 19:07:39 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jul 12, 2013 23:07:54 GMT 5

Bardet N, Jalil N-E, de Lapparent de Broin F, Germain D, Lambert O, et al. (2013) A Giant Chelonioid Turtle from the Late Cretaceous of Morocco with a Suction Feeding Apparatus Unique among Tetrapods. In: PLoS ONE 8(7): e63586. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063586 |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 16, 2013 15:14:21 GMT 5

faculty.cns.uni.edu/~spradlin/SandE/Readings/dinos%20PAL_E2427.pdfResumed evidence for bone puncturing, shattering and osteophagy in Tyrannosaurus, analysis of the purpose of its teeth and the "shock-absorber". Another thing (which I found in The Dinosauria): Tyrannosaur teeth and serrations were functionally comparable to "a dull, smooth blade" (?probably an adaption for edge durability), not other serrated teeth like those of C. carcharias (Abler, 1992/2001; I didn't attempt to search through the hundreds of pages of references but I can look for the name of the paper if someone is interested). A comparison with some other ziphodont taxa would be interesting, particularly between more or less robust ones, since this should help asessing the purpose of the teeth.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Oct 9, 2013 20:40:03 GMT 5

|

|