|

|

Post by dinosauria101 on Feb 13, 2024 21:28:45 GMT 5

Image by the BBC. All images unless stated otherwise are also from the BBC. I'm not going to mince words: there is too much to say about Walking with Dinosaurs in the simple intro to do it any justice. So I'll keep it simple: this 1999 giant of a palaeodocumentary that has been viewed, reviewed, and providing inspiration infinite times very much deserves its place among our documentary review roster. However my dear reader, this review isn't just going to be like any of the more 'standard' reviews, if that's what you were expecting. This review will be entirely based on the show's entertainment value - as much as I have talked about entertainment-reviewing it, I have NEVER seen a pure entertainment review, so this should bring something new to the table. Furthermore, this review will be of a perhaps more different tone than expected. Having watched and reviewed more documentaries than ever before, and having substantial changes of opinion, I will reflect upon this in my review: for example, how my new opinions are reflected or how watching new documentaries makes me appreciate certain things about Walking with Dinosaurs. Infinity Blade will be writing a more standard review as well, and of course, any other member is welcome to give their thoughts too. The reviews for each episodes are as follows:New Blood (this comment) Time of the Titans (->)Cruel Sea (->)

Giant of the Skies (->)

Spirits of the Ice Forest (->)New Blood: -We begin Walking with Dinosaurs with an intro that can only be described as a combo of opera and primordiality. Deep, somewhat opera-esque music booms as we see a montage of moments of WWD’s animals in various colors and against various backgrounds, beginning with a sunrise and ending with a T. rex roar+thunderstorm. Although it has nothing on the Walking with Monsters intro in my opinion, I do quite like the variety we are shown, and the way it appropriately advertises WWD’s wide-reaching coverage and epic tone. -Then, Kenneth Branagh (the narrator*, as well as one of my multiple all time favorite narrators) tells us to imagine traveling back in time. We watch as we speed-shift to clips from Death of a Dynasty, Time of the Titans, Giant of the Skies, Cruel Sea, and finally New Blood, as the stage is set for telling us what WWD is all about. Way to go, WWD! This sort of intro is enthralling and hooking beyond words in my opinion, and the documentaries that have intros with this premise are markedly memorable for it. -*A note on Kenneth Branagh as a narrator: watching some David Attenborough documentaries and learning that the initial plan was for David Attenborough to narrate WWD has made me very glad Branagh was the narrator. This comment from the Reddit user TheSalamanderKing21 sums up perfectly the reasons why I am so glad for Branagh's narration: -That very first New Blood footage is in a 220 million year old harsh, red-soiled desert (filmed in New Caledonia), and it comes with a very ominous, deep, and foreboding yet alluding soundtrack - the first besides the intro of WWD’s awesome, spectacular, masterpiece soundtracks! Bravo Benjamin Bartlett! We also get the very first of WWD’s infamously awesome practical effects: some dinosaur/reptile skull and a Placerias head animatronic that is foaming at the mouth (my favorite Placerias shot in the episode). -As we see more Placerias march on, Branagh tells us about how the Triassic has seen many different varieties of ancient reptile come and go. Although this very obviously couldn’t have been a reference thanks to being 6 years before, it definitely reminds me of my favorite WWM episode Clash of Titans (which featured said reptiles) - I very much appreciate this reminder in hindsight of my WWM reviews. -“But now out of this dry wilderness has appeared something revolutionary. A family of reptiles destined to shape the course of life on Earth for the next 160 million years. These are the first dinosaurs, and this is where our story begins”. The first of many awe-inspiring quotes Branagh was given in his lines! We are told this as some Coelophysis appears on screen with a primordial yet delicate soundtrack - I looooooove this model with its red, green, yellow-white, etc stripes and patterns, as well as its very ‘small dinosaur-sounding’ sfx. -More ahead-of-their-time WWM flashbacks! There is another very primordial-sounding piece playing as we get a Placerias grazing at sunrise, while Branagh tells us about how ancient reptiles previously ruling Pangaea for over 50 mya have had their day. Come to think of it, now that WWM is my GOAT palaeodocumentary and having reviewed it, I take far more note of these flashbacks than ever before. And I can’t help but wonder what flashbacks there would be had WWD been made after WWM. -Grim evolutionary battles, proving grounds, and supremacy over a strange world! Even more WWM flashbacks in what follows - with of course more primordial music still. I guess this is pretty appropriate given how evolutionarily focused New Blood is on the progress of early dinosaurs, as well as its overlapping with WWM as far as being Triassic is concerned. Which is a pretty nice thought. -The wet season has just ended, with the local river being full, but 9 months with no rain is right around the corner - something the Coelophysis are good at surviving thanks to needing very little water. -Following this, we get a Coelophysis hunting a lungfish, with a slow, building-up, hunt-appropriate soundtrack. She is described by Branagh during the buildup as “light-boned, fast, and beautifully adapted for killing”, which in my opinion hits the bullseye sweet spot of providing a substantial description without dragging on. 2 things I like about the hunt are the fact that we get animatronic Coelophysis head closeups (although I am not a fan of the lungfish-eye-view one because I can’t quite see the patterning I like, we get a standard closeup which more than made up for it), and the fact that the gore of eating the lungfish is not shied away from whatsoever (unlike documentaries such as Prehistoric Planet that are remarkably egregious in this regard). -As the Coelophysis eats the lungfish, Branagh tells us about the usefulness of special hips and ankles the dinosaurs had together with their lightning-fast reactions making them built to survive, which is a point the Coelophysis then demonstrates perfectly by fleeing nimbly from an oncoming bellow. -Following that, a bellowing chorus of Placerias are in search of some water: their bellows are very appropriately deep for large, burly beasts and one of my favorite things about them. As they drink, we get both WWM flashbacks (Branagh reminds us that these are of a rather ancient lineage, with formerly many species despite the endangered Placerias being the only ones) and an animatronic head closeup. -When they finish their drink, we get an explanation as to their tusk function (mostly for digging up roots, but can be lethal weapons on 2 angry males), and presumably the same Coelophysis female from before targeting the old, weak animals in the herd (although failing in the end). -Afterwards, we get an introduction to the cynodonts (rightfully described as one of the Triassic’s most bizarre animals). Branagh tells us different things the cynodont has in common between mammals (having fur, living down a burrow, feeding young with milk) and reptiles (having its backbone move side-to-side as it runs). -For the around-the-burrow-shots, more fabulous animatronics are used, and some very ‘homey’ sound effects from both of the parent cynodonts as they care for their young and carry out domestic chores. Which is all solidified as being homey as Branagh tells us the bond between cynodonts is extraordinarily strong, being animals that pair for life. -And to end our intro with the cynodonts, Branagh states “In the not-too-distant future, small, furry mammals will evolve from reptiles like these). I find this another WWM flashback considering we went that way with Edaphosaurus/Dimetrodon, the gorgonopsid, and Diictodon/Lystrosaurus. -Back to the Placerias: they are grazing…..but things turn fearful as the largest land carnivore on Earth (and a distant cousin of the dinosaurs), Postosuchus, appears and attacks one with a bite to the leg. I find the Postosuchus model, the roars, and the soundtracks all very fearsome (which Branagh’s narration is extremely appropriate to outline in my opinion). Plus I also love the reddish purple color on the model. -The Placerias gets away initially, but the Postosuchus is easily able to keep pace, and Branagh states ‘Eventually a combination of shock and blood loss defeats the wounded Placerias’, which I found to be a scary thought- as did I find the scene where the Postosuchus digs in. -We move back to the river: further into the dry season, it is the only place where vegetation remains lush, and animals such as the pterosaur Peteinosaurus are attracted to it. I adore both the CGI model and the animatronic head closeup. There is also another WWM flashback (Meganeura) showing and telling us about how dragonflies are aerial predators that evolved long before the dinosaurs. Which is followed by the Peteinosaurus eating the dragonflies, and seeing the wings in both the animatronic’s mouth and floating down the river solidifies this scene. -Also at the river: both the Placerias and the Postosuchus (for which we get more intimidating soundtrack) need to get a drink, although since the Postosuchus has recently eaten her fill, she is of no danger while she drinks. -“The only creature on the planet she fears is another Postosuchus”. Really solidifies Postosuchus’ apex predator status in my opinion! -As the dry season drags on, it gets to the point where smaller rivers are drying out, and the animals do what they can about such hardship. A Peteinosaurus (with more animatronic closeups) risks a cooling bath in one river, while elsewhere the cynodonts (more animatronics!) remain in their burrow throughout the hottest part of the day. “But no animal here is truly safe”. Indeed Branagh, indeed. -As the soundtrack turns intimidating, the female Coelophysis (which we get an animatronic head for) and other individuals pick up the scent of the cynodont’s bedding and begin investigating their burrow. Yet, as Branagh says, it is clear they have never met cynodonts before - a fact solidified by their fleeing when the male cynodont comes out of the burrow to investigate. -Later on, the Postosuchus needs food once again, but sustained a tusk wound from her last hunt Branagh even forewarns may well prove to be fatal. And its seriousness is evident as she fails to make a kill. -After the failed hunt, we see the cynodont young developing now: they can start to move about the nest, but they need to remain under their parent’s protection for the next 2 months. The male prepares to hunt, and a youngster follows him to the end of the burrow…..where he is promptly taken and eaten by a Coelophysis! He has responded too late to his youngster, and although he drives the Coelophysis away once more, they do not go far. -Throughout this scene we get animatronics of both animals. -But trouble is brewing. A thirsty male Postosuchus has invaded the wounded female’s territory, and with her being too weak to fight, she must simply surrender her held-for-a-decade home as the male urinates to mark it as his - which is an emotional moment in my opinion. -More trouble, of course, continues to brew for the cynodonts. The Coelophysis have started to dig them out, forcing them to eat their own young (more animatronics for here) so the dinosaurs are denied food and the adult cynodonts can escape at night. An even more emotional scene in my opinion, especially considering Branagh describes eating their young as shattering a unique bond. And I like how the night scene is not dark to the point of being unwatchable, unlike documentaries such as Prehistoric Planet. -Once they escape, the Coelophysis still return thanks to the cynodonts’ smell remaining. It will take time for them to realize their work is in vain. After the wasted effort, our female finds another lungfish in a dried-up riverbed, but thanks to an increase in Coelophysis numbers, is not alone to eat it for long, She gets into a squabble as several others appear. -This increase in Coelophysis numbers also causes changes in their behavior. A behavior change for which we get an initially ominous and intimidating soundtrack change to somber. A flock of them have united to bring down the wounded female Postosuchus (for which some very appropriately gnarly animatronic closeups are given) - although her jaws obviously present a risk, her losing the use of her back legs makes her a viable target. -However, eventually her strength fails, and the Coelophysis are able to eat her from the inside out because their long snouts can reach under her thick scales - Branagh’s description of them eating her from the inside out fits perfectly. -After the kill, the drought drags on further than usual, and we get the same dinosaur skull/foaming Placerias animatronic as the intro. The Placerias are forced to migrate elsewhere in search of water, while the Coelophysis are thriving thanks to wasting very little water when they excrete and so being able to better handle the drought. In the WWD universe, the success of the Coelophysis is eliminating most other reptiles, and with little other prey available they must turn cannibal. We get my favorite Coelophysis animatronic here: an adult with a half-eaten baby in its mouth. -That night, we see that the cynodonts have survived, and dug another burrow hidden with ferns. The male catches a baby Coelophysis while hunting as it is the only common prey - I view this as a sort of ‘revenge’ for the Coelophysis eating the baby cynodont lol. -Things only get better from here! Appropriately accompanied by orchestral music, we see that finally the rains are returning and the drought is over. The female cynodont (animatronic) in her new burrow has laid a new clutch of eggs. This will pay off in their mammalian descendants, but for the next 160 million years, the mammals will be clinging on as small species in a dinosaur-ruled world - and outside that future is already arriving. -Here we get the end scene for New Blood, which is also my favorite scene! The female Coelophysis and many of her kind have survived the drought, but they are also joined by a herd of huge 4 ton Plateosaurus - which come with extremely majestic opera music and a fabulous color pattern. They rear up and splash in the river with their massive bulk, and it is very telling. -"This is the shape of things to come. The age of the dinosaurs has dawned". A truly phenomenal end statement right there. Overall Verdict:What an absolute banger of a beginner episode for entertainment value! The animals' struggle throughout the drought is made well clear throughout substantial storytelling, the narration is perfectly executed, the music is epic and somewhat WWM-esque, the animatronics+sfx give the animals much personality, and the substantial number of WWM flashbacks are incredibly pleasing, to name just a few. Accompanying this is eye-candy visuals: when watched in 1999-esque low resolution the animals do look quite good, and as I mentioned, I adore so many of the colors. And at the end of the day, the overarching narrative of the days of the dinosaurs beginning couldn't have been driven home better. So overall, an incredibly enthralling start. Can't wait to review more.  |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 13, 2024 21:48:48 GMT 5

Walking with Dinosaurs – A Retrospective Review So… Walking with Dinosaurs is going to be a quarter of a century old once October rolls around this year. The age of this documentary also puts into perspective how old I am at a given time. And I don’t just mean that in a “Oh if you remember this you’re old” kind of way, I mean it literally too. Seriously, I was born just six months before the first episode of Walking with Dinosaurs aired on television. So…how does it hold up? I’m far from the first person to review this series, and even people from ten or maybe fifteen years ago would have come to the same general conclusion about it that I eventually will. Let’s just say for now that I still LOVE this series to death, but two and a half decades is a loooooonnnngggg time for additional research. So…you up for a review of the series? Well, even if you’re not, too bad, because I’m doing it anyway! I’m going to be doing the same as I did for the Walking with Beasts review. Every episode I review will also be hyperlinked to this OP under the directory, with the first episode being part of this post. Directory:- New Blood (this post) - Time of the Titans->- Cruel Sea->- Giant of the Skies->- Spirits of the Ice Forest->- Death of a Dynasty->New Blood (Arizona, 220 million years ago): - That rising sun with the orchestral music is iconic in my head. The whole title sequence is, actually, even if that of Walking with Beasts is by far my favorite in this entire trilogy.

- As the footage travels back in time, you can briefly see a windmill appear and disappear, indicating that the animators put in a bit of work into detail, showing human structures that would have come and gone throughout human history. Neat.

- If you pay attention to what Branagh is saying after you’re taken to different points in the Mesozoic (the end of the Cretaceous, the Late Jurassic, and then the Late Triassic, which is when this episode takes place), he says some pretty striking things about the Earth from this time that may very well shock you (especially if you’re not a paleontology-buff). When introducing the general audience into dinosaurs, I think this is a good move.

- I’m not sure how much of a fan I am of the “briefly preview the later episodes of this series” style of introduction in WWD, though. I’m perfectly cool with just starting right at the beginning of the Triassic, or maybe a bit before that during the time of the Permian extinction (the catalyst for the proliferation of reptiles in the Triassic, including dinosaurs).

- ”These are the first dinosaurs…”

Later you’ll be told that dinosaurs actually appeared ten million years before (which they indeed did, maybe even earlier than that, actually). - So this episode takes place 220 million years ago in Arizona. Throughout the episode, you’ll see this episode depicted as a dry, desert-like environment, albeit with a wet season that looks reasonably lush (like in the beginning and end of the episode). This is presumably based on the Chinle Formation, and looking at what others have said online, this indeed appears to be the case. But what was the Chinle Formation actually like at the time?

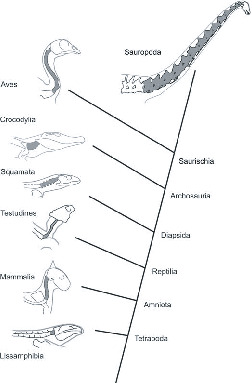

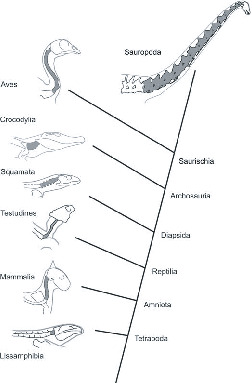

I had to use a previous review of WWD to help me out for this one (which I spent some time looking for to no avail, only to find it in a casual search; link->). It actually had quite a lot of rivers and lakes. So much so that there were large fish, metoposaurs, and phytosaurs wandering in those bodies of water. It also had dense vegetation. It was only in the later Owl Rock member of the Chinle Formation (207 Ma) that the environment actually became arid. - Branagh mentions a group of reptiles that once ruled Earth for 50 million years that, by this point, “…have had their day” while the camera is focused on a lone Placerias grazing. It’s clear that the program is referring to the non-mammalian synapsids that were the dominant large land animals during the Permian. It was common back in the day to refer to these creatures as “mammal-like reptiles” (in fact, this is exactly what I was taught and subsequently called them as a child). Nowadays, we recognize that this term is misleading (as synapsids, they share a more recent common ancestor with us mammals than they do with any true reptile such as lizards, crocodiles, or dinosaurs); terms like proto-mammals or stem-mammals are better. So for the time this isn’t anything egregious, but if we were making this now it would be more truthful to call them proto- or stem-mammals (which may actually add to their intrigue to general audiences).

- The build-up that comes from the music as Branagh narrates the context of the Triassic and dawn of the dinosaurs is pretty nice. We’re shown the star of the episode (and the whole program for that matter) walking through the fern prairies and to a river bank. The close up of the Coelophysis’ face (from an animatronic or puppet) and the shot underwater as its reflection looms over still look pretty good to me even after all these years.

Granted I’m watching this on Internet Archive and it’s not in HD or anything of higher resolution, which masks any appearance of the CGI that betrays its true nature. - The Coelophysis running at break neck speeds at an off-screen animal bellowing (I’m pretty sure Placerias) is really cool.

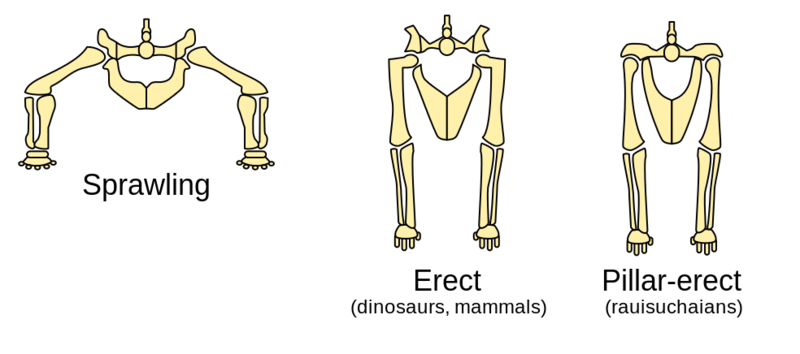

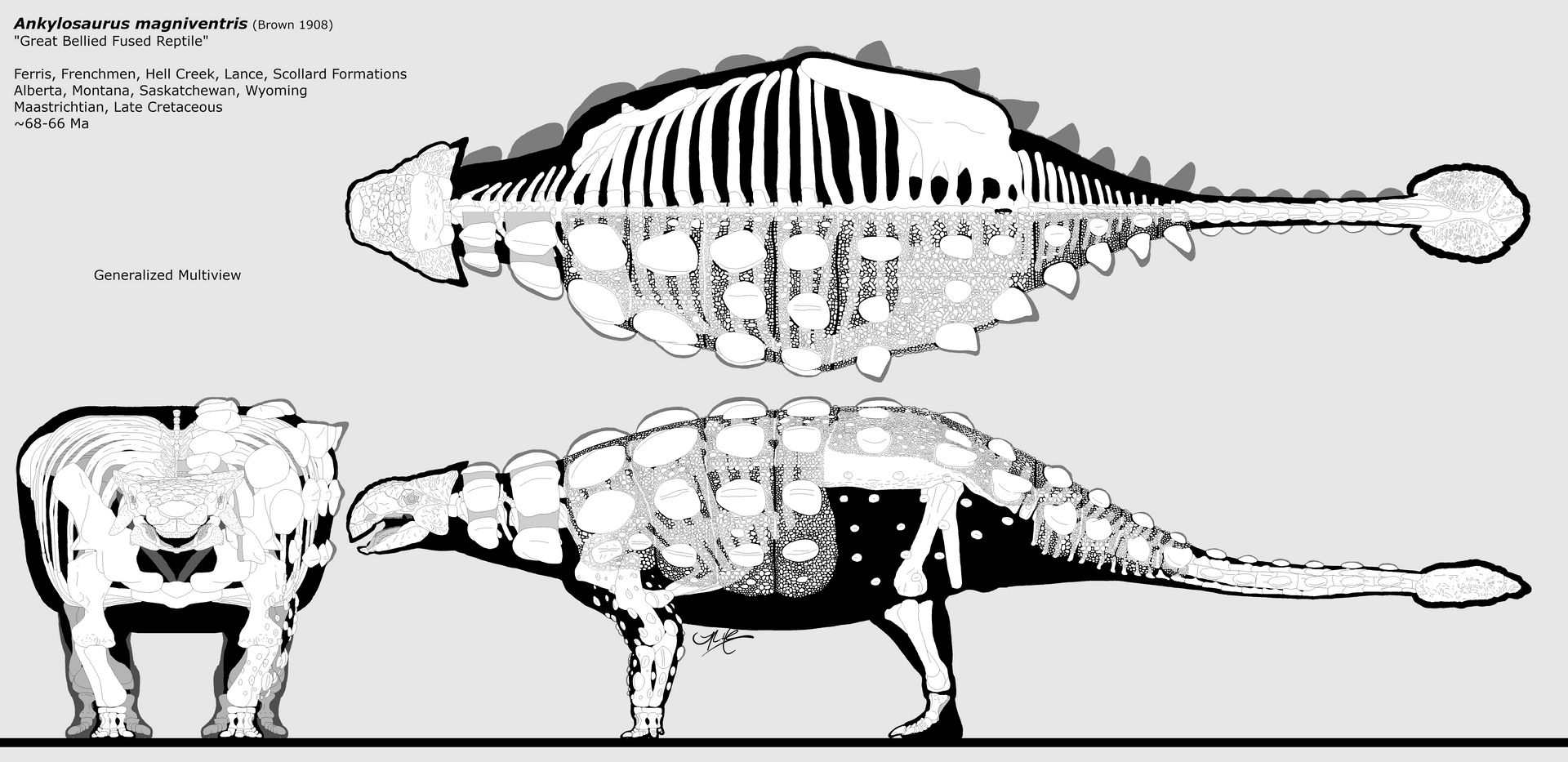

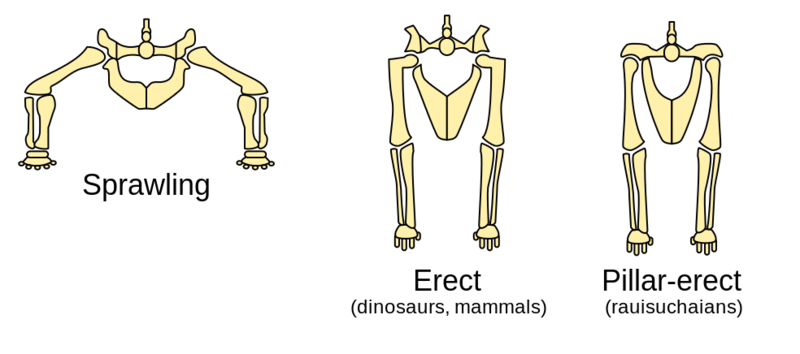

- Now, one thing I should mention here is something about the narration. It’s said that dinosaurs have special hips and ankles that allow them to walk perfectly balanced on two legs. While this is (obviously) true, bipedalism was experimented with by other Triassic reptiles. Some of the pseudosuchians of the Triassic were also bipedal (e.g. Effigia, Poposaurus, and another example we’ll meet later on), they just didn’t have the same ankle or hip anatomy with the dinosaurs (you can see this in the two images down below).

Croc ankle on the left, dinosaur ankle on the right. - So what are some things to note about the Placerias?

The first is a dicynodont thing in general. At the time WWD was made, Placerias was one of the only dicynodonts known from the Late Triassic at all, and it was the only one known from outside of South America. It was also one of the youngest dicynodonts known. This led to the impression that these dicynodonts were on their way to extinction. Since then, we’ve since learned that the last dicynodonts (the stahleckeriids) were actually still widespread across Pangaea, were still diversifying, and they were certainly around until the very end of the Triassic. They even produced their largest form (Lisowicia).

Secondly, although the dicynodonts are so-named for their two tusks, the Late Triassic dicynodonts didn’t always have them. The two prominent sharp things jutting out of Placerias’ face were actually horn-like protrusions from its beak (these are the caniniform processes). Some specimens of Placerias actually did have true tusks, but they were small and stubby, being completely hidden from external view by those same beak horns. Additionally, there are actually two morphs of Placerias, one with those beak horns, the other without. This variation is not correlated with size and appears to be evenly distributed, so it’s thought that this may reflect sexual dimorphism (the suggestion being that the “horned” individuals are males and the “hornless” individuals are females). This was actually known back in the 50s(?), but the publication reporting this was really obscure (and still is, I think), so this will get a pass from me too.

(Interestingly, I think this may imply the same thing for other stahleckeriids. Ischigualastia and Lisowicia are commonly said to lack these elongated caniniform processes, and known specimens do. But maybe those are just “hornless” morphs of their genera.)

(If you want more details about these two things, I suggest you read this nice blog post->)

Third is that..man, these things are slow. With their extremely stocky builds, true, dicynodonts would not have been especially fast or long distance runners. But even massive, relatively slow-moving megaherbivores today are still capable of being surprisingly fast (by our standards). So WWD portraying the Placerias as unable to move beyond a snail’s pace irks me (we’ll see this same issue with another animal later). - ”For the swift Coelophysis, Placerias are prey.”

You ARE referring to very young Placerias, right?

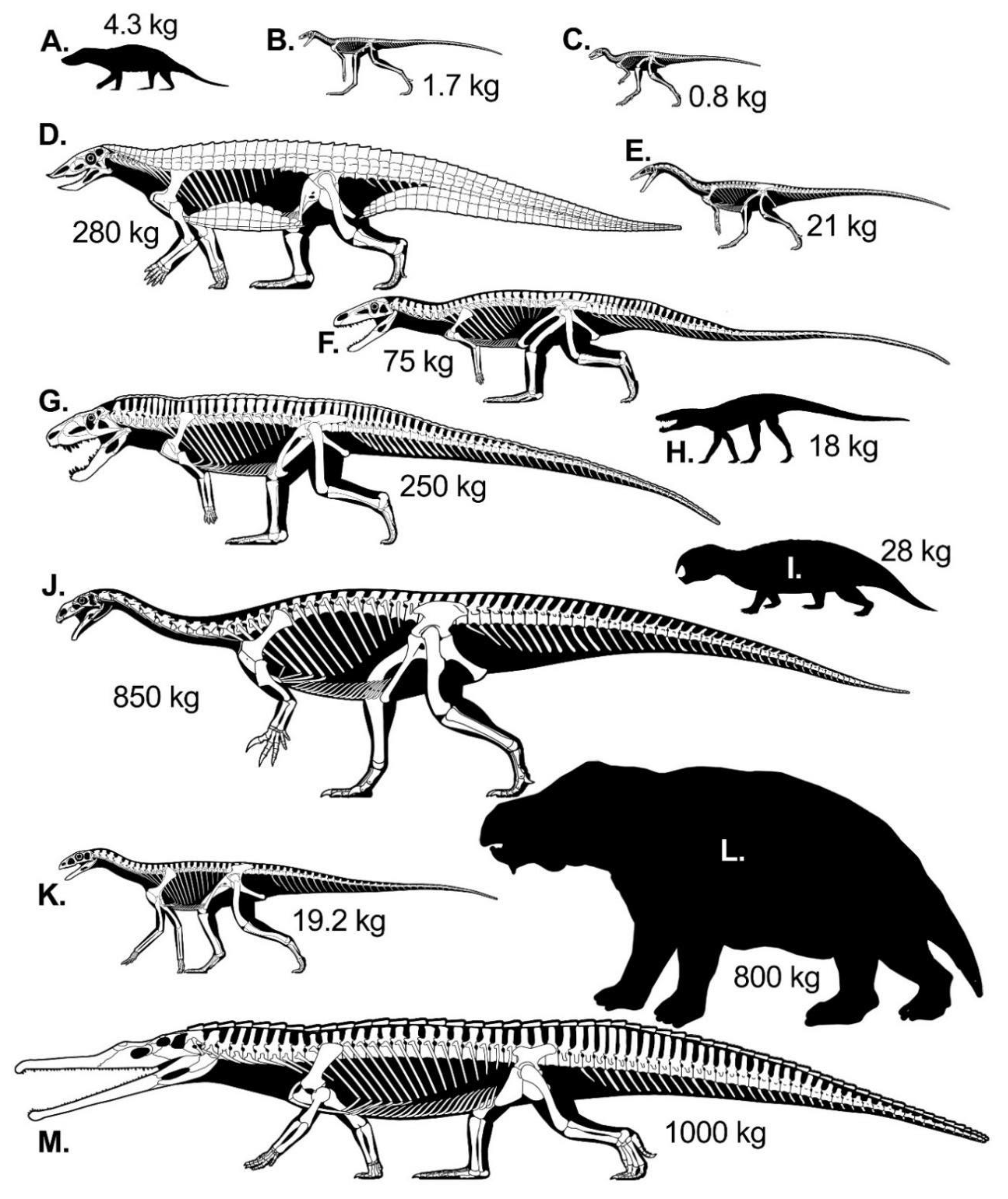

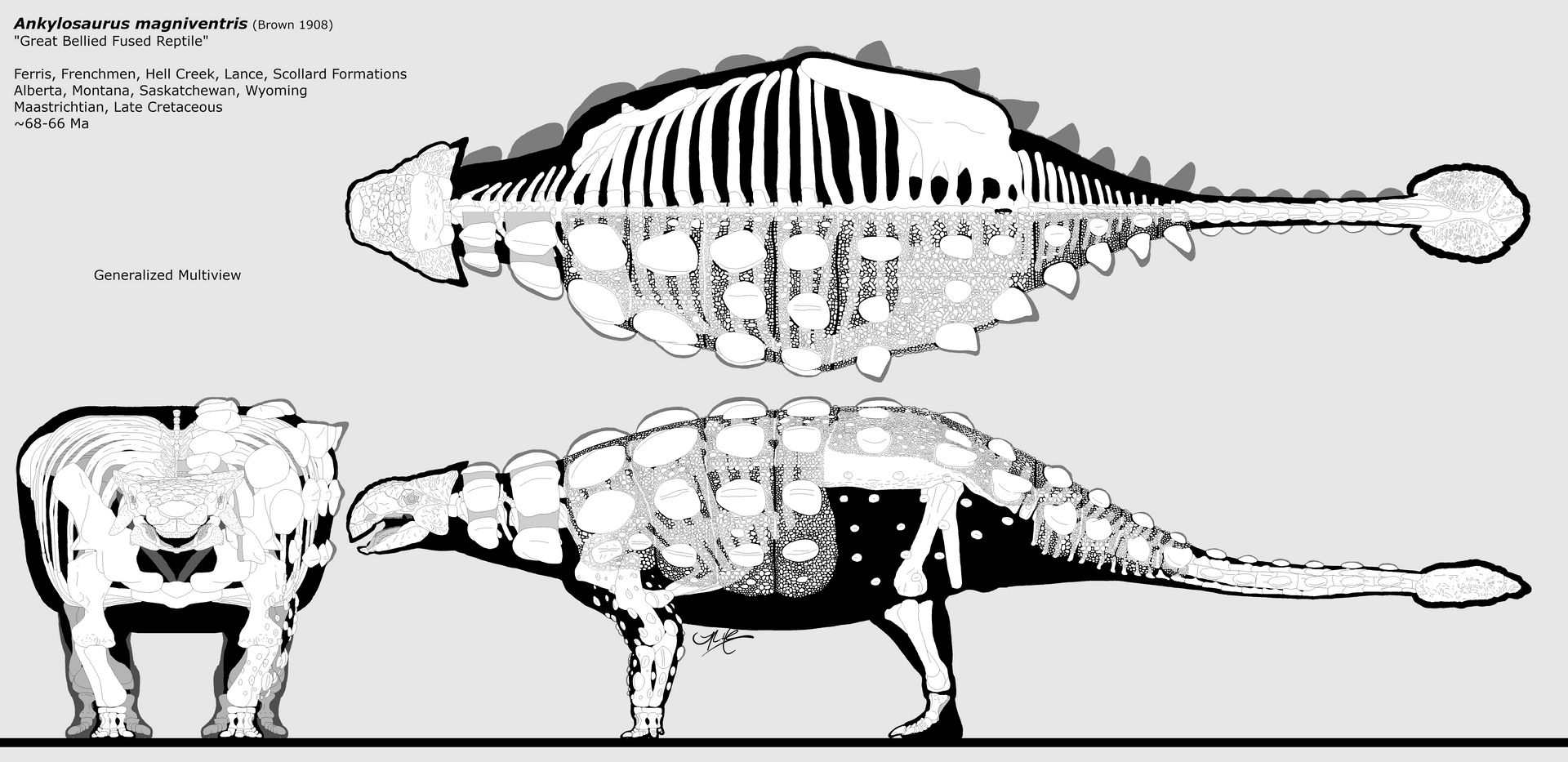

Hartman et al. (2023)

^E is Coelophysis, L is Placerias. Not sure what business the Coelophysis thinks it has with the Placerias. Just to be an @$$hole? Well, I guess that’s theoretically possible. But prey the Placerias is not to Coelophysis. - The next animal we meet is an unidentified cynodont. This cynodont is portrayed as a “missing link” between reptiles and mammals (note that we don’t use the term “missing link” all that seriously anymore), weening undeveloped young that hatch out of eggs (seeing the puppets for their young always disgusted me as kid).

The companion book reveals that the cynodont’s appearance is based on Thrinaxodon. The fossils that directly inspired the WWD cynodont were two large teeth attributed to large cynodonts found in the Petrified Forest of the Chinle Formation. However, these teeth were originally attributed to traversodont cynodonts, which were herbivorous animals. This means that at the time, WWD was taking some liberties basing their cynodonts on the predatory Thrinaxodon.

Later in 2005, these teeth were dubbed Kraterokheirodon colberti. But, while WWD can be excused for not reflecting this, a surprising conclusion was reached about these teeth: we don’t know what kind of animal these teeth belonged to! The most we can tell about Kraterokheirodon is that it was an amniote…and that’s about it.

The amniote affinity was suggested by the evidence pointing towards a thecodont tooth implantation (i.e. a tooth root sitting in a socket in the jaw bone). While the teeth do have some traversodont features, they are too different from them to be identified as belonging to the group (Irmis & Parker, 2005). So to this day, we have this mystery creature known only from teeth from the Triassic. - The male does domestic chores during the day while the mother nurses the young. Cynodonts don’t care for your gender norms! ;p

- Hope you liked this tender scene with its calm, soothing music. Because now it’s time for something to die.

A Placerias herd is attacked by an ambushing Postosuchus, which grabs the leg of one and pulls back. The Placerias actually seem to move a bit faster than usual, but still not especially quickly. And then Branagh properly introduces us to Postosuchus, the lower-pitched Howie scream-roaring* apex predator of the Late Triassic.

*I’m serious, the Postosuchus’ roars in this documentary are the slowed down Howie scream (link->). - Unlike what was known at the time (and thus depicted in this documentary), Postosuchus doesn’t actually seem to have been “too front heavy” to walk on two legs. It is now believed to have been a biped like the earliest dinosaurs, but unlike them it seems to have been plantigrade.

(Skeletal by Scott Hartman)

Of course, there were still quadrupedal “rauisuchians”, just not Postosuchus, which makes it even more interesting IMO. - I want to take this moment to note an obscure fact about Postosuchus. Both known species (at the time WWD was made, only P. kirkpatricki was known) possessed a single relatively large, laterally compressed, recurved claw on the first digit. This clawed first digit was actually semi-opposable to the rest of the manual digits. The claw was proposed to have been used to hold prey while the jaws dismembered it or to tear open carcasses (Peyer et al., 2008; Weinbaum, 2013). This actually solidifies the comparison with carnivorous dinosaurs, which also used their forelimbs to hold prey.

(Interestingly, the pedal claws were also mediolaterally compressed (Peyer et al., 2008). They also look pointed and recurved. I wouldn’t be surprised if Postosuchus could even rake prey or rivals with its feet.) - You’re going to notice that the Postosuchus never really moves fast in this documentary. And while Postosuchus still didn’t exactly have cursorial limb proportions, it still would have needed some amount of speed (at least in bursts) to be able to ambush its prey. Its slow speed (along with that of the Placerias) plays into the narrative that these are sluggish creatures destined to be replaced by the swift, athletic dinosaurs one day.

- Peteinosaurus, an early pterosaur, is then featured as a supreme aerial hunter of insects. The previous aerial dominance of insects back in the Paleozoic is alluded to by Branagh, but now they have become the prey. This might actually be true (Bechly, 2004*).

It’s worth noting that Peteinosaurus is actually from Italy. They try to pass off its inclusion here as a visitor from “far and wide”, which…okay, I guess (this is Pangaea, after all). But as TV Tropes notes, some potential alternatives (one “known” from the time, the other not) could include Eudimorphodon (based on tooth and jaw fragments from Texas that may or may not be referable to the genus) or Caelestiventus (only discovered in 2018, so this one’s more of a “if we made WWD today” option).

*This was written by Günter Bechly, an anti-evolution paleontologist. It seems almost strange that he acknowledges evolution as a process in this article. Did he fall off afterwards? - I’m also skeptical of the idea of these early pterosaurs hunting and catching dragonflies. Dragonflies are notorious for being exceptionally agile fliers.

- The Postosuchus drinks at a waterfall. Btw, it’s not completely true that it’s the largest carnivore on Earth, or that the only creature she has to fear is another Postosuchus. Smilosuchus (a phytosaur) was a thing in this ecosystem.

- …Did I just hear a Torosaurus

- Anyway, it’s months into the dry season. Peteinosaurus is depicted bathing in a drying up river like a bird. A couple Coelophysis (including “our” female) try but fail to raid a cynodont burrow. The female Postosuchus has been recently gored in the thigh by a Placerias, and fails to make a meal. Not that the wound slows her down from her usual snail pace speed, though.

- I just noticed from the cynodont puppet that the upper canine seems to be exposed when the mouth is closed. I think they’re sufficiently short enough to have concealed by lips.

- The male goes out to hunt. One of his pups follows him to the burrow’s edge with the tender cynodont music playing in the background, only for a big mean poopy pants Coelophysis to snatch it.

Even in an episode centered on the underdog first dinosaurs, it’s the animals closest to us that are written to garner our sympathy the most. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, just an observation (a later documentary, Dinosaur Revolution, averts this completely). - The wounded female Postosuchus loses her territory to an invading male (and it’s really interesting hearing it make that prolonged Howie scream roar).

Now it’s time to address a criticism made of this scene. The male marks his new territory using water (in other words, he urinates). The criticism made was that archosaurs, including modern birds and crocodiles excrete their waste as solid uric acid. They don’t pee, and so an extinct archosaur shouldn’t either*.

Except they do. They totally do.

svpow.com/2016/01/28/yes-folks-birds-and-crocs-can-pee/

In fact, we now have what appears to be a trace fossil made from the jet impact of dinosaur urine hitting the sediment and being preserved (these were associated with theropod and ornithopod footprints) (Souto & Fernandes, 2015).

It is true that archosaurs produce much more of their nitrogenous waste in the form of solid uric acid than liquid urea, just as how we mammals do the reverse (much to my chagrin; some of the lab mice I work with piss A LOT in their cages, forcing me to change them damn near every day). But both compounds are indeed produced by both groups of animals, and so archosaurs can indeed still urinate.

*Michael J. Benton noted even back in 2001 that this can’t be known for certain. Although his statement that birds and crocodiles don’t urinate is erroneous (as I explained above), copious urination is the primitive condition for tetrapods, and may have been retained by some basal archosaurs (Benton, 2001). - The cynodont burrow situation becomes so bad that at nightfall, the parents are forced to eat their own young. This is the most fûcked up (from our perspective) thing the cynodonts will do in this episode, but it’s still made clear that it’s a necessary thing. After all, they can’t take their young with them. It’s either eat them and leave, or leave them to the dinosaurs. Again, the cynodonts, as our closest relatives in this episode, garner our sympathy (if through a sad moment this time around).

The dinosaurs continue to dig out the burrow in the morning, not knowing at first that the cynodonts have already left. But it’s gonna be alright, because a few minutes from now they’re going to get a much, much bigger meal. - ”The dinosaurs’ unique serrated teeth”

Huh? Lots more things than dinosaurs had/have serrated teeth. The Postosuchus in this episode has serrated teeth, for one.

Anyway, the female Coelophysis finds and tries to eat a lungfish in a cocoon in a dried up riverbed. The problem is other Coelophysis detect it too and leads to a skirmish. I’m especially a fan of the bird-like behavior they exhibit in this confrontation. They even have a deeper vocalization they make when angrier or under increased stress. - What was that “much, much bigger meal” I was talking about earlier? Oh yeah, the female Postosuchus has lost the use of her hindlimbs, and is on death’s door. A massive flock of Coelophysis surrounds her as she dies. And let me just say, her drooling, scarred animatronic face with blank eyes used to creep me out as a kid.

Although she just dies from the complications of her injury, the Postosuchus’ death is kind of sad to watch. This mighty huge apex predator being reduced to food to a bunch of scaly bird-like twinks is just…come on, that’s so unfair. - The last you see of the dicynodonts is them walking away from the screen in search of moisture and better feeding grounds. We see a Postosuchus’ cranium lying in the parched ground. The dinosaurs, by contrast, are said to have an advantage over all these creatures, on the grounds that they excrete very little water when they rid themselves of waste. But like I illustrated above, this is something that should be true of literally any archosaur, including things like the Postosuchus in this episode.

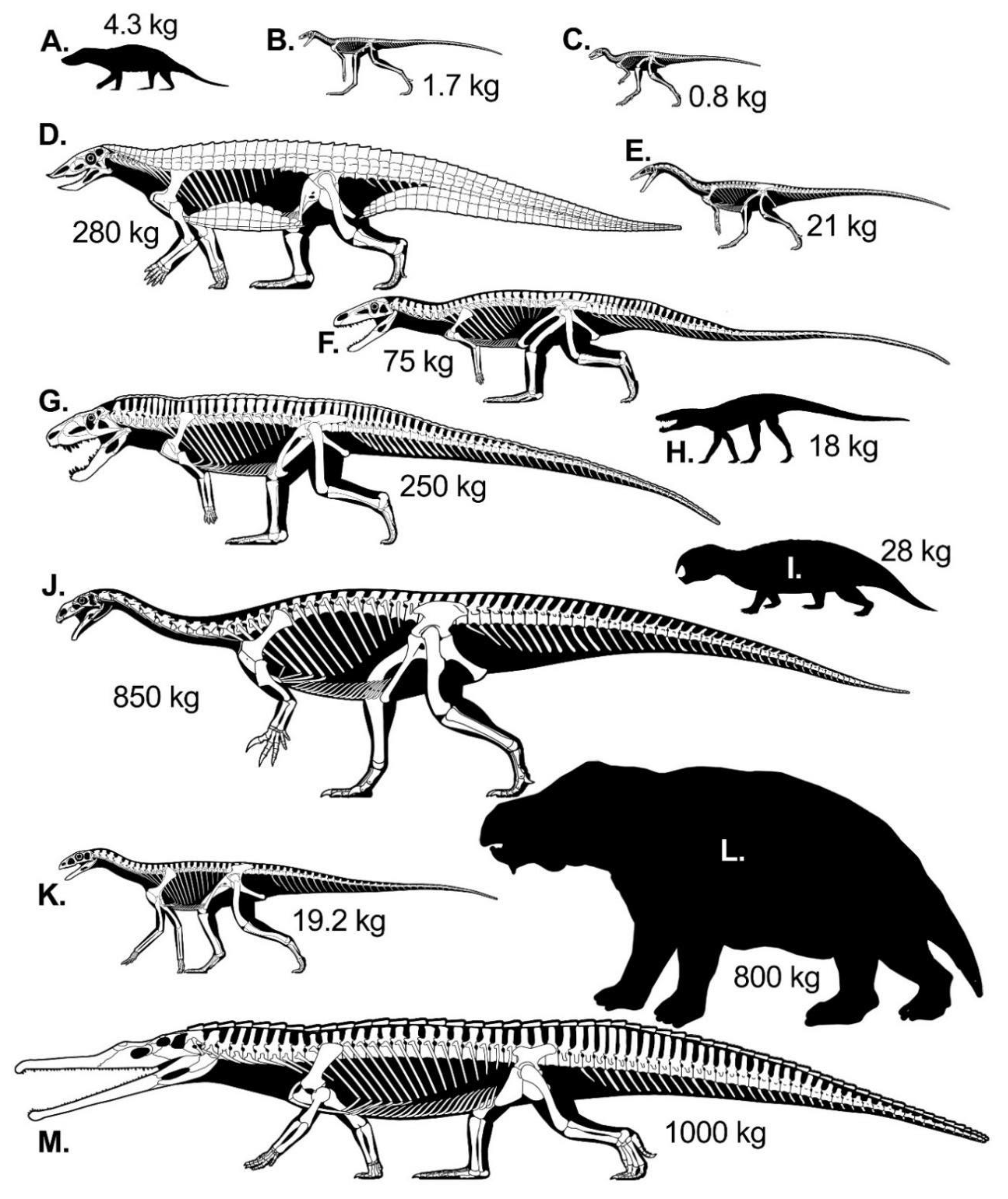

And IMO this is a perfect microcosm of the narrative of this episode: dinosaur supremacy. Even when the thing that supposedly makes dinosaurs “superior” is also shared with other animals. Turns out that pseudosuchians in the Triassic had more morphological disparity than did the dinosaurs of the time (Brusatte et al., 2008). Look at the kinds of forms they produced in the image below.

(One of these is a phytosaur, which may or may not be pseudosuchians proper. They’re recovered as either the earliest diverging pseudosuchians or the sister group to archosaurs (Jones & Butler, 2018).)

Even if a group of animals wasn’t doing the same kinds of things the dinosaurs (or archosaurs in general) were doing, that doesn’t make them “inferior”. The synapsids of the Triassic had virtually none of the neat stuff the archosaurs of the time are praised for having (bipedality, air sacs & pneumatic bones, wasting little water), but the dicynodonts lasted until the very end of the Triassic, even producing a form as massive as a large adult Plateosaurus. Mammals sensu lato had also evolved at around the same time as the dinosaurs; if hair, endothermy, parental care, milk, the neocortex, and the malleus-incus-stapes complex hadn’t evolved yet, you can bet that they were on their way.

Only very, very recently (as in, this month) did we find out that Triassic dinosaurs had more than just dumb luck going for them. It turns out that avemetatarsalians experimented with more locomotor modes than any other group of archosauromorph. Dinosaurs in particular consistently occupy the largest area of morphospace in limb proportions compared to any other group (Shipley et al., 2024). So to give credit where it’s due, the story of how the dinosaurs came to dominate is indeed probably more complicated than just a simple narrative of luck.

But imagine if someone made a documentary about how Mesozoic mammals had all these neat things going for them, and portrayed dinosaurs as evolutionary dead-ends destined to be replaced by the mammals*. That’s more or less what’s going on in this episode, only it’s the dinosaurs being put on a pedestal.

*Actually, as you’re going to see much later, the last episode of WWD sort of does that. - In the scene where a swarm of Coelophysis gather at a shrunken river, we see them resorting to cannibalism. This was based on fossil remains formerly thought to have been evidence of cannibalism in the genus, but it later turned out these Coelophysis specimens were eating pseudosuchians instead (Nesbitt et al., 2006). But honestly, I can hardly even consider this an “inaccuracy”. Cannibalism is by no means some extraordinary behavior limited to certain groups in nature (the paper I just cited “calls into question” the frequency of cannibalism in theropods; given all the evidence of theropod cannibalism that came out later, I can’t say I agree at all). Pretty much any carnivore that can process the flesh of its own kind will turn to cannibalism if necessary. Just look up “theropod cannibalism” on Google Scholar and look at all the results you get. The association of Coelophysis with cannibalism may have been based on examples that weren’t, but I’m not going to bat an eye at any depictions of it.

- The cynodonts have dug out a new burrow, and the male catches a baby Coelophysis. Years later people would make a big deal out of the discovery of a baby Psittacosaurus in the gut of a Repenomamus (which, as far as it being our first direct evidence of the behavior, the hype was justified). But in retrospect, stuff like that is something we should have expected from the get-go. The mammal lineage during the Mesozoic produced a lot of predators that would easily have been enough to prey on baby dinosaurs.

- The drought ends after 9 months, and the animals that we see have pulled through are the cynodonts and the dinosaurs. The female Coelophysis and many others survived, as have, wait for it…a herd of Plateosaurus.

These last minute animals are used to signify the dawn of the age of dinosaurs. While we now know Plateosaurus wasn’t quadrupedal (I guess it was being debated more at the time), it was indeed huge. Adults weighed anywhere from ~600-4,000 kg (Mallison, 2010). The low sounds they make are great, and their dominance at the waterfall helps to highlight how impressive these beasts are. The track (appropriately titled “Time of the Titans”) playing in the background as Branagh tells us “…the age of the dinosaurs has dawned” still give me chills to this day.

If nothing else, that’s a testament to how well WWD illustrates narratives. It will be another ~20 million years before many of the pseudosuchians, all of the phytosaurs, and all of the dicynodonts will be wiped out by the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event. And as I explained earlier, the dinosaurs weren’t inherently “better” than any of the other lifeforms living at this time. They wasted no time trying to get big and filling whatever niches they could (as exemplified by the Plateosaurus), but the “age of croc-thingies” still has some time. - I find myself a fan of how the credits are used to transition from the current episode to the next. I quite like the panoramic view of the Triassic landscape at dusk. Here, Branagh alludes to the T-J event (the real point at which the “age of dinosaurs” began), and we get a glimpse into the sauropods of the next episode. WWB did things a bit differently: the premise of the following episode was narrated while we got some bits of footage of it. While that is kind of cool, I’m not sure if I prefer that to just saving next episode’s content for actual air time.

I say all this as if two decades haven’t passed and that this doesn’t matter in the slightest anymore.

Final verdict:This review already took up eight and a half pages on my Pages document (not counting the verdict). That’s more than my review for Sabre Tooth (which took up a little over five). I can see now that it’s a mix of being an “ackchyually” nerd and correcting inaccuracies, correcting people “correcting” “inaccuracies”, and, *checks notes*, other stuff. New Blood certainly does its job at pushing a narrative: the Virgin dicynodonts and pseudosuchians vs the Chad dinosaurs. But we now know that this narrative isn’t really true. Yes, the dinosaurs actually did have some things going for them even during the Triassic. But they were just one part of a much larger radiation of reptiles that thrived in the Triassic, and they weren’t even the majority of it. The pseudosuchians alone were a “dynasty” (to borrow a word from Life on Our Planet) in their own right, and there was a lot more than just the likes of Postosuchus or Placerias roaming around Pangaea. To be fair, this show is called “Walking with Dinosaurs”. And if you’re going to be portraying dinosaurs in the Triassic, it probably does behoove you to portray them for what they are: “underdogs” that have some things going for them trying to survive in a world that’s not completely theirs (though, this doesn’t mean doing the other Triassic denizens dirty in the ways I described above). But then this raises another point: maybe it’s time we start portraying the Triassic’s fauna just as they are, not as part of some narrative where they are replaced by the dinosaurs (or at least, save that for the very end). A documentary where the Postosuchus can just be a Postosuchus, not some big mean poopy pants boogeyman (boogeybeast?) to early dinosaurs. Aside from that, it was still nice seeing the Triassic fauna. It was cool seeing early dinosaurs doing what they could in a world they didn’t yet dominate. It was cool to see Postosuchus hunt a Placerias (a formidable animal multiple times its size), even if both were slow as battles. Nice to see Placerias isn’t a total pushover (if off-screen). Nice to see the beginnings of mammals as we know them (even if we could still learn a thing or two on when some features evolved). So overall, while I probably have rose-tinted glasses on my eyes, I can’t bring myself to hate this episode (or any episode of WWD). If we had to improve on this episode nowadays, though, there’s a lot we could do.

|

|

|

|

Post by dinosauria101 on Feb 20, 2024 21:38:52 GMT 5

Time of the Titans: -We begin with a 25 ton Diplodocus laying her eggs at the edge of the forest. I would say the CGI model, the sound effects, and the eggs/egg tube (which look like practical effects) all look fabulous! -”She is one of a great family of dinosaurs called the sauropods, that dominate this period in Earth’s history. They are the largest animals that will ever walk the planet”. With Kenneth Branagh’s grandiose voice and the epic opera-esque Time of the Titans soundtrack, this is a very surreal introductory statement - and right after it we get a view of a Diplodocus from how we would see it if we stood underneath it and looked directly up, which drives it home perfectly. -Continuing the intro, we are in 152-million-year-old-Colorado. It’s been 70 million years since the dinosaurs appeared, Pangaea is breaking up, and much more rain lets there be forests where there were once deserts - allowing the dinosaurs to diversify, exemplified by some Othnielia (for which I like the model and sfx). -It is 3 months after the mother Diplodocus laid her eggs, and although hatching time…..they have been found by the bird-like egg thief Ornitholestes, who is stuffing his face with a baby Diplodocus. I think the blue crest on his snout looks awesome, inaccuracy be damned. Also, the destroyed eggshells strewn around look like practical effects again. Most appreciative in my opinion. -Right after this, our protagonist female Diplodocus (which Branagh appropriately describes as a sauropodlet) hatches from her buried egg along with her siblings* - straight under the gaze of the Ornitholestes, which is incredibly nerve-wracking until Branagh tells us the Ornitholestes is too busy eating to be chasing more sauropodlets (whew!) *It looks like they buried sauropodlet animatronics and had them come up for this scene! Awesome! -The sauropodlets (with great squeaking sfx) make a break for the thick forest once they are all hatched, in order to seek its shelter. Once they reach it, their attention turns to their next task. -“Between the trunks of huge redwood trees, the forest floor is covered in a dense layer of ferns. Beneath these, the sauropodlets immediately start their lifelong obsession with eating. Newly hatched they only weigh a few kilograms, but they will have to grow by 1 ton a year until they are adults. That’s an astonishing 2 to 3 kilograms a day”. There is no better word than obsession to describe the sauropod-food relationship, especially considering it gets to the point where few-kilogram animals have to grow 2 to 3 kilograms a day. Branagh nails his role as narrator again. -They used sauropodlet animatronics again here, to have them ‘eat’ real ferns. It looks and feels very authentic. But all is not quite so rosy: the Ornitholestes is back! To evade him, the sauropodlets must remain motionless and rely on their camouflage. -“It may have worked this time, but all too often the sharp eyed predator gets his meal”. Pretty ominous statement in the context of the sauropodlets. -After that we head out onto the prairie, to get glimpses of Stegosaurus (love both the sfx and CGI model here), Othnielia, and adult Diplodocus (which have incredibly majestic sfx), whose grazing keeps it as a prairie. Branagh states sauropods have the largest impact on their environment of all dinosaurs, and of all the different types, Diplodocus are the longest of them all. There is one hell of an epic soundtrack accompanying these scenes too! -More about Diplodocus in particular: Branagh tells us that they move in groups for protection (which as you will find out proves to be an important part of the plot later on in the episode), some of the older adults in said groups are over 40m long (which is breathtaking!), and that their tails have elegant whiplike ends for communication - which I would say are decidedly dance ribbon-esque in their elegance. We also learn about the various small animals that accompany so many giant animals. Insects stirred up by the Diplodocus attract hunting damselflies, which themselves are prey to pterosaur Anurognathus specialized to live on and around the sauropods (a most entertaining lifestyle if I do say so myself!) -To take it a step further, each Diplodocus drops over 1 ton of dung a day (which I used to think was a huge figure, but after some discussions on SpinoInWonderland’s Discord server it turns out Diplodocus dung has nothing on that of a certain group of animals LOL). Any member here and in that server should get the reference. Anyway, so much dung attracts dung beetles (looks like some live acted ones!), the descendants of which will be rolling the dung of the certain animal in question (double LOL). I appreciate that they showed us these dung beetles for context, as well as the reference to that certain group of funny animals. -One year later, the sauropodlets have grown substantially to over 3 meters long: our female feeds in a creche for safety and seeks moss growing on a moisture-dripping canyon wall (I adore the look of whatever real-world location this canyon was filmed in!). -What follows, in my opinion, is one of the most dramatic and impactful scenes in the whole episode. As the canyon runs down to the prairie, larger dinosaurs are also attracted - in this particular case, a 7 ton male Stegosaurus with both sfx and a soundtrack (The Smell of Prey) that are decidedly intimidating. -“He too is a herbivore, but very dangerous. The large plates on his back are primarily there for display. It is the meter-long spikes on his tail that make him so lethal. These he can wield with devastating effect, despite having a very small brain for his body size.” With Branagh’s tone of voice, the aforementioned sfx+soundtrack, and the Stegosaurus looking directly at the camera when Branagh starts to describe the spikes, this is where the intimidation really begins to ramp up. -The creche moves further down the canyon to get away from the Stegosaurus, but 2 Allosaurus (which I adore the coloring of!) are also drawn here by the smell of prey - and as they get closer to the creche, the decidedly ominous part of The Smell of Prey begins. -Once the creche notices, they amble away in fear (for which a panicky part of the soundtrack begins).....but not fast enough, one is taken down by an Allosaurus. (A minor complaint here is that I think there ought to be some visible wounds and bleeding at the area of the killing bite, but I can easily let it slide because it’s pretty one-off). They must amble past the Stegosaurus, who at first gets out of the way but then strikes one sauropodlet with its tail spikes, probably unintentionally as a result of being startled. Still, poor sauropodlets - although I do appreciate how the animators took the time to add convolutions to the struck sauropodlet. -With the soundtrack turning more dramatic and high-stakes, the second Allosaurus rushes past the first to get at the struck sauropodlet, only to be stopped by the defensive Stegosaurus who angrily bellows and color-flushes his plates with blood to make a frightening display. Confused and intimidated by the display (with a defiant roar), the Allosaurus is forced to back down - with appropriate ‘defeat’ music. -”Sauropodlets are small prey for the Allosaurus. These are the lions of the Jurassic, the top predators of their age”. So THAT’s where Allosaurus being the ‘lion of the Jurassic’ came from! -Back to the sauropodlets, they have now reached over half a ton, so are no longer as well hidden among the ferns as they used to be. And since they have grown, so have their teeth: as is demonstrated to us with real ferns and sauropodlet animatronics, they have become peg-shaped to efficiently strip ferns of their leaves. Then they encounter the skeleton of an adult that lies where it fell - its bones being too large for any forest animal to remove. Branagh’s statement that “The female sauropodlet can have little idea that in 10 years, she will be almost as large as this” is quite telling. -The Diplodocus skeleton in question looks like some very good practical effects. Amazing! However, at this point the creche have gotten too close to the edge of the forest and must move in deeper if they are to be safe. -Elsewhere, adult Diplodocus are pushing down trees to get at the ferns between them: this is how their grazing keeps the open prairie that way like alluded to earlier. It even looks like a real tree is being pushed down! Amazing. -This also ties into one reason they are so big: they can have long guts to digest the toughest Jurassic vegetation, aided by swallowed stones. And unsurprisingly, digesting so much vegetation means plenty of excess gas. -4 years later, an Anurognathus is seeking a Diplodocus to live on and around, and finds it in our female, who along with multiple creche members is well on her way to adulthood. She is over 12 meters long, weighs over 5 tons, and has begun to develop the spines and long whip-tail of an adult. Growing so large means that old predators in the forest are no longer a threat (a statement for which we see a hilariously futile aggression display from the Ornitholestes), but it also means that the forest is no longer appropriate habitat because there is neither sufficient food nor space between the trees. It is time for the creche to move out onto the plains and join a herd of adults. -”There is more room down by the banks of a river, but nature is about to take charge of these dinosaurs’ future”. Yep, Branagh said it. In this case it’s a huge forest fire to the south that reveals itself through the smell of smoke, and which the Diplodocus are perilously slow to flee from because their massive size and need to always have 3 legs on the ground prohibits them from doing more than ambling away. -I do like the manner in which the Diplodocus drink from the river, though. -That night the fire catches up to create a huge firestorm, for which it looks like real forest fires were filmed! One of the more epic practical effects of WWD, for sure. All this is aptly described by Branagh with a perfectly morose tone of voice and ‘scaredy’ soundtrack as “Above the sound of the blaze come the panicked cries of trapped dinosaurs. These Jurassic fires are rare but can be devastating”. –In the morning, we are shown an example of a dinosaur that perished in the fire with a singed Othnielia animatronic, which I would say does look quite authentic. Kenneth Branagh morosely tells us that there have only been 3 surviving members of the creche, now driven out onto the open plains and being exposed because they are not yet large enough to repel Allosaurus attacks (for this we see some Allosaurus that are watching them). -”To the young Diplodocus, the other dinosaurs here are unfamiliar. And huge”. Cue the appearance of everyone’s favorite Brachiosaurus, for which the music swells to incredible grandiosity. It completely dwarfs these Diplodocus! -We get a thorough description of these Brachiosaurus too: 13 meters high, able to effortlessly harvest leaves no other dinosaur can reach, and growing to over 70 tons on it, which in the WWD universe makes them the largest land animals that have ever existed. -All 3 of these are things I have come to appreciate about Time of the Titans after having viewed new documentaries for comparison. Prehistoric Planet and Life on our Planet were not, in my opinion, able to make clear the majestic giant size of their sauropods to this extent: they did not show the sauropods dwarfing everything else quite as obviously as the Brachiosaurus did to the Diplodocus, they did not give as much size context for their sauropods, their narrators were not as grandiose as Branagh, and nor was their sauropod music. This is also true of the older documentaries Dinosaur Revolution, Clash of the Dinosaurs (ick), and Dinosaur Planet (although they may be an inappropriate comparison because their saltasaurs look tiny even next to Diplodocus). In my opinion (which is an opinion you will hear more about when I review it, so stay tuned!), only Planet Dinosaur might have been able to match WWD in terms of giving their sauropods so much majesty. -Back to the young Diplodocus, they are in urgent need of the protection of an adult herd. We cut to the next morning where only 2 youngsters remain, and they are making calls for help adult Diplodocus are programmed to react to. And react they do! A herd of gigantic adults (for which we get a very majestic front view) have picked up the youngsters’ calls, and accepts them, at which point they are safe at last. -Five years later (which we start with more epic music), it is the mating season, and our female is old enough and large enough to finally reproduce. We see the male Diplodocus rocking back on their tails to impress potential mates, although occasionally fights - that is, rib-shattering, ground-shaking fights - do break out. The fight reminds me of Prehistoric Planet’s Dreadnoughtus fight, which likewise reminds me of another thing I appreciate about Time of the Titans: as you probably figured out from what I wrote a few points ago, Time of the Titans is very theme-adherent in making clear that this really is time of the TITANS. Meanwhile, Prehistoric Planet’s Dreadnoughtus segment was intended to be a total 180 to the classic ‘sauropod=gentle giant’ school of thought, and in my opinion their theme adherence to that was substantially poorer than here - even running into the ‘unreasonable suspension of disbelief’ category - because of the near-total lack of visible damage on the 2 Dreadnoughtus despite the fact that they were explicitly shown and stated to be stabbing and gouging one another with their hand spikes. -Anyway, a young male approaches our female, and they communicate with stamping+infrasound followed by body-rubbing. The mating itself is dangerous for the female since she must carry at least an extra 10 tons on her back - but as she has gotten older, her hip vertebrae have become fused to help her cope with the extra 10 tons. I think the sfx of the female and the shot of the mating pair are amazingly well done here! -Now for the ending. The mating season is over, the Diplodocus have calmed, and our female feeds on the edge of the herd - however, she is still not large enough to be immune from attack, and is unaware that 2 Allosaurus are watching her. To narrate this scene, Branagh’s voice turns more foreboding, which is a nice touch. -Once she has become distanced, the Allosaurus attack, and the music becomes appropriately fast and dramatic. One attacks her torso with a vicious snarl, although it is shaken off, while the other winds up attacking her head-on, for which she rears up and the music becomes more slow and tense. They engage in a standoff for some time until the huge tail of an adult Diplodocus knocks down the second Allosaurus, forces it to retreat, and saves the female. All throughout the Allosaurus are making those same vicious/fearsome snarls and growls I alluded to, which are actually slowed down chimpanzee screams(!) and in my opinion work quite well except for a single roar I think is a little too chimp-ish. –The female rejoins the herd with some visible deep wounds on her side, but Branagh thankfully states she will recover. This scene has 2 more things Time of the Titans makes me appreciate even more from having seen new documentaries: in this case it’s Prehistoric Planet. As those who read my reviews for it know, I found its lack of gore during hunting scenes to be very egregious, as did I find their excessive shying away from large-prey hunting (especially the skipped Tarbosaurus and sauropod hunt), hence I can appreciate this large-prey (sauropod) hunt with the appropriate gore even more. -”Diplodocus can live for a hundred years, and above a certain size they have no natural predators. Sauropods dominate the Late Jurassic, and it will be millions of years before new dinosaur herbivores evolve to replace them. With their passing, life will never again be this large”. With this closing statement we get views of the entire Diplodocus herd, and more epic opera-esque Time of the Titans theme. Overall Verdict:

I think this episode may be either my favorite or second favorite in all of WWD. Not only is there a substantial amount I can appreciate from having seen new documentaries for comparison, but out of all the episodes I think this one is best described as truly WALKING with dinosaurs, since we follow the female Diplodocus from the moment she hatches until the moment she is on the verge of growing up - as substantial and immersive as the storytelling of other WWD episodes is, Time of the Titans shines out. Additionally, the music is very much Walking with Dinosaurs-esque. It has often been described as being a Dinosaur Opera, and of all the episodes, I feel this one has the greatest percentage of opera-esque music - so in my opinion, if someone was unclear on what Dinosaur Opera meant, watching Time of the Titans would greatly enlighten them. So overall a most substantial and entertaining watch that is appreciative in hindsight for the things that make it special. And in fact such an entertaining depiction is what got me hooked onto sauropods when I was in the palaeocommunity: even now that I know better to be in it, the entertainment’s appeal hasn’t gone away any.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 20, 2024 23:14:59 GMT 5

Time of the Titans (Colorado, 152 million years ago): - This episode takes place 68 million years after the previous one. Think about it: that’s literally an entire Cenozoic’s worth of time plus a couple more million years. Lots of time that could have been explored.

In a way, it actually feels nice to cut right through the chase and show the dinosaurs all big and mighty after a whole episode showing them as mostly small underdogs. However, they could have done what WWB did and had an intermediate episode between small, big, and bigger. Dinosaurs from the early or middle Jurassic would have been perfect. - This mother Diplodocus is stated to weigh 25 tonnes. This is closer to the weight of D. hallorum than to D. carnegii. She also gives birth using a (disgusting) long fleshy ovipositor. This isn’t actually supported by any fossil evidence, and was based on turtles, which use a short ovipositor. The main concern here would be how an animal could lay eggs from such a great height without breaking them. Presently I don’t see a problem with them just squatting/crouching down.

Art by Mohamad Haghani. - This intro…rocks!!! It is my favorite out of any in the entire program, and probably my favorite in the entire Walking with series. The music, the narration, the vocalizations of the Diplodocus, and how their sheer size is conveyed (particularly in the ventral view of the wandering sauropods). Few, if any other sequences capture the size and majesty of the giant sauropods as well as the intro to "Time of the Titans". And these Diplodocus aren’t even close to the biggest sauropods ever! Also a nice way to start off from the ending of the previous episode with the giant Plateosaurus, showing how far the dinosaurs have come. *chef’s kisses

- After a nice brief intro to this green Jurassic ecosystem, we revisit the forested nesting grounds that the Diplodocus in the opening scene laid her eggs in. Some of them have been eaten by an Ornitholestes, a theropod said to be related to the ones that will evolve into birds (a process that, at this point, is already well under way).

The one biggest thing I can poke holes into with the Ornitholestes is the nasal crest. In his 1988 book Predatory Dinosaurs of the World, Greg Paul interpreted some broken part of bone near the external naris to have been part of a crest in life. It is now thought that this was simply due to crushing of the skull after death. The Ornitholestes also bears quills on its neck. If we were making this today, we’d probably go several steps further and give it a coat of feathers all over its body (similar to the reconstruction down below by Wikipedia user PaleoNeolitic). As a coelurosaur closer to maniraptoriforms than to tyrannosauroids, feathers are highly likely for this genus, even if they weren’t the pennaceous feathers we see in modern birds.

- I love how they made up the word “sauropodlet” for this documentary.

- The track playing in the background matches well with the sauropodlets waddling further into the forest as the Ornitholestes helplessly watches all these snacks on legs run free (because he’s too full; I get that feeling bro). It makes for a rather adorable, dare I say almost comical scene. I get that the tone is supposed to be one of urgency, but a part of me can’t take it too seriously (and I mean this in a good way).

- One of the important things to include in a sauropod coming-of-age story is their rapid growth. At least in terms of narration WWD illustrates it well.

- I’m pretty sure the 40 meter figure is exaggerated. I mean, true, we almost certainly don’t have the largest individuals of Diplodocus ever in our fossil collections, but none of the fossil remains we currently have belong to 40 meter long animals.

- Notice how Branagh calls the Diplodocus necks “stiff”. Notice, too, how the Diplodocus hold their necks horizontally and straight. The making of the Diplodocus models was influenced by computer models created by Kent Stevens and Michael Parrish, and subsequently published in a 1999 study. Supposedly, the “osteological neutral pose” (ONP) was a horizontal, straight neck posture, and the animal could not move its neck very high up (link->).

But there were two fundamental problems with this. First, they assumed that the zygapophyses (facets of bone that slide past each other when the neck moves) must overlap by at least 50% at any given time. Looking at modern animals, this doesn’t appear to be true. There are animals, like giraffes and ostriches, that can bend their necks such that there is almost no zygapophyseal overlap at all.

Second, modern animals don’t really habitually hold their necks in ONP. If anything, it appears that they tend to hold them in an anterodorsal position. In other words, on a sauropod it would look rather erect (Taylor et al., 2009).

- Diplodocus is said to use its tail for communication. This is a hypothesis for the whip-like end of diplodocid tails, and the idea is that they would have been able to move fast enough to make a loud cracking noise. However, WWD doesn’t specify exactly *how* the tail would be used for communication, so maybe they could also mean visual communication? I don’t know if that idea makes sense.

Recent biomechanical studies suggest the tail whip would not have been able to withstand nearly the amount of stress to survive supersonic speeds (Conti et al., 2022). By no means does this rule out certain functions (esp. use as a weapon), although I don’t know how fast the tail needs to move to make the sounds necessary for communication. - I just love the way the Diplodocus call echoes across the distance.

- Anurognathus is depicted as a specialist in living off the backs (literally!) of Diplodocus. It feeds (on insects), fights, breeds, and even poops (as one individual does on-screen much to our delight) on Diplodocus for its whole life.

It wasn’t until nearly a decade later that we finally started to understand what Anurognathus actually looked like (Bennett, 2007). It had a short skull with a broad, blunt snout, ENORMOUS eyes*, and thumbtack-like teeth for feeding on insects (so WWD at least got that right). There’s a reason we call it “frog jaw”.

Reconstruction by Jaime A. Headden.

*(In fact, look at this Anurognathus puppet-> used for WWD. You see where the eye is placed? That’s actually where the jaw muscles ran through. You see that big-ass hole in front of where the eye is? That’s where the eye ACTUALLY was. Yes, its eyes were THAT FÛCKING ENORMOUS.)

Suffice to say, the WWD model doesn’t look anything like this. And with its enormous eyes, plus skull and dental morphology matching those of nocturnal or crepuscular insectivores (that hunt on the wing) (Clark & Hone, 2023), the idea that it was living off of the backs of Diplodocus seems unlikely. This is a pretty stark case of Science Marches On. - The reviewer I linked to in my previous review made time to critique the inclusion of dung beetles feasting on Diplodocus poo. His point was that while Scarabaeinae did indeed first appear in the Mesozoic (something further supported by a subsequent study; Philips & Pretorious, 2006), their diversification is tied more to Cenozoic mammal radiation (Davis et al., 2002). He pointed out that dung beetles were actually rare during the Mesozoic, and that there’s evidence that instead, an extinct family of cockroaches (Blattulidae) were cleaning up after dinosaurs instead. From the little I found, this indeed seems to be true (Vršanský et al., 2013).

But then again, rare doesn’t mean nonexistent. As such, there’s technically nothing wrong with depicting dung beetles feeding on dinosaur feces, it just probably wasn’t the most common thing (not compared to these blattulids doing it, at least). Furthermore, WWD only says that the dung beetles started out in the age of dinosaurs, which is true. So to be quite honest, I don’t have a problem with this. - Timeskip to a year later. Briefly we’re treated to “a dinosaurs’ dawn chorus” filling the air. This just made me wish to hear such a thing. What I wouldn’t give to hear dinosaurs bellowing and crying over a steamy redwood forest in the morning…

- Although we see a pair of Stegosaurus before this, we’re only truly introduced to the animal in the lush wet canyon (btw its vocalizations are one of my favorites out of any Stegosaurus depiction, along with the ones from When Dinosaurs Roamed America). Although it’s a herbivore, its introduction isn’t exactly a comforting one. Not with the background music and Branagh’s explanation of how dangerous it is. In my opinion, this sets a perfect tone for “herbivore=/=friendly”. You almost feel like something bad is going to happen with it soon…

- It gets worse when the lion of the Jurassic shows up: two Allosaurus. The music ups in intensity, and now the sauropodlets are stuck between a rock (or rather, two) and a hard place. One sauropodlet is taken by an Allosaurus, while another is cut down by the not-so-jolly Stegosaurus (what’d I tell you?). It’s almost a miracle more don’t die.

- Actually, it really is now that I think about it. Where was that second Allosaurus as the sauropodlets were fleeing the canyon? There’s no discernible reason it couldn’t keep up with its partner. Was it wearing invisible shoes that it needed to tie or something?

Whatever the reason, there seem to be no sauropodlets left for it to make a meal out of and it’s forced to try its hand with the Stegosaurus. It (rather understandably) only takes an intimidating display on the Stegosaurus’ part for the Allosaurus to give up and mooch off of its partner’s kill.

“What, is a Stegosaurus too tough for you?”

“I’m pretty sure it’s too tough for anyone.”

“Skill issue. I saw Frank take one down last week.” - We need to discuss the plates of the Stegosaurus. Here it’s depicted flushing blood into its plates, making them appear red in order to appear more imposing. The problem is that stegosaur dorsal plates were covered in keratin in life (Christiansen & Tschopp, 2010), and there’s no keratin structure known where it changes color from blood flow.

- God, I love the phrase “lion of the Jurassic”.

- Wait, the ‘podlets are half a ton now? Is that how big they are during the canyon attack? I…did not get that impression. They didn’t look half a ton.

- It is true that Diplodocus reached sexual maturity by a decade. That doesn’t mean full size, though.

- One thing WWD does a really good job with is conveying the sheer power and weight of the sauropods. When a Diplodocus fells a tree, the deep thud of the tree slamming the ground, followed immediately by the equally impressive boom of the sauropod falling back on its front feet, are real ear candy to me. Fitting, too, that this scene is supposed to explain to the viewer how sauropods are these gigantic ecosystem engineers that clear the forest. They’re clearly inspired by elephants, only they’re bigger.

- Branagh mentions that the sauropods swallow stones to help digest food. Back then it was thought that sauropods used gastroliths to help break down food in their gut, based on stones that seem to have been found inside the guts of sauropod skeletons.

After WWD aired, though, paleontologists took a closer look at this idea and the evidence behind it. In 2011, a field test gave domestic ostriches (living dinosaurs that largely eat plants) three different rock types of different hardness to swallow (quartz was the hardest, followed by granite and limestone, respectively). It was found that, depending on how hard they were, the rocks became considerably abraded from their time spent in the stomach acid of the ostriches. The experimental gastroliths (nor those from any other extant birds) had the highly polished, asymmetrical shape of supposed sauropod gastroliths either. Based on the volume of gastroliths in the ostriches, it was estimated that a 50 tonne sauropod would need 500 kg of gastroliths. This is a lot more than what is actually seen in sauropods that supposedly preserve gastroliths.

So from the looks of it, it seems sauropods didn’t actually use gastroliths to digest food. So what did sauropods do? Well…it looks like they just swallowed and let their GI tracts break food down. The stomach and later the hindgut would break it down, and then bacteria in the hindgut and caecum would ferment it. As long as there’s enough food in the gut at any given time, the sauropod will have something breaking down and releasing nutrients inside of it. In effect, you could think of a sauropod’s GI tract like a compost bin (Hallett & Wedel, 2016). - WWD featured farting dinosaurs and I did not pay attention to that in my childhood…

- Four years later, the female sauropodlet we’ve been sorta, kinda following (I mean, we HAVE been following her, but she just barely qualifies as a main character) is now as long as a T. rex and as heavy as a bull elephant. The small predators that she and her creche once had to hide from, like Ornitholestes, are now perturbed by their presence. That said, the sauropods are getting too big for the forest and will soon have to move out into the plains. Eventually they do…

…but not before a forest fire breaks out by night. The cries of the dinosaurs trapped in the flames sell the terror of the scene, especially the ghost-like calls of sauropods and the alarm-like call of another creature. We even get the charred corpse of a small ornithopod: imagine how much more crushing it would have been had they shown us one of the sauropods from the creche. Speaking of them, only three survive the forest fire. - Although, does Diplodocus really need at least three legs on the ground at all times? I believe elephants can get away with having two on the ground while ambling. Why should a 5 tonne immature Diplodocus do any worse? And how big would the forest need to be that some ambling Diplodocus can’t get out before the fire consumes the forest by night?

- It’s interesting how Branagh notes that the young Diplodocus still aren’t large enough to be immune from Allosaurus predation. Adult Allosaurus fragility typically weighed from ~1.7-2.3 tonnes, making them considerably smaller than a 5 tonne Diplodocus. This suggests the WWD team believed an Allosaurus could take prey much larger than itself, something corroborated by the end of this episode. That is something I’m glad to see reflected.

- The Brachiosaurus has this dramatic, epic theme, fitting for an unfamiliar dinosaur that towers over these Diplodocus. But “largest animal that ever existed”? 70 tons? No.

- Later the creche is down to two. No explanation given as to what happened to the third one. It just up and disappeared. While that can be seen as hilarious, it’s also genius for the purposes of WWD. It helps create the illusion that someone went back in time and filmed all of this. A film crew isn’t going to be able to capture or observe everything with an animal or group thereof that they follow, so they’re completely in the dark on what happens in between their shot footage. This then translates over into a limited narrator. Who knows what happened to that third Diplodocus? Maybe it fell down and broke a leg. Maybe it got picked off by an Allosaurus. Maybe it wandered off, got lost, and ended up finding a different herd.

- But eventually, the calls the youngsters make pay off and an adult herd finds and accepts them. “Safe, at last”…

*deeply breathes in Allosaurus* - Five more years pass, meaning a decade has passed since the female and that one other surviving creche member (assuming the latter is still alive) hatched. She becomes mature enough to mate which, as I said earlier, is indeed accurate.

We get to see a brief fight between two males, which I think is neat. They shoulder each other, and Branagh notes that the forces at work here can shatter ribs. Sauropods are often seen as “weaponless” animals. Aside from the fact that their clawed column-like limbs and tails (maybe even their necks) could have served as weapons, here’s the thing: when you weigh multiple tons, you don’t need specialized weapons to severely injure another animal. Just shoulder/body slamming something in the ribs can break them and possibly splinter them (this can drive them through internal organs, and that can be fatal). The fact that these animals are so massive makes this a very likely scenario. Elephants today sometimes bear broken ribs that they received from fighting other elephants. Imagine sauropods double their size or much, much more. - It’s interesting how the mating doesn’t take long. I remember reading how some modern reptiles will mate and it only lasts a few seconds or so.

- Ah yes, the origin of this meme.

- Btw no, I don’t think an adult Allosaurus could/would leap like that.

- The Allosaurus is defeated by a tail swat from a larger Diplodocus that catches it off guard. Afterwards, Branagh tells us how Diplodocus can live for a century (pretty sure this is outdated), how it will be millions of years before the sauropods will be replaced by other herbivorous dinosaurs (not really true), and how life will never again be this large (which remains true as long as you’re talking about land animals). This idea that the sauropods will go into decline at around/following the Late Jurassic is further alluded to during the end credits of this episode. According to Branagh, the lowland prairies the sauropods inhabited became flooded due to rising sea levels.

I get that this idea that sauropods faded away after the Late Jurassic was a somewhat prominent idea at the time (even though we’re all now fully aware that not only did sauropods live until the end of the Cretaceous, but they were on literally every continent until then), but…where did this idea that their habitat was inundated by sea levels come from? - One more small thing: just before the show cuts to the credits, we hear one last Diplodocus call, sounding kind of like it came from the distance. I love that little detail.