Post by Deleted on Jul 17, 2013 21:06:29 GMT 5

Skull Ecomorphology of Megaherbivorous Dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (Upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada

"Megaherbivorous dinosaur coexistence on the Late Cretaceous island continent of Laramidia has long puzzled researchers, owing to the mystery of how so many large herbivores (6–8 sympatric species, in many instances) could coexist on such a small (4–7 million km2) landmass. Various explanations have been put forth, one of which–dietary niche partitioning–forms the focus of this study. Here, we apply traditional morphometric methods to the skulls of megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta to infer the ecomorphology of these animals and to test the niche partitioning hypothesis. We find evidence for niche partitioning not only among contemporaneous ankylosaurs, ceratopsids, and hadrosaurids, but also within these clades at the family and subfamily levels. Consubfamilial ceratopsids and hadrosaurids differ insignificantly in their inferred ecomorphologies, which may explain why they rarely overlap stratigraphically: interspecific competition prevented their coexistence."

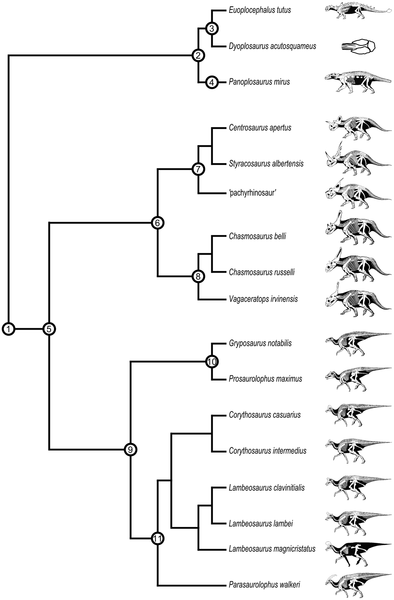

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationships of megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation.

Suprageneric taxonomy:

1, Genasauria

2, Ankylosauria

3, Ankylosauridae

4, Nodosauridae

5, Cerapoda

6, Ceratopsidae

7, Centrosaurinae

8, Chasmosaurinae

9, Hadrosauridae

10, Hadrosaurinae

11, Lambeosaurinae

After Butler et al., Prieto-Márquez, Sampson et al., and Thompson et al.

Skeletal drawings (not to scale) by G. S. Paul (used with permission).

Figure 2. Linear measurements used in this study (compare with Table 1).

A, ankylosaur skull in left lateral (left) and caudal (right) views

B, ceratopsid skull in left lateral (left) and caudal (right) views

C, hadrosaurid skull in left lateral (left) and caudal (right) views

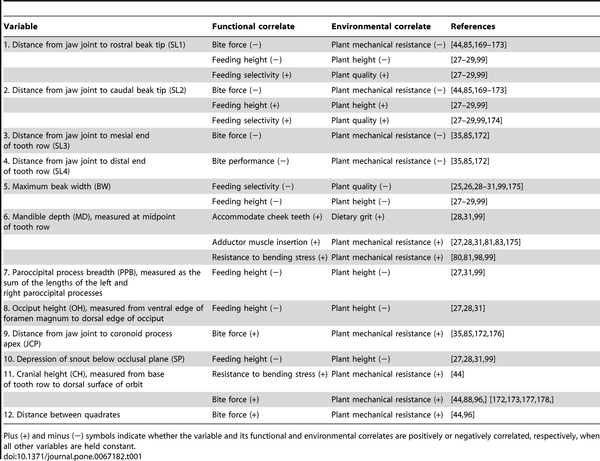

Table 1. Form-function complex of the herbivore skull (compare with Figure 1).

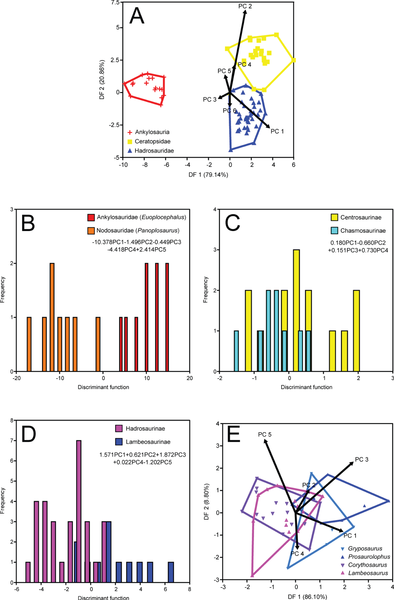

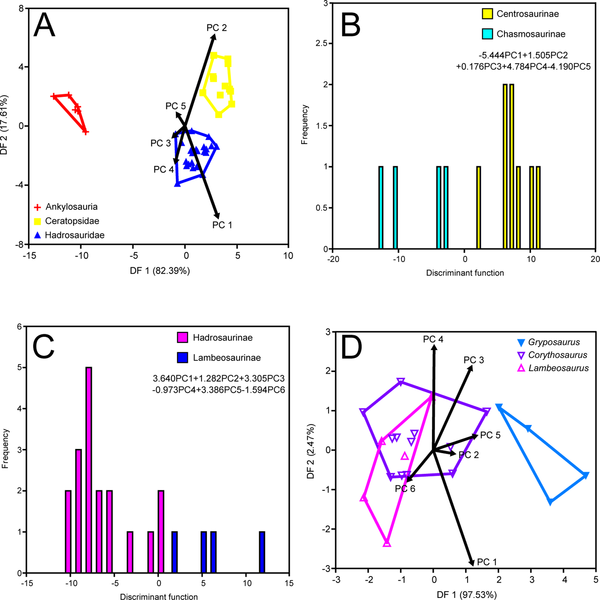

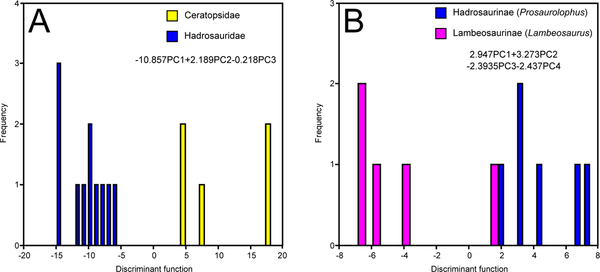

Figure 3. Time-averaged DFAs.

A, coarse-scale analysis

B, ankylosaur family analysis

C, ceratopsid subfamily analysis

D, hadrosaurid subfamily analysis

E, hadrosaurid genus analysis

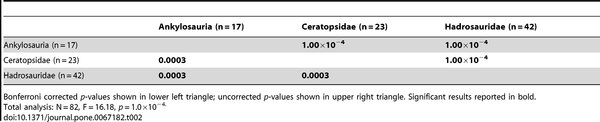

Table 2. NPMANOVA results for the time-averaged coarse scale (suborder/family) taxonomic comparisons (10,000 permutations).

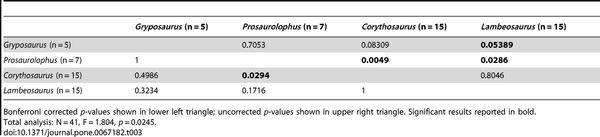

Table 3. NPMANOVA results for the time-averaged hadrosaurid genus comparisons (10,000 permutations).

Figure 4. Time-constrained MAZ-1 DFAs.

A, coarse-scale analysis

B, ceratopsid subfamily analysis

C, hadrosaurid subfamily analysis

D, hadrosaurid genus analysis

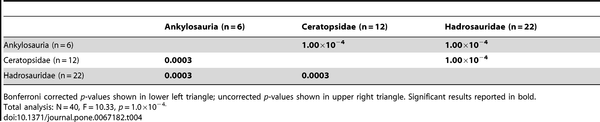

Table 4. NPMANOVA results for the MAZ-1 coarse scale (suborder/family) taxonomic comparisons (10,000 permutations).

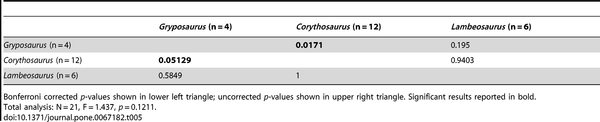

Table 5. NPMANOVA results for the MAZ-1 hadrosaurid genus comparisons (10,000 permutations).

Figure 5. Time-constrained MAZ-2 DFAs.

A, coarse-scale analysis

B, hadrosaurid analysis

Figure 6. Depiction of dietary niche partitioning among megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the DPF (MAZ-2).

Left to right: Chasmosaurus belli, Lambeosaurus lambei, Styracosaurus albertensis, Euoplocephalus tutus, Prosaurolophus maximus, Panoplosaurus mirus. A herd of S. albertensis looms in the background. Image courtesy of J.T. Csotonyi.

"Megaherbivorous dinosaur coexistence on the Late Cretaceous island continent of Laramidia has long puzzled researchers, owing to the mystery of how so many large herbivores (6–8 sympatric species, in many instances) could coexist on such a small (4–7 million km2) landmass. Various explanations have been put forth, one of which–dietary niche partitioning–forms the focus of this study. Here, we apply traditional morphometric methods to the skulls of megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta to infer the ecomorphology of these animals and to test the niche partitioning hypothesis. We find evidence for niche partitioning not only among contemporaneous ankylosaurs, ceratopsids, and hadrosaurids, but also within these clades at the family and subfamily levels. Consubfamilial ceratopsids and hadrosaurids differ insignificantly in their inferred ecomorphologies, which may explain why they rarely overlap stratigraphically: interspecific competition prevented their coexistence."

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationships of megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation.

Suprageneric taxonomy:

1, Genasauria

2, Ankylosauria

3, Ankylosauridae

4, Nodosauridae

5, Cerapoda

6, Ceratopsidae

7, Centrosaurinae

8, Chasmosaurinae

9, Hadrosauridae

10, Hadrosaurinae

11, Lambeosaurinae

After Butler et al., Prieto-Márquez, Sampson et al., and Thompson et al.

Skeletal drawings (not to scale) by G. S. Paul (used with permission).

Figure 2. Linear measurements used in this study (compare with Table 1).

A, ankylosaur skull in left lateral (left) and caudal (right) views

B, ceratopsid skull in left lateral (left) and caudal (right) views

C, hadrosaurid skull in left lateral (left) and caudal (right) views

Table 1. Form-function complex of the herbivore skull (compare with Figure 1).

Figure 3. Time-averaged DFAs.

A, coarse-scale analysis

B, ankylosaur family analysis

C, ceratopsid subfamily analysis

D, hadrosaurid subfamily analysis

E, hadrosaurid genus analysis

Table 2. NPMANOVA results for the time-averaged coarse scale (suborder/family) taxonomic comparisons (10,000 permutations).

Table 3. NPMANOVA results for the time-averaged hadrosaurid genus comparisons (10,000 permutations).

Figure 4. Time-constrained MAZ-1 DFAs.

A, coarse-scale analysis

B, ceratopsid subfamily analysis

C, hadrosaurid subfamily analysis

D, hadrosaurid genus analysis

Table 4. NPMANOVA results for the MAZ-1 coarse scale (suborder/family) taxonomic comparisons (10,000 permutations).

Table 5. NPMANOVA results for the MAZ-1 hadrosaurid genus comparisons (10,000 permutations).

Figure 5. Time-constrained MAZ-2 DFAs.

A, coarse-scale analysis

B, hadrosaurid analysis

Figure 6. Depiction of dietary niche partitioning among megaherbivorous dinosaurs from the DPF (MAZ-2).

Left to right: Chasmosaurus belli, Lambeosaurus lambei, Styracosaurus albertensis, Euoplocephalus tutus, Prosaurolophus maximus, Panoplosaurus mirus. A herd of S. albertensis looms in the background. Image courtesy of J.T. Csotonyi.