Post by Infinity Blade on May 21, 2020 1:25:05 GMT 5

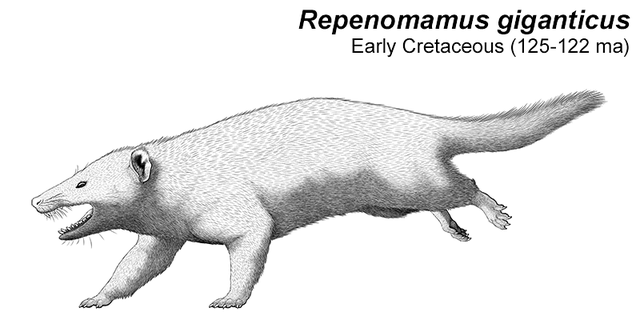

Repenomamus spp.

Image source->

Temporal range: Early Cretaceous, Aptian (~126 Ma)[1]

Scientific classification:

Life

Clade: Neomura

Domain: Eukarya

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

Clade: Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Clade: Therapsida

Clade: Neotherapsida

Clade: Theriodontia

Clade: Eutheriodontia

Clade: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicyonodontia

Clade: Eucynodontia

Clade: Probainognathia

Clade: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliformes

Class: Mammalia

Clade: Holotheria

Order: †Gobiconodonta

Family: †Gobiconodontidae

Genus: †Repenomamus

Species: †R. robustus, †R. giganticus

Repenomamus (“reptile mammal”, named for being a mammal with “reptilian” features[2]; R. robustus meaning “strong reptile mammal” for its size[2]; R. giganticus from the Greek gigantikos, again referring to its size[3]) is an extinct genus of gobiconodont mammal that lived in the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Its remains have been found in the Lujiatun Bed (the holotype of R. robustus was found in Lujiatun Village[2]) of the Yixian Formation, and the animal would have lived approximately 126 million years ago.[1]

Description and paleobiology:

R. robustus was the largest known Mesozoic mammal until the discovery of R. giganticus; these species were estimated to weigh 4-6 kg and 12-14 kg, respectively.[3]

Early mammals seem to have typically possessed sprawling legs. Recovered specimens of both species still showed sprawling hindlimbs and/or forelimbs.[4] The manus and pes was broad and plantigrade.[3] The presence or lack of hindfoot spurs and their nature may be of interest regarding Repenomamus; there is a proposal that mammals were basally venomous, possessing a platypus-like extratarsal spur consisting of an os calcaris and ossified cornu calcaris, and that this was lost in crown therians.[5] Several specimens of Repenomamus spp. are known, but so far no evidence of an os calcaris and ossified cornu calcaris has been found.[4] This would seem to suggest the lack of a spur. Even if Repenomamus had spurs, it was likely non-venomous; its fellow gobiconodontid, Gobiconodon itself, is known to have had spurs, but they lacked grooves that could act as venom canals, suggesting that it was non-venomous.[5]

Repenomamus dental formula has been most recently interpreted as 3.1.1.5/2.1.2.5., differing from its relative Gobiconodon in lacking a third lower incisor and second upper premolar.[6] The incisors were the strongest teeth in the jaw, with the canines being similar to the incisors in shape. The premolariforms had a simple shape with a pointed tip, while the molariforms had blunt crowns and decreased in size posteriorly through the jaw.[3]

The skull of the R. robustus holotype was ~101.5 mm long along the midline, with a maximum width of 71 mm (across the craniomandibular joint). Its rostrum was relatively short. The skull shares the following derived characteristics of mammals: “…well-developed dentary/squamosal articulation, differentiation of premolars and molars in postcanine teeth, presence of a dorsal process of the premaxilla that is not in contact with the nasal (exception in Sinoconodon), closed medial wall of the orbit, and presence of a fingerlike promontorium on the petrosal”. However, it also possesses some “reptilian” characteristics that non-mammalian synapsids possessed. These include a postdentary bar, the lack of an angular process in the dentary, a simple cheek tooth structure, a relatively small braincase, and a lambdoid crest and occipital plate more similar in morphology to those of non-mammalian synapsids than those of other mammals.[2]

The skull of R. giganticus was 50% longer than that of R. robustus, and likewise had a stronger sagittal crest, lambdoid crest, and zygomatic arch than that of R. robustus. The incisors were proportionately larger than the smaller species’ and less widely spaced. Also, the mandibular symphysis was proportionately deeper and the mandible was more robust altogether than in R. robustus. The denture possessed an obliquely-oriented symphysis, a broad coronoid process, and a deep masseteric fossa.[3]

With strong and pointed anterior teeth, as well as strong jaw muscles, Repenomamus seems to have been a predator. The discovery of a juvenile Psittacosaurus (about one third of its head-body length) in one specimen’s gut supports this view. This also provided the first direct evidence that some triconodont mammals hunted small vertebrates, including small dinosaurs. Repenomamus was actually larger than several dromaeosaurid taxa from the same fauna; it is thought that it could, therefore, compete with some dinosaurs for food and territory.[3]

R. giganticus with juvenile Psittacosaurus remains in its stomach. Image source->

References:

[1] Chang, S. C., Gao, K. Q., Zhou, C. F., & Jourdan, F. (2017). New chronostratigraphic constraints on the Yixian Formation with implications for the Jehol Biota. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 487, 399-406.

[2] Li, J., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., & Li, C. (2001). A new family of primitive mammal from the Mesozoic of western Liaoning, China. Chinese Science Bulletin, 46(9), 782-785.

[3] Hu, Y., Meng, J., Wang, Y., & Li, C. (2005). Large Mesozoic mammals fed on young dinosaurs. Nature, 433(7022), 149-152.

[4] Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., & Hurum, J. H. (2006). Limb posture in early mammals: sprawling or parasagittal. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 51(3).

[5] Hurum, J. H., Luo, Z. X., & Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. (2006). Were mammals originally venomous?. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 51(1).

[6] Lopatin, A., & Averianov, A. (2015). Gobiconodon (Mammalia) from the Early Cretaceous of Mongolia and revision of Gobiconodontidae. Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 22(1), 17-43.

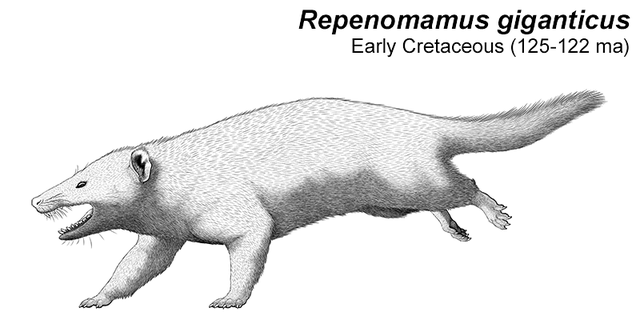

Image source->

Temporal range: Early Cretaceous, Aptian (~126 Ma)[1]

Scientific classification:

Life

Clade: Neomura

Domain: Eukarya

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

Clade: Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Clade: Therapsida

Clade: Neotherapsida

Clade: Theriodontia

Clade: Eutheriodontia

Clade: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicyonodontia

Clade: Eucynodontia

Clade: Probainognathia

Clade: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliformes

Class: Mammalia

Clade: Holotheria

Order: †Gobiconodonta

Family: †Gobiconodontidae

Genus: †Repenomamus

Species: †R. robustus, †R. giganticus

Repenomamus (“reptile mammal”, named for being a mammal with “reptilian” features[2]; R. robustus meaning “strong reptile mammal” for its size[2]; R. giganticus from the Greek gigantikos, again referring to its size[3]) is an extinct genus of gobiconodont mammal that lived in the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Its remains have been found in the Lujiatun Bed (the holotype of R. robustus was found in Lujiatun Village[2]) of the Yixian Formation, and the animal would have lived approximately 126 million years ago.[1]

Description and paleobiology:

R. robustus was the largest known Mesozoic mammal until the discovery of R. giganticus; these species were estimated to weigh 4-6 kg and 12-14 kg, respectively.[3]

Early mammals seem to have typically possessed sprawling legs. Recovered specimens of both species still showed sprawling hindlimbs and/or forelimbs.[4] The manus and pes was broad and plantigrade.[3] The presence or lack of hindfoot spurs and their nature may be of interest regarding Repenomamus; there is a proposal that mammals were basally venomous, possessing a platypus-like extratarsal spur consisting of an os calcaris and ossified cornu calcaris, and that this was lost in crown therians.[5] Several specimens of Repenomamus spp. are known, but so far no evidence of an os calcaris and ossified cornu calcaris has been found.[4] This would seem to suggest the lack of a spur. Even if Repenomamus had spurs, it was likely non-venomous; its fellow gobiconodontid, Gobiconodon itself, is known to have had spurs, but they lacked grooves that could act as venom canals, suggesting that it was non-venomous.[5]

Repenomamus dental formula has been most recently interpreted as 3.1.1.5/2.1.2.5., differing from its relative Gobiconodon in lacking a third lower incisor and second upper premolar.[6] The incisors were the strongest teeth in the jaw, with the canines being similar to the incisors in shape. The premolariforms had a simple shape with a pointed tip, while the molariforms had blunt crowns and decreased in size posteriorly through the jaw.[3]

The skull of the R. robustus holotype was ~101.5 mm long along the midline, with a maximum width of 71 mm (across the craniomandibular joint). Its rostrum was relatively short. The skull shares the following derived characteristics of mammals: “…well-developed dentary/squamosal articulation, differentiation of premolars and molars in postcanine teeth, presence of a dorsal process of the premaxilla that is not in contact with the nasal (exception in Sinoconodon), closed medial wall of the orbit, and presence of a fingerlike promontorium on the petrosal”. However, it also possesses some “reptilian” characteristics that non-mammalian synapsids possessed. These include a postdentary bar, the lack of an angular process in the dentary, a simple cheek tooth structure, a relatively small braincase, and a lambdoid crest and occipital plate more similar in morphology to those of non-mammalian synapsids than those of other mammals.[2]

The skull of R. giganticus was 50% longer than that of R. robustus, and likewise had a stronger sagittal crest, lambdoid crest, and zygomatic arch than that of R. robustus. The incisors were proportionately larger than the smaller species’ and less widely spaced. Also, the mandibular symphysis was proportionately deeper and the mandible was more robust altogether than in R. robustus. The denture possessed an obliquely-oriented symphysis, a broad coronoid process, and a deep masseteric fossa.[3]

With strong and pointed anterior teeth, as well as strong jaw muscles, Repenomamus seems to have been a predator. The discovery of a juvenile Psittacosaurus (about one third of its head-body length) in one specimen’s gut supports this view. This also provided the first direct evidence that some triconodont mammals hunted small vertebrates, including small dinosaurs. Repenomamus was actually larger than several dromaeosaurid taxa from the same fauna; it is thought that it could, therefore, compete with some dinosaurs for food and territory.[3]

R. giganticus with juvenile Psittacosaurus remains in its stomach. Image source->

References:

[1] Chang, S. C., Gao, K. Q., Zhou, C. F., & Jourdan, F. (2017). New chronostratigraphic constraints on the Yixian Formation with implications for the Jehol Biota. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 487, 399-406.

[2] Li, J., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., & Li, C. (2001). A new family of primitive mammal from the Mesozoic of western Liaoning, China. Chinese Science Bulletin, 46(9), 782-785.

[3] Hu, Y., Meng, J., Wang, Y., & Li, C. (2005). Large Mesozoic mammals fed on young dinosaurs. Nature, 433(7022), 149-152.

[4] Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., & Hurum, J. H. (2006). Limb posture in early mammals: sprawling or parasagittal. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 51(3).

[5] Hurum, J. H., Luo, Z. X., & Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. (2006). Were mammals originally venomous?. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 51(1).

[6] Lopatin, A., & Averianov, A. (2015). Gobiconodon (Mammalia) from the Early Cretaceous of Mongolia and revision of Gobiconodontidae. Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 22(1), 17-43.