Post by Infinity Blade on Mar 18, 2021 9:23:29 GMT 5

Peloneustes philarchus

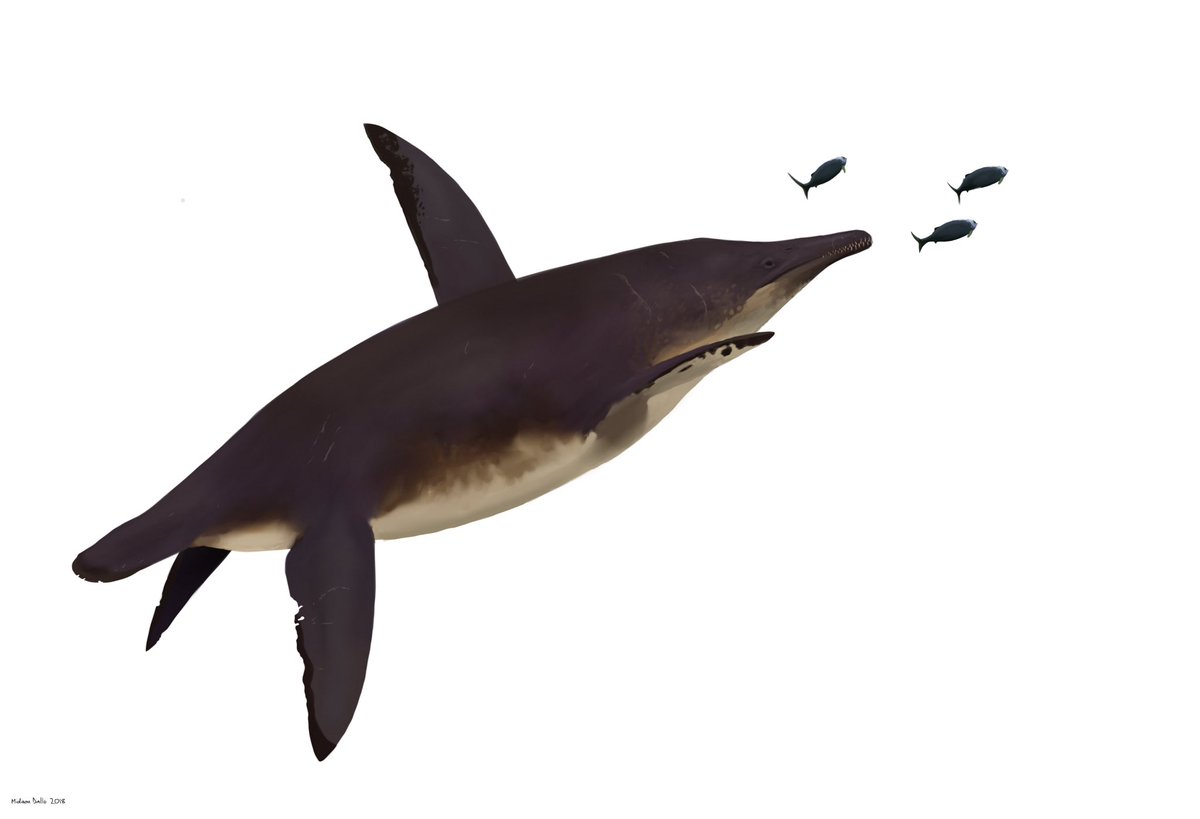

Life restoration of Peloneustes philarchus hunting fish. © @ Midiaou Diallo

Temporal range: Middle Jurassic; Callovian[1] (166.1-163.5 Ma[2])

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Clade: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Reptilia

Clade: Eureptilia

Clade: Romeriida

Clade: Diapsida

Clade: Neodiapsida

Clade: Sauria

Superorder: †Sauropterygia

Clade: †Eosauropterygia

Clade: †Pistosauroidea

Clade: †Pistosauria

Order: †Plesiosauria

Suborder: †Pliosauroidea

Family: †Pliosauridae

Clade: †Thalassophonea

Genus: †Peloneustes

Species: †P. philarchus

Peloneustes is a genus of pliosaurid[3] plesiosaur that lived in the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of the United Kingdom. Its fossils have been found in the Peterborough Member of the Oxford Clay Formation.[3]

Classification:

Peloneustes appears to currently be classified as a pliosaurid. Within Pliosauridae is a clade known as Thalassophonea, which Peloneustes is a member of. It has been recovered more than once as a basal member of the Thalassophonea.[4][5]

Description:

Mounted skeleton of Peloneustes at the Museum of Paleontology, Tübingen. © @ user theropod.

As with other pliosaurs, the head was relatively large and the neck was short. The specimen mounted in the Natural History Museum in London was described to have a total body length of 3.5 meters (11 feet, 6 inches).[6] The specimen mounted in the Museum of Paleontology, Tübingen measured 4.05 meters in length.[7] The fore flippers were smaller than the hind flippers. The teeth were slender and sharp at the tip with a circular cross section, distal recurve, and fine longitudinal ridges that sometimes reached the apex of the tooth.[3][7]

Like all plesiosaurs, Peloneustes was a fully aquatic animal with four flippers used for locomotion underwater, which allowed for efficient and effective locomotion.[8]

Two images of the skull of Peloneustes (one photograph, one illustrated reconstruction). Image sources are the Plesiosaur Directory and Slate Weasel, respectively.

Paleobiology and paleoecology:

The skull of Peloneustes was elongated and not particularly tall. Its eye sockets were kidney-shaped and elongated. Its dentition was well spaced, narrow-based, and elongated with damage being rare (when present, it was wear on the tips of the teeth). Leslie Noè noted that this cranial and dental morphology was similar to that seen in piscivorous crocodilians and river dolphins, concluding that Peloneustes was primarily a piscivore. Although he did not rule out the presence of salt-secreting glands, he proposed that it would have had less of a need for these than the cephalopod specialist Simolestes, as Peloneustes was primarily feeding on vertebrate prey.[9 (video)] The differences in skull and dental morphology from the other pliosaurids of the Peterborough Member might be interpreted as evidence of niche partitioning between the different species to avoid competition.

However, while Peloneustes might have preferred preying upon fish, evidence suggests that it was not limited to these prey items and could hunt larger, more formidable prey as well. A pectoral girdle from a specimen of Cryptoclidus eurymerus shows evidence of healed bite marks from a predator. The damage from this bite was severe enough to render the flipper functionless. The size and shape of the bite marks are suggestive of an attack by a pliosaur, possibly Peloneustes. Although a large crocodilian has also been considered as a potential culprit, such an animal is still currently unknown from the Peterborough Member.[10]

Peloneustes is the most abundant pliosauroid of the Peterborough Member.[3]

References:

[1] paleobiodb.org/classic/basicTaxonInfo?taxon_no=100090

[2] stratigraphy.org/ICSchart/ChronostratChart2020-03.pdf

[3] Ketchum, Hilary & BENSON, ROGER. (2011). The cranial anatomy and taxonomy of Peloneustes philarchus (Sauropterygia, Pliosauridae) from the Peterborough Member (Callovian, Middle Jurassic) of the United Kingdom. Palaeontology. 54. 639 - 665. 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01050.x.

[4] Benson RB, Druckenmiller PS. Faunal turnover of marine tetrapods during the Jurassic-Cretaceous transition. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2014 Feb;89(1):1-23. doi: 10.1111/brv.12038. Epub 2013 Apr 13. PMID: 23581455.

[5] Fischer V, Benson RBJ, Zverkov NG, Soul LC, Arkhangelsky MS, Lambert O, Stenshin IM, Uspensky GN, Druckenmiller PS. Plasticity and Convergence in the Evolution of Short-Necked Plesiosaurs. Curr Biol. 2017 Jun 5;27(11):1667-1676.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.052. Epub 2017 May 25. PMID: 28552354.

[6] Andrews, C. (1910). IV.—Note on a Mounted Skeleton of a Small Pliosaur, Peloneustes Philarchus, Seeley, sp. Geological Magazine, 7(3), 110-112. doi:10.1017/S0016756800132960

[7] Linder, H. (1913) Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Plesiosaurier-Gattungen Peloneustes und Pliosaurus, Nebst Anhang: Über die beiden ersten Halswirbel der Plesiosaurier. Geologische und Paläontologische Abhandlungen, 11, 339–409.

[8] Muscutt Luke E., Dyke Gareth, Weymouth Gabriel D., Naish Darren, Palmer Colin and Ganapathisubramani Bharathram 2017. The four-flipper swimming method of plesiosaurs enabled efficient and effective locomotion. Proc. R. Soc. B. 284 2017095120170951

doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.0951

[9] Noe, L.F. (2004). The evidence and implications of an invertebrate diet in Jurassic pliosaurs (Reptilia: Sauropterygia). Palaeontological Association Newsletter, 57(48th Annual Meeting Abstracts): 127. Recorded presentation of the abstract available->.

[10] Rothschild, Bruce M., Clark, Neil D.L., and Clark, Clare M. 2018. Evidence for survival in a Middle Jurassic plesiosaur with a humeral pathology: What can we infer of plesiosaur behaviour? Palaeontologia Electronica 21.1.13A 1-11. doi.org/10.26879/719 palaeo-electronica.org/content/2018/2182-plesiosaur-humeral-pathology

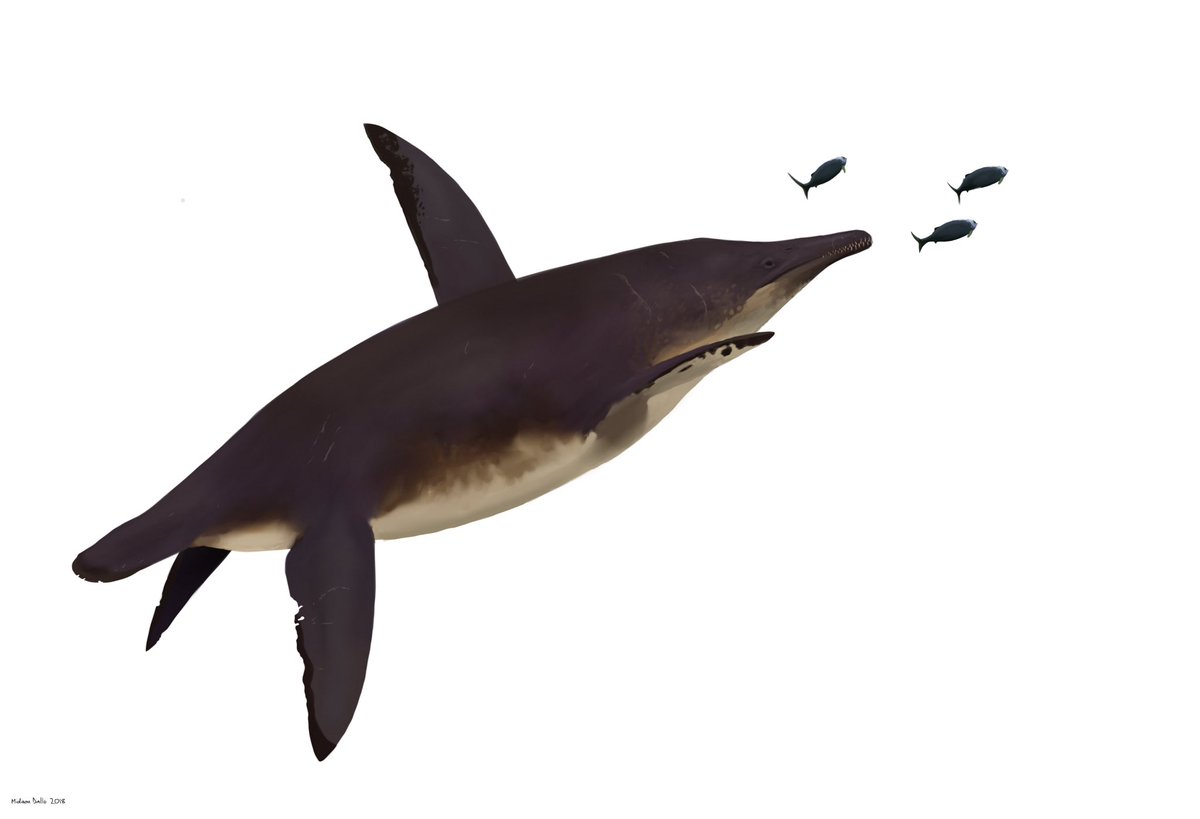

Life restoration of Peloneustes philarchus hunting fish. © @ Midiaou Diallo

Temporal range: Middle Jurassic; Callovian[1] (166.1-163.5 Ma[2])

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Clade: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Reptilia

Clade: Eureptilia

Clade: Romeriida

Clade: Diapsida

Clade: Neodiapsida

Clade: Sauria

Superorder: †Sauropterygia

Clade: †Eosauropterygia

Clade: †Pistosauroidea

Clade: †Pistosauria

Order: †Plesiosauria

Suborder: †Pliosauroidea

Family: †Pliosauridae

Clade: †Thalassophonea

Genus: †Peloneustes

Species: †P. philarchus

Peloneustes is a genus of pliosaurid[3] plesiosaur that lived in the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of the United Kingdom. Its fossils have been found in the Peterborough Member of the Oxford Clay Formation.[3]

Classification:

Peloneustes appears to currently be classified as a pliosaurid. Within Pliosauridae is a clade known as Thalassophonea, which Peloneustes is a member of. It has been recovered more than once as a basal member of the Thalassophonea.[4][5]

Description:

Mounted skeleton of Peloneustes at the Museum of Paleontology, Tübingen. © @ user theropod.

As with other pliosaurs, the head was relatively large and the neck was short. The specimen mounted in the Natural History Museum in London was described to have a total body length of 3.5 meters (11 feet, 6 inches).[6] The specimen mounted in the Museum of Paleontology, Tübingen measured 4.05 meters in length.[7] The fore flippers were smaller than the hind flippers. The teeth were slender and sharp at the tip with a circular cross section, distal recurve, and fine longitudinal ridges that sometimes reached the apex of the tooth.[3][7]

Like all plesiosaurs, Peloneustes was a fully aquatic animal with four flippers used for locomotion underwater, which allowed for efficient and effective locomotion.[8]

Two images of the skull of Peloneustes (one photograph, one illustrated reconstruction). Image sources are the Plesiosaur Directory and Slate Weasel, respectively.

Paleobiology and paleoecology:

The skull of Peloneustes was elongated and not particularly tall. Its eye sockets were kidney-shaped and elongated. Its dentition was well spaced, narrow-based, and elongated with damage being rare (when present, it was wear on the tips of the teeth). Leslie Noè noted that this cranial and dental morphology was similar to that seen in piscivorous crocodilians and river dolphins, concluding that Peloneustes was primarily a piscivore. Although he did not rule out the presence of salt-secreting glands, he proposed that it would have had less of a need for these than the cephalopod specialist Simolestes, as Peloneustes was primarily feeding on vertebrate prey.[9 (video)] The differences in skull and dental morphology from the other pliosaurids of the Peterborough Member might be interpreted as evidence of niche partitioning between the different species to avoid competition.

However, while Peloneustes might have preferred preying upon fish, evidence suggests that it was not limited to these prey items and could hunt larger, more formidable prey as well. A pectoral girdle from a specimen of Cryptoclidus eurymerus shows evidence of healed bite marks from a predator. The damage from this bite was severe enough to render the flipper functionless. The size and shape of the bite marks are suggestive of an attack by a pliosaur, possibly Peloneustes. Although a large crocodilian has also been considered as a potential culprit, such an animal is still currently unknown from the Peterborough Member.[10]

Peloneustes is the most abundant pliosauroid of the Peterborough Member.[3]

References:

[1] paleobiodb.org/classic/basicTaxonInfo?taxon_no=100090

[2] stratigraphy.org/ICSchart/ChronostratChart2020-03.pdf

[3] Ketchum, Hilary & BENSON, ROGER. (2011). The cranial anatomy and taxonomy of Peloneustes philarchus (Sauropterygia, Pliosauridae) from the Peterborough Member (Callovian, Middle Jurassic) of the United Kingdom. Palaeontology. 54. 639 - 665. 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01050.x.

[4] Benson RB, Druckenmiller PS. Faunal turnover of marine tetrapods during the Jurassic-Cretaceous transition. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2014 Feb;89(1):1-23. doi: 10.1111/brv.12038. Epub 2013 Apr 13. PMID: 23581455.

[5] Fischer V, Benson RBJ, Zverkov NG, Soul LC, Arkhangelsky MS, Lambert O, Stenshin IM, Uspensky GN, Druckenmiller PS. Plasticity and Convergence in the Evolution of Short-Necked Plesiosaurs. Curr Biol. 2017 Jun 5;27(11):1667-1676.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.052. Epub 2017 May 25. PMID: 28552354.

[6] Andrews, C. (1910). IV.—Note on a Mounted Skeleton of a Small Pliosaur, Peloneustes Philarchus, Seeley, sp. Geological Magazine, 7(3), 110-112. doi:10.1017/S0016756800132960

[7] Linder, H. (1913) Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Plesiosaurier-Gattungen Peloneustes und Pliosaurus, Nebst Anhang: Über die beiden ersten Halswirbel der Plesiosaurier. Geologische und Paläontologische Abhandlungen, 11, 339–409.

[8] Muscutt Luke E., Dyke Gareth, Weymouth Gabriel D., Naish Darren, Palmer Colin and Ganapathisubramani Bharathram 2017. The four-flipper swimming method of plesiosaurs enabled efficient and effective locomotion. Proc. R. Soc. B. 284 2017095120170951

doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.0951

[9] Noe, L.F. (2004). The evidence and implications of an invertebrate diet in Jurassic pliosaurs (Reptilia: Sauropterygia). Palaeontological Association Newsletter, 57(48th Annual Meeting Abstracts): 127. Recorded presentation of the abstract available->.

[10] Rothschild, Bruce M., Clark, Neil D.L., and Clark, Clare M. 2018. Evidence for survival in a Middle Jurassic plesiosaur with a humeral pathology: What can we infer of plesiosaur behaviour? Palaeontologia Electronica 21.1.13A 1-11. doi.org/10.26879/719 palaeo-electronica.org/content/2018/2182-plesiosaur-humeral-pathology