|

|

Post by Life on Apr 16, 2016 3:49:31 GMT 5

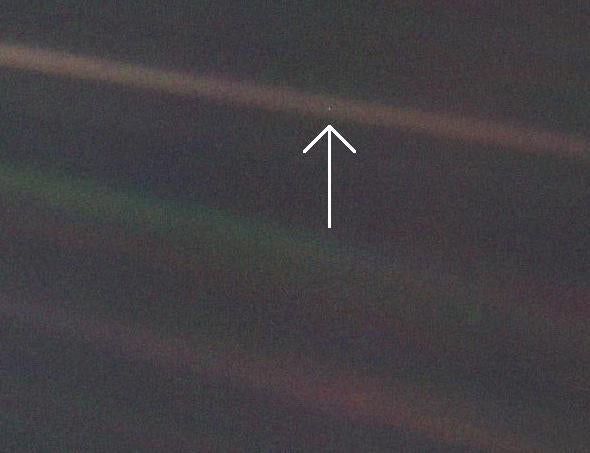

A paper came out recently that suggests biotic factors being largely responsible for extinction of Megalodon: onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jbi.12754/fullThe paper also reveals distribution pattern of Megalodon over period of time which is really informative. However, I have problem with the conclusions drawn from it. First; there is no way to tell how many sharks existed during Miocence and Pliocene in real life, based on fossil evidence alone. Second; impact of climatic conditions on the functioning of an organism does not gets captured in fossil record. Third; authors haven't provided information about fossils that legitimately came from northern hemisphere during Pliocene epoch where water temperature was really low. Fourth; the world began to change since Mid-Miocene as a apparent from following revelations: - Cooling trend since Mid-Miocene - Decline in biodiversity since Mid-Miocene - Geographical changes and their implications This image is self-explanatory:  Black dots indicate Megalodon fossil record during Pliocene epoch. So how-come so many experts have been wrong in assuming that environmental conditions restricted Megalodon's movements in the northern hemisphere or polar regions in general? A simple look at the migratory patterns of extant cetaceans will tell you that whales tend to migrate to polar regions to feed: www.whaleroute.com/migrate/Moreover, competition theory is so immature. What was stopping Megalodon from eating other predators such as other sharks (including great white sharks) and dolphins? I'd blame decline in biodiversity, environmental constraints and cannibalism for extinction of Megalodon. The adults would have been affected most due to shortage of food sources around the globe. Adaptation problems in short. Present situation is much better for marine animals then it was during glaciation period. Cetacean populations significantly declined during glaciation period and rebound after environmental conditions became more stable. The authors are too much tied-up in determining scientific methods to figure out Megalodon's extinction drivers. Pimiento is just thirsty for publications. |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Apr 16, 2016 4:11:25 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Apr 18, 2016 19:34:14 GMT 5

I also found Pimiento, et al's conclusions a bit premature. With the caveat that I need to read the article more carefully, after doing a cursory reading, it looked like the researchers did a presumably careful analysis Meg's population density during various epochs affected by climate change and argued that Meg populations did not seem vulnerable to decline in colder weather. But then, ergo, their conclusion was that if the extinction wasn't from climate changes, it must have been from competition, with the supporting correlation that the purported decline or Megalodon started around the same time as the rise of great white and orca ancestors.

Certainly, the idea of predator competition has been around a long time in discussing Megalodon's extinction. Perhaps it was a factor but I have a hard time believing it to be the predominant one. As far as great whites, it is almost certain that Megalodon and great whites occupied completely different prey strata at different trophic levels. Even accounting for great whites possibly reaching larger sizes in the Miocene and Pliocene, I am very doubtful that they were regularly attacking the medium to large whales Meg targeted. Likewise, I doubt they could scavenge dead whales at a rate that would drastically affect another food source for Meg, and of course Meg could easily displace great whites or probably any other animal at a carcass.

Similar concerns for orcas. What I believe we know is that early orca ancestors were markedly smaller than modern ones, maybe only reaching 4 or 5 meters. That would likely make them an occasional prey target for big sharks like great whites, not a global game changer devastating Megalodon populations. 7-8 meters orcas don't devastate current whale populations and often struggle with large whale prey. How could their much smaller ancestors have done so much damage to whale populations (which were admittedly of a smaller average size than today's whales) as to deprive Megalodon's food source?

One glaring hole in this article is its failure to address (unless I missed it in my first quick read) the fact that for many millions of years, Megalodon easily co-existed with more formidable sharks than great whites and much larger and dangerous cetaceans than prehistoric orcas, such as raptorial sperm whales of various types. So unless these small orcas existed in gigantic pods, which simply drove off/ate all of Meg's prey, I think the small orca ancester/great white competition theory is largely a dead end. It seems the researchers did meticulous research, (although they may have drawn the wrong conclusions) about the affect of climate change on Meg population, and then leaped to an alternative competition conclusion upon which they had conducted relatively little research.

Increased competition, particularly from orca packs, may have had an impact, but my guess is that it was a relatively small factor set against a much bigger backdrop of migrating prey retreating to arctic locations where Meg simply couldn't follow.

|

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Apr 18, 2016 22:02:44 GMT 5

My understanding is that megalodon was less and less adapted to the trophic webs than the newer more modest-sized/social apex predators. Hence he was outcompeted in an environment it wasn't anymore fitted for.

What I find interesting in the maps are the modern oceanic areas that are the most adapted for the species hypothetical survival.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Apr 18, 2016 23:32:29 GMT 5

As far as great whites, it is almost certain that Megalodon and great whites occupied completely different prey strata at different trophic levels. Even accounting for great whites possibly reaching larger sizes in the Miocene and Pliocene, I am very doubtful that they were regularly attacking the medium to large whales Meg targeted. Likewise, I doubt they could scavenge dead whales at a rate that would drastically affect another food source for Meg, and of course Meg could easily displace great whites or probably any other animal at a carcass. The mechanisms of interspecific competition are more complex than that. They aren’t simply based on which animal is more formidable in a one-on-one confrontation. The best example of this is the pleistocene megafauna, which almost universally disappeared in favour of smaller, less formidable, but more versatile analogues or relatives. The (only) way I’d see great whites compete with Carcharocles would be via competing with juveniles for pinnipeds and small cetaceans. But you are right, this doesn’t seem to consider that there were other lamniforms of roughly similar, or at least overlapping size to great whites (e.g. Alopias grandis/sp., Parotodus benedenii…) that it did coexist with for extended periods of time. Blaming C. carcharias alone is unrealistic. But in conjunction with a change in the available prey base, this is a different story. No doubt the only relevant competition when it came to anything bigger than a right-whale calf would be orcas. But orcinine evolution is too obscurely documented to draw conclusions as of now. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Apr 18, 2016 23:49:38 GMT 5

Have any of you discussed these concerns with any of the authors, considering at least some of you are in contact anyway?

|

|

|

|

Post by spartan on Apr 19, 2016 0:33:39 GMT 5

I'm not really well versed in this topic, but as far as I understood Megalodon's decline went along with reduced diversity in large cetaceans. Could it be that something "simply" severely reduced the food sources of mysticetes which lead to the extinction of several whale species and thus robbed Megalodon of its main prey source?

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Apr 19, 2016 0:36:52 GMT 5

The (only) way I’d see great whites compete with Carcharocles would be via competing with juveniles for pinnipeds and small cetaceans. But you are right, this doesn’t seem to consider that there were other lamniforms of roughly similar, or at least overlapping size to great whites (e.g. Alopias grandis/sp., Parotodus benedenii…) that it did coexist with for extended periods of time. Blaming C. carcharias alone is unrealistic. But in conjunction with a change in the available prey base, this is a different story. No doubt the only relevant competition when it came to anything bigger than a right-whale calf would be orcas. But orcinine evolution is too obscurely documented to draw conclusions as of now. I remember having some discussions about young Megalodons occurring in high concentrations (which explains why one compilation of median weights fluctuated between 10 to 20 t). As such, I do believe that the addition of extra predators comparable in size to young Megalodons would have mattered (but of course not exclusively). |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Apr 19, 2016 0:43:45 GMT 5

Meg was simply less versatile in the newer environments thus was outcompeted because no longer well adapted. The details need to be studied further though.

Is there another of apex predator species that lasted as long or longer? The oldest records appear to be 23 millions years old. That's an impressively long existence. Switek wrote few creature can claim such a long lifespan.

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Apr 19, 2016 2:24:50 GMT 5

As far as great whites, it is almost certain that Megalodon and great whites occupied completely different prey strata at different trophic levels. Even accounting for great whites possibly reaching larger sizes in the Miocene and Pliocene, I am very doubtful that they were regularly attacking the medium to large whales Meg targeted. Likewise, I doubt they could scavenge dead whales at a rate that would drastically affect another food source for Meg, and of course Meg could easily displace great whites or probably any other animal at a carcass. The mechanisms of interspecific competition are more complex than that. They aren’t simply based on which animal is more formidable in a one-on-one confrontation. The best example of this is the pleistocene megafauna, which almost universally disappeared in favour of smaller, less formidable, but more versatile analogues or relatives. The (only) way I’d see great whites compete with Carcharocles would be via competing with juveniles for pinnipeds and small cetaceans. But you are right, this doesn’t seem to consider that there were other lamniforms of roughly similar, or at least overlapping size to great whites (e.g. Alopias grandis/sp., Parotodus benedenii…) that it did coexist with for extended periods of time. Blaming C. carcharias alone is unrealistic. But in conjunction with a change in the available prey base, this is a different story. No doubt the only relevant competition when it came to anything bigger than a right-whale calf would be orcas. But orcinine evolution is too obscurely documented to draw conclusions as of now. I wasn't implying that this is a one on one confrontation. Merely that adult Megalodon, probably could compete with orcas and great whites quite readily, all things being equal. But of course as we know all things were not equal. You raise a good point about juveniles maybe having difficulty competing against great whites and orcas, but as mentioned juvenile Megs had been competing against similar competitors - shark and cetacean - for millions of years without detriment. However, I suppose that if prehistoric orcas functioned with intelligent pod behavior - even if if they were much smaller than contemporary orcas - they could be serious competitor or even a predator of juvenile Megs, and perhaps this was a level of cooperative competition/pod behavior that Megalodons had never faced before. I still tend to think a very large extinction factor would be larger whales learning/adapting to migrate to colder waters, where Megs either could not go or preferred not to go. If the adults were being hit by that factor and juveniles were being pressured by competitive factors, it could create the perfect scenario for extinction. So I tend to agree overall with the land megafauna analogy. In the end, Megalodon just could not adapt to multiple changes in its environment. That ultimately is the danger of megafauna in general, they tend to sacrifice a certain degree of flexibility and versatility, for size and strength. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Apr 19, 2016 4:27:57 GMT 5

And that’s what we can only really guess at, and what I tried to express; competitive success is not so straightforward. There are many reasons one species can outcompete another, and no doubt some potential factors can’t be, or at least aren’t yet determinable for C. megalodon.

Pimiento et al. imply there was such detriment, and propose these competitors as a mechanism to explain it:

Pimiento, Catalina, Bruce J. MacFadden, Christopher F. Clements, Sara Varela, Carlos Jaramillo, Jorge Velez-Juarbe, and Brian R. Silliman. 2016. Geographical distribution patterns of Carcharocles megalodon over time reveal clues about extinction mechanisms. Journal of Biogeography, doi:10.1111/jbi.12754.

I’m not exactly convinced that this is hard evidence, nor do I think the authors try to sell it as such. All this means is that there is no statistical evidence for direct effects of climate change being the extinction-mechanism, and an alternative has been proposed that better fits their data, not as the sole cause of extinction, but as the main contributing factor.

As they concluded: "Further studies of predator–prey interactions in relevant ancient marine ecosystems are needed to identify the causes of its extinction."

But if we assume that their methods for determining the species abundance are sound, then in principle this statement is too, and reflects exactly what you would expect based on your objection.

The question you already posed is whether the interpretation is sound, and we do not know. All we can say is that their data actually fit their alternative hypothesis (drop in abundance correlates with competition) and don’t fit the one they reject (drop in abundance and distribution should follow global temperature trends). It will be intriguing to see responses to this, and additional data. Major new factors could be discovered any time too. The more important part about this is realizing that the data aren’t consistent with meg being affected mainly by climate change.

What I find odd is that an extinction beginning in the late Miocene would have taken awfully long. Literally surviving the first generation of competitors that were alledgedly responsible based on the current state of knowledge, so a very slow process.

To evaluate the competitor hypothesis, the next step would be to put the qualitative arguments to the same quantitative test as they did with the climate-hypothesis, and see if this, in turn, really provides a more consistent explanation.

If the chronospecies-hypothesis is correct, then C. megalodon evolved directly from C. subauriculatus (so that’s one potential competitor down, but this remains to be confirmed). So someone would have to conduct a similar study, and see whether the abundance of other large macropredators that would be potential competitors for juvenile or adult megs increased since then.

It certainly seems that some interesting studies are being turned out at the moment. It’s truly a shame that scientific energy couldn’t be applied to resolving the huge number of issues that could potentially be resolved by rescuing and properly studying the peruvian skeletons.

If I’m not mistaken, one specimen of O. citoniensis is known (described in Italian and, I imagine, not readily available to a large portion of this world’s researchers), and that’s pretty much all we have on Orcinus’ pre-pleistocene evolution. So we can say very little about what Pliocene orcas could or could not have done. The only thing is that it appears they were either rare on a global scale, or restricted to pelagic environments, otherwise we’d have more fossils.

|

|

|

|

Post by Life on Apr 19, 2016 13:38:06 GMT 5

Somebody should ask the authors that where is the evidence of abundance of (large) macropredatory odontocetes during Pliocene epoch that supposedly competed with Megalodon for similar food sources? O. citoniensis is the only name that comes to mind and it reached only 4m in TL. Fossil records of this species do not imply global distribution so far. Moreover, this species also became extinct around 2.6 million years ago. History of odontocete diversity at a glance:  Source: Source: Whales, Whaling, and Ocean Ecosystems (James A. Estes) |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Apr 19, 2016 14:21:56 GMT 5

What about the teeth referred to Hoplocetus borgerhoutensis, H. obesus and Scaldicetus minor discussed by Hampe (2006)? Some fossil physeteroids with enamel-covered tooth crowns (similar to the macrophagous forms we know from the Miocene) seemingly survived into the Pleistocene: www.jstor.org/stable/25835890So all in all, I know 5 ocurrences of potentially macrophagous, extinct odontocetes dating from the Pliocene or younger. That sample is limited, but perhaps I’m not aware of all the collections. Similar methods to those employed in estimating C. megalodon abundance would be in order to analyse the prevalence of these fossils. ––Ref: Hampe, Oliver (2006): Middle/late Miocene hoplocetine sperm whale remains (Odontoceti: Physeteridae) of North Germany with an emended classification of the Hoplocetinae. Fossil Record 9 (1) pp. 61-86. |

|

|

|

Post by Life on Apr 19, 2016 14:48:28 GMT 5

theropodBut the problem is that some so-called experts are "assuming" them to be big-game hunters without providing concrete evidence.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Apr 19, 2016 15:14:41 GMT 5

The teeth resemble those of other big-game hunting stem-physeteroids and show signs of wear, in almost every description of a stem-physeteroid that had these features, an inferred orca-like ecology has been mentioned, so why would they not be big-game hunters?

|

|