Post by dinosauria101 on Apr 25, 2019 7:24:30 GMT 5

Megalosaurus bucklandii

Life reconstruction of Megalosaurus feeding on a carcass. © @ Mark Witton->.

Temporal range: Middle Jurassic; Bathonian age (166 Ma)

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Class: Reptilia or Clade: Sauropsida

Clade: Eureptilia

Clade: Romeriida

Clade: Diapsida

Clade: Neodiapsida

Clade: Archelosauria

Clade: Archosauromorpha

Clade: Archosauriformes

Clade: Crurotarsi

Clade: Archosauria

Clade: Avemetatarsalia

Clade: Ornithodira

Clade: Dinosauromorpha

Clade: Dinosauriformes

Clade: Dinosauria

Order: Saurischia

Clade: Eusaurischia

Suborder: Theropoda

Clade: Neotheropoda

Clade: Averostra

Clade: Tetanurae

Clade: Orionides

Clade: Avetheropoda

Clade: †Carnosauria(?)[1]

Superfamily: †Megalosauroidea

Family: †Megalosauridae

Subfamily: †Megalosaurinae

Genus: †Megalosaurus

Species: †M. bucklandii

Megalosaurus bucklandii is a species of non-avian carnivorous theropod that lived in the Middle Jurassic of England ~166 million years ago. It was the first non-avian dinosaur to have ever been given a valid scientific name.[2]

Description and paleobiology:

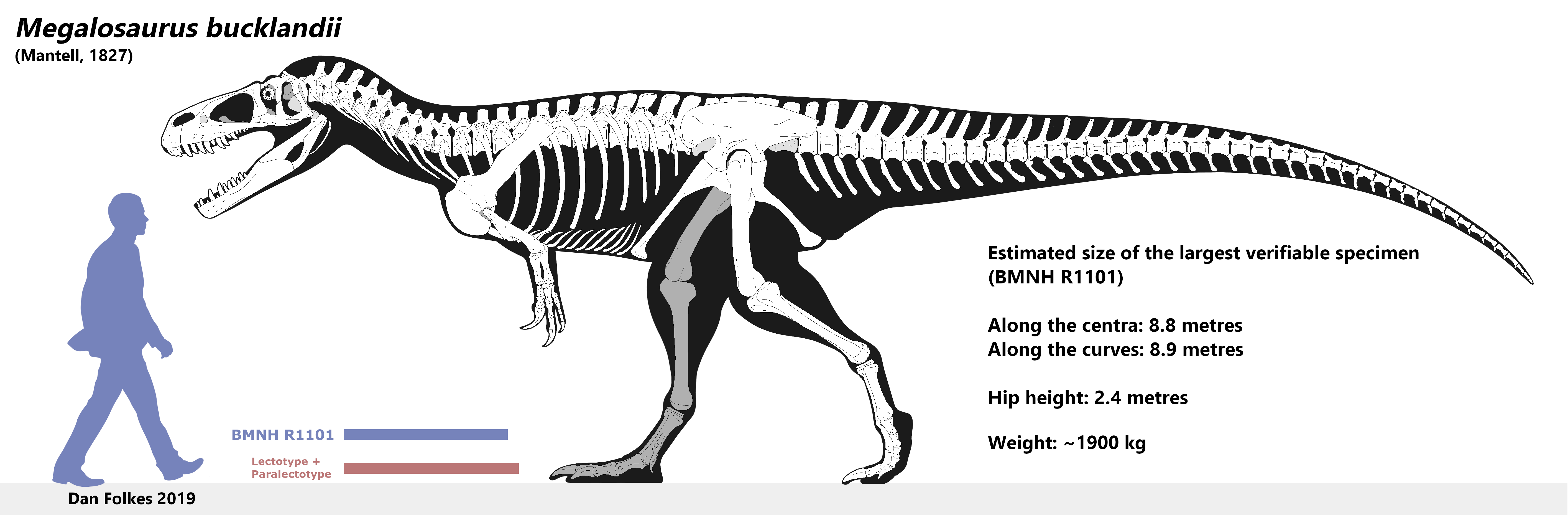

After nearly two centuries of research on theropods, Megalosaurus is now known to be a biped, with a horizontally-slung body and bauplan akin to those of other carnivorous non-avian theropod dinosaurs (see the subsequent section for past reconstructions). The best preserved femur is 805 mm long and has a minimum circumference of 302 mm. A 1985 equation for body mass would suggest an animal weighing ~943 kg, although this equation is known to underestimate body mass compared to 3-D modeling. Megalosaurus’ skeleton was well ossified with a relatively robust forearm. This indicates a stout, muscular animal, although the hindlimb was not as robust as that of Torvosaurus.[3]

Although the skull is incompletely known, the teeth are known to be ziphodont (recurved, serrated, lateromedially compressed) in morphology; this made the teeth suitable for slicing and ripping. The relatively robust forelimbs[3] suggest a use in holding onto prey.

Megalosaurus remains are very common in lower and middle Bathonian deposits from England, and are found in multiple different localities. These remains comprise a high proportion of theropod remains recovered from English Bathonian deposits. As such, Megalosaurus was probably the most abundant large predator in the faunas it was present in, and likely the apex predator of the ecosystems it inhabited.[3]

A modern skeletal reconstruction of M. bucklandii. © @ Scott Hartman->.

Discovery, naming, and phylogeny:

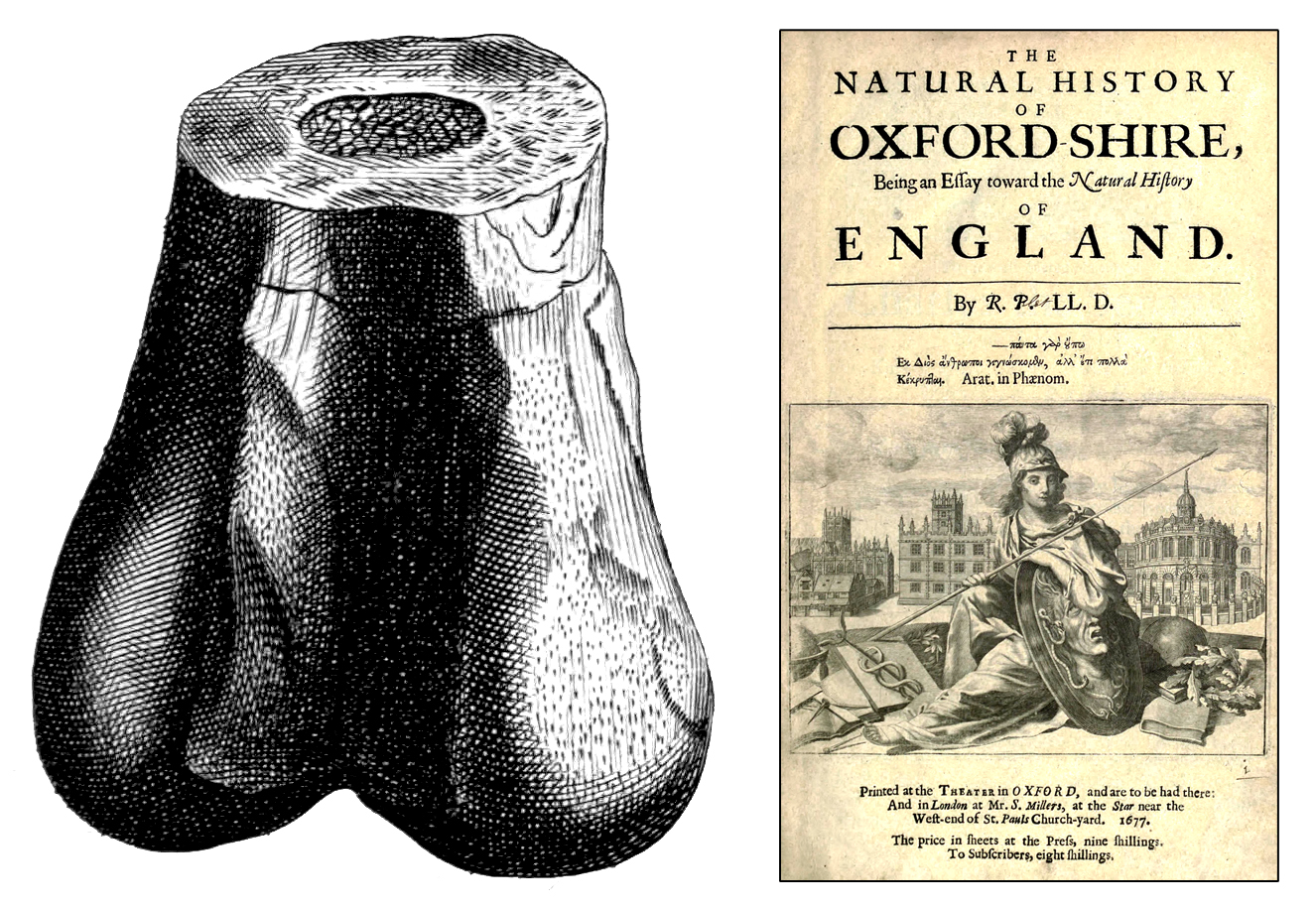

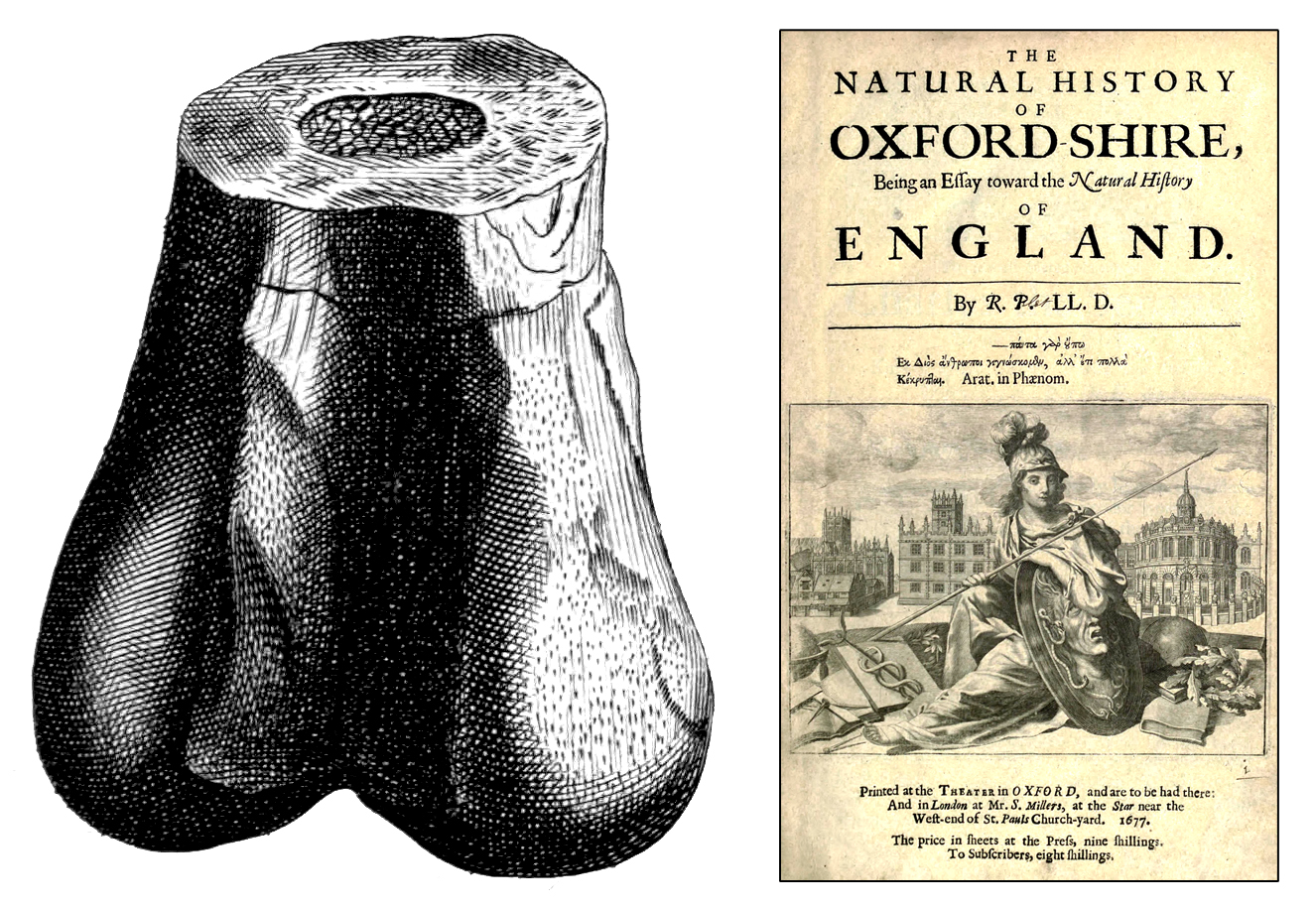

The first discovery of a bone from Megalosaurus was made in 1677.[4] The bone was the lower end of a femur recovered from the Taynton Limestone Formation[5] and described by Robert Plot. At first he wondered if it was a bone from a war elephant introduced to Britain during the Roman invasions, but he soon discounted this idea after noting its dissimilarities to elephant bones. Plot then interpreted the bone as belonging to a giant.

“There happily came to Oxford while I was writing of this, a living Elephant to be shown publickly at the ACT, An. 1676, with whose Bones … I compared ours; and found those of the Elephant not only of a different Shape, but also incomparably different to ours, though the Beast were very young and not half grown. If then they are neither the Bones of Horses, Oxen, nor Elephants, as I am strongly persuaded they are not … It remains, that (notwithstanding their extravagant Magnitude) they must have been the bones of Men or Women: Nor doth any thing hinder but they may have been so, provided it be clearly made out, that there have been Men and Women of proportionable Stature in all Ages of the World, down even to our own Days” (Plot, 1677, p. 137).[6]

The bone was dubbed “Scrotum humanum” in 1763 by Richard Brookes, given its resemblance to a scrotum containing testicles.[7] Although the bone was lost sometime later, modern paleontologists have gone as far as to say that it is obvious the bone is from a Megalosaurus, judging from contemporary drawings.[8] “Scrotum humanum” is sometimes said to be an example of a nomen oblitum, but only an established Linnaean scientific name can become a nomen oblitum. Because Brookes did not use Linnaean names in his own classification, “Scrotum humanum” was never an established name to begin with[9], hence the present day use of Megalosaurus bucklandii.

An illustration of “Scrotum humanum” next to the cover of the book Robert Plot first gave his interpretation of the bone. Image source->.

The species’ current valid binomial name was given in 1827 by Gideon Mantell, obviously naming it after William Buckland and his prior research on subsequent Megalosaurus remains.[10] Megalosaurus was originally estimated by William Buckland to have been 60-70 feet long[2] (we now know this size to be an exaggeration) and thought to be a quadruped.

During the 19th century, Megalosaurus was sometimes depicted coexisting with and battling Iguanodon, another one of the earliest described non-avian dinosaurs; Iguanodon is now known to have lived in the Early Cretaceous several millions of years after the Middle Jurassic Megalosaurus. Later in the 19th century, it was known that Megalosaurus was bipedal.

The Crystal Palace Megalosaurus. Image source->.

References:

[1] Rauhut, O. W., & Pol, D. (2019). Probable basal allosauroid from the early Middle Jurassic Cañadón Asfalto Formation of Argentina highlights phylogenetic uncertainty in tetanuran theropod dinosaurs. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1-9.

[2] Buckland, W. (1824). Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard from Stonesfield. Transactions of the Geological Society of London. 2. 1 (2): 390–396. doi:10.1144/transgslb.1.2.390.

[3] Benson, R. B. (2010). A description of Megalosaurus bucklandii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bathonian of the UK and the relationships of Middle Jurassic theropods. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 158(4), 882-935.

[4] Plot, R. (1677). “The Natural History of Oxford-shire, Being an Essay Toward the Natural History of England“. Mr. S. Miller’s: 142. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.23488.

[5] paleobiodb.org/classic/basicCollectionSearch?collection_no=59357

[6] “Robert Plot: A brief biography of this important geologists life and work“ (PDF). Oxford University Museum of Natural History. p. 4. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

[7] Brookes, R. (1763). "A New and Accurate System of Natural History: The Natural History of Waters, Earths, Stones, Fossils, and Minerals with their Virtues, Properties and Medicinal Uses, to which is added, the Method in which Linnaeus has treated these subjects". J. Newberry. 5: 364.

[8] Norell, M. A. (2019). The World of Dinosaurs: An Illustrated Tour. University of Chicago Press. p. 25.

[9] Welter-Schultes, F. W. (2013). Guidelines for the capture and management of digital zoological names information. GBIF. p. 67.

[10] Mantell, G. (1827). Illustrations of the geology of Sussex: a general view of the geological relations of the southeastern part of England, with figures and descriptions of the fossils of Tilgate Forest. London: Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. p. 92.

Life reconstruction of Megalosaurus feeding on a carcass. © @ Mark Witton->.

Temporal range: Middle Jurassic; Bathonian age (166 Ma)

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Class: Reptilia or Clade: Sauropsida

Clade: Eureptilia

Clade: Romeriida

Clade: Diapsida

Clade: Neodiapsida

Clade: Archelosauria

Clade: Archosauromorpha

Clade: Archosauriformes

Clade: Crurotarsi

Clade: Archosauria

Clade: Avemetatarsalia

Clade: Ornithodira

Clade: Dinosauromorpha

Clade: Dinosauriformes

Clade: Dinosauria

Order: Saurischia

Clade: Eusaurischia

Suborder: Theropoda

Clade: Neotheropoda

Clade: Averostra

Clade: Tetanurae

Clade: Orionides

Clade: Avetheropoda

Clade: †Carnosauria(?)[1]

Superfamily: †Megalosauroidea

Family: †Megalosauridae

Subfamily: †Megalosaurinae

Genus: †Megalosaurus

Species: †M. bucklandii

Megalosaurus bucklandii is a species of non-avian carnivorous theropod that lived in the Middle Jurassic of England ~166 million years ago. It was the first non-avian dinosaur to have ever been given a valid scientific name.[2]

Description and paleobiology:

After nearly two centuries of research on theropods, Megalosaurus is now known to be a biped, with a horizontally-slung body and bauplan akin to those of other carnivorous non-avian theropod dinosaurs (see the subsequent section for past reconstructions). The best preserved femur is 805 mm long and has a minimum circumference of 302 mm. A 1985 equation for body mass would suggest an animal weighing ~943 kg, although this equation is known to underestimate body mass compared to 3-D modeling. Megalosaurus’ skeleton was well ossified with a relatively robust forearm. This indicates a stout, muscular animal, although the hindlimb was not as robust as that of Torvosaurus.[3]

Although the skull is incompletely known, the teeth are known to be ziphodont (recurved, serrated, lateromedially compressed) in morphology; this made the teeth suitable for slicing and ripping. The relatively robust forelimbs[3] suggest a use in holding onto prey.

Megalosaurus remains are very common in lower and middle Bathonian deposits from England, and are found in multiple different localities. These remains comprise a high proportion of theropod remains recovered from English Bathonian deposits. As such, Megalosaurus was probably the most abundant large predator in the faunas it was present in, and likely the apex predator of the ecosystems it inhabited.[3]

A modern skeletal reconstruction of M. bucklandii. © @ Scott Hartman->.

Discovery, naming, and phylogeny:

The first discovery of a bone from Megalosaurus was made in 1677.[4] The bone was the lower end of a femur recovered from the Taynton Limestone Formation[5] and described by Robert Plot. At first he wondered if it was a bone from a war elephant introduced to Britain during the Roman invasions, but he soon discounted this idea after noting its dissimilarities to elephant bones. Plot then interpreted the bone as belonging to a giant.

“There happily came to Oxford while I was writing of this, a living Elephant to be shown publickly at the ACT, An. 1676, with whose Bones … I compared ours; and found those of the Elephant not only of a different Shape, but also incomparably different to ours, though the Beast were very young and not half grown. If then they are neither the Bones of Horses, Oxen, nor Elephants, as I am strongly persuaded they are not … It remains, that (notwithstanding their extravagant Magnitude) they must have been the bones of Men or Women: Nor doth any thing hinder but they may have been so, provided it be clearly made out, that there have been Men and Women of proportionable Stature in all Ages of the World, down even to our own Days” (Plot, 1677, p. 137).[6]

The bone was dubbed “Scrotum humanum” in 1763 by Richard Brookes, given its resemblance to a scrotum containing testicles.[7] Although the bone was lost sometime later, modern paleontologists have gone as far as to say that it is obvious the bone is from a Megalosaurus, judging from contemporary drawings.[8] “Scrotum humanum” is sometimes said to be an example of a nomen oblitum, but only an established Linnaean scientific name can become a nomen oblitum. Because Brookes did not use Linnaean names in his own classification, “Scrotum humanum” was never an established name to begin with[9], hence the present day use of Megalosaurus bucklandii.

An illustration of “Scrotum humanum” next to the cover of the book Robert Plot first gave his interpretation of the bone. Image source->.

The species’ current valid binomial name was given in 1827 by Gideon Mantell, obviously naming it after William Buckland and his prior research on subsequent Megalosaurus remains.[10] Megalosaurus was originally estimated by William Buckland to have been 60-70 feet long[2] (we now know this size to be an exaggeration) and thought to be a quadruped.

During the 19th century, Megalosaurus was sometimes depicted coexisting with and battling Iguanodon, another one of the earliest described non-avian dinosaurs; Iguanodon is now known to have lived in the Early Cretaceous several millions of years after the Middle Jurassic Megalosaurus. Later in the 19th century, it was known that Megalosaurus was bipedal.

The Crystal Palace Megalosaurus. Image source->.

References:

[1] Rauhut, O. W., & Pol, D. (2019). Probable basal allosauroid from the early Middle Jurassic Cañadón Asfalto Formation of Argentina highlights phylogenetic uncertainty in tetanuran theropod dinosaurs. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1-9.

[2] Buckland, W. (1824). Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard from Stonesfield. Transactions of the Geological Society of London. 2. 1 (2): 390–396. doi:10.1144/transgslb.1.2.390.

[3] Benson, R. B. (2010). A description of Megalosaurus bucklandii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bathonian of the UK and the relationships of Middle Jurassic theropods. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 158(4), 882-935.

[4] Plot, R. (1677). “The Natural History of Oxford-shire, Being an Essay Toward the Natural History of England“. Mr. S. Miller’s: 142. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.23488.

[5] paleobiodb.org/classic/basicCollectionSearch?collection_no=59357

[6] “Robert Plot: A brief biography of this important geologists life and work“ (PDF). Oxford University Museum of Natural History. p. 4. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

[7] Brookes, R. (1763). "A New and Accurate System of Natural History: The Natural History of Waters, Earths, Stones, Fossils, and Minerals with their Virtues, Properties and Medicinal Uses, to which is added, the Method in which Linnaeus has treated these subjects". J. Newberry. 5: 364.

[8] Norell, M. A. (2019). The World of Dinosaurs: An Illustrated Tour. University of Chicago Press. p. 25.

[9] Welter-Schultes, F. W. (2013). Guidelines for the capture and management of digital zoological names information. GBIF. p. 67.

[10] Mantell, G. (1827). Illustrations of the geology of Sussex: a general view of the geological relations of the southeastern part of England, with figures and descriptions of the fossils of Tilgate Forest. London: Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. p. 92.