Post by Infinity Blade on Aug 20, 2016 7:36:46 GMT 5

Amphicyon spp.

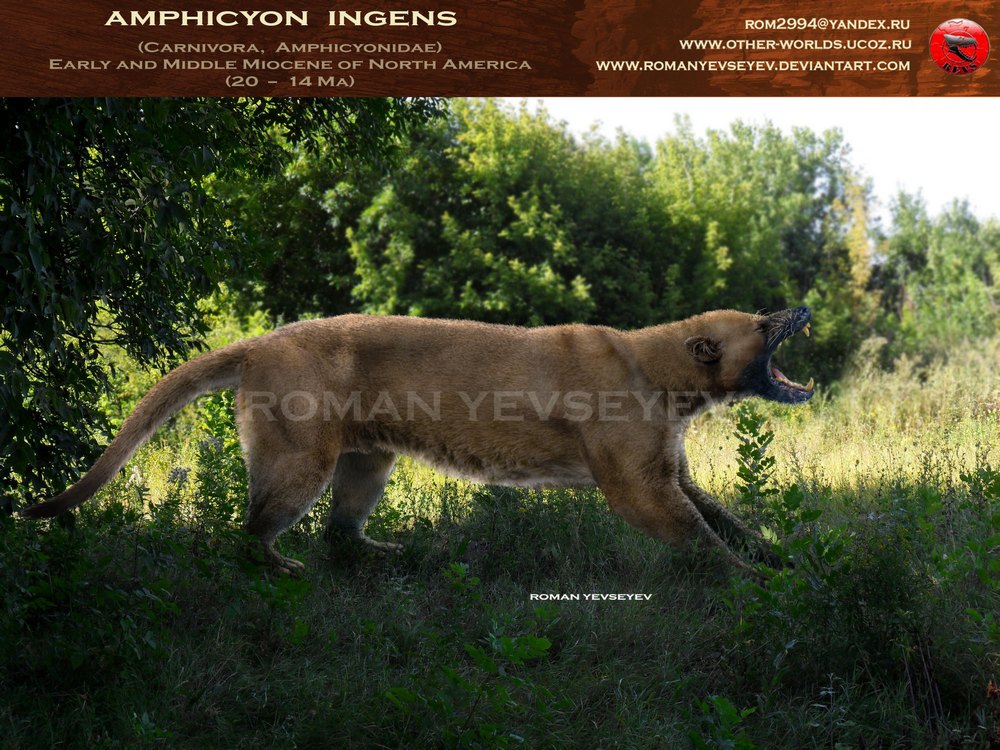

Reconstruction of A. ingens. © @ DeviantArt user RomanYevseyev

Temporal range: early Miocene to Pleistocene (Burdigalian-Gelasian; Late Hemingfordian-Blancan (NALMA); 17.5[1]-2.588Ma[2])

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Clade: Eutheriodonta

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicynodontia

Infraorder: Eucynodontia

Parvorder: Probainognathia

Superfamily: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

Clade: Holotheria

Superlegion: Trechnotheria

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Eutheria

Infraclass: Placentalia

Subcohort: Exafroplacentalia

Magnorder: Boreoeutheria

Superorder: Laurasiatheria

(unranked): Ferae

(unranked): Carnivoramorpha

Order: Carnivora

Suborder: Caniformia

Family: †Amphicyonidae

Genus: †Amphicyon

Species: †A. argentinus

†A. major

†A. ingens

†A. longiramus

†A. frendens

†A. galushai

†A. giganteus

†A. gracilis

†A. intermedius

†A. pontoni

†A. reinheimeri

†A. riggsi[2]

Amphicyon (“ambiguous dog”) is an extinct genus of caniform carnivoran of the family Amphicyonidae that lived in the United States of America (California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Maryland, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas), Austria, Portugal, Turkey, France, Germany, China, India, Namibia, Nepal, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia, Spain, and Ukraine[2] from 17.5[1] to 2.588 million years ago[2] (early Miocene to Pleistocene). Members of its family are also commonly referred to as bear dogs.

Description and ecomorphology:

Amphicyon ingens was the largest species of Amphicyon; the largest known individuals were 550 kilograms in weight, making it the largest carnivoran in North America from 17.5 to 14 million years ago (at which point it became extinct in North America).[1]

Sorkin (2006) analyzed the morphology of Amphicyon to determine what models of diet and hunting behavior are most likely for it. As he described the amphicyonids in his study, “...the dental and skeletal morphology of Amphicyon, Ischyrocyon and other members of the subfamily Amphicyoninae was unlike that of any living carnivoran. These bear-dogs possessed short distal limb segments, plantigrade hind feet, and broad molars of the living bears (Ursidae, Ursinae), long narrow rostrum and moderately sectorial carnassials of the living dogs (Canidae, Caninae), and flexible lumbar segment of the vertebral column and long tail of the living cats (Felidae) (Viranta 1996; Hunt 1998a; Ginsburg 1999)”.[1]

The relative grinding area (RGA) of the lower molars of Amphicyon fell within the range of those of primarily or obligatory carnivores (by contrast, the RGA of the omnivorous brown bear was three to four times higher than that of the studied amphicyonids). Moreover, the wear facets on the upper molars suggested that they had a sectorial function (i.e. shearing meat and/or bone). These both suggest that Amphicyon was at least a primary carnivore, if not an obligate one.[1]

The distal forelimb segments (i.e. the radius) of Amphicyon were as long relative to the proximal limb segments (i.e. the femur) as in the tiger (Panthera tigris). In the hindlimbs, the relative size of the distal segments (i.e. the tibia) was intermediate between the brown bear (Ursus arctos) and the tiger. This suggests that Amphicyon was well-equipped for ambush hunting; it most likely would have hidden itself in dense vegetation and briefly chased its prey (its chase would have been shorter than an African lion’s (Panthera leo)). However, the olecranon process in late Hemingfordian Amphicyon sp. was more caudally bent than that of a tiger (it was even more so A. ingens). Also, the olecranon was proportionately significantly shorter than in a big cat. This would reduce the tricep muscles’ leverage while crouching and in turn, how well it could accelerate from that position. Therefore, Amphicyon was not as adapted for ambush hunting as a big cat with distal limb segments proportionally as long.[1]

The lumbar vertebrae of Amphicyon possessed cranially angled spines and a substantial amount of space in between them, an important adaptation for fast movement (it increases effective stride length with extensive flexion and extension). The long spines suggest the presence of powerful extensor muscles. That said, the transverse processes were almost horizontal, not ventrally projecting as in say, a tiger; this would have allowed for limited leverage for the intertransversarial muscles to flex the vertebrae. This would have limited acceleration ability. This, in addition to the short tibiae and plantigrade pedes, would have made Amphicyon inferior to big cats in terms of the ability to rapidly accelerate and ambush prey.[1]

Once Amphicyon did catch up to its prey, it would have grappled it with its forelimbs; this is something it would have been very adept at. The scapula of Amphicyon had a large postscapular fossa, suggesting the presence of powerful subscapularis minor muscles that would have prevented the humeri from dislocating from the scapulae. The humeri also had deltopectoral crests. The deltopectoral crest was substantially longer relative to the whole humerus than the deltoid and pectoral ridges of typical cats. This would have resulted in more distal insertions and in turn, greater leverage of the deltoid and pectoral muscles. There was a well-developed medial epicondyle on the humerus (as in big cats), suggesting a powerful pronator teres muscle and wrist and digit flexors (which allow for forearm pronation and digit and wrist flexion as great as that of big cats). The shallower trochlea of the humeral condyle (compared to a tiger) and very mobile radioulnar joints allowed for forearm pronation-supination that was as great, if not greater, than in modern big cats. Despite a lack of retractable claws, grappling capacity would most certainly have been very substantial in Amphicyon.[1]

Amphicyon most likely killed in a different manner than modern big cats do. Like extant cursorial predators (e.g. spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) and grey wolf (Canis lupus)), Amphicyon had a narrow snout relative to the basal length of the skull. Small infraorbital foramina also suggest that it did not have the tactile specializations to deliver carefully directed bites to prey.[1]

Overall, it seems that Amphicyon would have ambushed its prey, but would have pursued its prey for a longer distance and slower speed than extant felids do. The short distal segments of the limbs suggest it did not chase after prey for a long distance. They (along with an at least primarily carnivorous diet) also suggest that Amphicyon did not largely survive on cursorial ungulates, which would have been more specialized for fast running than it was. However, its locomotory performance would have been on par with those of mediportal ungulates, and these animals (namely ticholeptine oreodonts and rhinoceri) were in ample quantity during the time of Amphicyon.[1]

Amphicyon's proportionately shorter distal limb segments (in comparison to the possibly social Daphoenodon superbus) might suggest it was a solitary hunter (in a similar manner to how pack-hunting lions have more elongated distal limb segments than solitary tigers).[1]

Amphicyon would have preyed upon animals similar (or even greater) in size to itself. One predator with a canid-esque snout and known to have killed similar sized prey was the thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus). One individual would have stood on top of a fallen prey item and tore open the ribcage; Amphicyon would likely have done the same. Tearing into the neck and severing important blood vessels could have been another way of dispatching prey.[1] Amphicyon evidently possessed a powerfully constructed skull with a large sagittal crest and fairly wide zygomatic arches (giving it a powerful bite) and long canines, allowing it to deliver a formidable killing bite.

Skull of A. ingens. Note the large sagittal crest, long canines, and zygomatic arches.

References:

[1] Sorkin, B. (2006). Ecomorphology of the giant bear-dogs Amphicyon and Ischyrocyon. Historical Biology, 2006; 18(4): 375–388.

[2] Fossilworks page

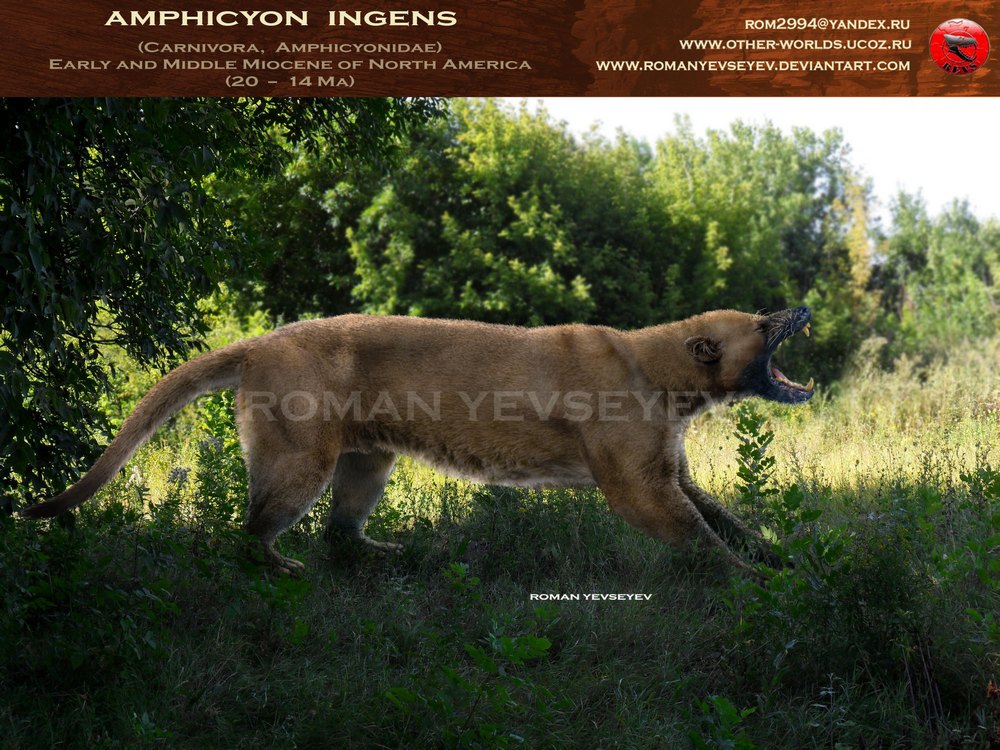

Reconstruction of A. ingens. © @ DeviantArt user RomanYevseyev

Temporal range: early Miocene to Pleistocene (Burdigalian-Gelasian; Late Hemingfordian-Blancan (NALMA); 17.5[1]-2.588Ma[2])

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Clade: Eutheriodonta

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicynodontia

Infraorder: Eucynodontia

Parvorder: Probainognathia

Superfamily: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

Clade: Holotheria

Superlegion: Trechnotheria

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Eutheria

Infraclass: Placentalia

Subcohort: Exafroplacentalia

Magnorder: Boreoeutheria

Superorder: Laurasiatheria

(unranked): Ferae

(unranked): Carnivoramorpha

Order: Carnivora

Suborder: Caniformia

Family: †Amphicyonidae

Genus: †Amphicyon

Species: †A. argentinus

†A. major

†A. ingens

†A. longiramus

†A. frendens

†A. galushai

†A. giganteus

†A. gracilis

†A. intermedius

†A. pontoni

†A. reinheimeri

†A. riggsi[2]

Amphicyon (“ambiguous dog”) is an extinct genus of caniform carnivoran of the family Amphicyonidae that lived in the United States of America (California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Maryland, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas), Austria, Portugal, Turkey, France, Germany, China, India, Namibia, Nepal, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia, Spain, and Ukraine[2] from 17.5[1] to 2.588 million years ago[2] (early Miocene to Pleistocene). Members of its family are also commonly referred to as bear dogs.

Description and ecomorphology:

Amphicyon ingens was the largest species of Amphicyon; the largest known individuals were 550 kilograms in weight, making it the largest carnivoran in North America from 17.5 to 14 million years ago (at which point it became extinct in North America).[1]

Sorkin (2006) analyzed the morphology of Amphicyon to determine what models of diet and hunting behavior are most likely for it. As he described the amphicyonids in his study, “...the dental and skeletal morphology of Amphicyon, Ischyrocyon and other members of the subfamily Amphicyoninae was unlike that of any living carnivoran. These bear-dogs possessed short distal limb segments, plantigrade hind feet, and broad molars of the living bears (Ursidae, Ursinae), long narrow rostrum and moderately sectorial carnassials of the living dogs (Canidae, Caninae), and flexible lumbar segment of the vertebral column and long tail of the living cats (Felidae) (Viranta 1996; Hunt 1998a; Ginsburg 1999)”.[1]

The relative grinding area (RGA) of the lower molars of Amphicyon fell within the range of those of primarily or obligatory carnivores (by contrast, the RGA of the omnivorous brown bear was three to four times higher than that of the studied amphicyonids). Moreover, the wear facets on the upper molars suggested that they had a sectorial function (i.e. shearing meat and/or bone). These both suggest that Amphicyon was at least a primary carnivore, if not an obligate one.[1]

The distal forelimb segments (i.e. the radius) of Amphicyon were as long relative to the proximal limb segments (i.e. the femur) as in the tiger (Panthera tigris). In the hindlimbs, the relative size of the distal segments (i.e. the tibia) was intermediate between the brown bear (Ursus arctos) and the tiger. This suggests that Amphicyon was well-equipped for ambush hunting; it most likely would have hidden itself in dense vegetation and briefly chased its prey (its chase would have been shorter than an African lion’s (Panthera leo)). However, the olecranon process in late Hemingfordian Amphicyon sp. was more caudally bent than that of a tiger (it was even more so A. ingens). Also, the olecranon was proportionately significantly shorter than in a big cat. This would reduce the tricep muscles’ leverage while crouching and in turn, how well it could accelerate from that position. Therefore, Amphicyon was not as adapted for ambush hunting as a big cat with distal limb segments proportionally as long.[1]

The lumbar vertebrae of Amphicyon possessed cranially angled spines and a substantial amount of space in between them, an important adaptation for fast movement (it increases effective stride length with extensive flexion and extension). The long spines suggest the presence of powerful extensor muscles. That said, the transverse processes were almost horizontal, not ventrally projecting as in say, a tiger; this would have allowed for limited leverage for the intertransversarial muscles to flex the vertebrae. This would have limited acceleration ability. This, in addition to the short tibiae and plantigrade pedes, would have made Amphicyon inferior to big cats in terms of the ability to rapidly accelerate and ambush prey.[1]

Once Amphicyon did catch up to its prey, it would have grappled it with its forelimbs; this is something it would have been very adept at. The scapula of Amphicyon had a large postscapular fossa, suggesting the presence of powerful subscapularis minor muscles that would have prevented the humeri from dislocating from the scapulae. The humeri also had deltopectoral crests. The deltopectoral crest was substantially longer relative to the whole humerus than the deltoid and pectoral ridges of typical cats. This would have resulted in more distal insertions and in turn, greater leverage of the deltoid and pectoral muscles. There was a well-developed medial epicondyle on the humerus (as in big cats), suggesting a powerful pronator teres muscle and wrist and digit flexors (which allow for forearm pronation and digit and wrist flexion as great as that of big cats). The shallower trochlea of the humeral condyle (compared to a tiger) and very mobile radioulnar joints allowed for forearm pronation-supination that was as great, if not greater, than in modern big cats. Despite a lack of retractable claws, grappling capacity would most certainly have been very substantial in Amphicyon.[1]

Amphicyon most likely killed in a different manner than modern big cats do. Like extant cursorial predators (e.g. spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) and grey wolf (Canis lupus)), Amphicyon had a narrow snout relative to the basal length of the skull. Small infraorbital foramina also suggest that it did not have the tactile specializations to deliver carefully directed bites to prey.[1]

Overall, it seems that Amphicyon would have ambushed its prey, but would have pursued its prey for a longer distance and slower speed than extant felids do. The short distal segments of the limbs suggest it did not chase after prey for a long distance. They (along with an at least primarily carnivorous diet) also suggest that Amphicyon did not largely survive on cursorial ungulates, which would have been more specialized for fast running than it was. However, its locomotory performance would have been on par with those of mediportal ungulates, and these animals (namely ticholeptine oreodonts and rhinoceri) were in ample quantity during the time of Amphicyon.[1]

Amphicyon's proportionately shorter distal limb segments (in comparison to the possibly social Daphoenodon superbus) might suggest it was a solitary hunter (in a similar manner to how pack-hunting lions have more elongated distal limb segments than solitary tigers).[1]

Amphicyon would have preyed upon animals similar (or even greater) in size to itself. One predator with a canid-esque snout and known to have killed similar sized prey was the thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus). One individual would have stood on top of a fallen prey item and tore open the ribcage; Amphicyon would likely have done the same. Tearing into the neck and severing important blood vessels could have been another way of dispatching prey.[1] Amphicyon evidently possessed a powerfully constructed skull with a large sagittal crest and fairly wide zygomatic arches (giving it a powerful bite) and long canines, allowing it to deliver a formidable killing bite.

Skull of A. ingens. Note the large sagittal crest, long canines, and zygomatic arches.

References:

[1] Sorkin, B. (2006). Ecomorphology of the giant bear-dogs Amphicyon and Ischyrocyon. Historical Biology, 2006; 18(4): 375–388.

[2] Fossilworks page