Post by creature386 on Apr 10, 2014 22:05:42 GMT 5

Baurusuchus salgadoensis

©Carvalho et al. (2005)[2]

Temporal range: Turonian-Santonian (Upper Cretaceous)[2]

Location: Bauru Basin, Adamantia Formation, Brazil[2]

Scientific classification:[2][3]

Crocodylomorpha

Crocodyliformes

Baurusuchidae

Baurusuchinae

Baurusuchus

B. salgadoensis

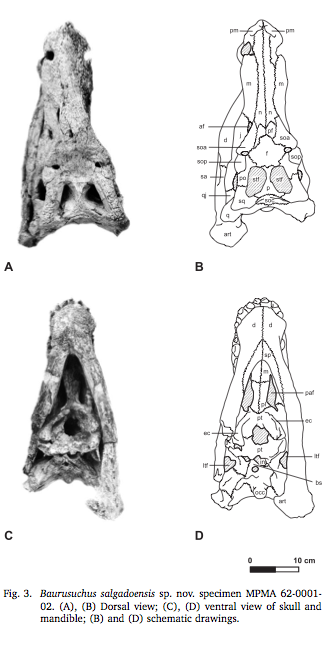

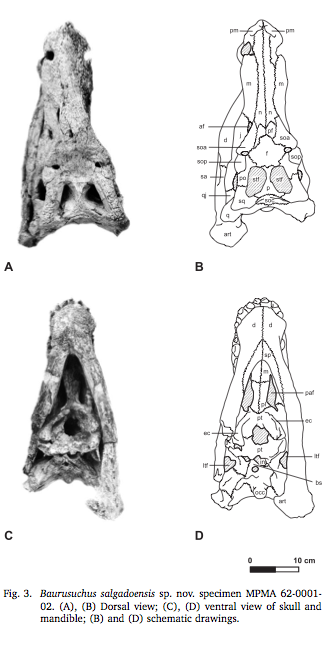

Description: Baurusuchus salgadoensis is a species of the genus Baurusuchus. It is diagnosed by a 43 cm long, elongated and laterally compressed skull.[2] The left side is completely preserved, while the right lacks the quadrate and the antorbital fenestra.[4]

©Carvalho et al. (2005)[5]

B. salgadoensis possesses large supratemporal fenestra, as well as quadrangular premaxillae and maxillae. Remarkable features include the long nasals[5] and the ziphodont dentition. The dentition is (in contrast to the fully ziphodont type species B. pachecoi) heterodont because they vary in size and some are serrated while others are not. Most are conical.[5] One of the features which can be used to distinguish B. salgadoensis from B. pachecoi is the fact that the skull is posteriorly straighter.[7] The two species were sympatric.[8]

Paleoecology

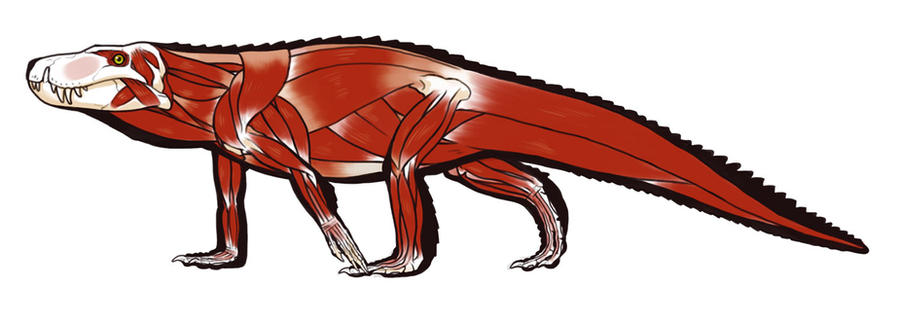

B. salgadoensis is seen as a terrestrial predator, living in hot and arid climate. The position of the external nares was unsuited for an amphibious lifestyle like in modern crocodilians and the snout and teeth are laterally compressed like in theropods. Both of this supports the terrestrial hypothesis. The hot environment hypothesis is based on the lifestyle of modern crocodilians and the stratigraphy of Baurusuchus. B. salgadoensis was found in fine massive sandstones which are interpreted as a floodplain area in hot and arid climate. Baurusuchus was likely able to dig holes for finding water in dry seasons or, like modern alligators do, for thermoregulation. The occurrence of very complete skeletons in correlated stratigraphic levels supports this. Such a strategy would have made it less water-bound than most modern crocodiles, allowing it to live in more continental climate. The strongly bent pterygoids suggest a powerful bite and that Baurusuchus could close it's jaw very quickly. The skull and teeth morphology (biology) indicates that the biting strategies of Baurusuchus were similar to a komodo dragon which include ambushing the prey, biting it and pulling back the serrated, blade-like teeth. Baurusuchus likely played an important role in its ecosystem, competing with the abelisaurids for food.[9]

Phylogeny

Baurusuchus is the type genus of the family Baurusuchidae, a family consisting of crocodilians with elongated and laterally compressed skulls.[10] Other members of that family from the Cretaceous of South America include Stratiotosuchus and Cynodontosuchus, but baurusuchids are also known from the Cretaceous of Asia (Pakistan) and the Tertiary of Europe.[11][12]

Phylogenetic relationships of Baurusuchus salgadoensis. ©Montefeltro et al. (2011)[13]

A study in 2011 erected a new subfamily called Baurusuchinae. Seven diagnostic features for the group were described which include the moderate size and the broad frontals. The paper referred only Stratiotosuchus maxhechti and Baurusuchus to the subfamily, making Stratiotosuchus Baurusuchus' closest relative so far.[3] However, a study in the year 2014 referred a new species called Aplestosuchus sordidus to the subfamily, but supported a closer relationship of Baurususchus with Stratiotosuchus than with it. The species B. albertoi is an exception. The paper does not support its affiliation to Baurusuchus and views it as a close relative of Aplestosuchus. This is the cladogram they presented:[14]

Literature:

Carvalho; Campos, Antonio; de Celso, Arruda; Nobre, Pedro Henrique (2005). Baurusuchus salgadoensis, a new Crocodylomorpha from the Bauru Basin (Cretaceous), Brazil. (PDF) In: Gondwana Research (Japan: International Association for Gondwana Research) 8 (1): pp. 11–30 doi:10.1016/S1342-937X(05)70259-8. ISSN 1342-937X.

Felipe C. Montefeltro, Hans C. E. Larsson, Max C. Lange (2011). A New Baurusuchid (Crocodyliformes, Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Late Cretaceous of Brazil and the Phylogeny of Baurusuchidae. In: PLoS ONE 6 (7): pp. 1–26. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021916.

Price, L.I. (1945). A new reptile from the Cretaceous of Brazil. In: Departamento Nacional da Produção Mineral, Notas preliminares e estudos (Rio de Janeiro) 25: pp. 1–8.

Godoy PL, Montefeltro FC, Norell MA, Langer MC (2014). An Additional Baurusuchid from the Cretaceous of Brazil with Evidence of Interspecific Predation among Crocodyliformes. In: PLoS ONE 9 (5): pp. 1–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021916.

Footnotes:

[1] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 26

[2] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 14

[3] Montefeltro et al. (2011) p. 21

[4] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 16

[5] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 17

[6] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 14

[7] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 20

[8] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 13

[9] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 24-25

[10] Price (1945; cited by Carvalho et al. (2005)

[11] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 22

[12] Montefeltro et al. (2011) p. 19

[13] Montefeltro et al. (2011) p. 19

[14] Godoy et al. (2014) p. 9

©Carvalho et al. (2005)[2]

Temporal range: Turonian-Santonian (Upper Cretaceous)[2]

Location: Bauru Basin, Adamantia Formation, Brazil[2]

Scientific classification:[2][3]

Crocodylomorpha

Crocodyliformes

Baurusuchidae

Baurusuchinae

Baurusuchus

B. salgadoensis

Description: Baurusuchus salgadoensis is a species of the genus Baurusuchus. It is diagnosed by a 43 cm long, elongated and laterally compressed skull.[2] The left side is completely preserved, while the right lacks the quadrate and the antorbital fenestra.[4]

©Carvalho et al. (2005)[5]

B. salgadoensis possesses large supratemporal fenestra, as well as quadrangular premaxillae and maxillae. Remarkable features include the long nasals[5] and the ziphodont dentition. The dentition is (in contrast to the fully ziphodont type species B. pachecoi) heterodont because they vary in size and some are serrated while others are not. Most are conical.[5] One of the features which can be used to distinguish B. salgadoensis from B. pachecoi is the fact that the skull is posteriorly straighter.[7] The two species were sympatric.[8]

Paleoecology

B. salgadoensis is seen as a terrestrial predator, living in hot and arid climate. The position of the external nares was unsuited for an amphibious lifestyle like in modern crocodilians and the snout and teeth are laterally compressed like in theropods. Both of this supports the terrestrial hypothesis. The hot environment hypothesis is based on the lifestyle of modern crocodilians and the stratigraphy of Baurusuchus. B. salgadoensis was found in fine massive sandstones which are interpreted as a floodplain area in hot and arid climate. Baurusuchus was likely able to dig holes for finding water in dry seasons or, like modern alligators do, for thermoregulation. The occurrence of very complete skeletons in correlated stratigraphic levels supports this. Such a strategy would have made it less water-bound than most modern crocodiles, allowing it to live in more continental climate. The strongly bent pterygoids suggest a powerful bite and that Baurusuchus could close it's jaw very quickly. The skull and teeth morphology (biology) indicates that the biting strategies of Baurusuchus were similar to a komodo dragon which include ambushing the prey, biting it and pulling back the serrated, blade-like teeth. Baurusuchus likely played an important role in its ecosystem, competing with the abelisaurids for food.[9]

Phylogeny

Baurusuchus is the type genus of the family Baurusuchidae, a family consisting of crocodilians with elongated and laterally compressed skulls.[10] Other members of that family from the Cretaceous of South America include Stratiotosuchus and Cynodontosuchus, but baurusuchids are also known from the Cretaceous of Asia (Pakistan) and the Tertiary of Europe.[11][12]

Phylogenetic relationships of Baurusuchus salgadoensis. ©Montefeltro et al. (2011)[13]

A study in 2011 erected a new subfamily called Baurusuchinae. Seven diagnostic features for the group were described which include the moderate size and the broad frontals. The paper referred only Stratiotosuchus maxhechti and Baurusuchus to the subfamily, making Stratiotosuchus Baurusuchus' closest relative so far.[3] However, a study in the year 2014 referred a new species called Aplestosuchus sordidus to the subfamily, but supported a closer relationship of Baurususchus with Stratiotosuchus than with it. The species B. albertoi is an exception. The paper does not support its affiliation to Baurusuchus and views it as a close relative of Aplestosuchus. This is the cladogram they presented:[14]

Literature:

Carvalho; Campos, Antonio; de Celso, Arruda; Nobre, Pedro Henrique (2005). Baurusuchus salgadoensis, a new Crocodylomorpha from the Bauru Basin (Cretaceous), Brazil. (PDF) In: Gondwana Research (Japan: International Association for Gondwana Research) 8 (1): pp. 11–30 doi:10.1016/S1342-937X(05)70259-8. ISSN 1342-937X.

Felipe C. Montefeltro, Hans C. E. Larsson, Max C. Lange (2011). A New Baurusuchid (Crocodyliformes, Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Late Cretaceous of Brazil and the Phylogeny of Baurusuchidae. In: PLoS ONE 6 (7): pp. 1–26. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021916.

Price, L.I. (1945). A new reptile from the Cretaceous of Brazil. In: Departamento Nacional da Produção Mineral, Notas preliminares e estudos (Rio de Janeiro) 25: pp. 1–8.

Godoy PL, Montefeltro FC, Norell MA, Langer MC (2014). An Additional Baurusuchid from the Cretaceous of Brazil with Evidence of Interspecific Predation among Crocodyliformes. In: PLoS ONE 9 (5): pp. 1–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021916.

Footnotes:

[1] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 26

[2] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 14

[3] Montefeltro et al. (2011) p. 21

[4] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 16

[5] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 17

[6] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 14

[7] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 20

[8] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 13

[9] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 24-25

[10] Price (1945; cited by Carvalho et al. (2005)

[11] Carvalho et al. (2005) p. 22

[12] Montefeltro et al. (2011) p. 19

[13] Montefeltro et al. (2011) p. 19

[14] Godoy et al. (2014) p. 9

_2.jpg/1186px-Baurusuchus_salgadoensis_(MPMA)_2.jpg)