Post by Infinity Blade on Jun 1, 2014 2:08:10 GMT 5

Short-faced bear – Arctodus spp.

A model of Arctodus simus. © @ Blue Rhino Studio

Temporal range: Quaternary; Pleistocene epoch (Blancan-Irvingtonian; 2.5-0.5 Ma[1] for A. pristinus) (Calabrian-Tarantian; 0.8-0.0108 Ma[2][3][4] for A. simus)

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Clade: Eutheriodonta

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicynodontia

Infraorder: Eucynodontia

Parvorder: Probainognathia

Superfamily: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

(unranked): Pegasoferae

(unranked): Zooamata

Clade: Holotheria

Superlegion: Trechnotheria

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Eutheria

Infraclass: Placentalia

Subcohort: Exafroplacentalia

Magnorder: Boreoeutheria

Superorder: Laurasiatheria

(unranked): Ferae

(unranked): Carnivoramorpha

Order: Carnivora

Suborder: Caniformia

Infraorder: Arctoidea

Family: Ursidae

Subfamily: Tremarctinae

Tribe: Tremarctini

Genus: †Arctodus

Species: †A. simus

†A. pristinus

Arctodus ("bear tooth") was a genus of tremarctine bear that lived in North America in from 2.5 million to ~10,800 years ago.[1][2][3][4] There are two species in the genus: A. pristinus and A. simus.

Description & functional morphology:

In a 2010 study, a third of the A. simus sampled approached 1,000 kg, suggesting such specimens were more common than previously suspected. Similarly, two of the specimens were estimated to weigh 300-400 kg, consistent with the marked sexual dimorphism seen in extant ursids.[5] A. pristinus also displayed marked sexual dimorphism; males of this smaller species overlapped in size with females of A. simus and the extinct Tremarctos floridanus.[1]

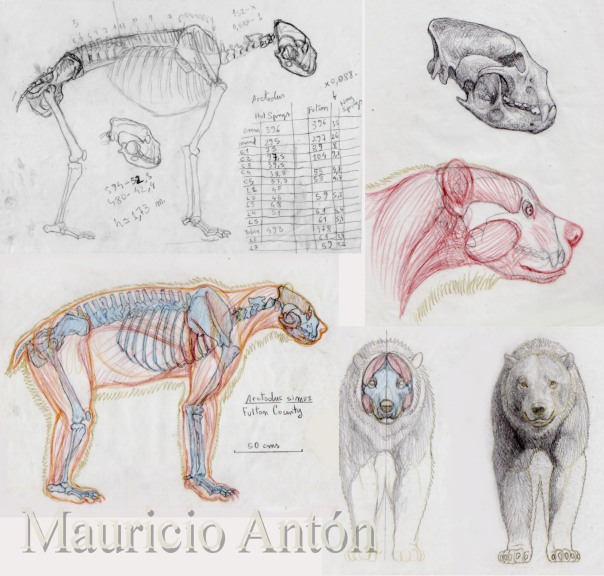

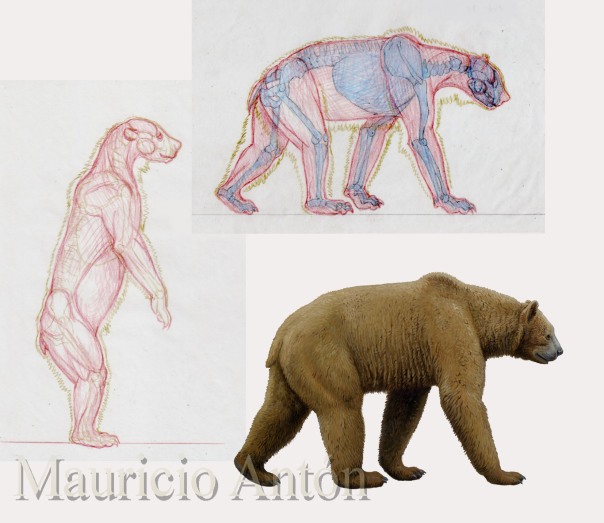

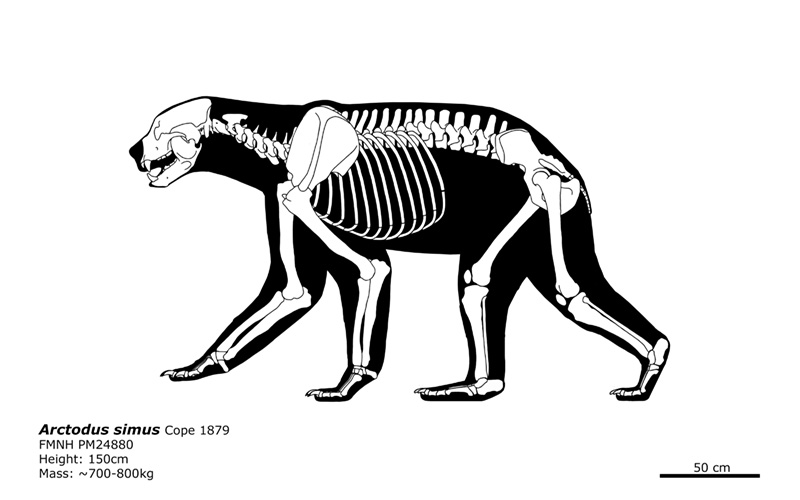

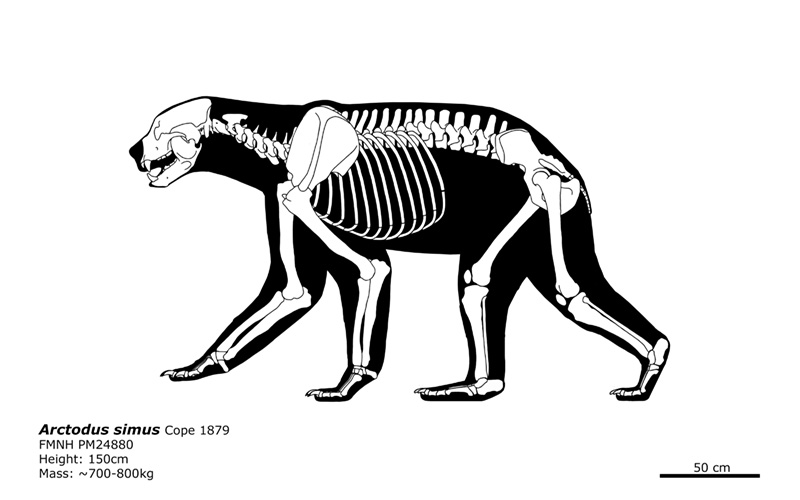

Skeletal of A. simus. © @ bLAZZE92

Contrary to its popular name, the short faced bear did not actually possess a particularly foreshortened face for a bear, although it did possess a proportionately deeper snout. Its long-legged appearance is sort of an optical illusion created by its rather short back.[5]

Sorkin (2006) analyzed the skeletal remains of A. simus (in addition to those of Agriotherium africanum, which was surprisingly convergent to Arctodus) to test the idea that Arctodus was a hypercarnivore. The anatomical features that served as evidence for hypercarnivory ("sectorial carnassials, position of the mandibular condyle, and development of the angular process") were all found to be present in Tremarctos, a borderline herbivorous bear. Likewise, the buccal cusps present on the upper molars are present in the extant Kodiak bear (Ursus arctos middendorfi). Other things Sorkin noted were that:

- the upper canines were proportionately short (rendering it unadapted to killing akin to a big cat).

- the orbits were small and more laterally placed than those of felids (vision is vital to predation).

- relative to the brown bear, the forelimbs did not seem as adept at grappling with prey ("reduced leverage of deltoid and pectoralis muscles [used to subdue prey], reduced development of the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles [used to grasp prey], reduced pronation of the forearm and the flexation of the wrist and digits [used to grasp prey]”).

- the olecranon process was short and bent (meaning it couldn't crouch very well, reducing ambushing ability).

- the lumbar vertebrae were stiff like those of U. arctos and had limited flexion in the sagittal plane (decreasing its top speed and acceleration).[6]

And at least in Arctodus:

- relative to the proximal limb segments, the distal limb segments of Arctodus were just as short, if not shorter, than those of U. arctos, and certainly far shorter than those of extant cursorial, and even ambush, predators.

- the hind feet were plantigrade, unlike in extant predators that utilize speed for predation.[6]

A 2012 thesis dissertation found that the forelimbs of A. simus feature a number of cursorial adaptations, and that the species represents an early step in the evolution of a cursorial bear. These features include (1) reduced attachment areas for muscles that controlled abduction-adduction and pronation-supination, (2) reorientation of the joints nearer to the parasagittal plane, and (3) relatively gracility of the forelimb bones compared to other bears (these features are consistent with an inferior ability to subdue prey with the forelimbs as asserted in [6]).[7] The laterally compressed ribcage of Arctodus is also consistent with greater cursorial ability, reducing the lateral excursion of the limbs taken during each step.[8] It is also thought that the relatively gracile limbs of Arctodus, combined with its great size, would have rendered it incapable of withstanding the dynamic forces of rapid acceleration or maneuverability that modern mammalian predators exhibit (but capable of moderately fast, straight-line coursing, using energetically efficient paces to traverse through a wide home range[8]), although this needs to be empirically tested with biomechanical analysis.[7]

A 2013 study on the microwear of Arctodus' teeth suggested that it was not a durophagous animal, contrary to popular belief. This study also noted that Arctodus possessed cranial features that herbivorous bears tend to possess. These include "cheek teeth with large surface areas, a deep mandible, and large mandibular muscle attachments". It was also noted that "because herbivorous carnivorans lack an efficient digestive tract for breaking down plant matter via microbial action, they must break down plant matter via extensive chewing or grinding, and thus possess features to create a high mechanical advantage of the jaw".[9] This may explain the broad, deep, and short jaws of Arctodus, which would have evidently had excellent mechanical advantage.

Diet:

Multiple isotope analyses have revealed that A. simus specimens in Beringia and British Columbia incorporated terrestrial meat in their diet, especially caribou. However, some specimens with higher levels of δ15N indicate that A. simus in the mammoth steppe were also likely preying on muskoxen or even killing other predators for consumption. Kleptoparisitism and scavenging (of both marine and terrestrial carcasses across a wide home range) are also likely. These isotope values also do not mean that the short-faced bear was not eating plants; up to 50% of its diet may have been plant food. Interestingly, A. simus from the mammoth steppe were not consuming a significant amount of mammoth or horse meat, despite these two species composing ~50% of the herbivore biomass in this ecosystem.[10][11]

Bite marks found on the bones of many sloths and young proboscideans found in the Leisey Shell Pit match the canines of A. pristinus. It is unknown if these bite marks were the result of successful predation or scavenging.[1]

Extinction:

The short faced bear went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene epoch about ~10,800 years ago. It is clear that A. simus overlapped with the Clovis culture both temporally and geographically. Because A. simus is known to have consumed a substantial portion of meat, this suggests competition between both humans and Arctodus.[4]

Skeleton of A. simus with Equus occidentalis.

References:

[1] www.flmnh.ufl.edu/florida-vertebrate-fossils/species/arctodus-pristinus

[2] Churcher, C. S., Morgan, A. V., & Carter, L. D. (1993). Arctodus simus from the Alaskan Arctic slope. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 30(5), 1007-1013.

[3] Cassiliano, M. L. (1999). Biostratigraphy of Blancan and Irvingtonian mammals in the Fish Creek-Vallecito section, southern California, and a review of the Blancan–Irvingtonian boundary. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 19(1), 169-186.

[4] Schubert, B. W. (2010). Late Quaternary chronology and extinction of North American giant short-faced bears (Arctodus simus). Quaternary International, 217(1-2), 188-194.

[5] Borja Figueirido, Juan A. Pérez-Claros, Vanessa Torregrosa, Alberto Martín-Serra & Paul Palmqvist (2010) Demythologizing Arctodus simus, the ‘short-faced’ long-legged and predaceous bear that never was, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 30:1, 262-275, DOI: 10.1080/02724630903416027

[6] B. Sorkin (2006) Ecomorphology of the giant short-faced bears Agriotherium and Arctodus, Historical Biology, 18:1, 1-20, DOI: 10.1080/08912960500476366

[7] Lynch, Eric Randally, “Cursorial Adaptations in the Forelimb of the Giant Short-Faced Bear, Arctodus simus, Revealed by Traditional and 3D Landmark Morphometrics“ (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1477. dc.etsu.edu/etd/1477

[8] Matheus, P. E. (2003). Locomotor adaptations and ecomorphology of short-faced bears (Arctodus simus) in eastern Beringia. Yukon Palaeontology Program, Department of Tourism and Culture.

[9] Donohue, S. L., DeSantis, L. R., Schubert, B. W., & Ungar, P. S. (2013). Was the giant short-faced bear a hyper-scavenger? A new approach to the dietary study of ursids using dental microwear textures. PloS one, 8(10), e77531. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077531

[10] Mychajliw, A.M., Rick, T.C., Dagtas, N.D. et al. Biogeographic problem-solving reveals the Late Pleistocene translocation of a short-faced bear to the California Channel Islands. Sci Rep 10, 15172 (2020). doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71572-z

[11] Bocherens, H. (2015). Isotopic tracking of large carnivore palaeoecology in the mammoth steppe. Quaternary Science Reviews, 117, 42-71.

A model of Arctodus simus. © @ Blue Rhino Studio

Temporal range: Quaternary; Pleistocene epoch (Blancan-Irvingtonian; 2.5-0.5 Ma[1] for A. pristinus) (Calabrian-Tarantian; 0.8-0.0108 Ma[2][3][4] for A. simus)

Scientific classification:

Life

Domain: Eukaryota

(unranked): Unikonta

(unranked): Opisthokonta

(unranked): Holozoa

(unranked): Filozoa

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Eumetazoa

(unranked): Bilateria

Clade: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Clade: Olfactores

Clade: Craniata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Clade: Eugnathostomata

Clade: Teleostomi

Superclass: Tetrapoda

Clade: Reptiliomorpha

Clade: Amniota

Clade: Synapsida

Clade: Eupelycosauria

Clade: Sphenacodontia

Clade: Sphenacodontoidea

Order: Therapsida

Clade: Eutheriodonta

Suborder: Cynodontia

Clade: Epicynodontia

Infraorder: Eucynodontia

Parvorder: Probainognathia

Superfamily: Chiniquodontoidea

Clade: Prozostrodontia

Clade: Mammaliaformes

Class: Mammalia

(unranked): Pegasoferae

(unranked): Zooamata

Clade: Holotheria

Superlegion: Trechnotheria

Legion: Cladotheria

Sublegion: Zatheria

Infralegion: Tribosphenida

Subclass: Theria

Clade: Eutheria

Infraclass: Placentalia

Subcohort: Exafroplacentalia

Magnorder: Boreoeutheria

Superorder: Laurasiatheria

(unranked): Ferae

(unranked): Carnivoramorpha

Order: Carnivora

Suborder: Caniformia

Infraorder: Arctoidea

Family: Ursidae

Subfamily: Tremarctinae

Tribe: Tremarctini

Genus: †Arctodus

Species: †A. simus

†A. pristinus

Arctodus ("bear tooth") was a genus of tremarctine bear that lived in North America in from 2.5 million to ~10,800 years ago.[1][2][3][4] There are two species in the genus: A. pristinus and A. simus.

Description & functional morphology:

In a 2010 study, a third of the A. simus sampled approached 1,000 kg, suggesting such specimens were more common than previously suspected. Similarly, two of the specimens were estimated to weigh 300-400 kg, consistent with the marked sexual dimorphism seen in extant ursids.[5] A. pristinus also displayed marked sexual dimorphism; males of this smaller species overlapped in size with females of A. simus and the extinct Tremarctos floridanus.[1]

Skeletal of A. simus. © @ bLAZZE92

Contrary to its popular name, the short faced bear did not actually possess a particularly foreshortened face for a bear, although it did possess a proportionately deeper snout. Its long-legged appearance is sort of an optical illusion created by its rather short back.[5]

Sorkin (2006) analyzed the skeletal remains of A. simus (in addition to those of Agriotherium africanum, which was surprisingly convergent to Arctodus) to test the idea that Arctodus was a hypercarnivore. The anatomical features that served as evidence for hypercarnivory ("sectorial carnassials, position of the mandibular condyle, and development of the angular process") were all found to be present in Tremarctos, a borderline herbivorous bear. Likewise, the buccal cusps present on the upper molars are present in the extant Kodiak bear (Ursus arctos middendorfi). Other things Sorkin noted were that:

- the upper canines were proportionately short (rendering it unadapted to killing akin to a big cat).

- the orbits were small and more laterally placed than those of felids (vision is vital to predation).

- relative to the brown bear, the forelimbs did not seem as adept at grappling with prey ("reduced leverage of deltoid and pectoralis muscles [used to subdue prey], reduced development of the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles [used to grasp prey], reduced pronation of the forearm and the flexation of the wrist and digits [used to grasp prey]”).

- the olecranon process was short and bent (meaning it couldn't crouch very well, reducing ambushing ability).

- the lumbar vertebrae were stiff like those of U. arctos and had limited flexion in the sagittal plane (decreasing its top speed and acceleration).[6]

And at least in Arctodus:

- relative to the proximal limb segments, the distal limb segments of Arctodus were just as short, if not shorter, than those of U. arctos, and certainly far shorter than those of extant cursorial, and even ambush, predators.

- the hind feet were plantigrade, unlike in extant predators that utilize speed for predation.[6]

A 2012 thesis dissertation found that the forelimbs of A. simus feature a number of cursorial adaptations, and that the species represents an early step in the evolution of a cursorial bear. These features include (1) reduced attachment areas for muscles that controlled abduction-adduction and pronation-supination, (2) reorientation of the joints nearer to the parasagittal plane, and (3) relatively gracility of the forelimb bones compared to other bears (these features are consistent with an inferior ability to subdue prey with the forelimbs as asserted in [6]).[7] The laterally compressed ribcage of Arctodus is also consistent with greater cursorial ability, reducing the lateral excursion of the limbs taken during each step.[8] It is also thought that the relatively gracile limbs of Arctodus, combined with its great size, would have rendered it incapable of withstanding the dynamic forces of rapid acceleration or maneuverability that modern mammalian predators exhibit (but capable of moderately fast, straight-line coursing, using energetically efficient paces to traverse through a wide home range[8]), although this needs to be empirically tested with biomechanical analysis.[7]

A 2013 study on the microwear of Arctodus' teeth suggested that it was not a durophagous animal, contrary to popular belief. This study also noted that Arctodus possessed cranial features that herbivorous bears tend to possess. These include "cheek teeth with large surface areas, a deep mandible, and large mandibular muscle attachments". It was also noted that "because herbivorous carnivorans lack an efficient digestive tract for breaking down plant matter via microbial action, they must break down plant matter via extensive chewing or grinding, and thus possess features to create a high mechanical advantage of the jaw".[9] This may explain the broad, deep, and short jaws of Arctodus, which would have evidently had excellent mechanical advantage.

Diet:

Multiple isotope analyses have revealed that A. simus specimens in Beringia and British Columbia incorporated terrestrial meat in their diet, especially caribou. However, some specimens with higher levels of δ15N indicate that A. simus in the mammoth steppe were also likely preying on muskoxen or even killing other predators for consumption. Kleptoparisitism and scavenging (of both marine and terrestrial carcasses across a wide home range) are also likely. These isotope values also do not mean that the short-faced bear was not eating plants; up to 50% of its diet may have been plant food. Interestingly, A. simus from the mammoth steppe were not consuming a significant amount of mammoth or horse meat, despite these two species composing ~50% of the herbivore biomass in this ecosystem.[10][11]

Bite marks found on the bones of many sloths and young proboscideans found in the Leisey Shell Pit match the canines of A. pristinus. It is unknown if these bite marks were the result of successful predation or scavenging.[1]

Extinction:

The short faced bear went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene epoch about ~10,800 years ago. It is clear that A. simus overlapped with the Clovis culture both temporally and geographically. Because A. simus is known to have consumed a substantial portion of meat, this suggests competition between both humans and Arctodus.[4]

Skeleton of A. simus with Equus occidentalis.

References:

[1] www.flmnh.ufl.edu/florida-vertebrate-fossils/species/arctodus-pristinus

[2] Churcher, C. S., Morgan, A. V., & Carter, L. D. (1993). Arctodus simus from the Alaskan Arctic slope. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 30(5), 1007-1013.

[3] Cassiliano, M. L. (1999). Biostratigraphy of Blancan and Irvingtonian mammals in the Fish Creek-Vallecito section, southern California, and a review of the Blancan–Irvingtonian boundary. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 19(1), 169-186.

[4] Schubert, B. W. (2010). Late Quaternary chronology and extinction of North American giant short-faced bears (Arctodus simus). Quaternary International, 217(1-2), 188-194.

[5] Borja Figueirido, Juan A. Pérez-Claros, Vanessa Torregrosa, Alberto Martín-Serra & Paul Palmqvist (2010) Demythologizing Arctodus simus, the ‘short-faced’ long-legged and predaceous bear that never was, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 30:1, 262-275, DOI: 10.1080/02724630903416027

[6] B. Sorkin (2006) Ecomorphology of the giant short-faced bears Agriotherium and Arctodus, Historical Biology, 18:1, 1-20, DOI: 10.1080/08912960500476366

[7] Lynch, Eric Randally, “Cursorial Adaptations in the Forelimb of the Giant Short-Faced Bear, Arctodus simus, Revealed by Traditional and 3D Landmark Morphometrics“ (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1477. dc.etsu.edu/etd/1477

[8] Matheus, P. E. (2003). Locomotor adaptations and ecomorphology of short-faced bears (Arctodus simus) in eastern Beringia. Yukon Palaeontology Program, Department of Tourism and Culture.

[9] Donohue, S. L., DeSantis, L. R., Schubert, B. W., & Ungar, P. S. (2013). Was the giant short-faced bear a hyper-scavenger? A new approach to the dietary study of ursids using dental microwear textures. PloS one, 8(10), e77531. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077531

[10] Mychajliw, A.M., Rick, T.C., Dagtas, N.D. et al. Biogeographic problem-solving reveals the Late Pleistocene translocation of a short-faced bear to the California Channel Islands. Sci Rep 10, 15172 (2020). doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71572-z

[11] Bocherens, H. (2015). Isotopic tracking of large carnivore palaeoecology in the mammoth steppe. Quaternary Science Reviews, 117, 42-71.