smedz

Junior Member

Posts: 195

|

Post by smedz on Feb 19, 2020 5:51:33 GMT 5

Yeah, a lot of the animal in the last 2 places are implausible. Birds as they evolved lost their "killing claws" on their arms as they have no use for them, so why would the carakiller even evolve something birds were trying to get rid of?

One thing I would like to mention is the lack of biodiversity in these habitats. In all these there are only 3 animals per ecosystem, why?

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 19, 2020 5:57:48 GMT 5

Yeah, that becomes apparent when you look at my posts here. I'm sure there are far more than just 3 animals in each ecosystem. It's just that with the format of the original show, where they take their time to explain how the animal works, how it evolved, and why it's plausible (showing footage of modern animals for precedents), it's kind of difficult to have all this kind of information for a wide variety of animals in each episode, which is like what? 25 minutes long?

|

|

|

|

Post by dinosauria101 on Feb 19, 2020 21:57:36 GMT 5

So, correct me if I'm wrong, but this show is all about speculating what might evolve from which animals and why?

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 19, 2020 22:02:47 GMT 5

I've also added a new rank 'very implausible' (between 'implausible' and 'extremely implausible'). Admit it, you only did this for the mega-spiders.Nevermind, if the spink is already borderline "very implausible", that rank's gonna be handed out like candy in the next posts. The spink is indeed an odd creature. It's so unbirdlike that I forgot it was a bird at all and called it "bunny mole" in my last post. I think The Future Is Wild suffers from what is perhaps the central problem of all docufiction: The need to balance entertainment and scientific realism. I mean, what was the world like five million years ago? South America was basically a second Australia in terms of weirdness and many critters had different distribution ranges than today, but otherwise, the world was very recognizable. It's fun to swap the niches of present day taxa (e.g. "What if birds were marine mammals?") and provides the show with novelty. But unfortunately, there is usually a reason why certain creatures are without precedent. Imagining the world a 100 to 200 million years ago has the opposite problem: The world is bound to be weird, but unfortunately, it's gonna be far more weird or a very different weird than anyone can envision. But I'm sure you'll have far more about that to say. |

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 19, 2020 22:04:56 GMT 5

So, correct me if I'm wrong, but this show is all about speculating what might evolve from which animals and why? Yeah. It feels like many of our favorite dinosaur documentaries, but with future creatures rather than dinosaurs. I strongly recommend it if you are even remotely interested into speculative evolution. For all its flaws, it's among the best of its kind. |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 19, 2020 23:39:57 GMT 5

Good point. And it's worth noting that the only reason South America was even like that was because of its isolation from continents with more familiar fauna.

Edit: actually, I think that was your point, wasn’t it? Now I feel dumb for reiterating it.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 20, 2020 3:03:01 GMT 5

Good point. And it's worth noting that the only reason South America was even like that was because of its isolation from continents with more familiar fauna. Edit: actually, I think that was your point, wasn’t it? Now I feel dumb for reiterating it. Your point was a nice expansion of my point.  On the other hand, it should be taken into account that there is a difference between five million years in the future and five million years in the past: The former will include an anthropogenic mass extinction event of unknown magnitude. However, since TFIW did not bother to go in more detail on how exactly said mass extinction event played out, it might be a moot point. |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 20, 2020 5:27:42 GMT 5

I've reviewed the toraton, but I'm having some trouble with the swampus because I'm nowhere near as knowledgable on invertebrates as I am with vertebrates (and even then it's only tetrapods, if not just amniotes). So I've asked some people elsewhere for assistance. Hopefully they'll help me out.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 20, 2020 16:43:55 GMT 5

I'm by no means an invertebrate expert, but the Swampus probably suffers from the "why now?" problem. Cephalopods have been around for a really, really long time, yet despite surviving countless mass extinctions, none of them felt like going on land.

I have no idea why, to be honest, or if there is a certain set of conditions that would favor them going on land. What I do know is that, while returns into the water have been common among several groups, significant conquests of land only happened around the Devonian and never again.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Feb 21, 2020 3:51:49 GMT 5

Very nice work! I think this really highlights the central plausibility problem of TFIW:

It is trying to swap out everything we know today with something entirely unrelated but filling a similar niche as quickly as possible, including having taxa swap places without any logical reason for them to do so. Doesn’t matter that there are mammals far more likely to fill that role, why not have giant cetacean-like birds filling the role of marine tetrapods only 5 Million years from now? Doesn’t matter that flying birds and burrowing mammals seem to be doing well enough, let’s just have them swap roles without any reasoning as to why it’s more likely that a bird would evolve into a eusocial burrower than, one of the many mammals that is already burrowing filling that role. It would have made a bit more sense if they had actually shown the taxa being replaced in their niches going extinct, but no, rodents are doing just fine, they just seemingly aren’t burrowing any more. Birds are doing just fine too, they merely chose to take a page from Greta’s book and stop flying, apparently.

As entertaining as that is, and as cool as the designs are, that makes no freakin’ sense. 5 Million years in the future should be less alien to us than 5 million years ago, because 5 Million years ago there were still many animals (especially endemic Australasian, South American and Island species) shaped by long-lasting isolation that have gone extinct since, but which had evolved in isolation from the fauna we are familiar with for much longer than the maximum of 5 Ma that could happen between now and…well, 5 Ma in the future.

That segment of the show didn’t go totally over board (and it’s not that I have any problem with mustelids or rodents or birds doing well and diversifying in the future), but it did already hint at what was to come in terms of stuff getting way too weird way too fast. I mean seriously, all vertebrates except fish being extinct by 200 Ma (and again, Actinopterygians hell yes, but everywhere except in the niches they are known to occupy?)? Not so terribly likely.

But still, really fun to watch, looking forward to the next set of reviews!

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 21, 2020 4:22:43 GMT 5

It might even have been possible for TFIW to have its cake and eat it, too. They could have maintained both the fantastical creatures and the willing suspension of disbelief among their audience had they gone into more detail on what happened between their time jumps. Like, why exactly all vertebrates go extinct? How did this mass extinction that must have even put the Permian-Triassic boundary to shame even look like?

And what the hell happened to humans? No, I'm not willing to buy that they left the Earth for the stars (as at least one version alludes to), even sci-fi plots which are just about that typically don't make sense. There would have been a lot of material to work with for a human extinction episode and it might have explained some of their later creatures. Maybe humans accidentally spilled a waterborne plague that immediately killed all marine mammals upon contact (with more time and thought, you could come up with a less silly explanation for the whale-birds).

I have two main guesses why they didn't cover the extinctions. One is that their time and budget wasn't enough. The other is that they thought it would alienate their target audience. Surely, people who are here for the fantastical creatures won't want a pilot episode about how humanity exterminated itself in a robot war.

The way it is, the show sounds too much as if it was trying to sell the most likely possibility and not just one (very cool one) among many.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 21, 2020 5:55:46 GMT 5

I definitely think the former was a significant constraint (especially time). The latter actually sounds possible too. In the original British version, humans have flat-out gone extinct (for an unknown reason; the pilot apparently states it's up to the viewers to decide). The subsequent American version changes this to the whole "left Earth for some other celestial body" explanation for the absence of humanity.

I do wish the pilot went more into these explanations and less summarizing what evolves in the future. I mean, that's literally what the episodes proper are for!

Anyway, I only have one more animal from the Bengal Swamp to review.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 21, 2020 6:17:13 GMT 5

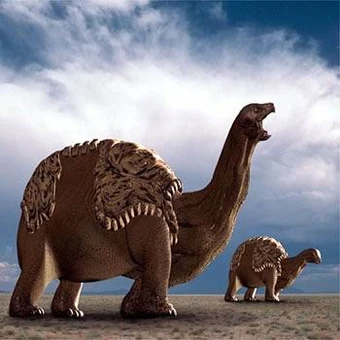

Waterland (100,000,000 CE)Toraton:  Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->This is a giant herbivorous tortoise. It has erect limbs to better support its weight (like elephants, sauropods, etc., etc.). It has reduced its shell (given how it's so big that it doesn't really need it), but the shell that remains is used to anchor muscles to help bear weight (stated in The Future is Wild The Living Book). The toraton still has the typical ectothermic metabolism of modern non-avian reptiles, but it still needs to eat a lot. It uses its scissor-like keratinous beak to shear off twigs and leaves. It doesn't chew, but it uses a complex digestive system to break down pretty much any plant matter. At least according to the living book, toraton eggs have shells so tough that the hatchling needs the adults to tear the eggshells with their beaks to break them out. They're so big that they need to mate with their rear ends facing each other, so no mounting each other like in modern tortoises. With this information in mind the reader is probably wondering "Just how big is the toraton?". Well... " The adults are enormous. The biggest animals that have ever walked on the face of the planet. A hundred and twenty tonnes [130+ according to The Living Book]. That's bigger than even the biggest dinosaur.". ~Mike Linley (herpetologist) ...  How dare these people have a lowly tortoise become bigger than my lovely dinosaurs!!?? First the blue whale and now a tortoise!!?? NO! NOT HAPPENING!! ABSOLUTELY IMPLAUSIBLE!!! REVIEW OVER!!!! How dare these people have a lowly tortoise become bigger than my lovely dinosaurs!!?? First the blue whale and now a tortoise!!?? NO! NOT HAPPENING!! ABSOLUTELY IMPLAUSIBLE!!! REVIEW OVER!!!!…I’m just kidding, of course. Except for the part regarding plausibility. So, here we have a terrestrial tortoise comparable in size to some of the largest fragmentary sauropods (for what it's worth, Greg Paul in his recent sauropod paper estimates Maraapunisaurus fragillimus to have weighed ~80-120 tonnes when restored as a robust basal diplodocoid; i.e. a rebbachisaurid), and larger than all sauropods known from reasonable remains. However, we now know that a sauropod isn't simply some scaled-up tortoise. Unlike the toraton and its ancestors, sauropods were endotherms. In fact, they had to be endotherms from birth, otherwise they wouldn't be able to stay warm enough to maintain the kind of metabolism needed for other bodily functions like digestion. As endotherms, they were able to grow rapidly. If sauropods had an ectothermic metabolism from hatching, it probably would have taken them an impossible 70-200 years just to grow to mature size [1]. In fact, the source I just cited even specifically calls out the toraton ( to my delight), stating that without fast growth driven by a rapid metabolism, there would be no way toratons could have survived the decades, if not centuries, needed to reach hundreds of tonnes. And without skeletal pneumatization (perhaps among other adaptations for gigantism), they would not be able to support themselves on land. Yes, the toraton is apparently stated (by The Living Book, at least) to have carapace remnants that serve as additional muscle anchors to bear its weight (because the ribs and vertebrae apparently can't bear this weight by themselves), but no detail is given as to how the muscles are exactly arranged and whether or not such a myological arrangement could indeed successfully bear the toraton's weight (not that I blame them, because that's even more work). Having additional muscle attachments also sounds quite metabolically costly, especially on an animal that weighs 120+ tonnes, in contrast to pneumatization. Final verdict: SUCK IT TORATON! extremely implausible. Swampus:  Taken from the Speculative Evolution wiki->A predatory octopus that spends its time in both water and on land. The warm humid climate of the hothouse Earth 100 million years in the future apparently gives these octopi more time to spend on land (which supposedly negates the need for waterproof skin). To be able to breathe on land, it has evolved a specialized lining within the body cavity with a very rich blood supply; in effect, it has evolved a lung. This adaptation allows it to breathe on land to some extent (it still needs to return to the water frequently for oxygen). Four of its eight arms have basically become sleigh runners (in the form of fleshy pads) that let it haul itself across land with the other four arms; according to The Living Book, these carry the swampus via muscular waves and keratinous pads (derived from the suckers) that grip the ground. The reason why swampus have ventured onto land is to protect their young (from aquatic predators) and house them in water-filled, vase-like plants acting as nurseries. Adults can then gather around the nursery plant and guard it. When they or their young are threatened, swampus will grasp their assailants with their tentacles and land a venomous bite (it’s a neurotoxin btw), potent enough to kill a baby toraton (which is the size of an elephant). In the water of the vase-like nursery plants, bacteria produce a toxin that is not harmful to the baby swampus, and in fact becomes the basis for their venomous bite as adults. Females are even shown to intrude on the nurseries of other swampus, and this results in displays of swampus waving their arms up in the air and flashing bright colors from their skin. I have to admit, it was difficult determining how plausible this was, considering how little I know on invertebrates (it’s probably going to be like this from now on). I can excuse the venom and the venturing onto land (although, whether to the extent that the swampus does, not sure), considering these are both true for modern octopi. I find myself questioning as to whether or not the runner-like tentacles would (or could) evolve. It seems like it would take more energy for a swampus to have to haul itself on land with only half as many arms to use. And on an animal confronted with the challenge to have enough oxygen to breathe on land (considering this is an octopus), this would seem especially problematic. Yes, the other four are apparently snail foot-like runners now, but I’m kind of under the impression that using limbs to haul yourself on land is going to get you places more efficiently than snail feet. As for the specialized lung-like lining in its body cavity, that again seems unlikely for an octopus to evolve (at least to my cephalopod-ignorant mind). I’ve seen a criticism (by someone surely more knowledgable on cephalopods than I) asking why the swampus couldn’t simply breathe through its skin like a frog or a mudskipper; after all, this future atmosphere has more oxygen in it. Final verdict (at least as far as I can tell): implausible, at least. Lurkfish:  Taken from the Speculative Evolution wiki->The apex predator of the Bengal swamp of 100 million CE. Apparently one of the few creatures that can kill a swampus. The lurkfish can't see very far in the murky waters it inhabits, but can sense prey up to 5 meters way using sensory barbels. It surrounds itself with a weak electric field and feels its prey moving through it. When large prey (like a swampus) gets close, the lurkfish stuns it with a massive electric shock generated within a large number of muscle blocks in its >4 meter body (like a giant electric eel) and blasted out through its barbels. In just seconds, it generates 1,000 volts. Using electricity, the lurkfish can kill a swampus without having to worry about its venomous bite. I had to go onto TierZoo's review of the series on Reddit to quickly find anything regarding how plausible this one is. Basically, given how electric eels and other knifefish using electricity are a thing today, a fish using electricity as an ambush weapon in the future may not seem so bad. Final verdict: plausible (wow I wasn't expecting any plausible animal here; I might have to do more research and update this if I can). [1] Sauropod Dinosaurs: Life in the Age of Giants (unfortunately the pages talking about the toraton are no longer previewable).

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 21, 2020 19:48:10 GMT 5

I kinda expected the lurkfish to be the most plausible. It is the least outlandish (and unfortunately also the most forgettable) of the three.

The toraton is unfortunately one of the most extreme examples of TFIW prioritizing coolness over plausibility. It's not enough for turtles to grow big, no, they have to be larger than the largest dinosaurs (which are probably the only large animals besides elephants that our target audience knows about). The problem is, sauropods are utterly exceptional from a geological perspective. In order to grow as big (or bigger!) than them, you'd basically need to copy everything that allowed them to become so big (their metabolism, their extremely long tails and necks, their pneumatic bones) which isn't something every taxon can do.

It wasn't even necessary to make the toraton so big. The megasquid is only as big as an elephant and it is by far one of TFIW's most iconic creatures. The toraton meanwhile comes off as too much of a sauropod knockoff to be all that memorable.

While it's plausibility is debatable, including the swampus in this episode was really clever. It's one of the few times where TFIW has done something it should do more often: Including transitional forms.

I'd wager to say that the megasquid and the squibbon would have been laughed off and forgotten had they come out of nowhere rather than being foreshadowed by the swampus.

|

|

|

|

Post by dinosauria101 on Feb 21, 2020 22:37:47 GMT 5

The swampus isn't THAT unrealistic, is it? Aren't there tide pool octopuses with basically the same life style?

|

|