|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 6, 2020 17:31:51 GMT 5

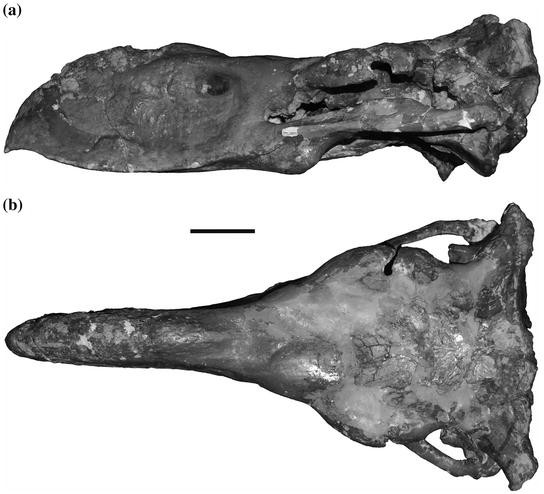

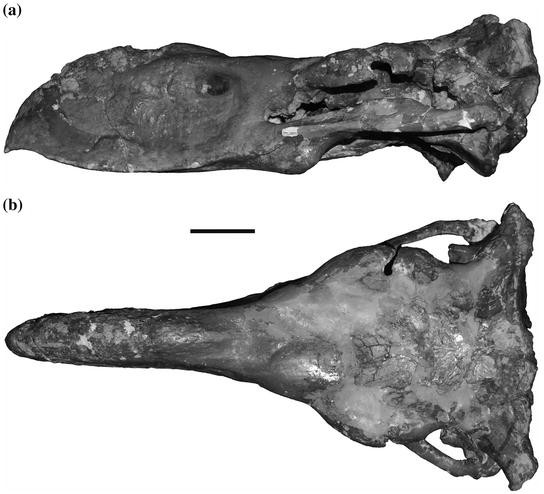

Venomous Dragon has his own varanid thread, so...why can't I have my own terror bird (phorusrhacid) thread? Because we don't seem to have any profiles for any phorusrhacid, and because I don't always have the time to create a profile and then add the information I find to it, I will use this as a general thread for dumping info I find interesting on phorusrhacids. Maybe people glancing through this thread will learn a thing or two about this family as a result too. I found out this morning that, contrary to my earlier expectations, Kelenken guillermoi's leg proportions actually plot closer to graviportal flightless birds than cursorial ones. It wasn't as graviportal as Paraphysornis, but it was still well within the graviportal side of the plot, surpassing some elephant birds in this regard to varying degrees.  Source-> Source->The authors of the source I linked to above suggest that Kelenken and Paraphysornis were slower than their more cursorial relatives, and that they probably were engaging in ambush hunting, predation upon large and slow prey (e.g. large mammals), and scavenging. So it's clear that some terror birds weren't necessarily lightly built creatures. Perhaps consistent with predation upon large animals is a look at their skulls. Andalgalornis has been found to have had a skull poorly suited to withstanding lateral loads, and looking at its paper-thin rostrum, it's not hard to see why ( 3D model->). But Kelenken and Paraphysornis seem to have had wider rostra. Below is the skull of Kelenken in dorsal view (albeit, it is crushed to a degree).  Source->Paraphysornis Source->Paraphysornis definitely had a wider rostrum than the likes of Andalgalornis.   I'll add some more info later, but I will note that Phorusrhacos also appears to differ from Andalgalornis in skull proportions to an extent, as does Devincenzia. |

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on May 7, 2020 7:03:19 GMT 5

Nice start to the thread. I'll be looking forward to learning more. Phorusrhacids are a very iconic and aptly named - terrifying - group of predatory birds. I feel the larger ones might treat an unarmed human like a crow treats a baby squirrel it happens to find.

Do you think that Brontornis belongs in the phorusrhacid family, or is an anseriform? I noticed your chart did not include Brotornis, but that is the direction.

current research appears to lean. Hard to picture such a hard core predator related to the relatively benign water fowl such as ducks, geese, and swans.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 7, 2020 8:15:48 GMT 5

Brontornis' phylogeny has bee the subject of debate over the years, it seems. The book I linked to above (the source of the graph) considers Brontornis to be in its own family (Brontornithidae) separate from the Phorusrhacidae, and a giant basal anseriform. Mind you, the book I cited is from 2017.

Brontornis might not have even been a predator; it's possible it was herbivorous. The book goes on to mention that the upper jaw of Brontornis is unknown, and that therefore there's no evidence that it had a hooked tip. Its lower beak, however, is more like that of a dromornithid or gastornithid, both of which are now considered herbivorous, and it seems to have had very powerful jaw muscles evocative of these same herbivorous birds. Oddly enough, it's the carnivorous birds (phorusrhacids and modern birds of prey) that seem to have weak bite forces, but focus on having a big, wickedly hooked beak. Also, its toe claws were apparently broad and weakly curved, unlike the raptor-like claws of the phorusrhacids.

There's actually a subsequent figure in that book that plots the limb proportions of the brontornithids with other terrestrial flightless birds (Fig. 6.6), and they plot right in the midst of the graviportal side of the plot. So they were definitely heavily-built forms; only moas and seemingly one elephant bird surpass them in this regard.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 7, 2020 20:09:05 GMT 5

Phorusrhacos' rostrum appears to be wider than that of Andalgalornis. Here is the former's skull in dorsal view (from Degrange et al., 2019).  Andalgalornis Andalgalornis' skull (from Degrange et al., 2011).  Here's a screenshot I took of the 3D model of Andalgalornis' skull in dorsal view (again, you can check out and explore this model for yourself in the hyperlink that says "3D model" in the OP).  Look particularly at the very top of the rostrum. Notice how really paper thin Andalgalornis' beak is, and how the very top of the rostrum of Phorusrhacos seems to be significantly wider. The palatine region and the bottom of the rostrum also seem to be markedly wider in Phorusrhacos. This is the skull of P. longissimus. Unfortunately, it's not a perfect ventral view, but you can still gain some perspective of how far apart the ventral rostral margins are from each other, and the width of the palatine region.  commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phorusrhacos_longissimus_5.jpg commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phorusrhacos_longissimus_5.jpgI tried to approximate this view with the Andalgalornis 3D model as best as I could. This is what Andalgalornis looks like in comparison.  The beak of Andalgalornis, again, appears markedly narrower.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 8, 2020 3:15:01 GMT 5

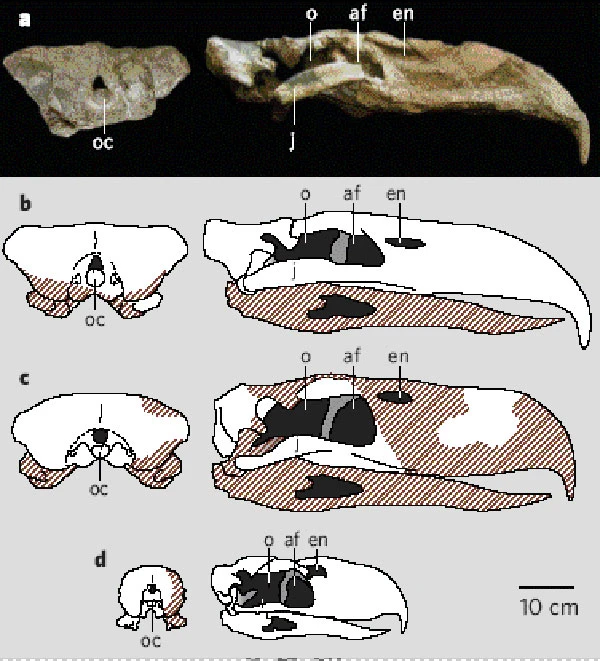

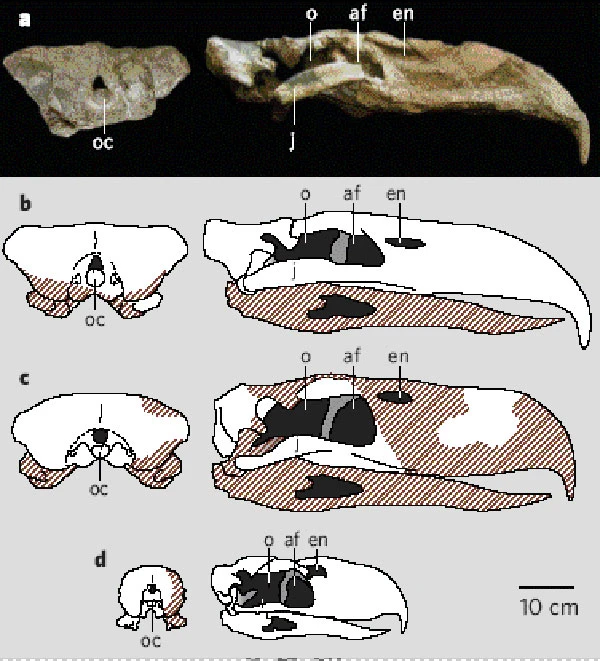

The skull of Devincenzia pozzi in dorsal view (from Tambussi & Degrange, 2012). The width of its rostrum seems to be more like that of its fellow phorusrhacine Phorusrhacos than the patagornithine Andalgalornis.  Now, deviating from the rostrum, which I focused on in two of my previous posts, here is a comparison of the occipital tables of phorusrhacines and patagornithines (from Chiappe & Bertelli, 2006).  a and b both show Kelenken, c is Devincenzia, and d is Patagornis. Notice the wide, rectangular occipital tables of the two phorusrhacines, while that of Patagornis is circular-ish and not very expanded laterally. Who else has this latter morphology of the occipital table? You guessed it: the fellow patagornithine Andalgalornis (screen capture from the 3D model linked in the OP).  So, what was my point in bringing up these comparisons between different terror bird subfamilies in these last three posts? Andalgalornis has been found to have had a skull/beak with strong dorsoventral strength, but weak lateral strength. It has been suggested that either this species focused on small prey or, if it hunted large prey, it must have used repeated precise blows with its beak to kill its victims. While this may hold true for Andalgalornis (and perhaps its closest patagornithine relatives), the skulls of phorusrhacines appear to exhibit wider, thicker bills with the posterior region of the skull significantly more expanded laterally. It could be that phorusrhacines were better adapted for hunting and struggling with large prey. Indeed, Kelenken, as I've shown in the OP, was one of the stouter-legged, graviportal phorusrhacids, so it doesn't seem like it was particularly well equipped to chase after small prey to begin with. The authors of the Andalgalornis skull biomechanics paper also suggest that restraining prey with the feet was potentially an option " ...despite the absence of sharp talons." This, of course, is blatantly false; phorusrhacids are established as having raptorial claws on their feet. darrennaish.blogspot.com/2006/11/more-on-phorusrhacids-biggest-fastest.htmlBlanco & Jones (2005)Source is the same book I hyperlinked to in the OP. |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 17, 2020 20:29:34 GMT 5

On competition with other predators and extinction:In South America, where phorusrhacids appear to have been most prominent in (there is one species known from Europe, but that's about it, I think), they coexisted with predatory sparassodonts (metatherians that were sister taxa to the marsupials) and terrestrial predatory sebecosuchians. Supposedly, phorusrhacids seem to have outcompeted wolf-like metatherian predators at some point in open environments. [1] Any further information on this would be appreciated. I do not know what happened to the sebecosuchians, which went extinct in the Middle Miocene. Just in general, the idea that the endemic South American apex predators were all outcompeted by North American arrivals during the Great American Biotic Interchange is not well supported today. As mentioned above, the sebecosuchians were obviously long extinct by this point. Sparassodonts also seem to have become extinct before ever getting the chance to meet their placental ecological counterparts. The last thylacosmilids disappeared >1.5 million years before the appearance of machairodontines (believed to be their placental ecological vicars) in South America; the last hathliacynids went extinct a million years before mustelids and canids show up in South America's fossil record; borhyaenines went extinct no less than 4 million years before canids show up in South America's fossil record, and 5 million years before felids do; and the last decidedly omnivorous "prothylacinines" disappeared 5 million years before ursids show up in South America's fossil record. Only procyonids had a chance of competing with and possibly displacing them. [2][3] A supposed mustelid in the Huayquerian of Argentina (3-4 million years before their previously-thought point of arrival in SA) was later shown to be a didelphimorphian marsupial. [4] The only native terrestrial South American apex predators that indeed definitively lived through the peak of the GABI are, as you've probably guessed given the focus of this thread, the phorusrhacids. Titanis walleri seems to be the only phorusrhacid known to have migrated to North America. Its earliest record dates to ~5 million years ago in Texas, so phorusrhacids were already settled in North America by that time (they likely island-hopped through Central America and the Caribbean sometime before this). [5] There seem to have been other phorusrhacid species still residing in South America at around this time (e.g. Devincenzia is known from the early Pliocene, and at least a couple mesembriornithines [6]), but there doesn't seem to be any evidence for them migrating to North America, or any later records of them. Titanis' first record in Florida dates to ~2.2 million years ago, but its last record in Florida (and seemingly its last record ever) dates to ~1.8 million years ago. For some reason, the authors of the paper I just now cite postulate that Titanis succumbed to competition with carnivorans, despite the implication from their own evidence that T. walleri coexisted and competed with carnivorans for ~3.2 million years (the book I cited above simply piggybacks off of MacFadden et al.). [5] The latest source I have cited ( [6]) seems to at least take this into account. It also mentions a proposal that competition with condors played a role in their extinction (a hypothesis I've never heard of until now), which it also criticizes for the same reasons as with competition with predatory mammals [6]. I'll also bring this up again: terrestrial predatory scavengers are unlikely (as we should all know by now). And if the Late Miocene Argentavis magnificens is any indication, phorusrhacids have already weathered out large soaring scavenging birds. Currently, T. walleri's fossil record is only known from North America. Taking the currently known fossil record at face value, this would suggest that Titanis didn't just simply meet predatory mammals, it never knew a world without them. If Titanis was living with carnivorans for literally its entire existence, it should be self-evident that carnivorans were not the reason behind its extinction. Evidence suggests psilopterine phorusrhacids (particularly Psilopterus itself) persisted into the Late Pleistocene (96,040 ± 6,300 years ago). [7] Psilopterus was small, and certainly would have been no apex predator, but whatever competition it might have endured from other small predators that migrated from North America, it seems to have endured it for quite a while. References:[1] Antón, M. (2013). Sabertooth. Indiana University Press. p. 61. [2] Forasiepi, A. M., Martinelli, A. G., & Goin, F. J. (2007). Revisión taxonómica de Parahyaenodonargentinus Ameghino y sus implicancias en el conocimiento de los grandes mamíferos carnívoros del Mio-Plioceno de América de Sur. Ameghiniana, 44(1), 143-159. [3] Forasiepi, A. M. (2009). Osteology of Arctodictis sinclairi (Mammalia, Metatheria, Sparassodonta) and phylogeny of Cenozoic metatherian carnivores from South America. Monografías del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, 6, 1-174. [4] Prevosti, F. J., & Pardiñas, U. F. (2009). Comment on “The oldest South American Cricetidae (Rodentia) and Mustelidae (Carnivora): Late Miocene faunal turnover in central Argentina and the Great American Biotic Interchange” by DH Verzi and CI Montalvo [Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 267 (2008) 284–291]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 280(3-4), 543-547. [5] MacFadden, B. J., Labs-Hochstein, J., Hulbert Jr, R. C., & Baskin, J. A. (2007). Revised age of the late Neogene terror bird (Titanis) in North America during the Great American Interchange. Geology, 35(2), 123-126. [6] Mayr, G. (2016). Avian evolution: the fossil record of birds and its paleobiological significance. John Wiley & Sons. pp 192-193. [7] Jones, W., Rinderknecht, A., Alvarenga, H., Montenegro, F., & Ubilla, M. (2018). The last terror birds (Aves, Phorusrhacidae): New evidence from the late Pleistocene of Uruguay. PalZ, 92(2), 365-372.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 20, 2020 1:36:46 GMT 5

Okay, in my last post I said " There seem to have been other phorusrhacid species still residing in South America at around this time [~5 million years ago] (e.g. Devincenzia is known from the early Pliocene, and at least a couple mesembriornithines[6]), but there doesn't seem to be any evidence for them migrating to North America, or any later records of them". I should probably make an amendment to this statement. Of course the youngest record of South American phorusrhacids isn't from the Early Pliocene; Jones et al. (2018) dating phorusrhacids to the Late Pleistocene makes this clear. What I meant was that there doesn't seem to be any later record of large apex predatory phorusrhacids in South America than the Early Pliocene. As it turns out, though, it seems I was wrong. There is a complete right tibiotarsus (MNHN-1563) from a phorusrhacine found in the Raigón Formation of Uruguay. It is noted as being similar to that of Phorusrhacos, but larger ( Tambussi et al., 1999). This formation is said to age from the Pliocene to Early Pleistocene by the study. Degrange (2012) estimates Phorusrhacos at ~120 kg in body mass ( link->). It might be reasonable to assume that this bird, given its larger tibiotarsus, would have been larger. Here's what Tambussi et al. say about age and the remains associated with the formation. The Ensenadan ranges from 1.2-0.781 million years ago ( link->). Scelidodon capellini seems to be thought of recently as a synonym of Catonyx tarijensis, and as far as I'm aware records for this species go as far back as ca. 1.07-0.98 million years ago ( Ramón & Boilini, 2015), which is firmly within the Ensenadan. I have recently come across a more recent publication ( Ubilla & Martínez, 2016) with data consistent with the Raigón Formation also having a Pleistocene age. This publication makes several optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) age estimates from medium and upper beds (with sandy samples). At the very least, the resulting ages are well into the Middle Pleistocene, with a few Late Pleistocene age estimates derived from the dating method. Some mammal fossils still suggest Pliocene to Middle Pleistocene age. Looking at the (approximate) stratigraphic location of the bone from Tambussi et al. (particularly Fig. 2), it's not from the top formation, but closer to the bottom (but at the same time, definitely not at the very bottom). Now, what about the last phorusrhacids ever? First, there is a distal portion of a right tarsometatarsus (MNHN-1736) from a phorusrhacid that was apparently recovered from Late Pleistocene-aged sediments in Uruguay (Dolores Formation); enamel from a proboscidean molar from the same stratigraphic level was dated to ~17,620 years ago ( Alvarenga et al., 2010). Alvarenga et al. (2010) originally claimed that dissimilarities with psilopterines and brontornithids suggest it is not either of these, but could be a phorusrhacine, patagornithine, or mesembriornithine. However, in their more recent paper presenting late Pleistocene Psilopterus sp. remains, they disagree with this assessment and note more resemblances to Procariama (which has recently been assigned to Mesembriornithinae) or Psilopterus. In any case, despite the subfamiliar uncertainties, the specimen is ultimately assigned as a clear, undetermined phorusrhacid. And then, of course, there's the young Psilopterus specimen (Jones et al., 2018). Note, however, that their age estimate of 96,040±6,300 years is a maximum estimate; it is the age at the base (read: the oldest layer) of the sediment in which they were found. Given the evidence above, it would seem clear that (psilopterine and mesembriornithine) phorusrhacids survived to the Late Pleistocene. In fact, Jones et al. (2018) note that some recent evidence for the earliest human settlements in South America (~18,500 BP) might even suggest that humans might have coexisted with these last terror birds. Although we can infer that these small taxa were not apex predatory forms given how small they were compared to the large mammalian carnivores of the ecosystem, the authors suggest that phorusrhacids, and other carnivorous birds (both predatory and scavenging), had significant trophic roles in Late Pleistocene ecosystems of South America. link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs12542-017-0388-y |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 21, 2020 8:31:33 GMT 5

Titanis remains have apparently been reported in southern California. THE TERROR BIRD, TITANIS (PHORUSRHACIDAE), FROM PLIOCENE OLLA FORMATION, ANZA-BORREGO DESERT STATE PARK®, SOUTHERN CALIFORNIACHANDLER, Robert M., JEFFERSON, George T., LINDSAY, Lowell, and VESCERA, Susan P., Colorado Desert District Stout Research Center, Borrego Springs, CA, USA During the Great American Biotic Interchange that took place after the formation of the Panamanian Land Bridge during the mid-Pliocene, Titanis walleri (family Phorusrhacidae, known as terror birds) entered southern-most North America. Specimens of the 2 m-tall, 150 kg flightless birds are known from Florida and a single specimen from the gulf coast of Texas. Unfortunately, most are postcranial remains and no premaxillae are known. The anterior-most part of a premaxilla (beak), ABDSP (LACM) 6747/V26697, from the Olla Formation, 3.7 Ma, Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, was recently re-identified as Titanis and is comparable to the South American Patagonis marshi. The specimen was previously assigned to Aiolornis incredibilis. This new identification is important for several reasons: 1. It represents a significant geographic range extension for the genus; 2. It may represent the oldest known Titanis remains from the US; and 3. It reinforces the tropical aspect of the paleoenvironment of the Pliocene Epoch ancestral Colorado River deltaic deposit within the Salton Trough, California. escholarship.org/content/qt3km3d2wm/qt3km3d2wm.pdf

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 26, 2020 7:45:30 GMT 5

Some notes on neck function in Andalgalornis. Tambussi et al. (2012)->I think the second main function of the neck muscles would also be important in that, since the skull of Andalgalornis was poorly suited to withstanding mediolateral stresses, quickly pulling the head and neck back to their original position would allow the bird to minimize post-strike contact, and therefore avoid excessive strain on its skull. Now, in the first place I doubt such a method of attacking would incur anywhere near as much unacceptable mediolateral stress as biting and grappling with the prey item would, but I still think that this would, if anything, further allow the terror bird to avoid structural damage to its skull. Here's another interesting observation noted in this paper, and the functional implication thereof.

Unrelated: the muscles scars on the thoracic vertebra on an indeterminate phorusrhacine were apparently quite pronounced. Degrange et al. (2019)-> |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 26, 2020 17:00:33 GMT 5

Mesembriornis' skull (D in the figure below) is vaguely bird of prey-like and very unlike the skulls of Phorusrhacos and patagornithines. That is, the beak is nowhere near as deep.  Alvarenga & Höfling (2003)-> Alvarenga & Höfling (2003)->I wonder if it was less suited for downward strikes as deep-beaked terror birds and simply bit its prey instead. On the other hand, Procariama (which I mentioned above was more recently assigned to Mesembriornithinae) does have a skull somewhat more reminiscent of "normal" phorusrhacids, though its beak does still seem to be shallower.  Same source as above.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 28, 2020 3:04:25 GMT 5

Ungual phalanges of different phorusrhacids and Brontornis.  www.colibri.udelar.edu.uy/jspui/bitstream/20.500.12008/4112/1/uy24-14537.pdf www.colibri.udelar.edu.uy/jspui/bitstream/20.500.12008/4112/1/uy24-14537.pdfInterestingly, the digit III pedal ungual of Brontornis is, although broader than those of other phorusrhacids, very curved (contrary to what I read from one of the sources above) and in possession of a well developed flexor tubercle with pronounced lateral expansions. It is noted (in Spanish) that the similarity to the pedal unguals of gastornithids and dromornithids is actually superficial. Hmmm... |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on May 29, 2020 20:07:37 GMT 5

I don't know if anyone has ever noted this in published literature yet (although, Robert Chandler, who has found fossils of Titanis and done some work on it, apparently voiced support for the hypothesis that climate change killed off Titanis->), but perhaps in an effort to shed more light on Titanis' extinction, its last record (1.8 Ma) does correlate pretty well with the end of the Gelasian/start of the Calabrian ages ( link->), as well as the end of the Blancan NALMA; it appears that ~1.8 Ma is most commonly ascribed to the Blancan's upper boundary ( link->). At least from what I could find, there seems to have been some climate cooling going on since the Gelasian ( Pervesler et al., 2011). Mind you, there are other extinctions associated with the end of the Gelasian age and Blancan NALMA. For one, the end of the Gelasian/beginning of the Calabrian is defined by the extinction of Discoaster brouweri. Apparently, at or towards the end of the Blancan, three-toed horses, borophagine canids, and dugongs become extinct in North America ( link->), among others ( Rhynchotherium praecursor, for example, also seems to disappear at the end of the Blancan->, even though the Wikipedia page and FossilWorks page for the genus as a whole confusingly state the end of its temporal range to be 3.6 Ma). |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Oct 12, 2020 23:43:24 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Oct 16, 2020 17:49:23 GMT 5

Some bite force estimates for phorusrhacids. Degrange was one of the authors of the Andalgalornis bite force/skull mechanics paper, and this thesis seems to provide a more refined estimate. - Phorusrhacos (117 kg): 1369 N - Kelenken: 1945.55 N - Devincenzia (~160 kg): 2979.79 N - Andalgalornis (40 kg): 696.67 N (this is over 5 times harder than the 133 N estimated by Degrange et al. (2010)!!!) sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/83640 |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jan 25, 2021 6:39:59 GMT 5

|

|