|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jun 24, 2021 19:24:24 GMT 5

Almost two years back, a YouTuber named Henry the PaleoGuy (a rather well known paleontology/zoology YouTuber) did a review on Walking with Dinosaurs (1999) in honor of its 20th anniversary. Well, guess what? Another dinosaur documentary is having its 20th anniversary soon (July 15th). And while I may not have a YouTube channel with a massive following nor the editing skills & resources to make a high quality video, I do have a forum I've been on for years and people I've known for a similar amount of time to share this review with. Gentlemen, I present to you my review on the Discovery Channel's When Dinosaurs Roamed America!  Image source Image sourceHere's how this is going to work. At the time of writing, it is June 24th where I am, so July 15th is three weeks from now. Given that there are five segments, I will post my reviews for the first two segments today, and one review every week until the final review & overall review are posted on the 15th, the 20th anniversary proper. I will make a separate post for the first and second segments, the former of which is down below. Below is a quick directory with each actual review hyperlinked: - Late Triassic segment (this post) - Early Jurassic segment (directly below this post) - Late Jurassic segment- Late Cretaceous segment- End Cretaceous segment- Overall verdictSo without further ado, let's get started!

Late Triassic segment – New York, 220 million years ago: Screen capture taken from When Dinosaurs Roamed America. - John Goodman explains that the Permian-Triassic extinction event was likely caused by an asteroid impact, based on available evidence…at the time. More recent evidence traces the extinction event back to volcanic CO2 emissions, particularly from the Siberian Traps (Jurikova et al., 2020; Kaiho et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021).

- I’m just going to get this out of the way: the theropods in this program tend to be depicted with pronated hands and exposed teeth. I think for the time this is forgivable. Aside from these, I don’t really have many issues with the Coelophysis model.

- Rutiodon tries to take a Coelophysis. I’m honestly not sure how suited Rutiodon was for taking down an animal this large. Coelophysis is by no means a particularly large dinosaur, but Rutiodon’s jaws are extremely longirostrine (link).

- Can I just say I really like the Coelphysis being shown as an agile, nimble animal here?

- Goodman mispronounces the aetosaur’s name as “Demastosuchus” (Desmatosuchus).

- The Rutiodon approaches a Desmatosuchus as if it were prospective prey. I’m 1,000% sure Rutiodon’s jaws are ill suited to take down a creature like this. Not only is Desmatosuchus big and robustly built, it’s armored. The Desmatosuchus duly drives off the phytosaur (and right afterwards, the Coelophysis), so I’ll give it that.

- After Coelphysis catches a locust, Goodman then goes over some of the adaptations of Coelophysis. This is the first sequence that shows the skeleton of the animal over a black background, looking into muscles and bones. It’s also one thing it does that separates it from Walking with Dinosaurs. Whether or not you care for these sequences is up to you, but I’m actually glad at least one dinosaur documentary ever did this.

- Goodman says that Coelophysis is built for speed. But while I certainly wouldn’t call it slow (I definitely think it was an agile and nimble animal), C. bauri actually did not have particularly cursorial limbs for a theropod of its size, with the lower leg being 7.6% shorter than expected for a theropod of the same femur length (Persons & Currie, 2016). Again, I can’t emphasize enough that this alone isn’t a total killer (after all, there are animals that can run surprisingly quickly without having specialized cursorial legs), so it doesn’t mean Coelophysis was a slowpoke. However, it would suggest that Coelophysis would actually be a bit slower than a similar sized theropod with more “typical” hindlimb proportions.

- Once again, an extraterrestrial impact is blamed for a major mass extinction (this time the T-J extinction event). Again, more recent evidence suggests this extinction event was more likely caused by flood basalt volcanism (Blackburn et al., 2013).

Final verdict:Out of all the sequences I remember from WDRA, the Late Triassic one is honestly the least eventful, and thus the least memorable. I honestly forgot just what the Coelophysis did here until I rewatched it. And I feel like the reason is that this segment is not presented much as a story. It’s pretty much just the Coelophysis walking, running, and jumping around, with a few brief run-ins with other animals and one scene of it hunting an insect. It would be like if you made a short where your character is seen doing random things, with no clear conflict and sequence of events, and not in a connected, plot-driven order. Yes, it’s a documentary, but it’s a documentary that’s basically trying to do what WWD did. Nevertheless, it gives the viewer with a good enough idea of what kinds of animals were roaming around at the time. And honestly, how many other times have you seen an aetosaur or phytosaur depicted in paleomedia? So overall, probably my least favorite segment in this documentary, but I guess it’s a solid start. And hey, it only gets better from here. |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jun 24, 2021 19:31:39 GMT 5

Early Jurassic segment – Pennsylvania, 200 million years ago: Image source Image source- First off, it should be noted that Pennsylvania does not actually have a lot of dinosaur remains, aside from perhaps footprints (and for that matter, New York doesn’t seem to either). Two of the three dinosaurs shown in this segment were not found in the northeastern United States. The one that was is Anchisaurus, which was found in Massachusetts and Connecticut. I think it’s possible it may have lived in what is now Pennsylvania, given its relatively close proximity to MA and CT. Dilophosaurus and “Syntarsus” kayentakatae (I call it “Syntarsus” because while Syntarsus can’t be its genus name, I was told by a friend of mine that it is neither Megapnosaurus nor Coelophysis, and needs a new genus name), on the other hand, are found in the southwestern US.

- A little nitpick: I think the dinosaurs featured here also seem to have lived a little later than 200 million years ago (except possibly Anchisaurus). Dilophosaurus and Megapnosaurus were found in the Kayenta Formation, which dates to the Sinemurian to Pliensbachian (Weishampel et al., 2004). To be fair, the Sinemurian started 199.3 Ma, but anyway, 200 Ma seems to only be approximate.

- ”Syntarsus” is apparently different from Coelophysis in that it’s a predator of dinosaurs, not insects, as if Coelophysis’ main prey were insects. We have evidence for predation on small vertebrates (Nesbitt et al., 2006) by C. bauri, which is consistent with the ziphodont teeth and clawed forelimbs. Even occasional predation on larger animals seems possible, although it was not specialized for hunting large game like many later theropods were. It is true, though, that “S.” kayentakatae had a fairly deep skull for a coelophysid. The more robust skull, coupled with larger and less numerous teeth, indeed suggest it was more specialized for larger game than its earlier relatives (Paul, 2016).

- Speaking of which, we see a group of these take on an Anchisaurus. It seems Anchisaurus is quite oversized in comparison to its assailants, though. In The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Greg Paul estimates the size of the coelophysids at 2.2 meters long and 30 kg, while his estimate for Anchisaurus is 3 meters long and 70 kg (Paul, 2016). While Anchisaurus is clearly larger, it looks too massive in comparison to the coelophysids, based on these figures.

- Also, the coelophysids are hunting the Anchisaurus during daytime. I admittedly only have news articles to go by for this information (instead of full access to a paper), but apparently a recent study found that "S." kayentakatae had effective night vision, suggesting it was nocturnal (link). This is unlike C. bauri, which, judging from measurements of its sclerotic ring, appears to have had poor night vision (link).

- Goodman says Anchisaurus’ only defense was its thumb claw. I disagree. The hindfoot of Anchisaurus appears to have decently-sized foot claws, with the innermost claw being the most recurved and largest (link). I’m not the only one of this opinion either; in The Dinosaur Heresies, Bob Bakker also believes the hindfoot claws of anchisaurs could be used as weapons via kicking (Bakker, 1986). I believe use of the tail is also plausible.

- At least we see Anchisaurus ***** slapping one of the coelophysids (before finally running), so I'm at least grateful that this program depicts basal sauropodomorphs defending themselves. A lesser dino doc could very well have just depicted it as theropod fodder.

- Then we hear a noise that came straight out of a sci-fi robot movie or whatever. It’s Dilophosaurus. Oh god, I love that sound. Kinda ridiculous for a documentary? Probably. Realistic? Probably not. Awesome? Definitely.

- Dilophosaurus then kills the Anchisaurus in a rather brutal fashion, biting its neck, raking it with its hand claws, and throwing it to the side. While Dilophosaurus may not have been munching on Anchisaurus specifically (more like Sarahsaurus, which wasn’t named until long after this doc aired), I’d say this depiction of Dilophosaurus aged well. Since then, we’ve learned that Dilophosaurus actually had more powerful jaws than previously thought, and bite marks on the bones of Sarahsaurus lend support for it being a powerful predator of fairly large dinosaurs.

- Right afterwards, if you look closely, you’ll see that the Dilophosaurus feeding on the Anchisaurus is just reversed footage of it letting go of its victim’s neck. This means the Anchisaurus lifts its neck up on its own. TV Tropes points this out as a clear example of special-effects failure.

- The coelophysids and Dilophosaurus are both stated to be ceratosaurs. By now this is certainly outdated; neither are ceratosaurs. Both are more basal neotheropods compared to the ceratosaurs.

- I actually really like how the Dilophosaurus rakes the Anchisaurus’ carcass with its foot claws. While “normal” theropod foot claws were useful for traction, there’s also evidence suggesting they were useful weapons as well. This is something I feel is underrepresented in paleomedia, barring, of course, theropods with more obvious foot weaponry.

- Lastly, Goodman tells us of the anchisaurs’ destiny to evolve into the largest terrestrial animals that ever lived. In fact, derived sauropodiforms were around as early as the Late Triassic; footprints from the Fleming Ford Formation of central East Greenland have a kind of shape indicative of a eusauropod-like foot structure (Lallensack et al., 2017). These tracks could very well have been made by sauropods proper, but even if not, they do show that the ancestors of sauropods had already acquired this trait before the time this segment takes place in. Therefore, Anchisaurus can’t be the direct ancestor to sauropods proper (which had definitely evolved by the Early Jurassic). It was more of a relatively late-surviving, relatively distant relative that retained a more basal sauropodomorph anatomy.

Final verdict:I think we’re starting to see more of a semblance of a plot in these sequences. The events are in logical, sequential order. You can argue the coelophysids’ conflict is to obtain food (probably the most obvious conflict in this sequence). You can argue that the Anchisaurus’ conflict is to, well, not die. You can argue that the Dilophosaurus’ conflict is to feed not just itself, but also its offspring, and make sure nothing takes those resources from it. We also get to see a time period in dinosaur history that, honestly, isn’t portrayed all that much in paleomedia. Dilophosaurus is arguably semi-well known due to Jurassic Park (and even then probably not that well known to the average person), but how many times have you actually seen the Early Jurassic being depicted? Not even WWD showed it, it just went straight from the Late Triassic to the Late Jurassic (skipping the equivalent of the entire Cenozoic era+2 million years!). So overall, yeah, we’re getting warmer, and nice exposure to the Early Jurassic.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jun 25, 2021 14:17:40 GMT 5

Just had to search for those wonderful sci-fi robot movie sounds on YouTube after reading this.  Anyway, I think it's an interesting idea to critique both the scientific accuracy as well as the plotting (if you want to call it that way). The way you described the Triassic segment reminds me of some of my earliest paleo-fiction "okay, here's a list of creatures I want to appear, let's just cut between them and give them a random scene each with no connection". It also makes me think of the purpose of plotting in these paleo documentaries. Many paleo documentaries do perfecttly fine without tying their educational scenes to story arcs. However, it can make the difference between an episode that's merely good and one that's truly memorable, judging from the reviews we just read. Anyway, as one might expect, I'm looking forward to the next installments of this. |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jun 25, 2021 19:34:45 GMT 5

Yeah, I feel like you can't really review this show without also looking at the storylines of the segments seen here. Partly because both it and scientific accuracy can go hand-in-hand to an extent, but also because, as I said, WDRA is basically trying to be a nature documentary, but with dinosaurs. Even nature documentaries on modern animals will show you at least a short segment where a given animal's "conflict" (i.e. whatever everyday real-life struggle it's going through as an animal) is apparent. They won't show you a sequence of a baby iguana just walking around or doing nothing, without any "narrative" being apparent. They'll show you a sequence of a baby iguana trying to escape from snakes. While WDRA does have a narrative for their Late Triassic segment (Coelophysis is a successful animal in its environment), I felt like they could have done a better job conveying that by having a more compelling plot.

By the way, as I was writing my review, I realized that Planet Dinosaur's 10th anniversary* comes this September (originally aired September 14-October 19, 2011). So does Valley of the T. rex's 20th anniversary** (originally aired September 10, 2001). When the time comes, I plan on making retrospective reviews of these too.

*God I feel old.

**Valley of the T. rex uses footage and models from WDRA, and even modifies some of them. Until now, I never realized just how quickly they adapted that footage and those models from WDRA to Valley of the T. rex.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jul 1, 2021 16:40:36 GMT 5

Late Jurassic segment – Utah, 150 million years ago: Screen capture from When Dinosaurs Roamed America. (Yes, I see that the bullet lists are numbers this time. I don't know why, I thought I put in the same thing for the list. No, I will not bother changing it.) - The dry season is presented as a clear plot point and problem for the dinosaurs living in the Tithonian of Utah. It hasn’t rained for months, stream beds and ponds have run dry, and it’s hot as hell.

- Ceratosaurus was most certainly not the last of its kind. In fact, while it wasn’t the oldest ceratosaur, Ceratosaurus was one of the earlier species thereof. Ceratosaurs survived all the way up to the end of the Cretaceous, just in places other than North America.

- Ceratosaurus ambushes the Dryosaurus family, which is good. It ends up catching one of the youngsters that’s lagging behind, which I think was a nice little aspect of this chase. Ceratosaurus was a rather short-legged theropod, while dryosaurids were highly cursorial. So I doubt Ceratosaurus could catch a Dryosaurus, assuming the later has everything it needs to run as fast as it can (i.e. clear terrain, nothing crippling its body). In general, I think Ceratosaurus was more likely to hunt larger & more formidable, but slower animals (e.g. Camptosaurus, stegosaurs, juvenile sauropods).

- The Camarasaurus’ feet have that one large thumb claw, which is accurate. But they also have smaller elephant-like nails on the other digits, which isn’t accurate.

- I think the documentary implies that Camarasaurus could keep its neck upright with pneumatic neck vertebrae and ligaments holding the head up, unlike most sauropods. In actuality, all sauropods had pneumatic neck vertebrae, and I’m pretty sure neck ligaments were not restricted to Camarasaurus either. My guess is this was influenced by Kent Stevens’ work on sauropod neck posture, which popularized sauropods with horizontal necks in the late 1990s (it shows in both the Diplodocus in WWD and the Apatosaurus in this program). Nowadays it’s understood that the default, habitual neck posture would have had the neck extended and the head flexed, “unless sauropods behaved differently from all extant amniote groups” (see Mark Witton’s art of Diplodocus for an idea of what this would look like).

- I love the description and depiction of sauropods (in this case Camarasaurus) as bulldozing tree destroyers that “could wipe out a forest in no time”. Reminds me very much of elephants, which I tend to think of as basically mammalian sauropods. One of them pushes down a tree with its shoulder, which illustrates the sheer power of these animals well.

- Really love the Ceratosaurus’ roar (yes, I know roaring is more contentious for dinosaurs these days, but I can’t think of anything else to describe this vocalization). Actually, I like that WDRA goes through the effort to give its theropods different sounds. Some dinosaur documentaries give large carnivorous theropods the same vocalizations.

- And Stegosaurus shows Ceratosaurus who’s boss. For some reason, the animators didn’t animate any wounds from the thagomizer. It may be true that more elliptical & keeled (spear-like) spikes (like that seen in Kentrosaurus) are even more specialized for puncturing than spikes circular in cross section (like that seen in Stegosaurus). But obviously, it would be foolish to dismiss their ability to puncture, and we know Stegosaurus could puncture through bone (and thus soft tissue) with its tail spikes (Mallison, 2015). I guess blunt impacts from a Stegosaurus tail strike are still possible (and such a strike would still be damaging, even to a large theropod), but I’m still a bit puzzled by the lack of visible wounds. It’s not like WDRA is averse to showing those.

- We see a brief attempt by the male Stegosaurus attempting to mate with the female, with the dorsal plates being described as akin to a peacock’s feathers by John Goodman. He’s not successful, but as Goodman says, “There’s always tomorrow”. A nice addition in my book.

- The dry season finally ends and the rain brings the wet season, with a few cool bits of the dinosaurs seeing and reacting to the rain. Apparently it brings Apatosaurus to the area.

- "This is Dino of The Flintstones”->.

- We get a bit from Jim Kirkland (there was previously another one, but I didn't feel the need to comment on that). Apparently he says that the virtual lack of sauropod egg remains from the Morrison indicates that these sauropods were not breeding in that location, and were instead migrating elsewhere to breed. He points out that the Morrison has yielded much thinner (and thus more easily destroyed) egg shell fragments.

While I’ve yet to find documentation of conclusive sauropod eggs from the Morrison, I did find a reference documenting embryonic Camarasaurus remains recovered from the Dry Mesa Quarry all the way back in 1996 (link). Not only were these embryonic remains easily small enough to fit in known dinosaur eggs, but their occurrence in the Dry Mesa conglomerate sandstone also suggests minimal transportation from a nearby nesting site. This suggests to me that at least some sauropods were, in fact, breeding in the Morrison. - We finally meet Allosaurus. Is it just me, or does the snout look excessively broad in one shot?

- Interestingly, the Allosaurus does not have some sick roar like Ceratosaurus or Dilophosaurus (or, as we’ll later see, Tyrannosaurus). In fact, it sounds wimpy in comparison (TV Tropes noticed this too). Again, I think it’s really interesting to hear how the different theropods sound in this documentary. It reminds me of how the red-tailed hawk makes that stereotypical kee-eeeee-arr raptor scream that Hollywood uses for literally any bird of prey (presumably to make it sound more “badass”), but the bald eagle makes wimpier, seagull-like noises (although in my opinion, those are actually cool in their own right). Helps illustrate that formidable predators don’t all sound equally terrifying.

- Ceratosaurus chases (what remains of) the Dryosaurus family again, only to be killed by an Allosaurus. The allosauroid doesn’t sound as terrifying, but who cares when it’s significantly bigger?

- The male Stegosaurus’ “story arc” concludes with him finally winning over the female, who lets him mate with her. The calls of the two Stegosaurus fill the air as they mate, with the male raising its head and calling out (almost as if in victory). Complementing this, the music playing in the background is quite a beautiful, idyllic track. This has to be up there as one of my favorite scenes from this segment.

- An Apatosaurus is killed by a group of Allosaurus after it falls off a rock ledge and breaks a leg. My only real gripe with this scene is that the Allosaurus are seen leaping onto the fallen sauropod, which I doubt any land animal of its size could do.

- Goodman points out that the sauropods will live on, while Allosaurus goes extinct. Obviously yes, it does, but it might be worth mentioning that allosauroids weren’t done being apex predators yet, including in America. The last definitive allosauroids lasted up to the Turonian (~92 Ma), only a couple million years before the events of the next segment.

Final verdict:Along with the next two segments, I think the Late Jurassic segment is definitely one of the stronger ones in this documentary. More is going on in this segment than in the previous two, with a larger cast of dinosaurs. Despite this, however, the segment wasn’t hard to follow at all. We see the story come full circle, starting with the dinosaurs trying to survive the dry season, followed by them doing their own things in the wet season (whether it’s mating, munching vegetation, finding prey, or fending off predators), and ending with the Apatosaurus leaving as the dry season returns. So yes, a nicely done segment of the ancient Morrison Formation.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jul 2, 2021 12:09:18 GMT 5

By the way, as I was writing my review, I realized that Planet Dinosaur's 10th anniversary* comes this September (originally aired September 14-October 19, 2011). So does Valley of the T. rex's 20th anniversary** (originally aired September 10, 2001). When the time comes, I plan on making retrospective reviews of these too. Now, I feel the need to review something, too... Can you leave Dinosaur Revolution to me? It aired from 4th September – 13th September 2011 originally. Plus, it's rather ... cartoonish tone will allow a review with conspicious amouts of snark. ]And Stegosaurus shows Ceratosaurus who’s boss. For some reason, the animators didn’t animate any wounds from the thagomizer. It may be true that more elliptical & keeled (spear-like) spikes (like that seen in Kentrosaurus) are even more specialized for puncturing than spikes circular in cross section (like that seen in Stegosaurus). But obviously, it would be foolish to dismiss their ability to puncture, and we know Stegosaurus could puncture through bone (and thus soft tissue) with its tail spikes ( Mallison, 2015). I guess blunt impacts from a Stegosaurus tail strike are still possible (and such a strike would still be damaging, even to a large theropod), but I’m still a bit puzzled by the lack of visible wounds. It’s not like WDRA is averse to showing those. Might be a case of Special Effect Failure rather than a deliberate choice. Ceratosaurus chases (what remains of) the Dryosaurus family again, only to be killed by an Allosaurus. The allosauroid doesn’t sound as terrifying, but who cares when it’s significantly bigger? I vividly remember that bit. I think that was the scene where the camera first focused just on the chase and then Allosaurus popped out of nowhere and toppled the Ceratosaurus over with its head. Made a strong impression on me as a kid. An Apatosaurus is killed by a group of Allosaurus after it falls off a rock ledge and breaks a leg. My only real gripe with this scene is that the Allosaurus are seen leaping onto the fallen sauropod, which I doubt any land animal of its size could do. Yep, one of those things that I didn't care for much as a kid but that now strike me as odd. Final verdict:Along with the next two segments, I think the Late Jurassic segment is definitely one of the stronger ones in this documentary. More is going on in this segment than in the previous two, with a larger cast of dinosaurs. Despite this, however, the segment wasn’t hard to follow at all. We see the story come full circle, starting with the dinosaurs trying to survive the dry season, followed by them doing their own things in the wet season (whether it’s mating, munching vegetation, finding prey, or fending off predators), and ending with the Apatosaurus leaving as the dry season returns. So yes, a nicely done segment of the ancient Morrison Formation. The Late Jurassic of North America (along with the Late Cretaceous) is simply one of those segments that you cannnot skimp or botch, if you choose to include it in your dinosaur documentary. They are so iconic that people will have seen them in other documentaries and compare them to yours. I'm glad that the people behind the storyboard knew this because, from my faint memories of the documentary, this was indeed one of their more impressive segments. |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jul 2, 2021 16:44:55 GMT 5

Sure thing. Since I'll have taken care of three, I should leave one for you, all the more so since that would require me putting out three reviews out at roughly the same time. I honestly forgot DR was that old too.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jul 8, 2021 19:04:17 GMT 5

Late Cretaceous segment – New Mexico, 90 million years ago: Gif source Gif source- Let’s talk about the coelurosaurs and dromaeosaurs.

The bones of what we now call Suskityrannus hazelae were first uncovered in 1997. But paleontologists at the time weren’t sure exactly what kind of coelurosaur it was. They were initially thought to belong to a dromaeosaurid, but two of the scientists working at the Zuni Basin, Jim Kirkland and Douglas Wolfe, told the Discovery Channel that until the specimen was prepared, its identity would be unknown. Discovery Channel went ahead and modeled the dromaeosaurs, only to be told that it wasn’t one at all. So as the documentary was being made, paleontologists learned that these remains were not from a dromaeosaur, but they were also very small for a tyrannosaur (it was only later that histology revealed it was not fully grown). Discovery Channel had to add the generic name “coelurosaur” at the last minute.

Therefore, the “coelurosaurs” are Suskityrannus scaled to known size. The dromaeosaurs were left in WDRA because it was reasonable to assume that they were present in the Moreno Hill Formation. Lo and behold, very, very fragmentary dromaeosaur material (as in, pieces of teeth) was uncovered from the Moreno Hill Formation in the last decade (link).

At first glance, the dromaeosaurids are missing their forelimb and tail feathers (remiges and rectrices, respectively). I mean, they’ve got fuzz covering those parts, but not with the pennaceous feathers they’re now depicted with in those regions. For something from 2001, though, the design is reasonable. - It wasn’t until I rewatched WDRA recently that I realized that Dinosaur Planet recycled its dromaeosaurid noises from this doc.

- Dromaeosaurs do seem to have had relatively large brains for non-avian dinosaurs, but relative brain size is definitely not as reliable of a metric of intelligence in animals as we thought (and that’s putting it nicely). As such, the idea that they were the smartest dinosaurs alive (at the time) like the documentary says is debatable. While they certainly weren't slow, they also were not the most specialized dinosaurs for speed either, due to their leg proportions generally exhibiting greater shortness and robusticity of the lower leg compared to other theropods of similar size (thus, their hindlimbs generally emphasized strength over speed, almost certainly to restrain prey better). The contemporary Suskityrannus exhibits the earliest known record of the arctometatarsalian pes in tyrannosauroids (Nesbitt et al., 2019), and was certainly faster than a comparably sized dromaeosaurid. And while certainly formidable predators…you sure these small predators were the most dangerous dinosaurs alive then? You sure it wasn’t at least a big theropod, or a mega sauropod?

- Yeah, attacking something with long arms and big claws several times larger than yourself…that’s a good idea. It’s a miracle the dromaeosaur is still alive after that arm swipe.

- Welp, there you go. Douglas Wolfe and Jim Kirkland show cranial material from Suskityrannus, and explain what they thought it was at the time. Kirkland says that it may help paleontologists learn more about the origins of classic Cretaceous dinosaurs. He seems to have been right: as a tyrannosauroid, Suskityrannus gives us an idea of what the ancestors of tyrannosaurids might have looked like at the time.

- Not meant to be a complaint, but it’s a little weird to hear 100 kg ceratopsians making the noises of elephants and big cats as they fight.

- One of the dromaeosaurs leaps on top of the loser Zuniceratops and tries to hang on as the ceratopsian bucks around. Its claws end up raking the sides of the Zuniceratops, which prove to be serious injuries later on. Although this is obviously reflective of the idea that dromaeosaur claws were made to slash prey (they weren't; they were primarily meant to pin or hold onto prey), I'm not as mad at this as I could be, at least when I look at it as an extension of “Raptor Prey Restraint”. Real predators don’t use the same killing methods for all of their prey, so RPR doesn’t preclude other means of dispatching larger prey. Not that leaping onto the prey item and riding/raking it is that far removed from RPR, but still. Likewise, just because dromaeosaurid claws were primarily meant to restrain prey doesn’t mean they couldn’t secondarily be used to cut or slash. Just look at felid claws.

- The dromaeosaurids ignore the fire to eat the old Zuniceratops bull they now killed. And then they get burnt to a crisp as all the other dinosaurs (including other dromaeosaurids!) try to escape the forest fire. For the smartest dinosaurs alive, they aren’t very bright, are they?

- Okay, now for something more positive. The track that plays in the last part of this segment is wonderful. It’s my favorite track from this entire documentary (with the Mt. Rushmore track and Stegosaurus mating track being close seconds). Moreover, it fits perfectly as John Goodman explains the future evolution of the dinosaurs. The Nothronychus idyllically browses, and it will evolve into later, even weirder therizinosaurs. The dromaeosaurids run off into the brush, apparently to become smarter in the future. And the Zuniceratops herd is seen galloping off to somewhere through the forest, its kin to “become one of the most famous dinosaurs in North America”. We even get a glimpse of the next segment, as the shadow of a Triceratops plods through and bellows. Just a beautiful scene.

This was a great segment. The plot was relatively interesting, it’s got my favorite track from this documentary (and is implemented very well with the last part, as explained above), and it features a dinosaur ecosystem that is rarely touched by paleomedia. The only other paleo documentary that features the Zuni Basin is Planet Dinosaur, which aired a decade later. The thing with the dromaeosaurids/“coelurosaurs”/ Suskityrannus might confuse modern viewers who decide to do more research, but I can’t blame the Discovery Channel too much for that.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jul 12, 2021 13:42:40 GMT 5

- Yeah, attacking something with long arms and big claws several times larger than yourself…that’s a good idea. It’s a miracle the dromaeosaur is still alive after that arm swipe.

- The dromaeosaurids ignore the fire to eat the old Zuniceratops bull they now killed. And then they get burnt to a crisp as all the other dinosaurs (including other dromaeosaurids!) try to escape the forest fire. For the smartest dinosaurs alive, they aren’t very bright, are they?

When I watched this as a kid, I normally didn't question what I saw in documentaries, but even for me, these moves felt kinda stupid. The droms are suffering badly from Informed Intelligence in this episode. IIRC, they called the dorms "Dromaeosaurus" in the German dub which made me think the genus was meant rather than a generic designator for members of the family. That being said, it was definitely a segment that stuck in my mind and kinda defined the series for me. Like you said, that's an underexplored locality it features here (and I'm definitely expecting call-backs to this during your Planet Dinosaur review). I'm also sorry that my response came to late. I've started trying to avoid distractions during my exam preparation these days, so, I might not reply to segment reviews immediately. |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jul 12, 2021 19:21:04 GMT 5

(and I'm definitely expecting call-backs to this during your Planet Dinosaur review). Oh I'll do my best at that.  I'm also sorry that my response came to late. I've started trying to avoid distractions during my exam preparation these days, so, I might not reply to segment reviews immediately. That's perfectly fine. It's definitely best for you to focus more on academic matters than some forum review of a two decade-old documentary. These reviews will be here once you've got the time to read them. |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jul 13, 2021 5:12:38 GMT 5

Also, I'm going to be uploading this review to DeviantArt as a journal on the anniversary day proper. It's mostly a copy-paste compilation of my reviews here, but with a few minor changes to make things easier for me to post it there. I'll upload the link to the journal entry to Twitter so anyone there who may be interested can easily read my review as well.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jul 15, 2021 16:24:33 GMT 5

End Cretaceous segment – South Dakota, 65 million years ago: Screen capture from When Dinosaurs Roamed America. - The end of the Cretaceous has since been revised to 66 million years ago (see the 2021 International Chronostratigraphic Chart).

- Contrary to what scientists thought at the time, we now know that grass actually did evolve by this point. Long before, actually. The oldest physical evidence of grass I’m aware of are Albian-aged phytoliths found in the teeth of a basal hadrosauroid (so dinosaurs definitely ate grass to if they had the chance), and it’s reasonable that Poaceae actually emerged during the Barremian (as far back as 129 Ma). There’s more evidence of grass in the Mesozoic that I posted here->. This means that grass was probably already around for nearly 40 million years by the time of the previous segment. To be fair, though, while grass was present in the Cretaceous, it wasn’t ubiquitous to my knowledge. I am not aware of any evidence that grass was present in the western United States at the end of the Cretaceous. So Goodman’s statement that the landscape depicted here should not have any grass is correct.

- Can I just take a moment to…

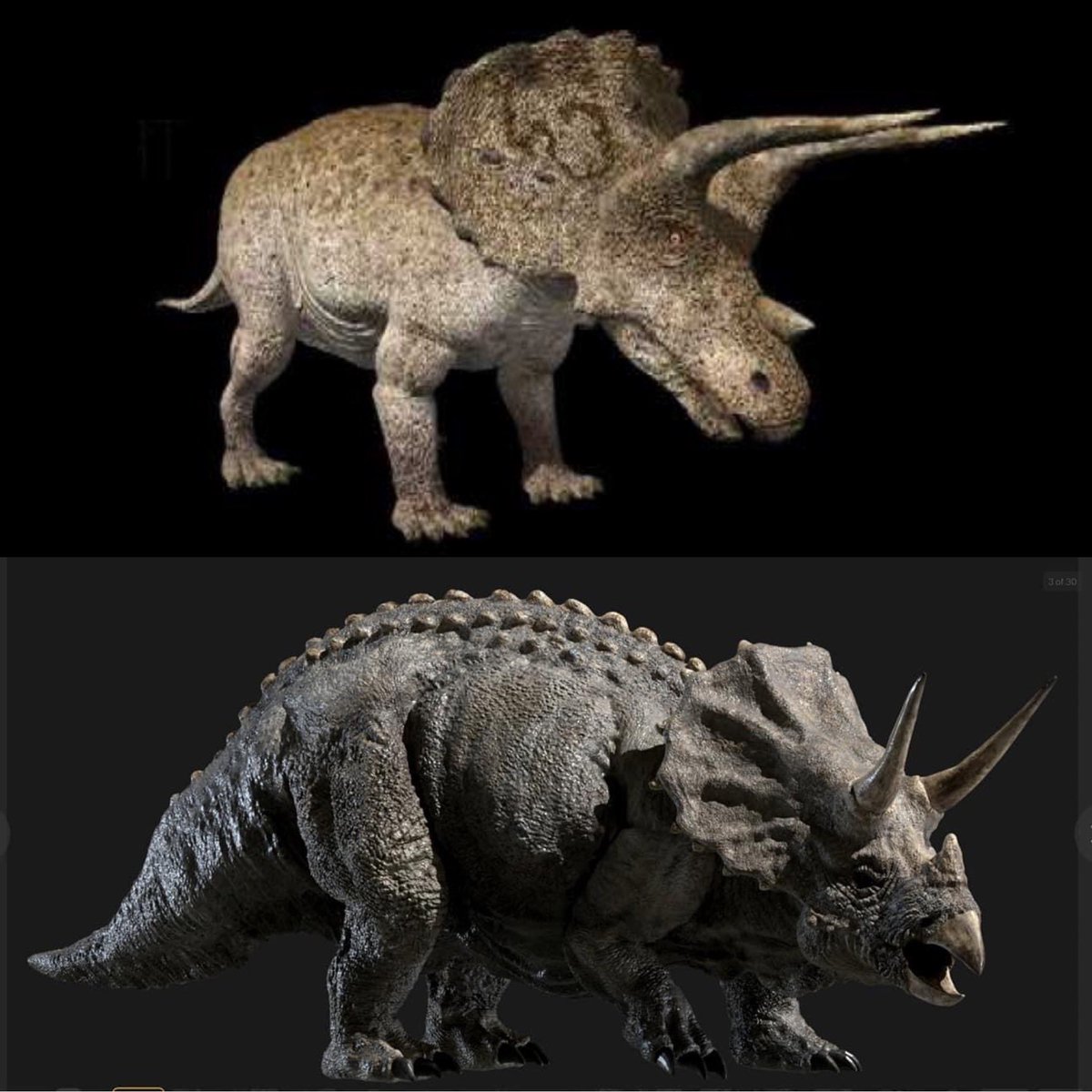

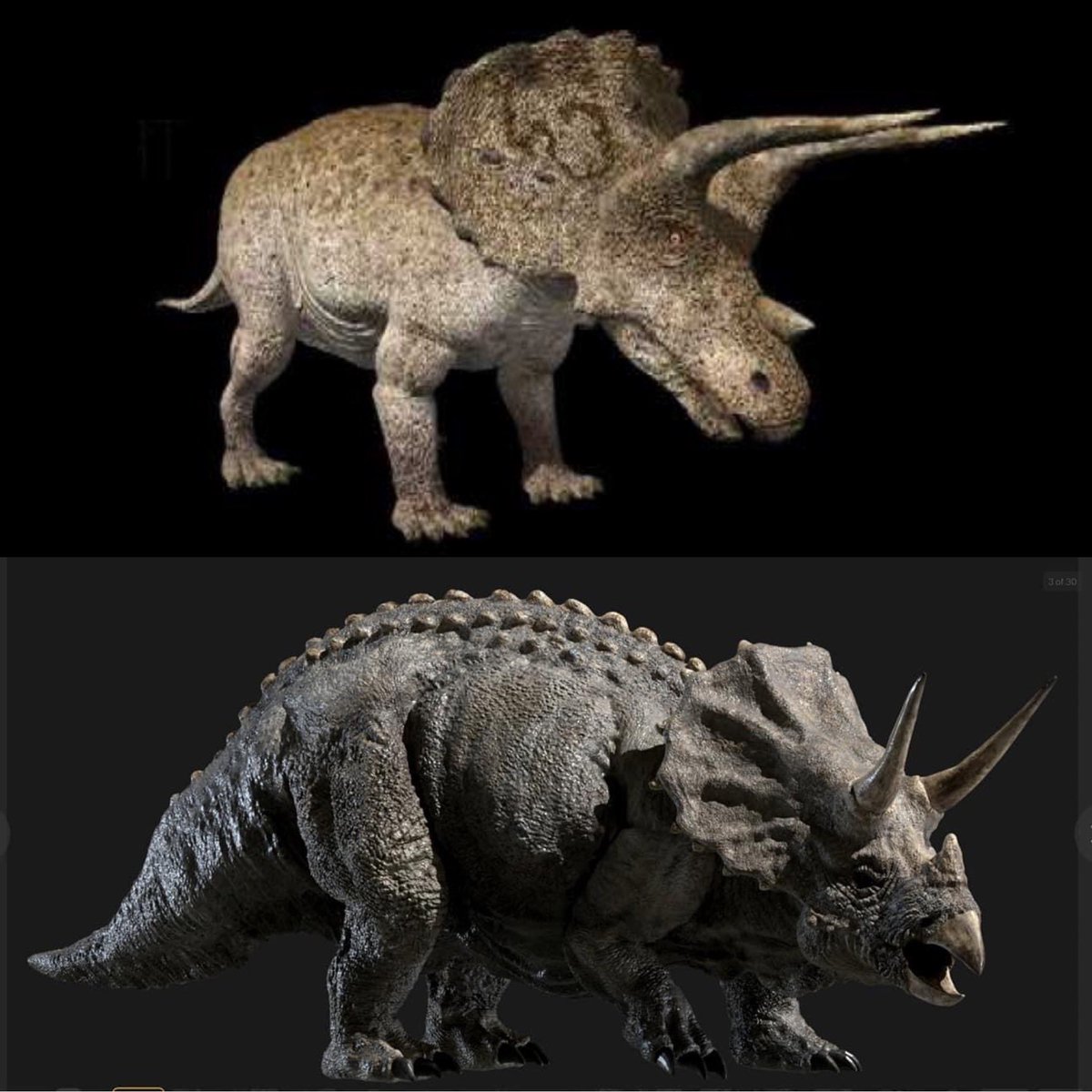

Image source

^The top is the Triceratops model from WDRA, and it’s from 2001. The bottom is the Triceratops model from another Discovery Channel dinosaur show called Dino Hunters…and it’s from 2020.

I’ll give you a moment to cry. - In terms of inaccuracy, the only thing that really jumps out to me about WDRA’s Triceratops model is the shape of the feet, the front feet especially. On the front feet, it’s digits I-III that bear all the weight. Digits IV & V face laterally and do not bear weight. They are small, and do not bear claws/hooves. Given what we now know about Triceratops’ integument, you could also add some large hexagonal scales dispersed over the body, but the animators couldn’t have known that at the time.

- This point is a bit more nitpicky, and I’m not even 100% sure if it’s correct, but the animators seem to have based their Triceratops model more on T. horridus. It is, after all, the more well known species of Triceratops. I say this is because the nasal horn is small and seems to be placed “midway” on the upper snout (it’s really that the beak was relatively longer in T. horridus than in T. prorsus). By contrast, T. prorsus had a much larger and more developed nasal horn, and the beak was relatively shorter and deeper.

The reason I say all of this is that there is evidence suggesting that T. horridus evolved into T. prorsus over time. Skulls showing only T. horridus features are only present in the lower Hell Creek Formation, while skulls showing only T. prorsus features are only present in the upper sections of the formation (Scannella et al., 2014). Since this episode is set literally the day before and the day of the K-Pg extinction event, the Triceratops here would realistically look more like T. prorsus than T. horridus. - Anatotitan was evidently still being used as a genus name (not surprising, since WWD did the same thing 2 years earlier), but it’s not pronounced correctly here (“Anatototitan”). The real name, of course, is Edmontosaurus.

- Edmontosaurus could actually surpass 40 feet. Granted, most adult specimens were much smaller than this (with the smallest adult specimens being >8 meters long->), but specimen MOR 1142 (“X-rex”) was enormous. Estimates put it at around 15 meters long; this detailed post-> (by former member broly) estimates the specimen at ~14.85 meters (so yeah, consistent with ~15 m), which is almost 50 feet in length! Body mass is apparently ~14 tonnes, which is bigger than the biggest recorded African bush elephant. So exceptionally big Edmontosaurus individuals were probably some of the biggest animals in the ancient Hell Creek ecosystem.

- Yeah, hadrosaurs are often called the “duck-billed” dinosaurs, but this perception is based only on the bone core of the beak. There are hadrosaur specimens with the keratinous rhamphotheca preserved, and they show that the upper beak actually angled/pointed downwards, such that the beak edges could crop/shear plants against the lower beak edges (the doc actually says later that the beak would have sheared plant matter).

- We get a segment with Phil Currie where he says that the retreat of the Western Interior Seaway introduced a new climate regime that favored the evolution of larger dinosaurs. Greg Paul said similar things in his Princeton Field Guide, but attributes the underlying selective pressure for larger dinosaurs to the expansion of resources.

While this makes intuitive sense, and while the late Maastrichtian fauna of North America do seem to include the largest members of some dinosaur families (e.g. Triceratops and Torosaurus for Ceratopsidae, and Tyrannosaurus for Tyrannosauridae), there were still very big dinosaurs in the late Campanian of North America. For example, Titanoceratops seems to have been the size of an elephant. We know a couple big Daspletosaurus specimens, namely Pete III and Sir William (apparently this is Pete III’s tail->; it’s 5.1 meters long alone). There’s also evidence of some really, really big hadrosaurids (e.g. the giant Fruitland Formation track that suggests a hadrosaur that may have been bigger than freaking Shantungosaurus!) (Hunt & Lucas, 2003). By contrast, keep in mind that most Edmontosaurus annectens specimens were not 15 meter giants like X-rex either; that same >8 meter specimen I mentioned earlier is closer to the average Campanian hadrosaur in size. So this idea seems to need some rethinking. - WDRA is aware of pterosaur actinofibrils as part of the wing membrane, which is good. By a couple years after the doc aired, it was known that pterosaur wing membranes also had thin layers of muscle, as shown below.

link - The Quetzalcoatlus is mentioned as having no feathers. That’s technically true, but we now know that pterosaurs were covered in pycnofibers. I’m no pterosaur expert, but to my understanding there is recent evidence that suggests that they were actually homologous to avian feathers (Jiang et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2020). I don’t fault WDRA for this, though, as “pycnofiber” was only coined as a term in 2009.

- Also, it’s mentioned to have a wingspan of 40 feet. It’s probably a little less than that, at 10-11 meters (32-36 feet). Later on, though, the Quetzalcoatlus is stated to weigh 200 pounds; it’s more like 200 kg, which is more than twice the weight (Witton & Habib, 2010).

- At one point Quetzalcoatlus is also called a “fish out of water” on land. Azhdarchids today are now thought of as “terrestrial stalkers”, with proficient ability to walk on land and forage for small prey.

- The T. rex that just charged out into the opening and was built up as a giant, menacing killer…is just a 17 foot long teenager. But you would never have known unless John Goodman told you that. Of course, juvenile tyrannosaurids were not just scaled down versions of the adults. Tyrannosaurids went through major morphological changes through ontogeny. A teenage T. rex would be a lightly built, very leggy predator (a later segment with Phil Currie shows that they knew this at the time too). The skull would be more elongated and gracile, and it seems even the forelimbs would be proportionately longer than in the adults as well. Goodman is right that a juvenile T. rex is one of the fastest dinosaurs around.

- Goodman’s statement about nighttime being disadvantageous for predators, of course, depends on the predator in question. For Tyrannosaurus in particular, though, it seems to hold up well today. That recent paper that found that Shuvuuia had such excellent nocturnal senses apparently also found that Tyrannosaurus’ vision indicates it was a diurnal animal (according to news articles reporting the paper). If so, it would support the depiction of T. rex here (and also punch a pretty big hole in the “nightstalker” hypothesis that’s been discussed a bit here in the past).

- Goodman tells us that the female is bigger than the male. WWD did the same thing. Currently, we have no conclusive evidence of sexual dimorphism in Tyrannosaurus.

- WDRA has one of my favorite T. rex roars in all of paleomedia. Even if it’s probably not realistic, it certainly kicks ass.

- Goodman says T. rex’s brain was as big as a gorilla’s. This was Greg Paul’s reaction (I assume he’s talking about the same doc):

“I about kicked in the TV screen when one dino doc claimed that the brain of Tyrannosaurus was as large as that of a gorilla when its IQ was not all that much better than a croc’s.” (link)

To be fair, the doc doesn’t outright say T. rex was as smart as a gorilla, or even that its brain was as relatively large as a gorilla’s (anyone remember that time when news articles said "T. rex was as smart as a chimp!"?). The most you could take from what it’s saying is that its brain was absolutely as large as a gorilla’s, but still much smaller relative to size. The fact that Goodman is talking about how big T. rex’s skull/head is before this makes me believe that this is what the doc meant. - I dunno, I’d hate to be hit in the head by the tail of an Edmontosaurus, even if I were a T. rex.

- The Edmontosaurus are seen chewing like mammals here. Hadrosaurs chewed, but not in this manner (Rybczynski et al., 2008).

- Obligatory theropod roar after it kills its prey.

- One interesting detail I just noticed is that as the Triceratops are running away from the inferno, they’re not galloping. It looks like they’re ambling/fast-walking. This is in contrast to the Zuniceratops we saw in the earlier segment, which are clearly galloping. Even the juvenile Triceratops are seen galloping earlier in this segment (but confusingly, the younger-looking Trikes here amble just like the adults). I believe that ceratopsians were capable of galloping, but probably only up to a certain size. The elephant-sized Triceratops is, in my opinion, most likely above the galloping threshold (although, I still believe trotting is plausible). This isn’t without any basis either; John R. Hutchinson recently wrote in a review that it’s possible that behaviors such as galloping, or even running in general, may eventually be lost in tetrapods that reach or exceed a certain size (Hutchinson, 2021), although it’s not known at exactly what size.

- Goodman tells us that the sun won’t shine again for months. Years after this documentary was made, there have been more precise calculations for how long the darkness from the dust/soot in the atmosphere would have lasted. Depending on the extent of soot injection, 5,000 Tg of soot injection would have kept sunlight at <1% of normal for at least a year. Sunlight would have been severely inhibited for nearly 2 years at 15,000-35,000 Tg (Bardeen et al., 2017). It would actually have been a year or two of darkness. Yikes.

- Phil Currie mentions the apparent decrease in dinosaur species diversity in North America during the last 10 million years of the Cretaceous. Although he doesn’t outright say it here, other paleontologists have claimed this to be evidence of the dinosaurs declining in their last years before the K-Pg extinction event. More recent evidence provides no support for this suggestion (Chiarenza et al., 2019; Bonsor et al., 2020).

- There’s no way I can end this review without talking about the conclusion of this segment. Despite all the devastation the K-Pg brings (the charred T. rex corpse being the most memorable), the documentary shows us how life still moves on afterwards. A turtle survived, mammals survived, and a bird – now the only dinosaurs – survived. A summary of the dinosaurs’ success, with cutscenes from all the segments, is given to us. Some Purgatorius* are seen on top of a T. rex’s skull, signifying the rise of mammals. I’m not sure how to feel about the whole “their children will walk on the moon and think back in awe to a time when dinosaurs roamed America” quote (it’s either poetic or just…dumb), but still, a fine ending to the show.

- *But not before I get one last accuracy nitpick in. Purgatorius is implied here to be an ancestor to humans, something that has been suggested before by paleontologists. This is debatable, and the most recent phylogenetic analysis I'm aware of recovers Purgatorius as a sister taxon to Protungulatum, which is recovered as a non-placental eutherian (Halliday et al., 2015).

Final verdict:This was arguably the most memorable segment in WDRA for me growing up. Maybe part of that was due to my particular fascination with the Maastrichtian dinosaurs of North America (come on, it’s got Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops), but it’s still a nicely done segment. We’re introduced to the herbivores, we meet the largest predator in the ecosystem and learn it’s just a teenager that’s new to hunting, we see them hunt the next day to get a meal (that ends in success this time), and finally, of course, the K-Pg extinction event. A few aspects don’t hold up well today, most notably the hadrosaur’s identification and the proportions of the juvenile tyrannosaurs. In spite of this, it was one of the three better segments in this show in my opinion.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jul 15, 2021 16:30:07 GMT 5

Overall verdict: Commercial break bumper of When Dinosaurs Roamed America. Nothing beats Walking with Dinosaurs, and the Walking with series as a whole, in the history of paleo documentaries. Yet as much as I love, and will always love the Walking with series, that does not diminish the work put into When Dinosaurs Roamed America. Although it clearly didn’t have anywhere near the budget of WWD, WDRA’s dinosaur models are, in general, still nice to look at. Greg Paul was an anatomy consultant for this documentary, and it shows (albeit more obvious at certain times than others). It’s certainly not without its faults (I literally wrote five bulleted lists comprised of thousands of words demonstrating so), but then again, many of its inaccuracies seem to have been products of their time. In fact, if there’s one thing WDRA aged (far) better in than WWD, it’s accuracy. The plots in each segment are not as complex or long as those seen in other dinosaur documentaries (not just WWD, but also Dinosaur Planet, Planet Dinosaur, and Dinosaur Revolution), being rather straightforward. Likewise, you’re not going to feel as much for any individual characters as you would in some other docs (that is, you’re probably not going to cry over an animal’s death like you would over say, the old Tropeognathus in WWD). But honestly, that’s okay. You still learn what you need to know about the animals and the ecosystems they’re a part of. And the fact that you don’t really get attached to any individual animal in this show is a good reminder that at the end of the day, you’re still watching animals as they are (or at least how people thought they were). Realistically, when you’re observing animals in real life, chances are you’re not going to get attached to most of the animals you see. Other things I liked were John Goodman as the narrator (he has a calm, deep, yet explanatory voice), the occasional short segment where a paleontologist or two is interviewed to give context to the segment you’re seeing, and the brief close-ups into the anatomy of the animals (combined with that soft ambient sound you hear whenever this happens). Overall, When Dinosaurs Roamed America is a great dinosaur documentary in its own right. While it may not have the juiciest stories, you still get the fundamental vibe of animals being animals/doing what they can to survive from what’s happening on-screen, and there’s still plenty of action to be engaged with. It still holds up relatively well in terms of scientific accuracy, even if it has its own faults and outdated information/depictions. It therefore takes its place, in my opinion, as one of the best dinosaur documentaries of all time. It sits alongside other “good” documentaries such as Walking with Dinosaurs, Dinosaur Planet, Planet Dinosaur, and Dinosaur Revolution, far, far away from some of the later prehistoric-related crap the Discovery Channel would give us in later years.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Jul 23, 2021 22:26:02 GMT 5

By the way, as I was writing my review, I realized that Planet Dinosaur's 10th anniversary* comes this September (originally aired September 14-October 19, 2011). So does Valley of the T. rex's 20th anniversary** (originally aired September 10, 2001). When the time comes, I plan on making retrospective reviews of these too. *God I feel old. ** Valley of the T. rex uses footage and models from WDRA, and even modifies some of them. Until now, I never realized just how quickly they adapted that footage and those models from WDRA to Valley of the T. rex. Guys, I just realized another famous paleo documentary has its 20th later this year... Walking with Beasts. Now, it still has its anniversary proper a month after Planet Dinosaur's, so I suppose I can still manage it if I really want to do Walking with Beasts (and out of all the ones I was thinking of reviewing, this is the one I want to do the most). I mean, I've been watching and reviewing Valley of the T. rex in advance, so...I guess I can do it? |

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Jul 24, 2021 16:05:00 GMT 5

I’m not sure how to feel about the whole “their children will walk on the moon and think back in awe to a time when dinosaurs roamed America” quote (it’s either poetic or just…dumb), but still, a fine ending to the show. When I was younger, this quote spoke so much to me that I sometimes referenced it on 2012 Carnivora, and made me bring up Purgatorious even when it wasn't the topic. The old times... Speaking of old times: It sits alongside other “good” documentaries such as Walking with Dinosaurs, Dinosaur Planet, Planet Dinosaur, and Dinosaur Revolution, far, far away from some of the later prehistoric-related crap the Discovery Channel would give us in later years. It is very telling that not a single of the titles you mentioned is younger than ten years. The only recent documentary that might come close to them is Amazing Dinoworld (and even then, it doesn't quite have the same feeling). The dino documentary market seems to have stagnated after the epic documentary duel between Planet Dinosaur and Dinosaur Revolution. I wonder if it's simply because the success of WWD caused scores of imitators, but, like any other market trend, the hype simply ebbed off over the years and we're living in the aftermath. Anyway, it shouldn't come as a surprise that I really liked this retrospective overall. Do you think it could be moved to the "Documentaries" subforum? After all, Life has a thread about the scientific accuracy of WWD pinned there, so, "critique" threads about documentaries shouldn't be out of place. |

|