The Future is Wild: Plausibility of the Bestiary

Feb 26, 2020 9:37:17 GMT 5

creature386 and DonaldCengXiongAzuma like this

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 26, 2020 9:37:17 GMT 5

The Great Plateau (100,000,000 CE)

Great blue windrunner:

Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->

A giant (3 meter wingspan) crane descendant that is metallic blue, and an annual migrant to the great plateau for breeding. It is this color because at high altitudes, there is little protection from UV light. The metallic blue plumage helps reflect UV light and protect the bird. The nictitating membranes are polarized to protect the eyes from UV light, effectively making them organic sunglasses. Windrunners can tell other individuals apart by looking at distinctive UV light patterns on their plumage (being able to see in ultraviolet). The other notable thing about this bird is that it has four wings. The trade-offs associated with wing morphology and function have become too much in this ecosystem where the plateau stretches for thousands of kilometers and reaches higher up than the Himalayas today (>12,000 meters above sea level), conditions no bird today has to live under. The great blue windrunner needs to be both fast (and presumably energetically efficient when flying fast) and maneuverable at the same time. So the bird uses just its two forewings (long and narrow, like those of a condor) when soaring great distances over the vast plateau at high speed. But when it needs maneuverability (like when it needs to see the ground better at lower speeds), it spreads its feathered hindlimbs out laterally. What this does is it effectively gives the windrunner more wing area when needed, which can be retracted back when greater soaring speed is needed again. Also, the bird has small feathers on the sides of its neck (right behind the head) called canards, which stabilize the head during flight. In the great plateau, it preys upon the silver spiders.

There’s nothing about this bird that jumps out at me as implausible. At first I was wondering why this bird has suddenly cheat coded the trade-offs of wing morphology and function (and having the best of both worlds) but this is explained as a result of the fact that no bird alive today has to live in conditions this harsh, which I can excuse. The four wings I can pass considering we have feathered theropods from the fossil record with just that (look no further than Microraptor). Final verdict: plausible.

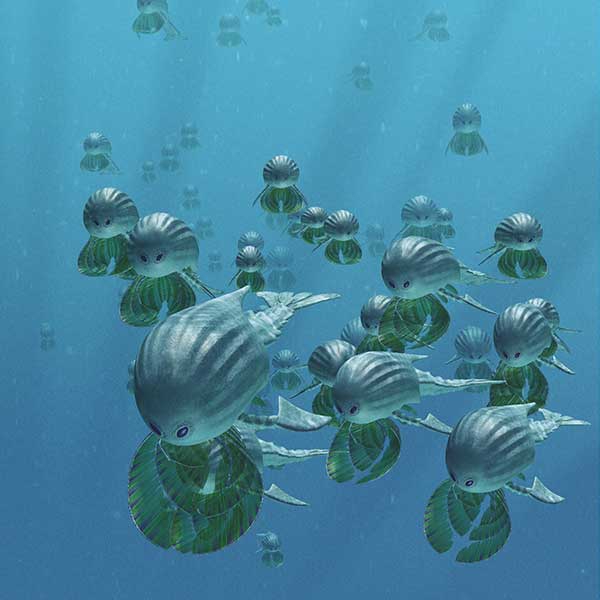

Silver spider:

Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->

Very self-explanatory name. The silver is this spider’s way of reflecting harmful UV light. Oh, and they're also larger than today's spiders (by how much I don't know). They construct large webs spanning across the canyons of the great plateau, numbering in the hundreds (pretty sure these are different families/groups). To create webs this large, silver spiders not only work together, but are divided amongst different caste depending on their age and size. There are those that cast the first lines (they are smaller), those that cast the actual webs (larger), and the massive queen that stays inside their rock crevice home and lays eggs. These large webs trap many seeds from the grass trees that float via the wind. They use this to feed the poggles that live in the rock crevices with them. After a certain point, poggles are killed and fed to the queen.

I'm using the opinion of someone else I've read online to guide my final verdict. While the colonial aspect of the silver spiders' behavior may be believable, their farming of poggles is...not, really. This person pointed out that, while there are ants that raise aphids, aphids are very simple creatures that mostly reproduce by basically cloning themselves (asexual reproduction, I assume) and don't move very much if it's not necessary. A poggle is a mammal, and almost certainly going to be more mobile and curious, thus a lot harder to farm by some spiders. Final verdict: very implausible (there creature, I used it lol).

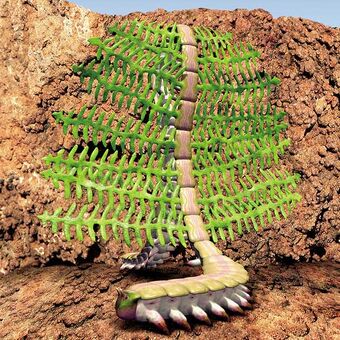

Grass tree:

Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->

Descended from bamboo. Every summer their seeds travel via the winds (like grasses today) with fibers projecting out of their tops to float. They have tough woody stems to withstand the wind.

I actually asked my plant biology professor about this today in class. She said that while bamboo doesn't exhibit secondary growth for woody stems/trunks, she said it wasn't completely out there to evolve it. Final verdict: plausible.

Poggle:

Taken from speculative evolution wiki->

A small rodent that feeds upon the grass seeds collected by silver spiders, and killed and eaten by them once they're fattened up.

This little mammal is probably the plainest, most unremarkable and normal-looking creature in the entire series. But it's not its appearance that makes it controversial...it's the fact that it's the last mammal on Earth. Or at the very least, one of the last mammals on Earth. But...is that feasible? I had to sit down and think about this one for a bit, and my opinion is

(Fun fact: that's not what our friend Pirate Captain here actually says in his respective film. But it works to convey my thoughts, so yeah, I'm using it.)

A common criticism I see of this basically amounts to "how can the mighty mammals almost die off?". And there's some amount of truth to that. Mammals -- indeed, vertebrates as a whole (more on that later) -- are tough cookies. They are definitely adaptable animals that have ended up adjusting themselves to the various conditions on Earth at least since the middle Jurassic, if not the Late Triassic. At the same time, however, people have pointed out how highly successful and evidently adaptable groups that lasted a long-ass time have fallen by the wayside before. In the Lower Cambrian, trilobites rapidly diversified and over several hundreds of millions of years had adapted to a variety of different niches. Yet they eventually began a long decline to the point where, just before the Permian-Triassic extinction event, only two genera remained (relying on Wiki for this info, mind you). Even a hardy, adaptable clade could decline and go extinct if circumstances are severe enough. The question just is, does the show provide a sufficient explanation for mammals declining over the last 100 million years (mostly in the last 95 million)?

The show seems to argue that, in addition to extinctions going today, the increasingly warming climate of the hothouse Earth will mean that mammals (even the most successful ones like the rodents) will lose their present-day competitive advantage. Hmmmmmmmm. Well, two criticisms I've seen for this are:

1.) Mammals have adapted to increasingly warmer global temperatures before (Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum).

2.) Why would mammals be at a disadvantage in this hotter Earth when also-endothermic birds are still doing well?

Two counterpoints I've seen to these are

1.) The show's Earth 100 million years in the future is supposed to be hotter than the Eocene (I don't actually know just how hot they wanted this world) and that many mammal groups (~40%->) seem to have gotten smaller during the PETM (in fact, it happened again during a subsequent global warming event called Eocene Thermal Maximum 2; mammalian body size decreased to a lesser extent because the magnitude was not as great->), while birds and reptiles seem unaffected (don't know of any data about this, though). So if it gets even hotter and hotter, this might lead to the world's mammals not doing as well and largely being small.

2.) Birds lay eggs, so they don't have issues with their fetuses overheating during pregnancy. I might be able to add something else to this: it's often been said that unlike fur, feathers also help with keeping cool. And at least from what I can find (link->), there actually seems to be some truth to this.

Maybe I'm being dumb for entertaining the thought of mammals not being in the best conditions in 100 million years' time. Or maybe I have a point (I'd really appreciate some fact-checking). But while I won't completely rule out mammals undergoing serious decline in the distant future if environmental conditions get severe enough (who knows what in the future could do that), I somehow doubt that the conditions stipulated in the show would be enough to wipe out Mammalia to as little as one species. Final verdict: implausible to extremely implausible (broad stroke).

Alright, that's it for 100 million CE. Wait...what's that rumble?

Oh yeah, at the end of this episode, a horrible mass extinction takes place due to increased volcanism. The companion book has a particularly vivid description of this event.

"The temperature of the Shallow Seas falls and the prevailing currents fail. Ocean phantoms deflate and die. Reef gliders shrivel for lack of food. In the Bengal Swamp, plants wilt and are incinerated by blasts of white-hot ash, while cold-blooded toratons stand motionless, their vitality seeping away in the cold. On the Antarctic continent, flutterbirds choke in the poisonous atmosphere. High on the Great Plateau, the webs of the silver spiders hang limp and torn, deprived of their seasonal influx of seeds. Great blue windrunners are grounded and flap helplessly in the face of storms generated by the climatic disruption. It looks as if all life is doomed."

I don't know where it gets this from, but the Wikipedia page for TFIW's episodes claims that 99% of all life on Earth at this time period goes extinct. If that's even possible (especially for the next era's fauna to evolve), this might indeed put even the P-T event to shame. It's apparently so bad that all tetrapods go extinct. I have at least a couple questions, but this can be discussed in a later post. I'm just going to say this: strap yourselves in. 100 million years later, it gets even more wild. Whether in a good or bad way...that's up to you.

Great blue windrunner:

Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->

A giant (3 meter wingspan) crane descendant that is metallic blue, and an annual migrant to the great plateau for breeding. It is this color because at high altitudes, there is little protection from UV light. The metallic blue plumage helps reflect UV light and protect the bird. The nictitating membranes are polarized to protect the eyes from UV light, effectively making them organic sunglasses. Windrunners can tell other individuals apart by looking at distinctive UV light patterns on their plumage (being able to see in ultraviolet). The other notable thing about this bird is that it has four wings. The trade-offs associated with wing morphology and function have become too much in this ecosystem where the plateau stretches for thousands of kilometers and reaches higher up than the Himalayas today (>12,000 meters above sea level), conditions no bird today has to live under. The great blue windrunner needs to be both fast (and presumably energetically efficient when flying fast) and maneuverable at the same time. So the bird uses just its two forewings (long and narrow, like those of a condor) when soaring great distances over the vast plateau at high speed. But when it needs maneuverability (like when it needs to see the ground better at lower speeds), it spreads its feathered hindlimbs out laterally. What this does is it effectively gives the windrunner more wing area when needed, which can be retracted back when greater soaring speed is needed again. Also, the bird has small feathers on the sides of its neck (right behind the head) called canards, which stabilize the head during flight. In the great plateau, it preys upon the silver spiders.

There’s nothing about this bird that jumps out at me as implausible. At first I was wondering why this bird has suddenly cheat coded the trade-offs of wing morphology and function (and having the best of both worlds) but this is explained as a result of the fact that no bird alive today has to live in conditions this harsh, which I can excuse. The four wings I can pass considering we have feathered theropods from the fossil record with just that (look no further than Microraptor). Final verdict: plausible.

Silver spider:

Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->

Very self-explanatory name. The silver is this spider’s way of reflecting harmful UV light. Oh, and they're also larger than today's spiders (by how much I don't know). They construct large webs spanning across the canyons of the great plateau, numbering in the hundreds (pretty sure these are different families/groups). To create webs this large, silver spiders not only work together, but are divided amongst different caste depending on their age and size. There are those that cast the first lines (they are smaller), those that cast the actual webs (larger), and the massive queen that stays inside their rock crevice home and lays eggs. These large webs trap many seeds from the grass trees that float via the wind. They use this to feed the poggles that live in the rock crevices with them. After a certain point, poggles are killed and fed to the queen.

I'm using the opinion of someone else I've read online to guide my final verdict. While the colonial aspect of the silver spiders' behavior may be believable, their farming of poggles is...not, really. This person pointed out that, while there are ants that raise aphids, aphids are very simple creatures that mostly reproduce by basically cloning themselves (asexual reproduction, I assume) and don't move very much if it's not necessary. A poggle is a mammal, and almost certainly going to be more mobile and curious, thus a lot harder to farm by some spiders. Final verdict: very implausible (there creature, I used it lol).

Grass tree:

Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->

Descended from bamboo. Every summer their seeds travel via the winds (like grasses today) with fibers projecting out of their tops to float. They have tough woody stems to withstand the wind.

I actually asked my plant biology professor about this today in class. She said that while bamboo doesn't exhibit secondary growth for woody stems/trunks, she said it wasn't completely out there to evolve it. Final verdict: plausible.

Poggle:

Taken from speculative evolution wiki->

A small rodent that feeds upon the grass seeds collected by silver spiders, and killed and eaten by them once they're fattened up.

This little mammal is probably the plainest, most unremarkable and normal-looking creature in the entire series. But it's not its appearance that makes it controversial...it's the fact that it's the last mammal on Earth. Or at the very least, one of the last mammals on Earth. But...is that feasible? I had to sit down and think about this one for a bit, and my opinion is

(Fun fact: that's not what our friend Pirate Captain here actually says in his respective film. But it works to convey my thoughts, so yeah, I'm using it.)

A common criticism I see of this basically amounts to "how can the mighty mammals almost die off?". And there's some amount of truth to that. Mammals -- indeed, vertebrates as a whole (more on that later) -- are tough cookies. They are definitely adaptable animals that have ended up adjusting themselves to the various conditions on Earth at least since the middle Jurassic, if not the Late Triassic. At the same time, however, people have pointed out how highly successful and evidently adaptable groups that lasted a long-ass time have fallen by the wayside before. In the Lower Cambrian, trilobites rapidly diversified and over several hundreds of millions of years had adapted to a variety of different niches. Yet they eventually began a long decline to the point where, just before the Permian-Triassic extinction event, only two genera remained (relying on Wiki for this info, mind you). Even a hardy, adaptable clade could decline and go extinct if circumstances are severe enough. The question just is, does the show provide a sufficient explanation for mammals declining over the last 100 million years (mostly in the last 95 million)?

The show seems to argue that, in addition to extinctions going today, the increasingly warming climate of the hothouse Earth will mean that mammals (even the most successful ones like the rodents) will lose their present-day competitive advantage. Hmmmmmmmm. Well, two criticisms I've seen for this are:

1.) Mammals have adapted to increasingly warmer global temperatures before (Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum).

2.) Why would mammals be at a disadvantage in this hotter Earth when also-endothermic birds are still doing well?

Two counterpoints I've seen to these are

1.) The show's Earth 100 million years in the future is supposed to be hotter than the Eocene (I don't actually know just how hot they wanted this world) and that many mammal groups (~40%->) seem to have gotten smaller during the PETM (in fact, it happened again during a subsequent global warming event called Eocene Thermal Maximum 2; mammalian body size decreased to a lesser extent because the magnitude was not as great->), while birds and reptiles seem unaffected (don't know of any data about this, though). So if it gets even hotter and hotter, this might lead to the world's mammals not doing as well and largely being small.

2.) Birds lay eggs, so they don't have issues with their fetuses overheating during pregnancy. I might be able to add something else to this: it's often been said that unlike fur, feathers also help with keeping cool. And at least from what I can find (link->), there actually seems to be some truth to this.

Maybe I'm being dumb for entertaining the thought of mammals not being in the best conditions in 100 million years' time. Or maybe I have a point (I'd really appreciate some fact-checking). But while I won't completely rule out mammals undergoing serious decline in the distant future if environmental conditions get severe enough (who knows what in the future could do that), I somehow doubt that the conditions stipulated in the show would be enough to wipe out Mammalia to as little as one species. Final verdict: implausible to extremely implausible (broad stroke).

Alright, that's it for 100 million CE. Wait...what's that rumble?

Oh yeah, at the end of this episode, a horrible mass extinction takes place due to increased volcanism. The companion book has a particularly vivid description of this event.

"The temperature of the Shallow Seas falls and the prevailing currents fail. Ocean phantoms deflate and die. Reef gliders shrivel for lack of food. In the Bengal Swamp, plants wilt and are incinerated by blasts of white-hot ash, while cold-blooded toratons stand motionless, their vitality seeping away in the cold. On the Antarctic continent, flutterbirds choke in the poisonous atmosphere. High on the Great Plateau, the webs of the silver spiders hang limp and torn, deprived of their seasonal influx of seeds. Great blue windrunners are grounded and flap helplessly in the face of storms generated by the climatic disruption. It looks as if all life is doomed."

I don't know where it gets this from, but the Wikipedia page for TFIW's episodes claims that 99% of all life on Earth at this time period goes extinct. If that's even possible (especially for the next era's fauna to evolve), this might indeed put even the P-T event to shame. It's apparently so bad that all tetrapods go extinct. I have at least a couple questions, but this can be discussed in a later post. I'm just going to say this: strap yourselves in. 100 million years later, it gets even more wild. Whether in a good or bad way...that's up to you.