|

|

Post by Life on Feb 8, 2021 21:26:24 GMT 5

The Basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus):max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1016321034-4e93d0dc223b48f4a9df61984730eb8e.jpg) George Karbus Photography / Getty Images Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia | | Phylum | Chordata | | Subphylum | Vertebrata | Class

| Chondrichthyes

| | Order | Lamniformes | | Family | Cetorhinidae | | Genus | Cetorhinus | Species

| Cetorhinus maximus

| Niche

| Planktivore; non-insect arthropods

| Habitat and maximum depth

| Pelagic; Epipelagic; ~2000 m (6561.68 ft) maximum stated depth

| Temperature tolerance range

| 8 - 14°C

|

---

General references

---

Overview from Animal Fact Files

----- Physiology and anatomy---

Recorded sizes

From McClain et al (2015) for reference:

Citation: McClain, C. R., Balk, M. A., Benfield, M. C., Branch, T. A., Chen, C., Cosgrove, J., ... & Thaler, A. D. (2015). Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna. PeerJ, 3, e715. ---

Sensory system and prey detection From Kempster and Collin (2011) for reference:

Citation: Kempster, R. M., & Collin, S. P. (2011). Electrosensory pore distribution and feeding in the basking shark Cetorhinus maximus (Lamniformes: Cetorhinidae). Aquatic Biology, 12(1), 33-36.

-----

Feeding strategy ---

Picture: Shane Stigant. Description: This basking shark is feeding on planktonic shrimp. The camera flash reflects off tiny particles such as plankton and shows them as little flecks in the water. Niarbyl, Isle of Man 2003. ---[1]

Picture: Marine Conservation Society.

Description: The huge basking shark feeds on zooplankton such as these planktonic shrimp. These are photographed through a microscope, magnified about 15 times bigger than real life. They are actually about half the size of an uncooked rice grain. ---[1]

---

Description: This type of feeding is called obligate ram filter-feeding. The other large filter-feeding sharks, the whale shark (Rhincodon typus) and the megamouth shark (Megachasma pelagios) feed by a different method, suction-feeding. This means that they don’t have to swim forward fast through their prey in the same way as the ram-feeding basking sharks. ---[1] ----- Up-close swimming and diving experiences--- 2021 ---

Credit: Storyful Viral

--- 2020 ---

Credit: IG/ tom __gillespie via Storyful --- 2019 --- Credit: TheGamingBeaver --- 2018 --- Credit: MrandMrsBucketList.com

--- 2017 ---

|

|

|

|

Post by Life on Feb 8, 2021 22:36:56 GMT 5

Plankton Can Run, But Can't Hide From Basking Sharks Basking sharks are much more canny predators than previously thought, ecologists have discovered. According to new research published online by the British Ecological Society's Journal of Animal Ecology, basking sharks are able to reverse their normal pattern of diving at dawn and surfacing at dusk in order to foil the attempts of zooplankton trying to evade capture. As well as shedding new light on basking behaviour, the results have important implications for the conservation of shark species.

Dr David Sims of the Marine Biological Association and colleagues examined diving behaviour of four basking sharks (Cetorhinus maximus) - two in the shallow sea off Plymouth and two in the deep water off the shelf-edge southwest of Ireland and in northern Clyde Sea in Scotland - using pop-up tags that measure swimming depth, water temperature and light levels. The tags were programmed to detach themselves from the sharks at a set time, float to the surface and then drift with the currents like a "electronic messages in bottles", before being washed up on beaches and found by the public.

Sims found that while the sharks in deep waters exhibited normal diving behaviour, tracking the zooplankton Calanus up to the surface at dusk and then downward at dawn, sharks in the western English Channel did the reverse. This is the first time this behaviour has been observed among plankton-eating sharks, the authors say, and shows that shark diving behaviour differs predictably between deep waters and in shallow seas close to plankton-rich boundaries in water temperature.

Although the mechanisms underlying this behaviour are unclear, the results indicate that the sharks are responding to changes in vertical migration by the zooplankton. Zooplankton have evolved a range of behaviours to try and avoid being eaten, sometimes staying at greater depths during the day and then feeding near the surface at night but at other times reversing this behaviour in an attempt to throw some of their predators (eg fish larvae and predatory invertebrates such as arrow worms) off their trail. However, this study shows that basking sharks seem to have rumbled them.

As well as shedding new light on behavioural strategies of plankton-feeding sharks and whales, the results have important implications for methods used to monitor populations of basking sharks and other species. "There is concern that the world's two largest fish species, the whale shark Rhincodon typus and the basking shark, have low population levels as a result of human exploitation. Data on population sizes for these species are lacking, and diving behaviour is one factor contributing to surveying bias," the authors say. Unless adjusted to account for these differences in diving patterns, current surveys could be over- or underestimating basking shark abundance by at least 10-fold.

Up to 10 metres long and weighing up to 7 tons - about the size of double-decker bus - the basking shark is the world's second largest fish and feeds by filtering plankton from sea water through its enormous mouth. It is able to filter up to 2,000 tons of water per hour - the equivalent of an Olympic-sized swimming pool. It is harmless to humans, but has been netted and harpooned for its oil which was burned in lamps and more recently for its fins. ----- Research article: Habitat‐specific normal and reverse diel vertical migration in the plankton‐feeding basking shark Summary

1. Megaplanktivores such as filter‐feeding sharks and baleen whales are at the apex of a short food chain (phytoplankton–zooplankton–vertebrate) and are sensitive indicators of sea‐surface plankton availability. Even though they spend the majority of their time below the surface it is still not known how most of these species utilize vertical habitat and adapt to short‐term changes in food availability.

2. A key factor likely to control vertical habitat selection by planktivorous sharks is the diel vertical migration (DVM) of zooplankton; however, no study has determined whether specific ocean‐habitat type influences their behavioural strategy. Based on the first high‐resolution dive data collected for a plankton‐feeding fish species we show that DVM patterns of the basking shark Cetorhinus maximus reflect habitat type and zooplankton behaviour.

3. In deep, well‐stratified waters sharks exhibited normal DVM (dusk ascent–dawn descent) by tracking migrating sound‐scattering layers characterized by Calanus and euphausiids. Sharks occupying shallow, inner‐shelf areas near thermal fronts conducted reverse DVM (dusk descent–dawn ascent) possibly due to zooplankton predator–prey interactions that resulted in reverse DVM of Calanus.

4. These opposite DVM patterns resulted in the probability of daytime‐surface sighting differing between these habitats by as much as two orders of magnitude. Ship‐borne surveys undertaken at the same time as trackings reflected these behavioural differences.

5. The tendency of basking sharks to feed or rest for long periods at the surface has made them vulnerable to harpoon fisheries. Ship‐borne and aerial surveys also use surface occurrence to assess distribution and abundance for conservation purposes. Our study indicates that without bias reduction for habitat‐specific DVM patterns, current surveys could under‐ or overestimate shark abundance by at least 10‐fold. Citation: Sims, D. W., Southall, E. J., Tarling, G. A., & Metcalfe, J. D. (2005). Habitat‐specific normal and reverse diel vertical migration in the plankton‐feeding basking shark. Journal of Animal Ecology, 74(4), 755-761.

|

|

|

|

Post by Life on Feb 8, 2021 22:50:11 GMT 5

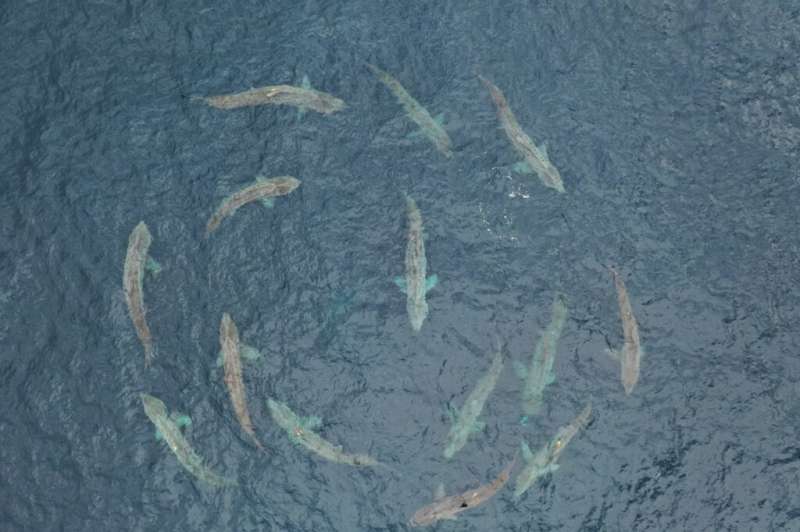

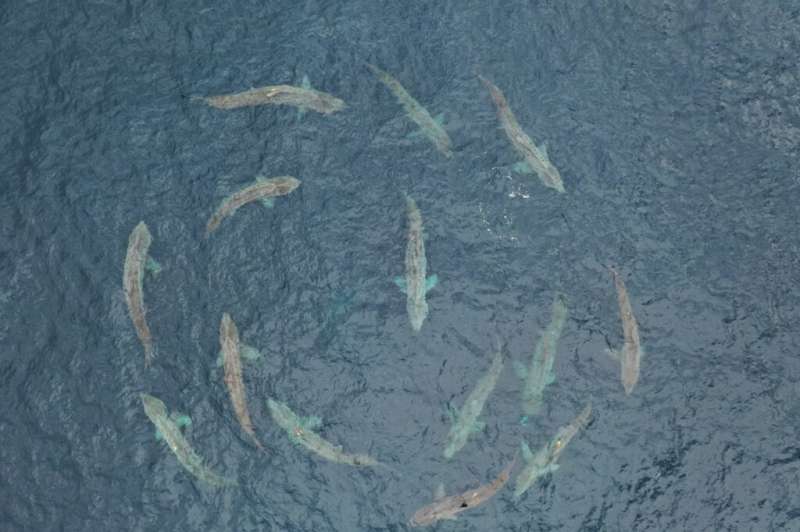

Basking sharks gather in large groups off northeast US coastGroup sightings are fairly rare Groups of basking sharks ranging from as few as 30 to nearly 1,400 individual animals have been observed aggregating in waters from Nova Scotia to Long Island. While individual sightings are fairly common, seeing large groups is not.The reason why the animals congregate has not been clearly determined, although it is thought to be related to feeding, socializing, and/or courtship given behaviors in other shark species. In a recent study reported in the Journal of Fish Biology, researchers analyzed aggregations of basking sharks ( Cetorhinus maximus) recorded off the northeastern United States coast to learn more about the phenomenon. Observations of these aggregation events are relatively rare. In almost 40 years of aerial surveys for right whales, ten large basking shark aggregation events were opportunistically recorded and photographed. Comparing this information with that collected in a number of earth-orbiting satellite and oceanographic databases and by the NEFSC's ecosystem monitoring (EcoMon) cruises in the same region, researchers obtained more insight into this behavior. "Aerial surveys provide a valuable perspective on aggregations and their potential functions, especially when coupled with environmental satellite and ship-based survey data," said Leah Crowe, a protected species researcher at NOAA's Northeast Fisheries Science Center and lead author of the study. The researchers found the aggregations occurred in summer and fall when sea surface temperatures ranged between 55 and 75 degrees F (13 to 24 degrees C). In the largest event, data were available to indicate there was a high concentration of zooplankton prey present. Largest aggregation sighted had 1,400 animalsTen large aggregations of basking sharks were identified between June 1980 and November 2013, ranging from 36 to at least 1,398 animals within an 11.5-mile (18.5-kilometer) radius of the central point in the aggregation. Data on breaching, circular swimming movements, and/or apparent feeding behavior were recorded in seven of the ten largest aggregations. The largest aggregation ever recorded on the aerial survey was at least 1,398 animals photographed on November 5, 2013 in southern New England waters. As luck would have it, the NEFSC's EcoMon survey sampled the same area on November 16 and 17, 2013, providing an estimate of the zooplankton community characteristics in that area at that time of year. "Photogrammetry, the use of photographs to measure objects, has provided estimated lengths of animals at the surface and allowed us to classify animals in the aggregation as likely juveniles or mature adults," said Crowe, who works at the NEFSC's Woods Hole Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass. Given the apparent presence of juveniles and an abundance of zooplankton on the continental shelf at the time of the event, the study authors say it is likely foraging played a role in the formation of that aggregation. The study also suggests that the animals may be aggregating to draft off each other for more efficient feeding given the immense drag from having their mouths open. Basking Sharks are Second Largest FishBasking sharks are the world's second largest fish, growing as long as 32 feet and weighing more than five tons. They are highly migratory, slow-moving animals often sighted close to the surface with their large mouths open to filter zooplankton from seawater. They are considered passive and no danger to humans other than that posed by their large size and rough skin. They and the larger whale shark, along with the megamouth shark, are the three shark species that eat plankton. Sighting surveys and environmental analyses from the study aligned with previous studies that found these large aggregations form in areas of high prey density, often along thermal fronts and in areas with high chlorophyll concentrations, perhaps exploiting spring and fall zooplankton blooms prior to the animals' seasonal migration out of the region. Data also confirm that basking sharks prefer waters between 55 and 68 degrees F (13 to 20 degrees C). While these aggregations may provide the opportunity for socializing, courtship, and mating, some behaviors suggest they are not solely related to courtship as proposed in previous studies. The reproductive cycle of basking sharks is not well understood, and questions remain about why the animals gather in large groups and how they interact with each other when in them. "Although the reason for these aggregations remains elusive, our ability to access a variety of survey data though the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium Database and to compare information has provided new insight into the potential biological function of these rare events," Crowe said. "The study also highlights the value of opportunistic data collection."Link: www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/03/180330105757.htm-----

Research article: Characterization of large basking shark Cetorhinus maximus aggregations in the western North Atlantic Ocean

Abstract

Cetorhinus maximus aggregations recorded during extensive aerial survey efforts off the north‐eastern United States between 1980 and 2013 included aggregations centring on sightings with group sizes of at least 30 individuals. These aggregations occurred in summer and autumn months and included aggregation sizes of up to 1398 individuals, the largest aggregation ever reported for this species. The aggregations were associated with sea surface temperatures of 13–24° C and chlorophyll‐a concentrations of 0·4–2·6 mg m−3 and during one aggregation, a high abundance of zooplankton prey was present. Photogrammetric tools allowed for the estimation of total body lengths ranging between 4 and 8 m. Characterization of these events provides new insight into the potential biological function of large aggregations in this species.

Citation: Crowe, L. M., O'brien, O., Curtis, T. H., Leiter, S. M., Kenney, R. D., Duley, P., & Kraus, S. D. (2018). Characterization of large basking shark Cetorhinus maximus aggregations in the western North Atlantic Ocean. Journal of fish biology, 92(5), 1371-1384.

|

|

|

|

Post by Life on Feb 8, 2021 23:01:08 GMT 5

Basking sharks can jump as high and as fast as great whitesThe second-largest fish in the world can swim more than twice as fast as the average man in the Olympic 50m freestyle A collaborative team of marine biologists has discovered that basking sharks, hundreds of which are found off the shores of Ireland, Cornwall, the Isle of Man and Scotland, can jump as fast and as high out of the water as their cousins, the famously powerful and predatory great white shark.Basking sharks are the second largest fish in the world, reaching lengths of up to 10m (33ft). Until now, they have previously had a reputation for being slow and languid as they scour the sea for their staple diet of plankton. However, a new study, recently published in leading international journal Biology Letters used video analysis for both species and estimated their vertical swimming speeds at the moment at which they left the water. Furthermore, they attached a data recording device to one large basking shark to measure its speed and movement, and also to store video footage. At one point, in just over nine seconds, and with 10 beats of its tail, the basking shark accelerated from a depth of 28 m to the surface and broke through the water at nearly 90 degrees. The shark cleared the water for one second, and its leap peaked at a height of 1.2 m above the surface. To achieve this breach, the basking shark exhibited a six-fold increase in tail beat frequency and attained a top speed of approximately 5.1 m/s. To put this into perspective, this is more than twice as fast as the average competitor in the Olympic men's 50m freestyle swim. The videos from boats and the land of both basking sharks and great whites breaching showed similar speeds of breaching in other individuals. The basking shark videos were recorded in 2015 at Malin Head, Ireland, while the great white shark videos were recorded in 2009 at two sites in South Africa, where seal-shaped decoys induced feeding attempts. Assistant Professor in Zoology at Trinity College Dublin, Dr Nick Payne, was a co-author of the journal article. He said: "The impressive turn of speed that we found basking sharks exhibit shows how much we are yet to learn about marine animals -- even the largest, most conspicuous species have surprises in store, if we're willing to look."Dr Jonathan Houghton, Senior Lecturer in Marine Biology at Queen's University Belfast, said: "This finding does not mean that basking sharks are secretly fierce predators tearing round at high speed; they are still gentle giants munching away happily on zooplankton. It simply shows there is far more to these sharks than the huge swimming sieves we are so familiar with. It's a bit like discovering cows are as fast as wolves (when you're not looking)."Link: www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/09/180920102105.htm-----

Research article: Latent power of basking sharks revealed by exceptional breaching eventsAbstract The fast swimming and associated breaching behaviour of endothermic mackerel sharks is well suited to the capture of agile prey. In contrast, the observed but rarely documented breaching capability of basking sharks is incongruous to their famously languid lifestyle as filter-feeding planktivores. Indeed, by analysing video footage and an animal-instrumented data logger, we found that basking sharks exhibit the same vertical velocity (approx. 5 m s−1) during breach events as the famously powerful predatory great white shark. We estimate that an 8-m, 2700-kg basking shark, recorded breaching at 5 m s−1 and accelerating at 0.4 m s−2, expended mechanical energy at a rate of 5.5 W kg−1; a mass-specific energetic cost comparable to that of the great white shark. The energy cost of such a breach is equivalent to around 1/17th of the daily standard metabolic cost for a basking shark, while the ratio is about half this for a great white shark. While breaches by basking sharks must serve a different function to white shark breaches, their similar breaching speeds questions our perception of the physiology of large filter-feeding fish. Citation: Johnston, E. M., Halsey, L. G., Payne, N. L., Kock, A. A., Iosilevskii, G., Whelan, B., & Houghton, J. D. (2018). Latent power of basking sharks revealed by exceptional breaching events. Biology letters, 14(9), 20180537.

---

Figure 1 from Johnston et al (2018) for reference:

Figure 1. Comparing basking (left panel) and white (right panel) sharks. (a) The external morphology of these species is similar; (b) breaches by these species; (c) vertical breach velocity as determined from video analysis; means and one standard deviation. Illustrations reproduced with permission of Marc Dando, and breaching images credited to Bren Whelan and White Shark Africa™. (Online version in colour.) ---

|

|

|

|

Post by Life on Jan 13, 2023 15:44:34 GMT 5

Mysterious circling behavior of basking sharks explained Rarely observed circling behaviors of endangered basking sharks have now been explained as "shark speed dating" courtship displays, thanks to a new study. Marine biologists from the Marine Biological Association (MBA), the Irish Basking Shark Group and colleagues have led ground-breaking research which reveals the circles of basking sharks seen off western Ireland are engaged in annual reproductive behavior, the first place in the world where this has been verified. Circling formations have been documented on a few occasions over the past 40 years in the north-west Atlantic off Canada and the U.S. Although basking sharks are often seen filter-feeding plankton in U.K. and Irish coastal waters in the summer, the circling formations were rarely seen, and until now, scientists could not explain the behavior. Scientists captured footage of 19 circling groups using underwater cameras and aerial drones off County Clare, Ireland, from 2016 to 2021. They found each group comprised between six and 23 sharks swimming slowly at the surface, with others below them deeper down, in a three dimensional ring structure the researchers termed a "torus." The team found that the sharks in circle formations were equal numbers of sexually mature male and females and were not filter-feeding. Some females had a paler body color than males, a difference seen during courtship and mating behavior in other shark species. The study also showed that despite courtship torus duration lasting several hours, and perhaps even several days, individual females and males associated with most other members within a few minutes. In that time, the sharks interacted through gentle fin-fin and fin-body touching, rolling to expose ventral surfaces to following sharks, and breaching behavior perhaps as a signal of their readiness to mate. Professor David Sims, Senior Research Fellow at the MBA and University of Southampton who was lead author of the study said, "How usually solitary basking sharks find a mate in the ocean's expanse has been an enduring mystery. Incredibly we now find that a courtship torus not only forms but acts like a slow motion 'speed-dating' event for assessing lots of potential mates in one go." "It is astonishing that this wonder of the natural world has remained hidden for so long, presumably because circles most often form at depth away from surface observation, which could explain why mating itself has never been seen." Basking sharks are slow-moving ocean giants which can grow up to 12 meters in length and feed on microscopic animals called zooplankton. Throughout much the 20th Century in the north-east Atlantic they were hunted for liver oil and fins which dramatically reduced population numbers. Basking sharks remain endangered in Europe as populations continue to recover. Dr. Simon Berrow of the Irish Basking Shark Group and Atlantic Technological University, Galway who co-led the field research said, "Our discovery of important basking shark courtship grounds in coastal waters off western Ireland makes it even more urgent that this species gains protection in Irish waters from potential threats, such as from collisions with marine traffic and the impact of offshore renewables." Despite protection in many parts of the world, legislation to protect basking sharks in Irish waters was only drafted this year. If signed into law it will be illegal to hunt, injure, interfere with or destroy their breeding or resting places. The study is published in Journal of Fish Biology. The research team hope their findings can inform identification of other basking shark courtship grounds in the U.K. and further afield in the Mediterranean Sea and Pacific Ocean to ensure appropriate conservation measures are put in place to safeguard this gentle giant's "love dance." ----- Research article: Circles in the sea: annual courtship “torus” behaviour of basking sharks Cetorhinus maximus identified in the eastern North Atlantic OceanAbstractGroups of basking sharks engaged in circling behaviour are rarely observed, and their function remains enigmatic in the absence of detailed observations. Here, underwater and aerial video recordings of multiple circling groups of basking sharks during late summer (August and September 2016–2021) in the eastern North Atlantic Ocean showed groups numbering between 6 and 23 non-feeding individuals of both sexes. Sharks swam slowly in a rotating “torus” (diameter range: 17–39 m), with individuals layered vertically from the surface to a maximum depth of 16 m. Within a torus, sharks engaged in close-following, echelon, close-flank approach or parallel-swimming behaviours. Measured shark total body lengths were 5.4–9.5 m (mean L T: 7.3 m ± 0.9 s.d.; median: 7.2 m, n = 27), overlapping known lengths of sexually mature males and females. Males possessed large claspers with abrasions that were also observed on female pectoral fins. Female body colouration was paler than that of males, similar to colour changes observed during courtship and mating in other shark species. Individuals associated with most other members rapidly (within minutes), indicating toroidal behaviours facilitate multiple interactions. Sharks interacted through fin–fin and fin–body contacts, rolling to expose the ventral surfaces to following sharks, and breaching behaviour. Toruses formed in late summer when feeding aggregations in zooplankton-rich thermal fronts switched to non-feeding following and circling behaviours. Collectively, the observations explain a courtship function for toruses. This study highlights northeast Atlantic coastal waters as a critical habitat supporting courtship reproductive behaviour of endangered basking sharks, the first such habitat identified for this species globally. Citation: Sims, D. W., Berrow, S. D., O'Sullivan, K. M., Pfeiffer, N. J., Collins, R., Smith, K. L., ... & Southall, E. J. (2022). Circles in the sea: annual courtship “torus” behaviour of basking sharks Cetorhinus maximus identified in the eastern North Atlantic Ocean. Journal of Fish Biology, 101(5), 1160-1181.Full article access: onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jfb.15187

|

|

|

|

Post by Creodont on May 2, 2023 7:43:13 GMT 5

Basking Sharks gathering is one of the world's incredible nature spectacles. Hundreds of these huge plankton-eating sharks gathered on the west coast of Ireland a few years ago and created several circles usually grouped into 15 to 20 sharks and continued to gently swim in this orchestrated, circular motion for hours and days. Sometimes they regroup and spread to different groups. Some scientists think it's a mating and courting behavior but It's hard to be certain as we know very little about these prehistoric animals. |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jul 22, 2023 4:46:29 GMT 5

|

|

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1016321034-4e93d0dc223b48f4a9df61984730eb8e.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1016321034-4e93d0dc223b48f4a9df61984730eb8e.jpg)