Post by Infinity Blade on Jul 24, 2021 0:31:15 GMT 5

Promotional image for Valley of the T. rex.

“Tyrannosaurus rex did not have 6- to-8- inch serrated teeth and an arc of D-cross-sectioned teeth set in a massive, powerful skull just to consume rotting carcasses! These were killing tools. In sharp contrast are the weak beaks and feet of vultures and condors-the only true living scavengers.”

~Gregory S. Paul (1988)

Yes, we're really doing this. The 20th anniversary of this doc is coming in September too. But I chose to post it earlier because Planet Dinosaur's 10th anniversary is just four days afterwards, and I wanted to put some more space between it and the PD review just so people have more time to look at it and this one. I also wanted more time to review two other docs in advance, and I just wanted to get this one over with. I'll adapt this review to DeviantArt and link to it on Twitter on the actual anniversary day.

- We start off with recycled footage from When Dinosaurs Roamed America, and what is the most accurate reflection of T. rex’s predatory capabilities in this entire program. As you know, Valley of the T. rex recycles footage and CGI models from WDRA, but adds a bit more novel footage, has the dinosaur vocalizations changed to stock animal noises (I wonder why they couldn’t keep the originals), and heavily modifies the T. rex.

- ”And what Horner is finding sets him [Jack Horner] apart from a hundred years of popular belief”. No it doesn’t. As early as 1917, Lawrence M. Lambe proposed that Gorgosaurus (another tyrannosaurid) was a scavenger instead of a predator. He deemed it a sluggish animal and that the minimal wear on its teeth indicated it was a scavenger that got its food through little physical exertion (Lambe, 1917). This, of course, is a very weak argument, not least of which because theropods replaced their teeth. Any tooth that was broken or worn would be replaced.

- Jack Horner tells us that for the longest time no one has ever tested the hypothesis that Tyrannosaurus was a predator, and never brought any evidence to support it. But like I demonstrated above, the “giant theropods were only scavengers” idea was nothing new, and it’s been pushed for throughout this time, well before Valley of the T. rex.

For instance, Greg Paul has had to argue against the scavenger hypothesis in his book Predatory Dinosaurs of the World, which was published in 1988. T. rex was a predator because the tooth wear argument is crap (see above); its feeding apparatus was actually a formidable killing tool, unlike the weak beaks and feet of vultures & condors; and vultures and condors can scavenge because they’re soaring fliers, a luxury T. rex obviously did not have. Giant theropods were slow? But…most paleontologists who asserted this also believed their gigantic prey were even slower…

Again, this was back in 1988. People did question the idea that T. rex and other giant theropods were predators. The predator image stuck because, well, the arguments against it didn’t stack up! - ”Challenging the deadly reputation of T. rex is nothing less than heresy”. Yet people did it way back when.

- Not only is Wankel (MOR 555) nowhere near as complete as this doc claims (>90%; in reality it is 46% complete), it wasn’t even close to the most complete T. rex skeleton found by the time VotT was made. Sue (FMNH PR2081) was discovered in 1990 and is 85% complete. Even Stan (BHI 3033), which was discovered a year before Wankel, was significantly more complete (65%).

- Here we get to Horner’s first major argument: T. rex’s arms are too short for it to get back up and continue fighting (like other predators), to break a fall and prevent injury, or to grasp prey. There is a set of tracks that show evidence of a tyrannosaurid getting up from a quadrupedal prone position on the ground (Caneer et al., 2021). If a T. rex were to fall on the ground, it could certainly get back up (come to think of it, I’m not sure why people think otherwise, considering it would have had to lie down on the ground to sleep and get back up!). This assumes the T. rex doesn’t seriously injure itself if it fell down on the ground, but there is evidence that a tyrannosaurid could survive that as well (see this excerpt-> from Tyrannosaurus rex: The Tyrant King for more details).

And then there’s T. rex’s inability to grasp with its forelimbs. Anyone with at least a modicum of knowledge on various vertebrate predators knows that this is an ignorant argument. There’s a loooooooooonnnnnngggg list of predatory vertebrates (that I’m not even going to bother listing) that lack grasping raptorial forelimbs for predation, and that simply rely on another organ (or set thereof) as their primary grasping tool. For T. rex, that would be its gigantic f*ckoff skull filled with 60 teeth shaped like serrated war hammer spikes. Additionally, traces of pathologies from tyrannnosaurid footprints are suggestive of the use of the feet for restraining large, struggling prey (or fighting other predators) (McCrea et al., 2015), suggesting Tyrannosaurus could also use its feet to help subdue its prey.Out of the 14 tyrannosaurid footprints reported to date, four of which are from Alberta (McCrea et al., 2005. Fanti et al., 2013, McCrea et al., 2014b), eight from British Columbia (Farlow et al., 2009, McCrea et al., 2014b), one from the United States (Lockley and Hunt, 1994), and one from Mongolia (Currie et al., 2003), three footprints from two individuals exhibit remarkable pathologies. This amounts to 21% of individual tyrannosaur footprints with pathologies so far, or 14% of individual trackmakers.

Pedal pathologies, and pathologic tracks, in theropods are not common. A theropod track either isolated or in a trackway, exhibits a characteristic preservation: the medial edge of the foot (digit II) impresses deeper than the lateral edge (digit IV). Digit II is inferred to have relatively more of the animal’s body weight supported on it than digit IV, with digits II and III being the primary weight-bearing digits (Hopson, 2001). Likewise, Lockley (2000, 2007) noted that digit II is typically, shorter, wider and more anteriorly located than digit IV. During the avian step cycle, the subphalangeal pads of all digits contact the substrate simultaneously (Senter, 2009). Assuming the theropod foot moved in a similar manner to that of an extant bird foot (although Farlow et al., 2000 show differences in theropod and avian gait), it is unlikely that the injuries to the digits are the result of normal locomotion. In other words, theropods likely did not contact the ground preferentially with one digit, which might have increased the likelihood of differential stress or injury. It is unlikely that these pathologies were caused by scavenging. It is reasonable to suppose that wounds like this would be caused by restraining large, struggling prey, or fighting with other predators (Tanke and Currie, 2000).

The fact that Tyrannosaurus also has a somewhat larger and slightly more recurved claw on pedal D-II (the strongest toe with the most leverage) is also consistent with the feet (and the claws associated with them) being used as predatory tools. To conclude, T. rex doesn’t need long, muscular arms to hunt. Its skull and neck were enough, and it could even employ its legs. - Jack Horner tells us that the dinosaurs he thinks were good hunters were small predatory dinosaurs like the dromaeosaurids (Velociraptor, Deinonychus, Saurornitholestes, etc.). Of course, dromaeosaurids WERE great predators. Unfortunately, this is followed by a depiction of three tiny dromaeosaurids (seem to be Saurornitholestes) taking on a big hadrosaur (two of them do most of the work). This is the equivalent of three bobcats taking on a rhino. Which is to say, it’s never going to happen.

- Small nitpick: Horner tells us the sickle claw of dromaeosaurids was for slashing. While I agree that these claws could slash/cut, that was not their primary function. Their foremost function was to pin prey down or to keep a hold onto prey.

- Jack Horner is correct that Saurornitholestes was a fast runner. Its lower leg bones were 8.6% longer than expected for a theropod of its femur length (Persons & Currie, 2016). However, what he doesn’t seem to do (or at least is not indicated to have done) is account for allometry when he goes to measure Wankel Rex’s femur and tibia. In non-avian theropods, the length of the lower leg exhibits negative allometric growth with respect to the femur. That is, theropod body size/femur length grows at a “faster rate” compared to the length of their lower legs (Grossi et al., 2019). Persons & Currie (2016) does account for allometry, and they found that Tyrannosaurus’ lower leg bones are actually 11.5% longer than expected for a theropod of its femur length. In other words, Tyrannosaurus actually has more cursorial legs than the same Saurornitholestes Horner touts as the ideal, fast running predatory dinosaur.

- The other thing Horner neglects here is the metatarsus. He only measures the length of the tibia relative to the femur. If we were talking about a plantigrade animal (e.g. a human or a bear), this would be fine. But as a digitigrade animal, Tyrannosaurus’ foot also contributed to its stride length since it was raised off the ground. And like I showed above, its lower leg bones are indeed relatively long for a theropod of its size.

Now, does all this mean Tyrannosaurus was an exceptionally fast runner? No. Tyrannosaurus is still a 6-7+ tonne beast; it’s almost certainly way too big to run extremely fast (particularly as an adult). But Tyrannosaurus was hunting other gigantic animals as its prey. Just to put this into perspective, if Tyrannosaurus were alive today it could certainly outrun an elephant, and should at least be able to keep up with a white rhinoceros, if not outrun it as well. As has been repeated ad nauseam at this point, T. rex doesn’t need to be super fast, it just needs to be faster than its prey, which it almost certainly was (limb proportions of Tyrannosaurus compared to its prey->). - ”I don’t care if T. rex was a predator. Show me some evidence”. This documentary will conveniently ignore said evidence. Evidence that may have been published three years before this documentary (Carpenter, 1998)!

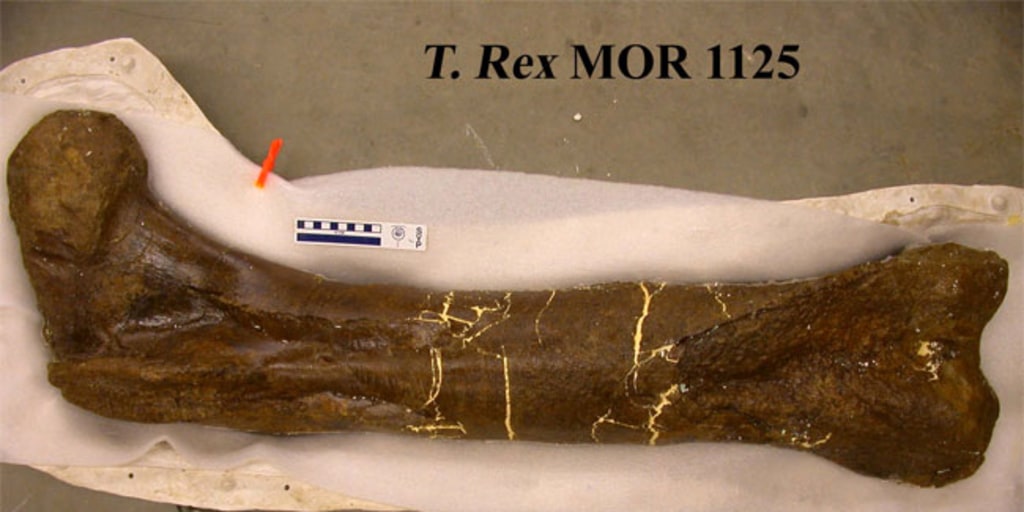

This example I just cited is admittedly more contentious (I remember it was also argued to have been the result of accidental trampling/bumping by other hadrosaurs), but there are other hadrosaurid caudal vertebrae (including bites to neural spines) with injuries indicative of attacks by theropods (including tyrannosaurids). - We get an overview of the fossilization process with a T. rex (particularly the specimen MOR 1128, or “G-rex”). Neat.

- Horner claims T. rex had poor eyesight on the basis of a small optic lobe. But from what I have found, it is debatable as to whether or not you can see the optic lobes in tyrannosaur endocasts (Witmer & Ridgely, 2009), so what he says here based on the Tyrannosaurus brain endocast he has is dubious. On the other hand, other evidence suggests Tyrannosaurus indeed had excellent eyesight. Front to back, the eye socket is about ~13 cm long, which indicates a large eyeball (Carpenter, 2013, in Parrish et al., 2013). It had stereoscopic vision to a similar degree to modern raptorial birds. Additionally, while its exact visual acuity is unknown, estimates based on nocturnal/crepuscular reptiles and diurnal birds as models suggest there is much room between the two extremes for T. rex to have had much greater visual acuity than a modern human (up to >13 times visual acuity, although the author thinks it’s unlikely it reached this extreme). In fact, Kent Stevens even concludes his study by saying that, due to T. rex’s great size and broad frontal vision, it, “…of all sighted observers to have ever lived, might have experienced the most spectacular view of the three-dimensional world”. (Stevens, 2006).

Horner is right that Tyrannosaurus had an excellent sense of smell, on the basis of its huge olfactory bulbs. But all this talk about eyesight and olfaction is moot, because predators and scavengers can make good use of both. Many predators have excellent senses of smell. The turkey vulture may have massive olfactory bulbs to detect carcasses (proportionately as big as T. rex’s, it seems), but Old World vultures don’t. There’s no evidence they locate carcasses via olfaction (Bildstein, 2017), and instead they do it exclusively by sight.

The lesson here is that there’s more than one way to be a predator or an obligate scavenger, as far as detection goes. Both eyesight and olfaction are useful to both. Tyrannosaurus had well developed senses of sight and smell, and would have used both to hunt and scavenge, accordingly. - Footage of the “X-rex” Edmontosaurus (read: that humongous Edmontosaurus) being unearthed. Neat.

- I see your evidence of rex eating a dead Trike and raise you evidence of rex hunting a live Edmontosaurus (DePalma et al., 2013) and hunting a live Trike (Happ, 2008). That is, healed bite marks. Yes, Tyrannosaurus had thick teeth that were rounded in cross section. But those can be useful predatory tools as well. Just ask big cats, mustelids, mongooses, hyenas, crocodiles, and orcas.

- Based on the estimated carcass search rates of Tyrannosaurus (based on assumptions of size, speed, metabolism, and carcass distribution), the giant theropod would, on average, have indeed been second to a carcass. So much so, in fact, that the carcass would likely have been stripped to the bone before T. rex even got there (Carbone et al., 2011). Yes, T. rex was a bone crusher, but bone crushers have to eat meat too.

Speaking of energetics, one study found that the ideal size range for scavenging in theropod dinosaurs is between 27 and 1,044 kg, and even those in this size range can’t live solely off of scavenging. While juvenile Tyrannosaurus could fit that size range snugly, an adult easily surpasses the upper threshold 6 to 8, perhaps even up to 9 or 10 times over. In other words, while T. rex obviously would have scavenged when the opportunity arose, scavenging was probably not a very important source of energy for T. rex or other giant theropods compared to predation (Kane et al., 2016a; Kane et al., 2016b).

Just for comparison, vultures are soaring fliers, so they can travel long distances without expending much energy, allowing them to be obligate scavengers. Tyrannosaurus obviously couldn't do that. Brown hyenas are mostly scavengers that seem to get little of their food from hunting, but they also supplement their diet with fruit, eggs, and insects (Brottman, 2013; Lovegrove & Siegfried, 1993; Unwin, 2011). Striped hyenas, like brown hyenas, are also omnivores (van Valkenburgh et al., 2003). Tyrannosaurus was an obligate carnivore that could pretty much only eat meat. - Believe it or not, T. rex with a red head and a darker body is actually quite an old paleoart meme (link). I admit I actually think it’s a cool color scheme, and it helps make the T. rex model one of the few things I actually kind of like about this documentary.

- Finally, we see Jack Horner’s vision of Tyrannosaurus played out. Technically everything depicted in this sequence could conceivably happen. Maybe the Tyrannosaurus isn’t too far away from a carcass and was lucky enough to get there before it’s stripped to the bone by other carnivores. It could just brush aside the Edmontosaurus in favor of an easier meal.

Now just depict this rex hunting something.

Overall verdict:

[Life reconstruction of Sue the T. rex feeding on a young Edmontosaurus. Did it kill it? Or did it just find its dead body? Either is possible.]

Congratulations Tyrannosaurus rex, you survived your greatest fang corking.

It tells you something that Horner himself didn’t actually formally publish this hypothesis in peer-reviewed literature (he wrote a book about it with Don Lessem, though). He supposedly just wanted to use it as a vehicle to warn against making assumptions in science without evidence. And hey, the predator-scavenger "debate" does seem to have inspired a number of interesting papers and books with interesting findings on Tyrannosaurus.

Regardless of Horner’s motivations, this basically resulted in the general public thinking that this was a genuine scientific debate, when it never was. See this old episode of PaleoWorld from 1994; Phil Currie and Pete Larson (both dinosaur paleontologists) are on record saying that Tyrannosaurus would have both hunted and scavenged (link). Again, 1994. To this day you could probably still find pseudointellectuals online who think Tyrannosaurus was a pure scavenger, or at least that Jack Horner had good points, thanks to all this snafu.

One thing I noticed about this documentary is that the only paleontologist you ever see give his input about Tyrannosaurus' paleobiology (or anything, really) is Jack Horner himself. Never once do you hear any counterarguments for T. rex being a predator, let alone any counters to said counterarguments. The predator hypothesis is portrayed purely as one big assumption that served as the foundation for 100 years of T. rex-mania, without any evidence supporting it. Which, of course, is not true. There were plenty of dinosaur paleontologists (in fact, arguably the vast majority) who believed that T. rex could have hunted for its prey if need be. While I'm not saying no one should ever make a documentary that leans towards or advocates one side of a debate, you should at least consult the other camp and hear what it has to say, and then address that. This is something you literally learn when you're in high school writing an argumentative paper for English class. Interestingly, other documentaries that covered T. rex in the '90s or early 2000s did consult Jack Horner and heard what he had to say about its feeding habits, even if in the end they concluded that it was indeed a formidable hunter. Valley of the T. rex could easily have shown the same courtesy, but it didn't.

If nothing else, I am lowkey fond of the Tyrannosaurus model here for some reason (though its depiction as a pure scavenger is certainly wrong), as well as some of the bits where the intricacies and difficulties of fossil hunting are explained.

But overall, this dinosaur documentary can basically be summed up as 50 minutes of "T. rex-was-a-scavenger" propaganda. Not only has every single argument brought up in this program been shot down with a counterargument, and not only is there is now direct evidence that Tyrannosaurus hunted its prey, but the arguments never held up all that well to scrutiny to begin with, in spite of its major theme to examine evidence and arguments. It is disingenuous. Although Valley of the T. rex is from the era of the really beloved and well known paleo documentaries, it does not help that legacy. The best thing you could really say about this program is that it gives you a good idea of the thought process behind a debunked premise, and how not to present a "paradigm shift" to the general public.