|

|

Post by Life on Jan 26, 2017 22:30:31 GMT 5

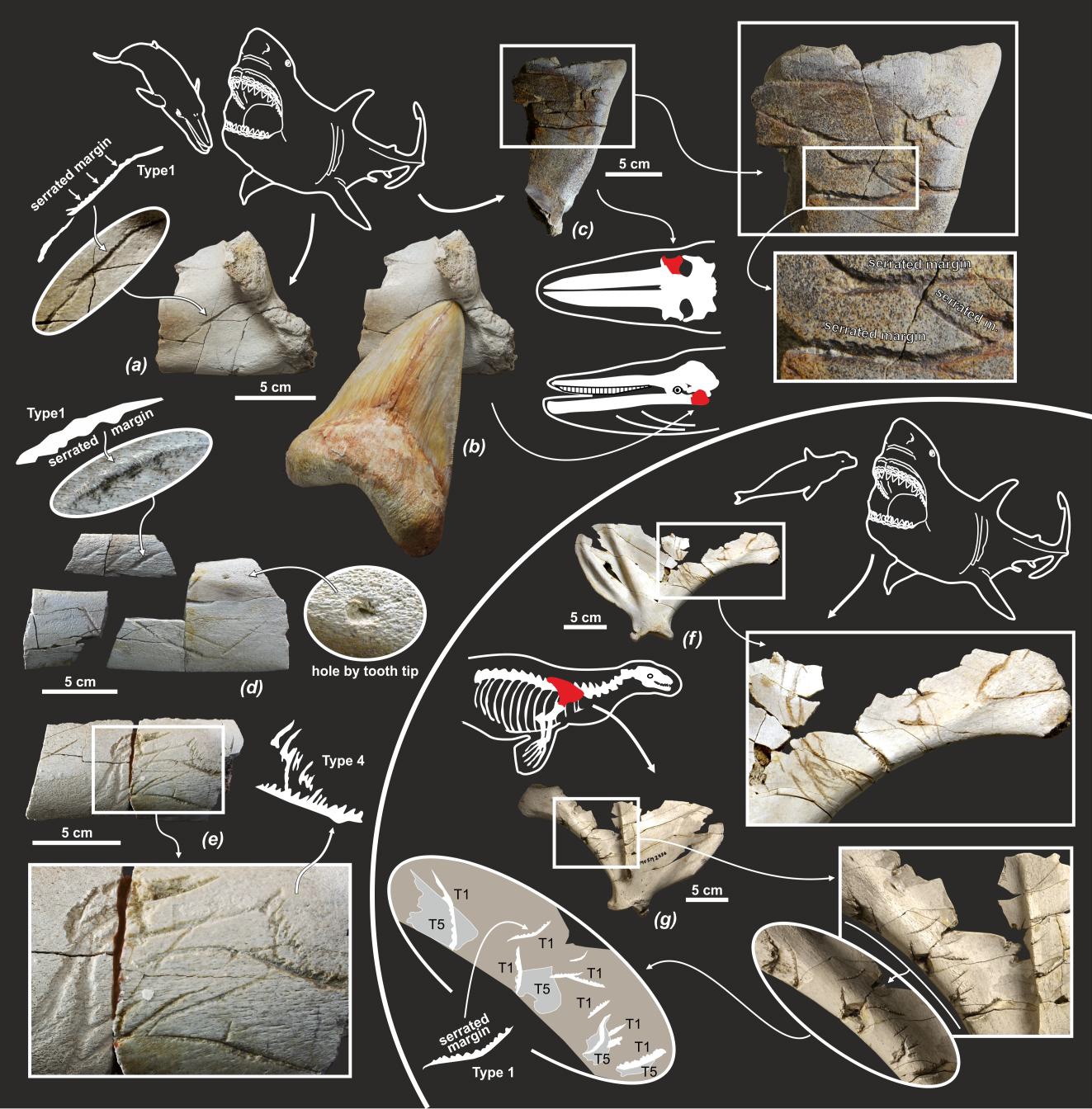

We report on bite marks incising fossil mammal bones collected from upper Miocene deposits of the Pisco Formation exposed at Aguada de Lomas (southern Peru) and attributed to the giant megatooth shark Carcharocles megalodon. The bitten material includes skull remains referred to small-sized baleen whales as well as fragmentary cetacean and pinniped postcrania. These occurrences, the first in their kind from the Southern Hemisphere, significantly expand the still scarce record of bite marks for C. megalodon; moreover, for the first time a prey (or scavenging item) of C. megalodon is identified at the species level (as Piscobalaena nana, a diminutive member of the extinct mysticete family Cetotheriidae). Due to the fragmentary nature of the studied material, the exact origin of the detected marks (i.e., by scavenging or by active predation) cannot be ascertained. Nevertheless, relying on actualistic observations and size-based considerations, we propose that diminutive mysticetes (e.g., cetotheriids) were some of the target prey of adult C. megalodon, at least along the coast of present-day Peru. C. megalodon is thus here interpreted as an apex predator whose trophic spectrum was focused on relatively small-sized prey. Lastly, we propose a link between the recent collapse of various lineages of diminutive mysticetes (observed around 3 Ma) and the extinction of C. megalodon (occurring around the end of the Pliocene). Source: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031018216305417 |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Jan 28, 2017 19:05:06 GMT 5

There are a few caveats in this theory, Dana Ehret quoted one of them. But Dana Ehret, curator of palaeontology at the Alabama Museum of Natural History, believes megalodon may also have targeted larger whales from time to time.

“I’ve seen a specimen from Virginia yet to be published of a fairly large baleen whale found with a megalodon tooth lying on top of an indentation in the bone,” he says.

But he adds it is unclear if the whale was alive or dead when the shark pounced. “It could have been scavenging on the whales like modern white sharks do today,” Ehret says.

Some modern sharks, however, have been seen actively targeting giant whales like humpbacks.

Catalina Pimiento Hernandez, a palaeontologist at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, says megalodon dietary preferences may have changed during their lifetime and depended on the area they inhabited. “More work is needed to be sure that megalodon globally preferred small prey rather than big,” she says.www.newscientist.com/article/2117802-largest-ever-shark-was-doomed-by-its-taste-for-dwarf-whales/The case of Kallal et al. 2012 is counter-intuitive as well and adult GWS do target right whales calves which are basically as massive as an adult GWS and are usually protected by their parents. Of course megalodon targeted primarily smaller whales simply because they were far more abundants. I've referred to these points to Lambert but got no response yet. |

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Feb 2, 2017 0:34:10 GMT 5

So I've been wanting to write about this for several weeks, ever since a new study came out. In summary, there's a study out in January from researchers in Italy, Belgium and Peru. The study is notable because it identifies, perhaps for the first time, actual species with associated Meg bite marks. The two species are from Peru, I believe, during the Miocene. They are a 5 meter prehistoric whale and a 5 meter extinct pinniped. I believe there may also be some adult size Meg teeth associated with at least some of the fossil remains. Nothing huge, something like 4-5 inch teeth. It's certainly interesting and noteworthy to be able to first report actual species that Meg fed upon in these two instances. But the researchers go far beyond that. From a sample size of two - they then go on to make an astonishing hypothesis that the evidence suggests that the gigantic shark preferred very small prey and thus went extinct largely when this small prey source went extinct. Numerous periodicals then picked up on this study and started reporting it as gospel. Some of the reports came with caveats - such as Dana Ehret, researcher from University of Florida, noting he had seen a Meg tooth and bite marks (unpublished) on a very large baleen whale vertebrate although he stated he could not, of course, know if the Meg killed or scavenged the whale. These types of studies concern me because it seems like the researchers may be wanting to make sensational conclusions based on truly enormous extrapolations rather than simply report on and study the existing data. We know for a fact that there were likely billions, even tens of billions, of Megalodon predatory/scavenging feeding events throughout the species' many millions of years of existence. These researchers take 2 - let me repeat - 2 of these instances to extrapolate an enormously speculative and unknowable "conclusion" that Meg was a small species predator. I suppose 300,000 years from now researchers may come across evidence of an African lion bite marks on a gazelle and similarly conclude that lions were small game specialists. This laughable assertion is based on the same type of logic these researchers are employing. Now that's not to say they aren't right. It's possible, that Meg preferred small prey, particularly since such relatively small prey was relatively abundant during much of its existence. But consider the very evidence we've seen elsewhere. There's multiple cases of Megalodon bite marks on 30 foot, 40 foot and even significantly larger cetacean fossils. There's probable Meg bite marks on large rorqual whales and large bowhead whales. In my "shark bites on fossil whales" thread, there's multiple examples of deep and damaging bites on very large whale vertebral centra. That thread alone casts some serious doubt on these researchers speculative conclusions. BTW, I'd be just as dubious if the researchers found bite marks on a very large whale and concluded on one or two cases that Meg was almost certainly a big prey seeker. It's simply way too small a database to make such a sweeping hypothesis. Even taking all the fossils we have on records with Meg bites - which would cover the gambit from very large to very small - would not lead any definitive conclusions. I worry when every new Meg study yet seems to strain to provide some heretofore unknown "discovery" about the predator. That's not really the best science, which usually proceeds cautiously, tentatively, and incrementally. Obviously, there are breakthroughs in any field of science, but they are usually supported by many smaller advances, and almost always carry far more underlying factual support than pinpointing two out of billions of predatory interactions. Here's a link to one of the best articles citing the study. The full study can be purchased for about $38, which I'm not willing to do. But if anyone wants to buy it and report on the full details, I'd be happy to hear it. Read more at: phys.org/news/2017-01-giant-ancient-shark-extinct-due.html#jCp(Phys.org)—A team of researchers with members from Italy, Belgium and Peru has found evidence that suggests the reason the giant shark megalodon went extinct millions of years ago, was because its small prey went extinct due to climate change. In their paper published in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, the team describes fossils they found in Peru and their link to the giant ancient shark. Megalodon lived approximately 17 to 2.6 million years ago, and at least some of the giant sharks grew to over 50 feet long, with jaws 10 feet wide. But why the largest shark to ever swim the world's oceans suddenly went extinct remains a mystery. In this new effort, the researchers report that they have found evidence that the reason might have been that the sharks had a penchant for eating tiny whales, which themselves went extinct due to climate change. The new evidence came in the form of 7-million-year-old mammalian fossils recently uncovered in southern Peru—they were of a species of dwarf baleen whale and an early relative of a modern seal (both of which grew to only 5 meters long)—both had bite marks that the researchers believe came from a megalodon—the first discovered evidence of a megalodon attack. This, the researchers suggest, indicates that one of megalodons' preferred meal choices was a type of small whale that went extinct, leaving the giant sharks with too little to eat. Prior research has suggested that the tiny baleen whales went extinct because they were unable to migrate to far-away feeding grounds as the Earth cooled, causing ice build-up at the poles, lower sea levels, and resulting in colder water. Large baleen whales, the ancestors of those alive today, were big enough to migrate for food, but those that were too small to make the trip died out. As the small whales disappeared, the researchers contend, the giant sharks found themselves without a reasonable substitute and unable to migrate themselves; because of that, they died out also. This newest evidence might just be part of the story, however, as other recent research has suggested that megalodons suffered from competition with white sharks and perhaps killer whales. Explore further: Prey scarcity and competition led to extinction of ancient monster shark More information: Alberto Collareta et al, Did the giant extinct shark Carcharocles megalodon target small prey? Bite marks on marine mammal remains from the late Miocene of Peru, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology (2017). DOI: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.01.001 Abstract We report on bite marks incising fossil mammal bones collected from upper Miocene deposits of the Pisco Formation exposed at Aguada de Lomas (southern Peru) and attributed to the giant megatooth shark Carcharocles megalodon. The bitten material includes skull remains referred to small-sized baleen whales as well as fragmentary cetacean and pinniped postcrania. These occurrences, the first in their kind from the Southern Hemisphere, significantly expand the still scarce record of bite marks for C. megalodon; moreover, for the first time a prey (or scavenging item) of C. megalodon is identified at the species level (as Piscobalaena nana, a diminutive member of the extinct mysticete family Cetotheriidae). Due to the fragmentary nature of the studied material, the exact origin of the detected marks (i.e., by scavenging or by active predation) cannot be ascertained. Nevertheless, relying on actualistic observations and size-based considerations, we propose that diminutive mysticetes (e.g., cetotheriids) were some of the target prey of adult C. megalodon, at least along the coast of present-day Peru. C. megalodon is thus here interpreted as an apex predator whose trophic spectrum was focused on relatively small-sized prey. Lastly, we propose a link between the recent collapse of various lineages of diminutive mysticetes (observed around 3 Ma) and the extinction of C. megalodon (occurring around the end of the Pliocene). |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 2, 2017 1:10:52 GMT 5

Life created a thread about this study earlier. Nevertheless, I agree with your main point.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 2, 2017 1:26:39 GMT 5

Thanks for pointing that out, I did not notice this.

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Feb 2, 2017 1:55:16 GMT 5

Yes, I missed the earlier post by Life as well. Grey, thanks for pointing out some responses to the study.

BTW, how goes your own Meg research paper? Any idea how it's progressing?

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Feb 10, 2017 1:17:37 GMT 5

Here's photographic evidence of Meglodon, "the small prey/picky eater" feeding on very large whales. Of course, we don't know if this was scavenging or predation but how could the authors of the above study draw such a speculative claim that Megalodon was primarily a small game predator when this evidence could plausibly suggest something quite different? I'm not saying Megalodon wasn't further challenged with larger, more formidable, faster and perhaps more cold tolerant whales, but to suggest they were really incapable or unwilling to tackle large prey - based on a paltry two example sample - does a real disservice to the fossil record. See Purdy's discussion on pages 67-76 below, in which he documents East Coast (Yorktown, Aurora, NC) occurrences of large adult teeth associated in fossil beds with large sperm whales, and mysticetes, and juvenile Meg teeth found in fossil beds associated with small whales, which he believes strongly correlates with their predatory preferences. He also documents that large whale caudal bones and flippers are found with Meg bite marks and shows a very large baleen whale bitten fossil, which may very well indicate a well known strategy for preying on larger whales. But to my knowledge (not having read the full article) the current authors of this study ignore such evidence (of course their study is also in Peru, a completely different geography). Still South American Megs appears to be among the largest in the fossil record, so I'm not sure why they wouldn't be equally able to adapt to larger prey. books.google.com/books?id=2My8M5tL-KIC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false - see page 76 for large baleen whale Meg bitten vertebrate from Pliocene.   Here's how paleodirect describes these huge bitten whale vertebrae, which btw were found in west coast of South America, where the authors to this study claim Meg was probably targeting mostly small prey. MEGALODON SHARK BITTEN SET OF THREE LARGE MIOCENE FOSSIL WHALE VERTEBRAE ARTICULATED IN ORIGINAL MATRIX

West Coastal South America

MIOCENE to PLIOCENE PERIOD: 23.3 - 1.81 million years ago

For those of you who have been watching our listings for some time, you may recognize this piece. We prepared the specimen about a year ago and had it on display in a portion of our gallery that was undergoing renovations. In the course of the construction work, it became excessively dusty so we brought it back to our lab and initially, just intended to lightly clean it. In the course of doing so, we discovered that a considerable layer of sediment and mineral concretion still coated the fossil bone and it necessitated a much better preparation effort than we initially gave it. Much to our pleasure and amazement, we realized, as the layers of rock were being blasted away that the vertebra that had formerly visible cross-bites, the bites were much deeper than originally seen and were more numerous than initially known. The real celebration though, came when we uncovered more of the mineral layer off of the vertebra laying next to the bitten one and saw that it had longitudinal bite marks more severe than the one next to it. THESE newly uncovered bite marks were THE MOST SEVERE of any fossil shark bitten vertebrae we have ever seen. The depth and length and width of the gashes in the bites could ONLY have been made by a very large MEGALODON shark!

We completed the preparation work and this time, were more thorough in removing the formerly hard-to-see mineral layer that covered the bone surface. The color beneath the rock that is in the bone is really beautiful and turned a very rare and interesting fossil into one that is even more beautiful in natural color. Out of all the Megalodon bitten fossils we have seen, this is the ONLY specimen that shows multiple bones of the same killed prey with incredibly deep and dramatic bite wounds in the bone.

As we photographed this specimen, shot after shot in the studio brought back that eerie memory of the intense scene in the film "Silence of the Lambs' where agent Starling, played by Jodie Foster, is attending her first real-life autopsy, examining her first 'Buffalo Bill" victim in the morgue. As the photographer blazes away with flash after flash, she is rattling off rote descriptions of wound after wound for the record with a seemingly emotionless air yet, beneath it, it is obvious she has a conflict with the unfolding horror she is witnessing - the horrible, life-less evidence of the attack on Bill's victim. The analysis of this specimen is one that offers a similar, eerie forensic story.

As you look closely at the nature of these bite marks, you can make some interesting theories based on the evidence of the bites. The one vertebra with the long bite gashes shows an initial impact bite in the center where the shark struck. Whether this was inflicted when the whale was still alive or already dead is impossible to say. Since sharks bite their prey, hold down, and then shake to saw off flesh, the bite gashes running along the axis of the centrum shows that the Megalodon struck from the side then bit and shook, hardest at first, and then to a lighter and lighter degree of repeat, successive bites, leaving multiple gashes running alongside each other and showing where the jaws opened and closed before and after each bite. This newly revealed vertebra that we have not seen in the first lab procedures shows far more dramatic bite wounds than anticipated. The additional re-cleaning of the other vertebra that we DID see first also revealed much deeper and more numerous bite wounds from the Megalodon but that vertebra has the bites running at a 90 degree perspective to the vertebra axis unlike the other. This second vertebra with opposing axis bite wounds tells us that the whale carcass was already dead and dismembered to where the shark was eating portions of the torso in sections at their ends.

Megalodon shark bitten fossils seldom offer this kind of insight and this is THE FIRST time we have witnessed a specimen like this for sale where you see a portion of multiple associate bitten and attacked whale vertebrae of the SAME whale. Numerous Megalodon fossils are known to have come from the same area as this whale fossil.

With a ban on the digging and export of fossils from South America, specimens like this are rare if ever seen on the public market. This spectacular partial skeleton fossil in concretion comes to us from a very old European collection. It is the only specimen of its kind we have to offer. We prepared this specimen and exposed the partial fossilized vertebral column of this giant whale that once lived millions of years ago with the fearsome Megalodon shark. All three vertebrae are still positioned as they were found - two are still in line as they would have been when the animal was alive and a third is to the side as found. This piece is very large and fully three dimensional with all vertebrae still connected with the original host rock. The depth and width of these bites can be none other than the work of the giant Megalodon shark. Megalodon shark fossils and fossils of its relatives can also be found in this same formation and region. A specimen such as this is perfect to display alongside a Megalodon shark tooth collection as this creature would have shared the same waters and served as the main food source for the largest and most dangerous shark that ever lived, the MEGALODON shark.

These vertebrae come from the lower region of the whale's spinal column. None of the vertebrae have been removed and replaced in the matrix - these are still in the position as they were found. We simply removed the matrix from around each vertebra. The heavy orange deposits are iron mineral stuck on to the vertebrae. One in particular appears to have been partially eaten on the surface and this iron mineral filled the region. We left this on as it was found. There is NO REPAIR AND NO RESTORATION OR COMPOSITING OF FOSSILS to this piece. This is truly an impressive, large articulated whale skeleton fossil from the days of the Earth's largest and most dangerous sharks. The Megalodon bites are severe and from a very large Megalodon shark millions of years ago.

It should be noted that paleodirect.com, which sold this huge vertebrate said it highly likely to be a very large sperm whale because "its size and proximity to associated Sperm whale teeth and Megalodon shark teeth" Here's the web link to these images as well as the three vertebrae shown above. web.archive.org/web/20121026080955/http://www.paleodirect.com/pgset2/mv21-024.htmFinally, here's a whale fossil vertebral centra, found in close association with a Megalodon tooth in a Florida phosphate mine.   |

|

|

|

Post by Life on Feb 16, 2017 13:03:58 GMT 5

I believe that a worldwide effort is needed to identify (and study) each case of trophic interaction involving a Megalodon and cooperation of private fossil collectors would be necessary in this regard! But who will take the initiative? I don't think many would be willing due to a number of reasons.

You can see that no significant effort has been made to study Megalodon specimens found in Peru! Lot of talk but no action.

It is also important to determine the ground realities of Pliocene marine ecosystem. What kind of species were part of this ecosystem? What geographical and climatic changes occurred during this period and how they affected marine mammals and sharks?

Extensive research is needed to determine the full picture of developments in Pliocene epoch to understand what went wrong for Megalodon.

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Feb 18, 2017 19:55:20 GMT 5

I believe that a worldwide effort is needed to identify (and study) each case of trophic interaction involving a Megalodon and cooperation of private fossil collectors would be necessary in this regard! But who will take the initiative? I don't think many would be willing due to a number of reasons. You can see that no significant effort has been made to study Megalodon specimens found in Peru! Lot of talk but no action. It is also important to determine the ground realities of Pliocene marine ecosystem. What kind of species were part of this ecosystem? What geographical and climatic changes occurred during this period and how they affected marine mammals and sharks? Extensive research is needed to determine the full picture of developments in Pliocene epoch to understand what went wrong for Megalodon. Yes, I agree that fossil collectors should open their Meg specimens (whether it be huge teeth, vertebral centra, or Meg bitten bones) for further study. Otherwise, we get arguably misleading studies like the one above. As to the Peru desert skeleton(s), you're absolutely right. From the pictures and reported measurements, it's quite suggestive that Honninger discovered something looking like a very big/complete Megalodon, but because of legalities in Peru and other reasons, nothing's been done. I've put him in touch with national media (who were incredibly eager to report on it), scientists like C. Ciampaglio who would have assisted him, and I offered him my own legal services. All to no avail, thus far. I think you are right about studying the Pliocene much more closely. Lately, the trend is to say the environmental changes did not cause/significantly contribute to Megalodon's extinction. That might be correct as to changes in water temperature (since Pimiento's study didn't show decreases in population density during colder periods). However, what about the closing of the Isthmus of Panama in the late Miocene? That could have greatly affected and limited cetacean travel patterns and hurt/affected both South American/Pacific and East Coast/Atlantic Megs, with global and dire repercussions for Megalodon and countless other species over the course of the Pliocene. Likely, it was combination of environmental changes, prey adaptability/evolution, competition, and prey disappearance. But to suggest Meg simply preferred not to or was incapable of predating on large cetaceans isn't really supported by the fossil record and what we know about Megalodon's size and biology. |

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Feb 19, 2017 22:30:47 GMT 5

From the January 2017 publication from Collareta, et al, documenting Megalodon feeding on a 5 meter cetacean and 5 meter pinniped. This is the study we've been discussing in this thread. Very good evidence of Meg feeding, and beautiful color imagery and grouping. However as I've stated, I don't believe it supports the conclusions drawn by the researchers, based on such a sparse sampling and their apparent ignoring of many fossil marks of Megalodon feeding on much larger cetaceans. www.thefossilforum.com/index.php?/topic/71269-dugong-rib-predation-marks/ |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Feb 21, 2017 4:20:13 GMT 5

Kallal et al. 2010 is at partially disagreeing with Bianucci et al. 2017.

This is a clear case of failed predation attempt from a possibly young megalodon on a rather large balaenopterid.

Something needs to be clarified, did megalodon encountered the first lineages of giant modern baleen whales species or have the gigantic species evolved AFTER megalodon's extinction ?

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Feb 21, 2017 20:25:38 GMT 5

Kallal et al. 2010 is at partially disagreeing with Bianucci et al. 2017. This is a clear case of failed predation attempt from a possibly young megalodon on a rather large balaenopterid. Something needs to be clarified, did megalodon encountered the first lineages of giant modern baleen whales species or have the gigantic species evolved AFTER megalodon's extinction ? Grey, I agree that the Kallal et al.'s study also suggests the possibility of Megalodon attacking much larger whales, although as you acknowledge we can't be sure it was a Megalodon or some other type of large shark. Along with the evidence of Megalodon bite marks on large whales, this type of study makes me even more skeptical of the claim that Megalodon only preferred to hunt quite small prey items. Why would a shark need to grow a maximum of 60 feet (fairly widely accepted) or even larger to hunt primarily small prey items? From an evolutionary standpoint, it makes little sense. However, if Megalodon faced larger prey/dangerous competitors/large rival apex predators, it would make much more sense to obtain gigantic sizes. The idea that large whales only evolved after Meg's extinction I think is incorrect to at least some extent. There are too many Meg bite marks on sizeable cetacean fossils. However, Meg may have only co-existed with larger cetaceans for a "short" period of time, maybe 1 million years or less. Perhaps the size of the whales alone had something to do with Meg's extinction, but it's just as likely that the whales larger body sizes gave them the tolerance (unlike their much smaller counterparts) to migrate to colder and polar regions for long periods of time, thus depriving Megalodon of a dependable food source. From the baleen whales perspective, larger body size had the evolutionary advantage of making them harder for Megalodon and other larger sharks or cetaceans (i.e. Livyatan and/or other pack hunters) to prey on them. PLUS larger body size would allow them to more easily tolerate colder, polar waters which gave them a double advantage of having access to a huge and probablyuntapped food source (huge amount of plankton) and would allow them to avoid contact with Megalodon and other large sharks for long periods of time during the year. I don't think Pimiento, et al's study forecloses this possibility at all. All their study tries to suggest is that Meg's population (on a very broad macro-level) didn't significantly fluctuate in the Miocene and Pliocene during colder ocean temperatures. But we could say the same thing about great whites, which obviously have survived long past Meg. Yet, even though great whites and other lamnids are "warm-blooded" after a fashion, they don't pursue prey into the polar regions. Great whites can be content with pinnipeds, fish, and smaller cetaceans/delphnids as their usual food source and can follow such food year around. However, if Megalodon actively pursued large whales as a primary source of food and such whales evolved to go to polar regions for large portions of the year where Meg could not/would not follow, the effect could be devastating on the large shark. In fact, perhaps Meg was forced to eat smaller prey more often in the Pliocene, because larger prey was so often out of reach. Also the effect of the closure of the Isthmus of Panama needs to be examined in much more detail, it had the potential for major disruptions of all food chains, and may have contributed to many cetaceans and other species' demise, including Megalodon. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Feb 22, 2017 4:07:43 GMT 5

This is a reasoning I myself don’t agree with, but some people draw an overly sharp line between "flesh grazing" and other forms of predation. That could be a reason why someone might ignore Kallal et al.’s specimen in this context.

As for the other examples, I agree that the properly studied material is just plain insufficient. Obviously it’s nothing new that taking into account unverifiable specimens only documented on private or commercial websites presents a problem in palaeontology.

|

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Feb 22, 2017 11:53:49 GMT 5

I'm not aware of any account of a white shark or any large shark flesh grazing a larger fish or cetacean (except for the specialized parasitic cookie-cutter). The authors I've read about dont seem to consider this as a form of predation. Kallal 2010 considers the case as a failed predation attempt. Flesh grazers dont fail anything, their purpose being to collect some food.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Feb 22, 2017 17:28:32 GMT 5

www.youtube.com/watch?v=l4xZC5xuRJAThere’s a big difference between a specialized parasite like the cookie-cutter and something like a false killer whale or tiger shark (or similar-sized young megalodon for that matter). One represents some level of threat to the prey (although the real threat those animals would, on their own, pose to a healthy adult rorqual is very debatable at best), at least being able to seriously injure and potentially kill it with its attack, the other none whatsoever. That’s a way more important distinction than the one between a tiger shark that swims in to take a few bites out of a baleen whale and a tiger shark that swims in attempting to kill a baleen whale, takes a few bites and realizes it’s too big to kill and that it can eat it without killing it. So there’s really no such thing as "flesh-grazers" in general. "Flesh-grazing" in a big predator is basically not distinguishable from a "failed predation attempt", only that it’s not so much failed completely as failed with regard to the purported objective of killing the prey item, which may or may not have actually been what the predator attempted. Of course the problem arises because in the fossil record, the only predation attempts that can usually be reliably determined not to be scavenging traces are failed predation attempts. There’s a tendency for some people to default to scavenging as an explanation for unhealed bite marks, so it’s not really surprising there might also be a tendency to As I said, I don’t think the difference is really relevant. If a 6m shark bites a large rorqual, that counts as a predatory attack for me. We can’t read the shark’s mind to determine whether it actually wanted to kill the whale or was willing to content itself with a mouthful of flesh and blubber to begin with. But as we’ve discussed before, some people draw a line there. So if as you say they don’t consider that form of predatory interaction to be true predation, that might be why they are at odds with what this specimen suggests if one does count it as predation.

|

|