Post by LeopJag on Sept 19, 2013 11:31:34 GMT 5

Wikipedia

pterodectyle:

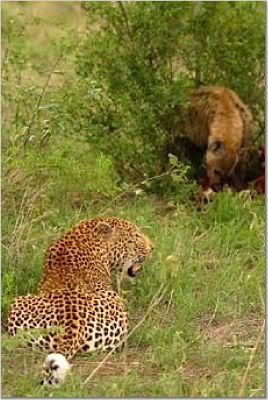

In what could perhaps be considered the sighting of the month, rangers and guests were treated to an astounding display of savagery by the Hlarulini Male leopard. He was initially found moving southwards through the southern parts of the open area commonly referred to as The Golf Course. He soon arrived at an adult male impala carcass . The problem for the male leopard was that a hyena was feeding on the impala, and initially he sat some metres off, merely watching the hyena feeding. After a few minutes he sat up and edged forward. Then rather unexpectedly, he dashed towards the hyena and attacked it. He grabbed the hyenaÂ’s head between his paws and sank his teeth into its muzzle. He wrestled the hyena to the ground and began strangling it. He held the hyena in this position for almost ten minutes, and eventually the hyena stopped struggling The leopard then released the motionless creature, collected his impala kill, and moved northwards. Everyone at the sighting thought that the hyena was dead, but upon closer inspection, it became evident that it was still breathing slightly. Over the course of half-an-hour, the hyenaÂ’s breathing increased slowly. It eventually managed to get to its feet, but appeared very wobbly. It gathered itself, and then walked off, appearing relatively unscathed.

www.malamala.tv/LEOP_hlarulini06.htm

In what could perhaps be considered the sighting of the month, rangers and guests were treated to an astounding display of savagery by the Hlarulini Male leopard. He was initially found moving southwards through the southern parts of the open area commonly referred to as The Golf Course. He soon arrived at an adult male impala carcass . The problem for the male leopard was that a hyena was feeding on the impala, and initially he sat some metres off, merely watching the hyena feeding. After a few minutes he sat up and edged forward. Then rather unexpectedly, he dashed towards the hyena and attacked it. He grabbed the hyenaÂ’s head between his paws and sank his teeth into its muzzle. He wrestled the hyena to the ground and began strangling it. He held the hyena in this position for almost ten minutes, and eventually the hyena stopped struggling The leopard then released the motionless creature, collected his impala kill, and moved northwards. Everyone at the sighting thought that the hyena was dead, but upon closer inspection, it became evident that it was still breathing slightly. Over the course of half-an-hour, the hyenaÂ’s breathing increased slowly. It eventually managed to get to its feet, but appeared very wobbly. It gathered itself, and then walked off, appearing relatively unscathed.

www.malamala.tv/LEOP_hlarulini06.htm

Additional Info -

Diet -

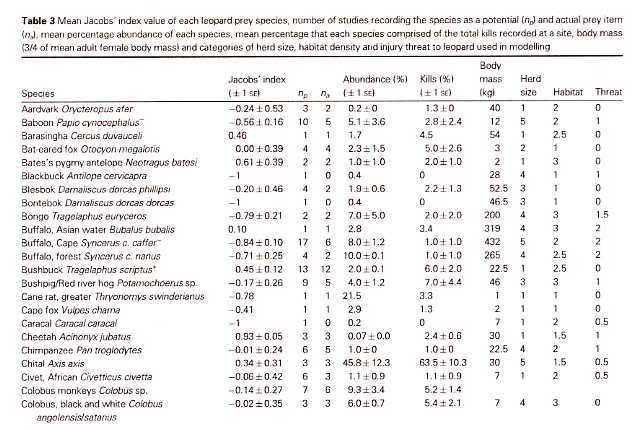

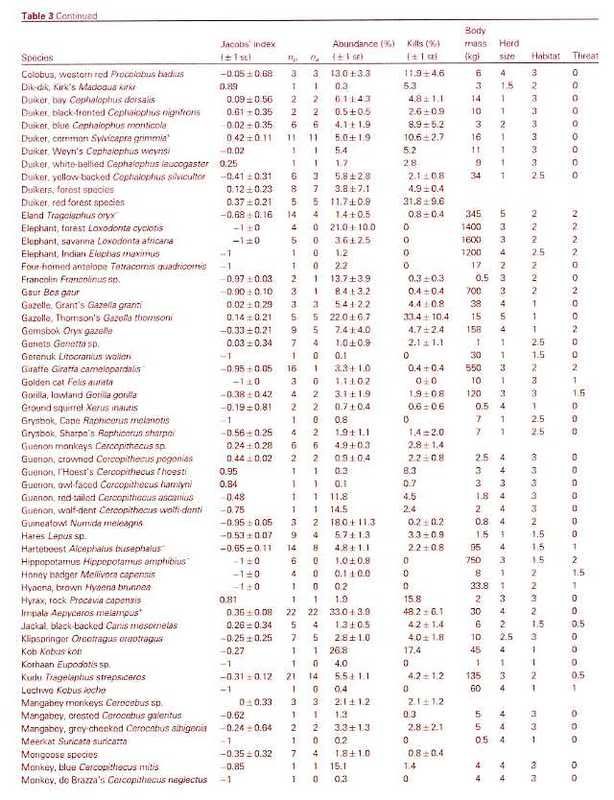

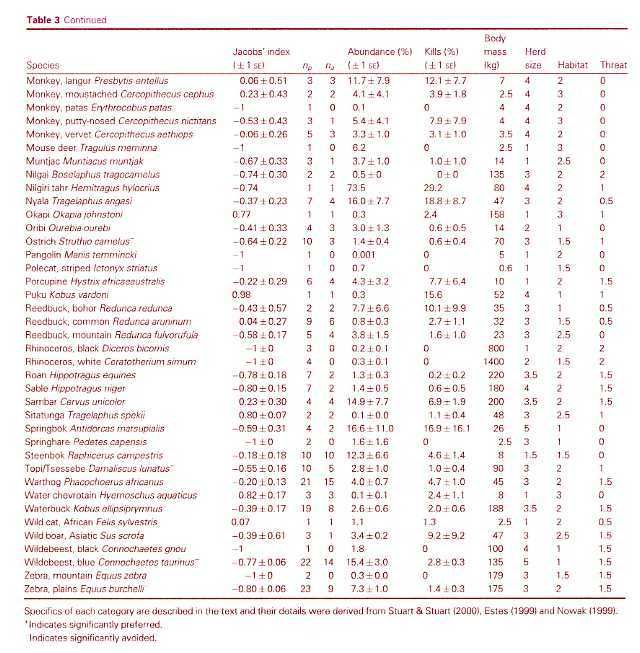

The known prey of the leopard ranges from dung beetles (Fey 1964) to adult male eland (Kingdon 1977), which can reach 900 kg (Stuart and Stuart 1992a). Bailey (1993) found that at least 92 prey species have been documented in the leopardÂ’s diet in sub-Saharan Africa. The flexibility of the diet is illustrated by HamiltonÂ’s (1976) analysis of leopard scats from KenyaÂ’s Tsavo West National Park, of which 35% contained rodents, 27% birds, 27% small antelopes, 12% large antelopes, 10% hyraxes and hares, and 18% arthropods. Seidensticker (1991a) and Bailey (1993) reviewed the literature, and concluded that leopards generally focus their hunting activity on locally abundant medium-sized ungulate species in the 20-80 kg range, while opportunistically taking other prey. For example, analysis of leopard scats from a Kruger NP study area found that 67% contained ungulate remains, of which 60% were impala, the most abundant antelope, with adult weights of 40-60 kg. Small mammal remains were found most often in scats of sub-adult leopards, especially females (Bailey 1993). Studies have found average intervals between ungulate kills to range from seven (Bailey 1993) to 12-13 days (Hamilton 1976, Le Roux and Skinner 1989). Bailey (1993) estimated average daily consumption rates at 3.5 kg for adult males and 2.8 kg for females.

Colour Variations

In general, the coat color varies from pale yellow to deep gold or tawny, and is patterned with black rosettes. The head, lower limbs and belly are spotted with solid black. Coat color and patterning are broadly associated with habitat type. Pocock (1932a) found the following trends in coloration for leopards in Africa:

savannah leopards - rufous to ochraceous in color;

desert leopards - pale cream to yellow-brown in color, with those from cooler regions being more grey;

rainforest leopards - dark, deep gold in color;

high mountain leopards - even darker in color than 3).

Black leopards (the so-called "black panthers") occur most frequently in humid forest habitats (Kingdon 1977), but are merely a color variation, not a subspecies.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mortality in a protected Leopard population, Phinda Private Game Reserve, South Africa: A population in decline?

Guy Balme & Luke Hunter

Abstract

We investigated the causes and rates of mortality in a protected Leopard population in the Phinda Private Game

Reserve, South Africa. Data from 16 radio-tagged Leopards and their cubs were used to determine the causes of

mortality and annual mortality rates for various age and sex classes in the population. Intra-specific strife accounted for

the greatest number of deaths followed by human-related mortality. Males died mainly as a result of human activity

whereas females died from natural causes. The mortality rate for males was significantly higher than for females, and

the annual mortality rate for the population was higher than any previously recorded in Leopards. Rapid turnover of

adult males due to human persecution may have reduced recruitment into the population because social instability

prevented females from raising cubs. If the present rates of mortality and recruitment are maintained, Phinda may

represent a population sink for Leopards with poor conservation and tourism prospects.

Introduction

Leopards are often killed as perceived or real problem animals, or by commercial trophy hunting operations. Despite electrified game-fencing along most borders, Leopards move freely between adjacent properties and, because Phinda is long and narrow, few individual Leopards have their entire home range

within the boundaries of the reserve (Balme & Hunter, unpub. data). The result is that most individual Leopards considered protected on Phinda are actually exposed to high levels of hunting due to frequent movements off the reserve.

In this paper, we present the results of the first 29 months of the study, addressing three main questions:

1. What are the causes of mortality to Leopards in the Phinda population?

2. What is the annual mortality rate of the Phinda Leopard population for different age and sex classes?

3. Does Phinda effectively protect Leopards?

Results:

Causes of mortality

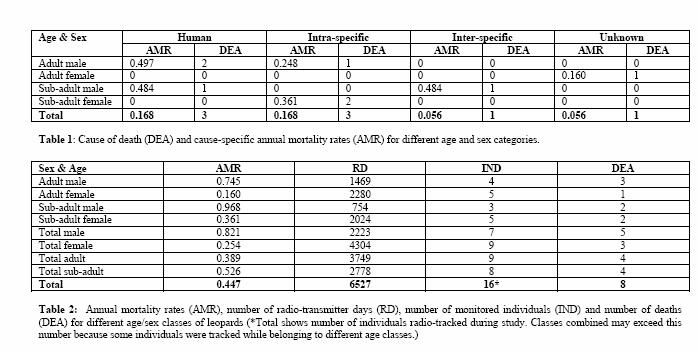

Eight radio-collared Leopards died during the study, for which the cause of death was certain or probable in seven cases (Table 1). Intra-specific conflict and anthropogenic deaths were equally important causes of mortality for adults and sub-adults combined, both claiming three individuals. Natural causes (excluding other Leopards) were responsible for one and possibly two additional deaths.

Intra-specific clashes killed one adult male and two sub-adult females. M1 was a resident territorial male when killed by the adult male, M5. The sub-adult female F10 was killed by an uncollared adult female leopard when almost three years old and displaying the first signs of territorial behaviour (‘sawing’ and scentmarking).

The sub-adult female F15 was 20 months of age when killed by a male Leopard, the sub-adult M14. Additionally, although we have not included juvenile deaths in the estimation of mortality rates, three juveniles were killed by the adult male M13 that had recently become established and was not their sire.

Human-related deaths killed three males. Two adult males M5 and M13 were established territorial males at the time of their disappearance on properties adjacent to Phinda. The sub-adult male, M7 was last located on private property near the town of Hluhluwe, approximately 11km south of PhindaÂ’s southern boundary, when his signal disappeared.

One Leopard was killed by another carnivore. The subadult male, M4 died from septicemia arising from severe bite wounds on the neck, shoulders and hindquarters. We found evidence at the site of a prolonged fight between the Leopard and an adult Spotted Hyaena Crocuta crocuta which was consistent with the bite marks.

We do not know the cause of death of the adult female F2 whose carcass we examined approximately two weeks after death when decomposition was advanced.

Mortality rates

The average annual mortality rate (AMR) of the population between April 2002 and August 2004 was 0.447 (Table 2). The mortality rate for males was significantly higher than for females (p = 0.004, df = 1). Sub-adult males (0.968) had the greatest annual mortality of any cohort, followed by adult males (0.745). Adult females had the lowest mortality rate (0.160) with only one death recorded for the study period.

Causes of mortality

Leopards at Phinda were killed chiefly by other Leopards. Two deaths (M1 and F10) were the result of territorial clashes between same-sex pairs. Leopards are known to defend their territories from same-sex intruders sometimes leading to fatalities (Le Roux & Skinner, 1989) though the proportion of deaths here caused by other Leopards is higher than reported in other detailed studies (Bailey, 1993; Stander et al., 1997). The killing of sub-adult female F15 by a subadult male (M14) is unusual, particularly as these animals had met on previous occasions. F15 was not reproductively mature and M14 typically rebuffed curious approaches from her in past encounters we observed, but his aggression was largely demonstrative and never escalated to physical contact. A similar instance of a male Leopard killing a younger female was documented at Londolozi Private Game Reserve, South Africa (Hes, 1991). Males might regard young, reproductively unavailable females as competitors for food resources and attack them as such, though it is unclear why it happened later rather than sooner in this case.

All radio-tagged Leopards that died due to humanrelated causes were males. Males are more desirable to trophy hunters due to their larger size, and males also utilise larger home ranges and cover greater daily distances than females, increasing their chances of moving off the reserve into areas where they can be hunted (Mizutani & Jewel, 1998; Hunter & Balme, unpubl. data). Importantly, as far as we know, males killed outside Phinda were not shot legally by international hunters with CITES permits. Nonetheless, all three deaths occurred during the legal trophy hunting season between April to November. This may be due to Leopards being mistaken for another legally hunted species but more likely they are killed intentionally by South Africans. Leopards are persecuted intensely by various landowners in the

region and there is little chance of prosecution for illegal killing. We do not know whether the risks for Leopards are elevated during the legal hunting season. It is likely that opportunistic killing of Leopards occurs year-round though increased numbers of local hunters seeking other species in the area during the legal season might result in more Leopards killed then.

Bailey (1993) reported that starvation (mainly of subadults) accounted for the greatest proportion of Leopard deaths in Kruger National Park (KNP). He suggested that sub-adults were more likely to starve due to a related set of factors that included a lack of hunting experience, loss of condition due to increased parasitic infestations, competition for resources with other predators, and seasonal changes in prey abundance and availability of cover. We found no evidence of starvation contributing to Leopard deaths at Phinda. One individual, M7 was emaciated at capture but this was due to serious injuries, probably incurred from a conspecific. His condition improved dramatically post-capture and he made a full recovery. He was clearly foraging successfully for 12 months following capture until February 2004 when he was killed outside Phinda.

The only adult female to die during the study probably succumbed to natural causes. At the time of her death, she was due to give birth and we made no effort to approach her, assuming she was localised with newborn cubs. By the time we decided to investigate, autolysis of the carcass was too advanced to determine a cause but there was no evidence to suggest her death was related to human activity. We found no snares and the site was not close to a boundary where the risk of snaring at Phinda is greatest. She may have died due to complications arising from birth. This is considered unusual in felids (Apps & Du Toit, 2000) but is occasionally recorded: for example, an otherwise healthy Lioness Panthera leo in Pilanesberg National Park died from secondary septicemia due to dystocia (G. van Dyk, Pers. comm.).

Implications

High levels of mortality among adult males at Phinda may have had an additive effect on mortality in the population by lowering the reproductive success of females. Although male Leopards provide no parental care to cubs, the presence of the sire allows mothers to raise cubs with a reduced risk of infanticide by foreign males (Hunter et al., in press). There are few reliable observations of infanticide in leopards (see: Ilani, 1986; 1990; Scott & Scott, 2003) but new males entering the population are likely to kill existing cubs. We saw this once during the study period, following the illegal killing of M5. The resulting vacancy was rapidly filled by the male M13 who killed the 4-month old cubs of F12 (which M5 probably sired). Although we observed infanticide only on this occasion, there was limited evidence of successful reproduction in general. During the 29-month study, we observed consorting pairs on 18 occasions involving seven adult females, multiple males and 305 actual matings, yet only seven cubs in three litters were born. Only two cubs are still alive at the time of writing, one of them still dependent on its mother.

That few cubs were produced during the study may be a further consequence of high turnover among males. In Lions, high levels of infanticide further impact reproductive output by reducing the rate at which females conceive (Packer & Pusey, 1983). Lionesses display a period of reduced fertility immediately following the take-over of a pride by a new male coalition. This presumably allows females to assess the fitness of new males and postpone conception until the males are established and the threat of another takeover is reduced. Rapid turnover of male Leopards at Phinda might be driving female Leopards into a reproductive dead-end in which cubs are killed at high rates and subsequent conception is delayed. In an isolated Leopard population in the Judean Desert, Israel, infanticide was the chief reason that not a single individual was recruited into the adult population during a five-year period (Ilani, 1986; 1990).

www.panthera.org/sites/default/files/Balme_Hunter_2004_Mortality_in_a_protected_leopard_population_in_South_Africa_0.pdf

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

More later...