Sea Monsters (Walking with) – A Retrospective Review

Nov 2, 2022 1:33:48 GMT 5

Life, Grey, and 1 more like this

Post by Infinity Blade on Nov 2, 2022 1:33:48 GMT 5

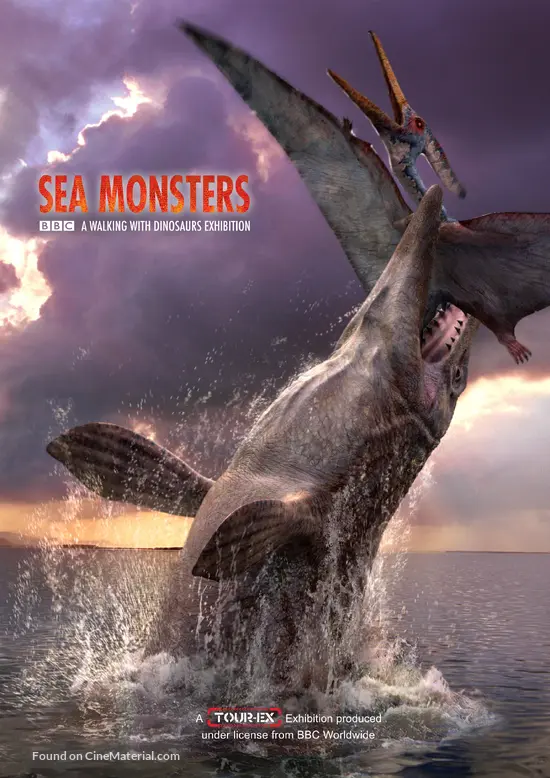

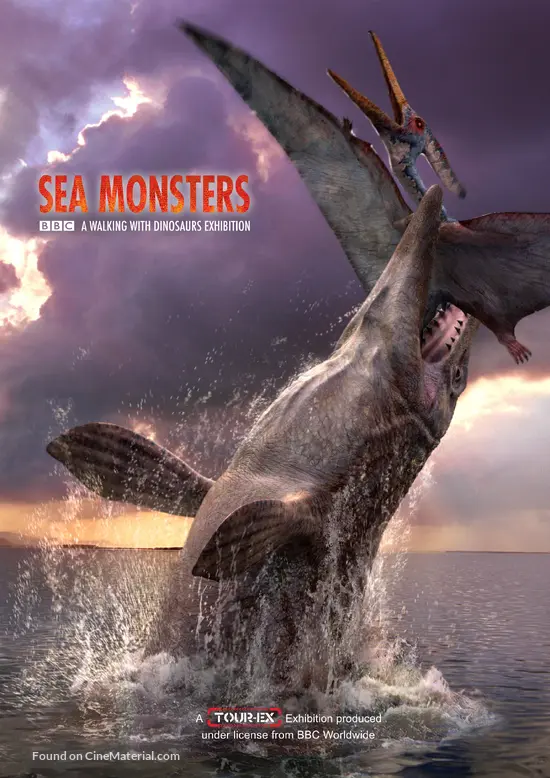

Sea Monsters – A Walking with Dinosaurs Trilogy: A Retrospective Review

About 71% of the Earth’s surface is covered in water, and of that water, the oceans hold 96.5% of it (USGS->). Indeed, life on Earth began in the oceans, dating back to at least 3.5 billion years (Schopf et al., 2017). Ever since then, the seas have been filled with countless lifeforms that lived and died throughout the ages. Some stayed in the oceans, some left, and some who left even came back. And some were undoubtedly terrifying…

This series of posts will review an old BBC documentary that holds a special place in the minds of many: Sea Monsters – A Walking with Dinosaurs Trilogy. It follows Nigel Marven as he travels back in time to visit the “seven deadliest seas” of the Phanerozoic (although, as you’ll see through this review, how “deadly” an ancient sea was is kind of arbitrary), treating us to an expansion of the BBC’s Walking with universe. Although it hasn’t quite been 20 years since it aired, I was inspired to review this anyway after seeing a mini-review on Twitter. So put on your diving gear and maybe get a speargun ready! Because we’re going to dive into this (figuratively, but not actually literally).

Directory:

- Dangerous Seas (this post)

- Into the Jaws of Death->

- To Hell...and Back?->

Verdict:

Some inaccuracies are noticeable in this first episode. I’d say most of them are probably just cases of science marching on, although a few were never quite accurate to begin with (either being exaggeration or just flat-out made up). Nevertheless, it’s by no means all outdated material. The eurypterids seem to hold up to this day (at least from what I can tell), as does the orthocone with the exception of its horizontal posture (and I guess size?). The Cymbospondylus is regarded as a serious hazard, which is rightful in my opinion despite its likely piscivorous habits.

Because this are the first and thus “least deadly” seas, things haven’t gone too awry so far, although I’d say you could argue that they start to become a little this way by the time Nigel encounters the Dunkleosteus. I know Nigel never really gets hurt again after this episode, but I forgot if things ever go really wrong eventually. We’ll see.

About 71% of the Earth’s surface is covered in water, and of that water, the oceans hold 96.5% of it (USGS->). Indeed, life on Earth began in the oceans, dating back to at least 3.5 billion years (Schopf et al., 2017). Ever since then, the seas have been filled with countless lifeforms that lived and died throughout the ages. Some stayed in the oceans, some left, and some who left even came back. And some were undoubtedly terrifying…

This series of posts will review an old BBC documentary that holds a special place in the minds of many: Sea Monsters – A Walking with Dinosaurs Trilogy. It follows Nigel Marven as he travels back in time to visit the “seven deadliest seas” of the Phanerozoic (although, as you’ll see through this review, how “deadly” an ancient sea was is kind of arbitrary), treating us to an expansion of the BBC’s Walking with universe. Although it hasn’t quite been 20 years since it aired, I was inspired to review this anyway after seeing a mini-review on Twitter. So put on your diving gear and maybe get a speargun ready! Because we’re going to dive into this (figuratively, but not actually literally).

Directory:

- Dangerous Seas (this post)

- Into the Jaws of Death->

- To Hell...and Back?->

- We start off with a montage of Nigel Marven running from various theropods in the two-part Chased by Dinosaurs series (I still need to review the second episode of that). The narrator, Karen Hayley, has an awesome line: “…no matter how bad things get on land, the one thing you should never, ever do, is get in the water”.

- This is accompanied by Nigel jumping into the sea off of a cliff to escape a pursuing Tarbosaurus. While he’s safe from the Tarbosaurus’ grasp (if this were Speckles the Tarbosaurus, it might’ve been a different story lol), a Xiphactinus swims right past him soon after entering the water.

- From the get-go, we’re shown the order in which Nigel will travel to (although, if you’re not familiar with the history of life on Earth or its named periods, you may still be puzzled), and that each sea will be “deadlier” than the preceding one. From “least” to “most deadly” we have the Ordovician, the Triassic, the Devonian, the Eocene, the Pliocene, the Jurassic, and the Cretaceous. Again, whether or not you really agree with the ranking here is up to you. Personally, I’d say the period with the two largest macropredators that ever lived plus a whole slew of other terrifying oceanic predators is the most intimidating (the Miocene), but that’s just me.

It also may be worth asking “deadly to whom?”. If we’re solely talking about how deadly to humans, that adds another layer of complexity to the ranking, as we have no real way of knowing how aggressive any of these predators would be to humans had they lived with us. For example, we live in an age where elephant-sized macropredatory dolphins chomp and ram everything from small fish to whales to death, yet these same dolphins only very, very rarely attack humans in the wild. Similarly, I might consider megalodon to be the most physically powerful predator seen in this documentary, but would a megalodon really see a skinny primate three orders of magnitude smaller than itself a good meal (so there’s room to disagree with me as well)? - Nigel has this really cool (but super long) map of the history of life on Earth with him. When I was a little kid, I actually tried making one myself. Good times, good times.

- Forgive me for any mistakes I make here. The early Paleozoic is not my strong suit.

Anyway, we first travel to the Late Ordovician 450 Ma (this would put us at the Katian). The track and the overall barren look of the landscape do a good job of showing us an alien, inhospitable world (this track comes back when Nigel realizes that Earth’s days were shorter back then, further giving us the impression of an alien planet). There are no insects flying around, no worms in the soil, and no plants on land.

But from research I did while reviewing this, it appears there actually were plants on land at this time after all. Evidence for embryophytes (land plants) goes all the way back to the early Middle Ordovician, over 470 million years ago (Strother et al., 1996; Rubinstein et al., 2010). Molecular clock studies also support the appearance of embryophytes between the middle Cambrian and early Ordovician (Morris et al., 2018). Also, evidence of burrows has been described in an Ordovician paleosol (Shear, 2000). The kind of terrestrial environment shown in this segment (no worms, no soil, and no plants on land) certainly existed at one point, but it appears to have been even earlier than shown here. - The people making Sea Monsters apparently went through great pains to get their animals right. The eurypterids, the first animals we see here, are an example. The team sent a bunch of emails to Simon Braddy, a paleontologist at University of Bristol. He said that “They sent me several e-mails so I could comment on the way they had made the eurypterids...Their first model was not very good at all, but in the end I think they had got it just right” (link->). Now, I’m no invertebrate expert, and of course, paleontological knowledge has expanded a lot since 2003. But from looking at this anatomical diagram of Megalograptus-> (the genus depicted in Sea Monsters), I’d say it looks about right too.

- Nigel gets the base of his legs cut up by the eurypterid’s pincers. I’d probably shit my pants if those pincers made any sort of contact with my skin, Jesus Christ.

- Nigel and the crew spend the night at the Ordovician beach. I wonder, did they have those oxygen masks hooked up to their faces so they’d get enough oxygen while sleeping?

- The next morning, Nigel goes out to the middle of the bay with a large trilobite carcass he found the day before as bait for the real creature he’s after: giant orthocones (apparently supposed to be Cameroceras). He also has a camera hooked up to the carcass to get a view of whatever comes over to scavenge. Although it takes a while, an orthocone finally grabs ahold of the corpse and the camera goes offline. When he dives down, he sees a Cameroceras swimming around and even feeding on the sea scorpions.

But how big is Cameroceras, really? Historically, Cameroceras was a wastebasket taxon where other endocerid genera were placed. This included Endoceras giganteum, the largest verified shell of which was 5,733 mm (5.73 meters) long (Klug et al., 2015). I don’t have a published paper on the largest Cameroceras (only these two pieces of art by Fabio Alejandro->), but it looks like the really giant sizes can’t be assigned to Cameroceras. - More recent work also suggests that, contrary to many earlier depictions, most species of orthocone would not have been able to swim well if oriented horizontally. Instead, they likely lived their lives oriented vertically (Peterman & Ritterbrush, 2021), as seen in this reconstruction->.

- Nigel leaves the Ordovician with a horde of eurypterids climbing onto his boat, and moves on to the Triassic (PETA would definitely get on his ass for throwing some of the sea scorpions out of his way). Since the segment is set 230 million years ago, we’re looking at the Carnian here.

Nigel sees a Coelophysis run by on the beach and then just moves on. “Dinosaurs, been there, done that”, he’s probably thinking. - Nigel rides a Nothosaurus (which would definitely get him in hot water with PETA). He’s able to do so by grabbing the back of its jaws to prevent it from biting him, stating that although they have powerful jaw-closing muscles, the jaw-opening muscles are very weak (as in crocodilians).

How much does this align with reality? While the skull of Nothosaurus does have a lot of room for jaw adductors (despite it being very narrow, elongated, and longirostrine), it also shows evidence of a strongly developed depressor mandibulae muscle (as you can see here->, marked ‘dm’), which opens the jaws. This powerful muscle and the strong epaxial muscles suggest Nothosaurus could open its jaws rapidly. So for an animal with strong muscles for rapidly opening the jaws, Nothosaurus would probably require more effort to keep its jaws closed than a crocodilian. The powerful adductors suggest it could snap its jaws rapidly as well. What we’re looking at here is an animal that would swing its head to the sides to rapidly snap up fish and small to large soft-shelled invertebrates (although, small pachypleurosaurs and small cyamodontoid placodonts have been found in the stomach contents of another nothosaur, Lariosaurus) (Rieppel, 2002). - Nigel comes across a Tanystropheus foraging on the ocean floor. There has been debate over the years as to whether Tanystropheus was a terrestrial or aquatic animal. For what it’s worth, the most recent study, which involves a three-dimensional reconstruction of the skull of T. hydroides (previously thought to be a “large morph” of the genus, but turned out to be a novel species), found that the nares were placed on top of the snout and that the dentition was much like a fish trap. This suggests the skull was specialized for aquatic hunting. However, the overall body plan of Tanystropheus was poorly hydrodynamic and the limbs had limited adaptations for an aquatic lifestyle. If it was aquatic, it certainly wasn’t a fast or efficient swimmer. It’s thought, therefore, that Tanystropheus was limited to coastal environments. It would have been an ambush hunter, laterally swinging its head to snap up fish (similar to Nothosaurus) (Spiekman et al., 2020), just as Nigel claims here.

- But then Nigel grabs the reptile by the tail, only for it to escape by having the tail detach, like in modern lizards. This, of course, is not supported by fossil evidence. Lizards with detachable tails have fracture zones running vertically along each relevant caudal vertebra, which work like the perforated lines in paper towels.

- The detached tail Nigel holds in his hands is then eaten up by a Cymbospondylus, the real sea monster he came to see here.

How big is Cymbospondylus? It depends on the species. Some species weren’t anything special in size, but others, like C. youngorum were huge. How huge depends on who you ask. One recent study tried to estimate the size of this ichthyosaur using the size of the humerus as a proxy, resulting in a whopping 17.6 meters long and 44,698 kg (Sander et al., 2021). But in his recent Princeton field guide on Mesozoic sea reptiles, Greg Paul tones this down five-fold, giving us an animal that’s more 14 meters long and 9 tonnes (Paul, 2022). Personally, the latter somehow sounds more sensible to me.

Here’s a size chart with multiple species of Cymbospondylus together (link->). Despite the uncertainty in size, even the smallest specimen on there is pretty impressive in size. - And keep in mind that this sea reptile was not something to sneeze at either, despite its snout and dental morphology. Although the prey taken was probably not humongous relative to its size, it’s not like it would have been restricted to tiny fish or cephalopods either. An ichthyosaur with grasping teeth and a long snout, Guizhouichthyosaurus (5 meters long), was found with the remains of a 4 meter thalattosaur in its stomach. The smaller reptile was most likely killed, then dismembered by the larger ichthyosaur. According to the authors, the thalattosaur was roughly one-seventh the body mass of the ichthyosaur (Jiang et al., 2020). Extrapolating this to the size of C. youngorum (assuming it weighed as much as Greg Paul estimates), we’d be looking at prey items weighing as much as ~1.3 tonnes (depending on how rough “roughly” is).

- Ngl, the track that plays as the Cymbospondylus tests Nigel as a prey item is pretty nice. Suspenseful and dramatic. Unlike the orthocone, the ichthyosaur at least considers taking a bite out of the time traveler, so I guess they weren’t lying when they said they aimed to make each sea deadlier than the previous.

- Right after Karen Hayley introduces us to the Devonian, the camera pans to Nigel looking down on his time map and pointing to one part, with a sound effect as if he’s dipping his finger into water (accompanied by ominous “time” sound effects, for lack of a better word). Then suddenly, DEADASS RIGHT AFTERWARDS, Nigel turns his head to the viewer to talk to them. It’s just an abrupt transition that I couldn’t help but chuckle a bit.

- Nigel tells us how mind bogglingly vast deep time is. Which…yeah. The amount of time between his first and second adventures in this episode is 220 million years. That’s literally the amount of time separating creatures like Coelophysis and Postosuchus and you. To the Triassic reptiles of the Carnian, the orthocones and eurypterids were already ancient as balls.

- A Dunkleosteus is filmed on their first dive, and is said by Nigel to be 30 feet long and 4 or 5 tons, weighing as much as “two or three elephants”. The highest recent estimates for Dunkleosteus suggest it may have been up to 8.8 meters long (Ferrón et al., 2017) and I don’t know how heavy. If Dunkleosteus weighed that much (4 tonnes doesn’t sound unreasonable), it would absolutely not weigh as much as two or three elephants, unless you’re referring to African forest elephants (which I doubt he is). 4 t is the weight of one bull Asian elephant.

- The Dunkleosteus model also seems to be out of date. I can at least point out that the tail would have actually been shaped more like a shark’s than what it used to be depicted as (Ferrón et al., 2017). I’m not sure about anything else beyond that.

- Nigel catches a Bothriolepis with a fishing rod as bait for the Dunkleosteus. He gets in a round shark cage (it’s round under the logic that the jaws of large predators would slide off of it, akin to a dog biting a beach ball) to lure it. After an encounter with a Stethacanthus (which is not actually a true shark as claimed here*) Dunkleosteus eventually arrives. It bangs the cage to a worrying extent, and the episode ends with a close-up of the Dunk.

Verdict:

Some inaccuracies are noticeable in this first episode. I’d say most of them are probably just cases of science marching on, although a few were never quite accurate to begin with (either being exaggeration or just flat-out made up). Nevertheless, it’s by no means all outdated material. The eurypterids seem to hold up to this day (at least from what I can tell), as does the orthocone with the exception of its horizontal posture (and I guess size?). The Cymbospondylus is regarded as a serious hazard, which is rightful in my opinion despite its likely piscivorous habits.

Because this are the first and thus “least deadly” seas, things haven’t gone too awry so far, although I’d say you could argue that they start to become a little this way by the time Nigel encounters the Dunkleosteus. I know Nigel never really gets hurt again after this episode, but I forgot if things ever go really wrong eventually. We’ll see.