|

|

Post by Grey on Jul 16, 2018 2:16:29 GMT 5

No need to enter the mind, the way the animal collect flesh on the larger prey items without prolonged attack is enough to sustain itself. This is what have been observed FKW to do. Large sharks have not been observed doing so, though I need to see this tiger shark case.

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Jul 16, 2018 4:46:42 GMT 5

I've heard of tiger sharks occasionally attacking injured/sick whales, but the "intent" seems to be both to feed and to kill. In other words, the sharks aren't just taking a mouthful and going away content, they come back again and again to feed which also results in expediting the whale's death, thus making it even more easy to feed. I think groups of grey reef sharks (or maybe its oceanic whitetips) have been recorded predating on juvenile whales in a similar manner, chasing the animal and attacking/feeding until the animal is dead, and then continuing to feed.

I can't call such behavior pure fleshing grazing; it seems more like a prolonged predatory attack. You can even see similar behavior in land carnivores. Occasionally, a lion might rip off part of a large prey animal like a zebra or cape buffalo while the rest of the pride is pulling the animal down. The lion may leave the attack to feast on the part it procured on its own and not rejoin the fight, but you wouldn't call that lion a flesh grazer.

Of course, this type of behavior may have been what motivated the attacker in the Kallal fossilized rib. It may have been an already sick/injured whale that a large group of sharks and/or other predators was attacking and this fossilized bite was but one of many feeding bites. What might make this exact scenario somewhat less likely is that the whale apparently lived for several weeks after the bite, which doesn't suggest a terminally ill whale at the time of the fossilized bite to the ribs. Of course, perhaps prehistoric sharks (and maybe even modern days sharks) sometimes follow injured whales for weeks at a time, taking bites at their leisure until the whale finally succumbs from its injuries. I don't think the modern day accounts of sharks killing whales takes anywhere near several weeks, but then again the behavior has only been rarely observed.

Maybe juvenile mega-toothed sharks, being hard-wired to attack very large cetacean prey far more than modern day sharks, were more aggressive than modern day sharks in either solitary attacks on larger whales, or in forming groups and engaging whales in a group attack that would injure and finally kill the whale. We'll never know for sure just how it happened.

|

|

|

|

Post by prehistorican on Jul 16, 2018 7:10:26 GMT 5

Yep, and also the 15 dusky sharks killing and chasing a humpback whale calf. www.researchgate.net/publication/276500821_First_observations_of_dusky_sharks_Carcharhinus_obscurus_attacking_a_humpback_whale_Megaptera_novaeangliae_calfSharks can violently frenzy on live prey and take on prey far larger than a single shark. The green lanternshark known to only grow up to 26cm and less than a kilogram at adult weight can take on squid and ocotpus so large that they would have to distend their jaws greatly to swallow the relatively massive beaks (probably the size of their heads meaning probably a 2m total length squid or similar sized ocotpus). They seem to swiftly slice off flesh from the cephalopods. This swarm/frenzy attack method was used by the dusky sharks but on the humpback calf. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Jul 16, 2018 22:03:20 GMT 5

www.youtube.com/watch?v=l4xZC5xuRJAYes, large sharks have been observed doing this. More clearly so than Pseudorca, considering this shark is actually seen feeding, while the Pseudorca you consider to have been "flesh-grazing" have not (and both constitute prolonged attacks). Without reading it’s thoughts we can not be sure whether that shark had some notion of killing the whale, or whether it just wanted to feed on it without doing so, which it did (again, if that isn’t applying overly "human" concepts of life and death, which tiger sharks might not even have to begin with). So is that flesh-grazing or predation to you? Same story with Pseudorca attacking Physeter (Note that Palacios & Mate 1996 do discuss the behaviour they observed as a possible case of predation, but "flesh-grazing" is neither mentioned nor discussed at all. Here too, we do not know whether the "intent" was to kill or to parasitise, rendering the distinction meaningless). And then we have the Kallal et al. whale rib, which is clearly from a whale that survived for a significant span of time after the attack, otherwise it wouldn’t show such a degree of bone remodeling. That shark bite clearly wasn’t a direct cause of the whale’s death, whether or not it contributed. So if you don’t consider "flesh-grazing" to be predation, that’s no evidence of predation. Seriousness of the injury is the point though, it is conceivable that feeding behaviour from such an attacker could have caused fatal damage to the whale. It is conceivable that feeding behaviour of false killer whales may be fatal to sperm whales. It is conceivable that a tiger shark feeding on a blue whale could be fatal for the blue whale. And apparently the same goes for groups of dusky sharks feeding on whale calves. The same is not true for cookie-cutter sharks. The former four are predation of varying outcome, because they are at least potentially fatal to the fed-upon party, the latter is parasitism because it is not. Saying such behaviour is not observed in extant sharks is literally saying that there are no known cases of prey items surviving a shark attack. Since the only objective criterium to differentiate is whether the prey survives, failed predation and flesh-grazing are often just the same thing.

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Jul 21, 2018 9:05:04 GMT 5

.

Yes, that's what I were referring to in my last post; I had thought it was probably oceanic whitetips, but couldn't find the article. Good find Prehistorican. Dusky sharks! Who would've thunk? I mean, they are a good-sized shark but not really known as big game hunters to my knowledge. Just goes to show how little we really know of the oceanic ecosystem.

|

|

|

|

Post by prehistorican on Jul 22, 2018 1:32:01 GMT 5

elosha:

Yes dusky sharks are actually more of a generalist and not robust mammalian killing shark species which made it quite interesting for me. Each dusky shark was estimated at 2-3m long. So an average of 2.5m and almost 94kgs. They say that 10-20 sharks attacked the whale, so an average of 15 sharks seems reasonable. It seems this calf was a newborn maybe 2 weeks old. On the Wikipedia page it states that a calf at birth is almost 1633kgs. If we go by the averages, then a feeding frenzy of 15 dusky sharks each 2.5m and 94kgs each (total weight of 1,410kgs) killed a 1600+kgs humpback newborn/calf. The attack also went on for 6.5 hours long, the length and extertion from the chase eventually killing the whale.

On fishbase it states the dusky shark:

"Feeds on bottom and pelagic bony fish, sharks, skates, rays, cephalopods, gastropods, crustaceans, sometimes mammalian carrion and inorganic objects".

Even the Wikipedia page gives very heavy emphasis on the diverse piscivorous diet of this shark, only the largest specimens eating sea turtles and carrion form marine mammals mostly. However the attacking specimens are nowhere near the 4m and 300+kg range, and seem quite average.

The absolute gargantuan size difference between the individual shark and prey item seems quite ridiculously huge.

In the scientific paper the authors stated:

"Dusky sharks have smaller bite widths (usually less than 30 cm) than these other potential shark predators as well as smaller, more numerous overlapping teeth with finer serrations (Long and Jones 1996). As a result, the bites observed were small and clean cut with almost no tissue removal and consisted pre- dominantly of rakes and scrapes, which are typical of carch- arhinid sharks (Long and Jones 1996). This is not surprising since mammalian remains are rarely found in this species, which feeds primarily on bony fish and other elasmobranchs".

here is the paper:https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alison_Kock/publication/276500821_First_observations_of_dusky_sharks_Carcharhinus_obscurus_attacking_a_humpback_whale_Megaptera_novaeangliae_calf/links/5a3b4b97a6fdcc7ffe649220/First-observations-of-dusky-sharks-Carcharhinus-obscurus-attacking-a-humpback-whale-Megaptera-novaeangliae-calf.pdf?origin=publication_detail

Hypothetically if the duskies were to be replaced with scaled down white sharks, I believe they would do a lot of damage. Much more than observed here.

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Aug 4, 2018 3:02:48 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Aug 4, 2018 3:07:04 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Aug 22, 2018 20:15:03 GMT 5

Recent and very interesting article in July 2018 about ongoing research at the Smithsonian regarding Megalodon bite marks on fossil whales, and what it can tell us about the size of the prey and whether increased size of whales contributed to Megalodon's extinction. Research is ongoing with no conclusions as of yet. Here are the pics followed by the article. Link is ocean.si.edu/what-megalodon-left-behind  The largest shark ever to exist on this planet, Carcharocles megalodon, could grow to be 60 feet (18 meters) in length and weigh over 120,000 pounds (60 tons). Five rows of fearsome teeth—some over 7 inches long—gave rise to the name Megalodon, meaning “big tooth.” This massive animal, whose jaws were large enough to eat a modern-day adult rhino, most likely preyed on whales. What were whales to do in the face of such a gigantic predator? Meghan Balk, a Peter Buck Fellow at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, wants to test the hypothesis that small-bodied prey species evolve larger body sizes to escape predation. The larger the prey animal, the more energy it takes for the predator to attack and the risk of being injured itself becomes greater. Since the smaller prey animals were eaten by far bigger predators, prey lineages may have evolved to become larger. For Balk and her summer intern, Jazmin Jones, studying Megalodon and its prey is ideal for testing this hypothesis since the giant shark went extinct about 2.6 million years ago and scientists think it was probably due to a lack of available prey. If the prey species the shark was accustomed to eating got bigger—too big to attack even—that could explain the shark’s demise. Before one can look at prey sizes over time, you first have to know what the prey species are. This summer, Jones was tasked with examining marine vertebrate fossils in the NMNH collection to identify who was being bitten. Megalodon first patrolled the water during the middle Miocene, around 14 million years ago, but was extinct by the end of the Pliocene, which ended about 2.6 million years ago. So, Jones photographed and documented all the marine fossil bones from the Miocene and the Pliocene geological epochs for evidence of shark bites. For three weeks, Jones inspected bones—around 100 in total—to look for marks and then cataloged the marks according to a classification system of six groups. The marks ranged from a fully embedded tooth to a subtle scratch mark. The embedded teeth were particularly exciting as Jones only found about four throughout the course of the three weeks, but even without such a find the process was fun. “It’s very exciting because each bone is unique,” said Jones. “It has its own unique set of scratches and patterns. Sometimes I come across strange things…it’s like solving a mystery because I can infer and possibly create a story to explain some marks.” It can be quite difficult to determine the predator without the help of an embedded tooth—serrated marks may indicate a Megalodon bite since the colossal shark had ridges in its teeth. It is also difficult to identify the species associated with the bone, especially when only a fragment of bone remains. But even placing a bone into a particular group (such as the Mysticetes, the baleen whales, and Odontocetes, toothed whales) can be helpful. Both Mysticetes and Odotocetes were present during the Miocene and Pliocene and were likely preyed upon by Megalodon. Jones recorded every bit of information, from the bone size to descriptions of the various marks, in order to hopefully make a positive future ID of both predator and prey species. At the end of Jones’ three weeks, there was a small dent in the task of cataloging the almost 4,000 NMNH marine bones from the time when Megalodon roamed the oceans. Once the prey species are known, the work of estimating body mass of the potential prey can begin. It will take time to definitively answer the question of whether Megalodon’s prey evolved to get bigger to avoid predation by way of the shark’s jaws. A close look at each bone can help put together pieces to tell a story, and eventually show the full picture of past predation. July 2018 |

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Aug 29, 2018 21:30:52 GMT 5

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Sept 4, 2018 23:42:14 GMT 5

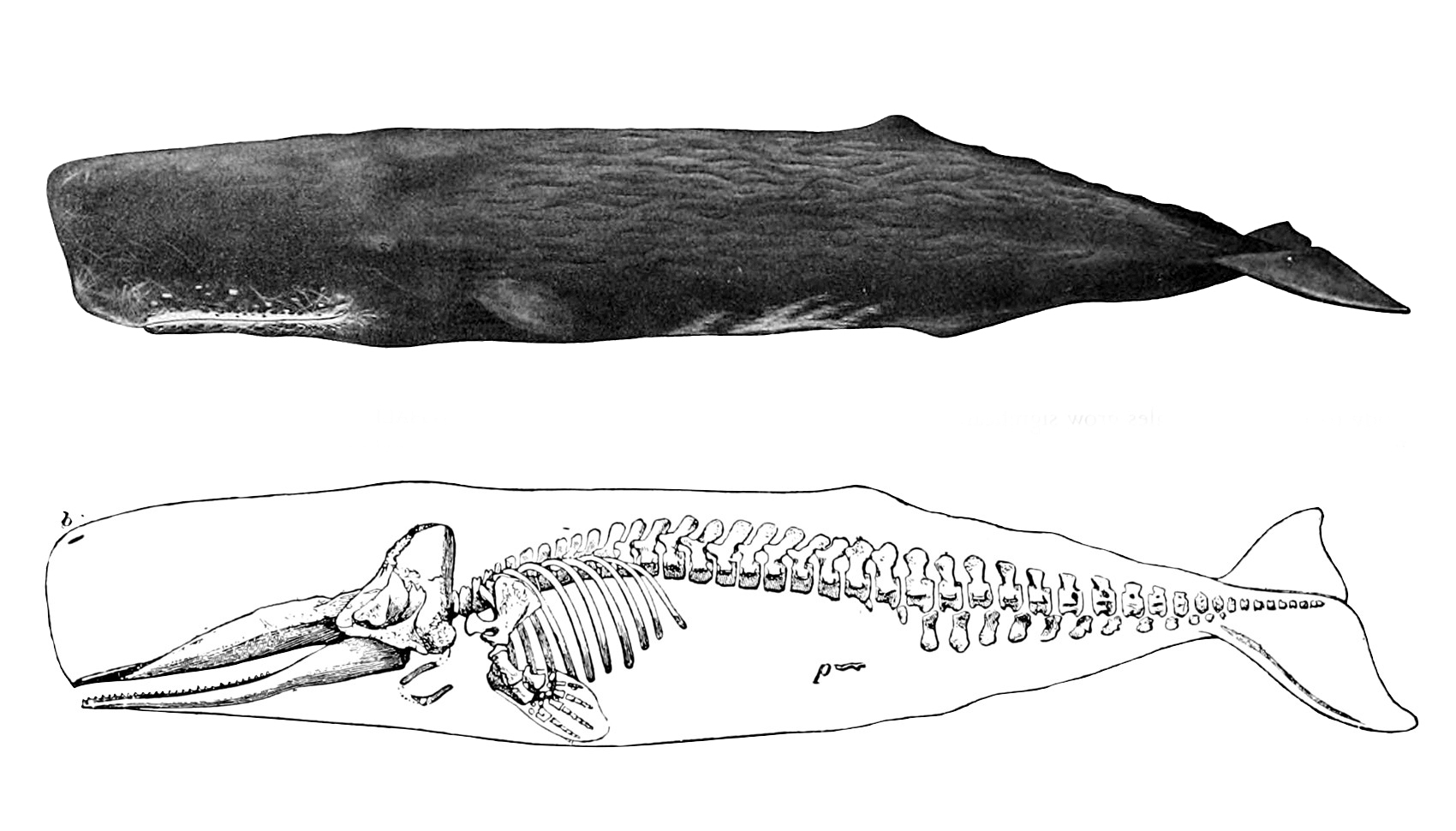

^Interesting. I assume this is the one you are referring to, which is posted back on page 3 of this thread. However, there are a number of other quite large bitten centra posted on this thread from paleodirect, so let me know if you are referring to a different fossil from their website. I've posted all the shark bitten fossils I could locate from their site.  Is your contact an expert in the field, or simply a knowledgeable fossil collector? And either way, what makes him believe this is a caudal vertebral centra? Is there some structural shape difference that looks more like a centra from the tail region? I've posted a number of examples of bitten centra that are claimed to be from the caudal area, but I'm not knowledgeable enough to know the difference on sight alone. Also, is there any reason he thinks this came from a physeterid like Livyatan, as opposed to a baleen whale? Are there noticeable differences between their vertebral structures? About that vertebra again. Today I ran inti the unexpexted opportunity to have a detailed look from multiple angles at a complete, mounted sperm whale skeleton at the Manchester Museum. So now I've actually got an idea what the haemal facets should look like, and also thee ventral surface of the other centra. The interesting thing is that not only does this vertebra definitely not have a haemal arch facet (which is formed by the posterior end of two keels on the ventral surface), i.e. its not a caudal, it also doesn't have the single, sharp median keel that seems to characterise lumbars. This vertebra actually looks most like a thoracic in terms of the round ventral surface of the centrum. As the neural spine and zygapophyses are missing, I can't confirm that asessment based on those features, but what's preserved of the neural arch and the bases of the transverse processes wouldn't be at odds with that. If this really is a thoracic, that would most likely indicate either very intense feeding on the carcass, in order to have left toothmarks on the ventral surface of a centrum that in life would have been inside the ribcage, or feeding on a scavenged carcass that was already falling apart (but it is my understanding that such a carcass would have sunken to the ocean floor, where it's unlikely a pelagic shark would have fed on it) |

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Sept 6, 2018 10:43:16 GMT 5

^Very interesting. If this is indeed a thoracic, I would presume that this relatively large centra was not the largest in the skeleton, since cetacean's lumbar and some caudual vertebrae are noticeably larger than the thoracic vertebrae, as seen here for the sperm whale and a baleen whale.   I would like to compare this possible thoracic vertebrae to a full grown modern male sperm whale to get a possible size comparison. However, I think the Manchester Museum specimen you saw was a relatively young male sperm whale and not full grown. Do you have any thoughts as to the size of this particular whale, under the assumption that you are correct that this was a thoracic vertebrae? I had made a rough estimate awhile back that this particular fossil might indicate a sperm whale around 40 feet long, given the size of the vertebrae and the evidence suggesting that prehistoric sperm whales - while large - were smaller than today's counterparts. Given the relatively common mega-toothed bite marks on fossil cetacean ribs, those bones seem like a regular target for them. And since those fossil ribs often show great damage or even being bitten in half, I think an adult Megalodon (or perhaps a large C. chubutensis) could readily bite through even a large whale's carcass's blubber and rib cage and get to thoracic vertebrae. OF course, the unanswered and perhaps unknowable question is still whether this was predation or scavenging. I do agree with you that it would have probably been a relatively fresh carcass even if it was a scavenging event. |

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Sept 6, 2018 23:50:32 GMT 5

I just rechecked today and compared the lateral view, and I think I must correct myself but that we can constrain its position further than that. The most likely position actually seems to be the last dorsal or one of the first two lumbars, behind which the centra develop their marked ventral keels. More anterior dorsals have dorsoventrally thicker and more dorsally located transverse processes than seem to have been present in this specimen.

You are right as to these not being the biggest vertebrae in the column. As for a size estimate, I'd be extremely hesitant to makee one while knowing neither the measurements of the specimen we are trying to estimate, nor those of complete Physeter individuals. Just eyeballing, the size might or might not be consistent with the skeleton I saw (either female or young male, at least the skull seems to be 2-2.5m and quite small compared to the body by male standards, but I'm terrible at judging the total length of the skeleton accurately). But that guess may turn out to be completely wrong.

So by all means, if you have measurements of this vertebra and comparative measurements of a complete sperm whale, have a go at it.

What are those data on sperm whale size evolution you are referring to? I've never seen a published description of any fossil Physeter individual to be honest.

I do have my doubts whether a megalodon could really bite completely through the thorax of a whale in the way required to cause these scratches on the ventral side of the vertebra. That's not a question of cutting through some blubber and ribs, it would literally have to go through the whole depth of the ribcage, actually not cutting across the ribs but in parallel with them, so the ribst would quite literally get stuck in its jaws vertically. Of course this also depends on the size of the whale, which we can't really tell at the moment, and that of the shark, which from this alone we'll never be able to tell at all. But I think its more likely that these are feeding traces, caused at some point after multiple bites.

|

|

|

|

Post by elosha11 on Sept 7, 2018 5:02:45 GMT 5

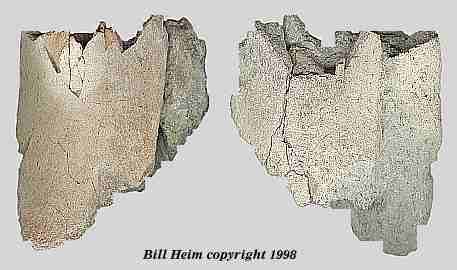

Here's some more pictures of the vertebrae. It's really quite large. Looking at the Manchester Museum specimen online, I doubted it was very large (one website said it was a young/juvenile male) and presumed it had substantially smaller centra than the one we're discussing. Pics are from the wayback archive machine. web.archive.org/web/20110722071922/http://www.paleodirect.com/pgset2/wh006.htm   I've seen some sources informally state prehistoric sperm whales may have been smaller. One associated fossil jawbone, flipper and teeth found in California was estimated as a 40 footer and the article quoted a director of some type of paleontology program as stating modern sperm whales are larger, reaching up to 60. Here's the article link. www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/landfill-surprises-scientists-12-million-year-old-whale-fossils-180959566/. However, I don't think this proposition has ever been put to rigorous, formal analysis. Obviously, there's the general trend that whales have seemed to grow larger over the course of their evolution. Yes, I wasn't trying to imply that a Meg bit through this in one bite. But I'm not sure it couldn't be done in multiple bites. A large Meg likely would bite the carcass multiple times along with vigorous lateral shaking, perhaps breaking the ribs in a more horizontal direction, and opening up the body for attacks deeper into the cavity. In this thread, I've compiled at least two or three examples of the shark biting in half fairly sizable vertebrae (obviously not as big as this one) and also shattering or biting through whale ribs, iike this from Bill Heim's elasmo.com website.  Here' Heim's description. |

|

|

|

Post by Grey on Sept 7, 2018 6:40:04 GMT 5

|

|