|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 16, 2020 19:32:50 GMT 5

I've recently gotten a little interest back in the 2002 docufiction The Future is Wild, having downloaded a digital version of the companion book (although, it looks to be a different version of the companion book) for my iPad a few weeks ago. TFIW holds a special place in my heart due to being one of the first speculative evolution works I've ever heard of. Plus, even after 18 F***ing years, it remains one of the few televised programs about speculative evolution. At this point, it's probably the most famous venture into speculative evolution ever (there's the actual program, companion book, a kid's show, a former exhibit in France, and even a manga!). Now, the first thing I want to make clear is that the very first episode (of the original British version) states that we do not know if any of the future species hypothesized will happen, but that they could. In other words, the series is not so much claiming "this will absolutely happen" as it is "here's a plausible possibility". However, looking back at the series, some ideas are clearly more plausible than others. Besides, this should not stop us from pondering whether or not the hypothesized species are feasible. So, just for fun, I’m going to list every hypothesized species in this series and provide my verdict on how plausible it is, whenever I have the time. For now, I am thinking of using three simple ranks to rate each species: “ plausible”, " intermediate (plausibility)", “ implausible”, " very implausible", and “ extremely implausible” (this is subject to change in the future). Two caveats must be kept in mind: 1.) I am not an expert, and 2.) I am not going to get into whether or not they get their geology right, since I’m even less of an expert in that, but which I’m sure is a hell of a lot easier to predict in the future than what species will exist (so I honestly trust that they’re about right in this regard). Other members are free to post their own input (and correct me if needed) as well. Anyway, I’ll start this topic with the first ecosystem featured on the show. Return of the Ice (5,000,000 CE):Shagrat:  Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->Basically a herbivorous, sheep-sized descendant of the marmot that has adapted to the future ice age of Europe. Thick woolly coat (like a muskox or woolly mammoth), incisors and broad claws for digging through the snow, and lives in herds. Okay…I guess that’s not too bad. I mean, it wouldn’t be the first time a rodent has evolved much larger body size and filled up a rather specialized niche (*cough* Josephoartigasia *cough*), and I don't think a tundra-specialized form is really that far-fetched. Whether or not social behavior would evolve I don’t know, although it honestly doesn’t seem inconceivable. I do wonder what happened to the ungulates of the Anthropocene (which I may consider as more viable candidates of filling this niche); did they all go extinct like in Dougal Dixon’s After Man? They don’t really elaborate on this too much to my memory. Overall, I’ll rank this as plausible. Snowstalker:  Taken from the Speculative Evolution wiki->Supposedly a tiger-sized (its size seems to be inconsistent; the American Animal Planet version claims it to be 75 lbs) saber-toothed mustelid, descended from the wolverine. Again, fine, not too bad. I may take a little issue with their specific description of how it kills its prey, because I don’t think it’s quite an accurate reflection of how actual sabertooths did this; the snowstalker launches an ambush attack, retreats to a reasonable distance to avoid injury, and lets the victim bleed to death while following it wherever it goes after the attack. Real sabertooths used powerful forelimbs to wrestle with prey and land a killing bite to a vital region (e.g. the throat); I don’t think retreating to avoid injury was part of that repertoire. At the same time, however, this precautionary behavior honestly doesn’t sound all that far-fetched, so the snowstalker could still incorporate it (although, how would a shagrat seriously injure a snowstalker? Biting or clawing it?). Final verdict: plausible. Gannetwhale:  Taken from the Non-alien Creatures wiki->An aquatic gannet descendant that has evolved to fill the niche of now extinct marine mammals; it only goes up on land for breeding. First and foremost, I somehow doubt marine mammals would all be gone in 5 million years’ time. While some marine mammals today are certainly under threat, it looks like enough today are not. Looking at cetaceans, even if we assumed all 27 data deficient species are threatened (read: vulnerable or worse), ~47% of all species (not counting subspecies) are not threatened. [1] It appears that a large number of pinnipeds are also not under threat. [2] So while I certainly think a good proportion of marine mammals won’t make it long enough to produce descendants lasting 5 million years into the future, I don’t think cetaceans and pinnipeds are so endangered as a whole that they’d be completely extinct by this time. It is possible that humanity lasts somewhat longer (say, by a thousand or few thousand years) and more species become threatened in that time frame, but obviously that's not something we can easily confirm. Secondly, I question whether or not the gannetwhale’s pinniped-like bauplan could evolve from a flying bird in only 5 million years. In fact, I’m not sure such a bauplan would necessarily need to evolve at all. Instead of lying on their abdomens like pinnipeds do, known aquatic flightless birds have/had an upright stance and are/were still bipedal when they walk(ed) on land (e.g. penguins, great auks, plotopterids). Why not evolve to look more like that? Certainly such a bauplan would seem more likely to evolve from a competent flying bird in just 5 million years than that of a pinniped. Final verdict: implausible (as much as I like the gannetwhale). [1] iucn-csg.org/status-of-the-worlds-cetaceans/[2] www.mmc.gov/rapcon/ |

|

smedz

Junior Member

Posts: 195

|

Post by smedz on Feb 16, 2020 22:02:11 GMT 5

This is good! The shagrat is probably the most plausible I think. But I think the wolverine might take a niche similar to a bear while lynx evolve into the sabertooth niche.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 16, 2020 22:18:08 GMT 5

I agree with smedz. That's gonna be a great post series. And very reasonable so far.

Can't wait 'til it gets to the squiddies as well as the often-criticized mammal-breeding spiders.

|

|

|

|

Post by DonaldCengXiongAzuma on Feb 17, 2020 6:33:29 GMT 5

That’s interesting. I like the gannetwhale best.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 17, 2020 8:02:17 GMT 5

The Vanished Sea (5,000,000 CE):Cryptile:  Taken from here->I chose this image specifically because I thought it best demonstrates how this thing hunts, which is arguably the most distinctive thing about this speculative reptile. This lizard hunts brine flies (which are still around 5 million years hence), getting both nutrients and moisture from them. To hunt them, the cryptile runs bipedally (with a relatively upright posture) into masses of flying brine flies with its wide neck frill spanning outwards (it can fold the frill inward. This neck frill is covered with a sticky wax secretion, which allows the frill to trap the brine flies like flypaper. As it’s running, the cryptile uses an extremely long tongue to lick up the flies caught on its frill and consume them. It lays its eggs in the crevices of the karst ecosystem, to prevent them from shriveling up on the salt plains. Finally, males also use the size and color of its neck frill for mating displays, competing against other males and mating with females if they can keep up with them during a running ritual. I’m on the fence on this one, since I don’t know whether or not evolving a sticky external substance on the neck frill would be plausible or not. Final verdict: intermediate (see creature386's post below). Scrofa:  Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->It’s a wild boar descendant, but smaller than its ancestor (half the height of modern wild boar, according to the original British documentary), has a longer and narrower snout to stick into the crevices of its karst habitat to reach for food, thinner and more elongated leg bones, and walks on the very tips of its hooves like a duiker (or a ballerina, if you will). I guess this one gets a pass. Suids indeed seem to be rather adaptatble animals, especially with regards to their diet; I especially liked the narrow snout to reach for any food item available in hard-to-reach places (and considering it eats cryptile eggs, it’s still an omnivore like its ancestor). The stance of the animal is a little weird, but given how we have a precedent of sorts in the duiker, I guess I’ll let this pass. Final verdict: plausible. Gryken:  Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->Another predatory mustelid (this time descended from the pine marten) with a sinuous body designed to easily maneuver through the crevices of the karst habitat. It's got some pretty long upper canines itself->, to the point where these teeth are exposed when the mouth is closed (although they're definitely proportionately shorter than the snowstalker's fangs). The gryken hides in the crevices watching over scrofa herds. It never attacks adults, but will attack juveniles. Okay, fine, I guess it gets my pass as well. Pine martens already seem to have long, sinuous bodies (as do some other mustelids like weasels and stoats), so it's not far fetched for me to see this turn into an adaptation for maneuvering through rock crevices. The cautiousness of this predator may be a little extreme IMO -- it apparently never attacks adult scrofa, which are seen acting aggressively to grykens (is the size difference still too much?) --, but whatever. Final verdict: plausible.

|

|

smedz

Junior Member

Posts: 195

|

Post by smedz on Feb 17, 2020 19:18:11 GMT 5

While a pine marten ancestry isn't impossible, I think it would make more sense for a ferret to be the grykens ancestor since already being on the ground the evolutionary path would be shorter.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 17, 2020 21:39:57 GMT 5

I'd say a creature is still plausible if all you have to do is to slightly swap out the ancestor species.

Anyway, this post series is a nice way for me to keep track of the creatures we saw in that show. To be honest, I had almost forgotten about the vanished sea. Since I remember the next two episodes rather well though, I have something to look forward to.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 17, 2020 22:01:31 GMT 5

I hadn’t considered the point about the gryken’s potential ancestor, but yeah, overall an idea I’d still rank plausible.

How likely do you lot think the cryptile’s sticky neck would evolve? That was the most troubling thing to think about.

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 18, 2020 2:18:21 GMT 5

I've been googling for sticky skin and frills in animals and it seems like animals at most evolve sticky feet or sticky tongues. Glue traps for insects seem to be more of a plant thing.

Then again, I don't see any reason why an animal shouldn't be able to develop glands to produce the sort of secrets that would trap insects. I don't know how to classify the cryptile. It's not in the "this-is-most-likely-to-happen" category, but it doesn't violate any known law of biology or evolution either (unlike some of TFIW's later creations).

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 18, 2020 2:54:23 GMT 5

Okay, I've labeled the cryptile as intermediate in plausibility, and have added that as a fourth rank between "plausible" and "implausible". It will be a useful rank for some later creatures.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Feb 18, 2020 18:04:34 GMT 5

Maybe something like the adhesive pads on Gecko feet would make the most sense? Reptiles tend to not evolve too much in the way of skin glands (not saying it’s impossible though), but this would seem well-suited to the task at hand. Did they specifically say it was a glandular secretion (and also not which version it was that I watched)?

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 18, 2020 18:23:16 GMT 5

I'll have to check the documentary later when I get the time (both the British and American versions, just in case the latter has any proposals). I'll edit this post once I do. EDIT: the American Animal Planet version seems to exclude "The Vanished Sea" entirely (I'm starting to see why creature386 almost forgot about it). The original British version just says it's a waxy secretion. So I'm assuming the sticky substance does originate from cells or glands. theropod |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 18, 2020 23:02:46 GMT 5

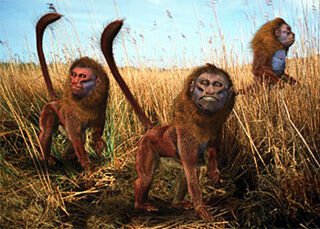

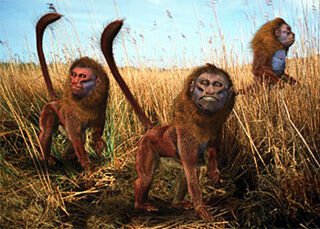

Prairies of Amazonia (5,000,000 C.E.)Babookari:  Taken from the Speculative Evolution wiki->A descendant of the uakari that has adapted to a terrestrial lifestyle on the plains of the former Amazon rainforest. It retains the red face of its ancestor (but with what appear to be blue markings), but also now has a blue chest and blue buttocks that are all used for signaling through the tall grass. The tail is supposedly raised vertically and used for this purpose too (although, I'm looking at the British doc right now, and I don't think they say this?). It lives in troops, meaning more eyes looking for food and predators. The babookari's limbs are long and supple for efficient locomotion while foraging through the open plains. Also, it weaves crude baskets made from grasses to use as fish traps. Finally, it is apparently among the last of the New World monkeys. First I want to address the whole "last New World monkey" thing. One criticism I have heard for the whole "last primate"/"last New World monkey" thing is that current human impact wouldn't be enough to kill almost all New World monkeys off in 5 million years' time. I think this criticism misses the point: the babookari isn't the last New World monkey simply because of human impact. It's the last New World monkey because the geography and climate have changed such that the Amazon rainforest has turned into a grassland (and very quickly might I add, within a few thousand years according to the original British program). As a result, many modern animals residing in the Amazon rainforest have gone extinct, with the babookari's ancestor, the uakari, being adaptable enough to survive. I have no way of knowing for sure, of course, but I wouldn't be surprised if many, if not even most, New World monkeys went extinct as a result of this change in habitat. However, there is one criticism I do agree with: the uakari is actually under threat. The bald uakari, which I assume is the ancestor of the babookari (given how it's the one of which footage is shown, and due to the babookari's inheritance of a colored-face), is currently listed as 'vulnerable' under the IUCN Red List, and its population is currently decreasing [1]. Some alternative ancestors have been suggested by other people; if a few New World monkey species are able to survive the recession of the Amazon rainforest, I could conceive one evolving into a babookari-like lifestyle. Then there's the coloration/markings and raising the tail up as a visual signal; wouldn't these make babookaris far easier to spot (especially by carakillers, which, as sauropsids, should have excellent color vision)? Does the size of the troop looking out for danger outweigh this probable disadvantage? And lastly, there's the whole weaving fish baskets thing: while I haven't reviewed all scientific literature documenting primates hunting fish, I don't think any strategies as complex as weaving baskets for capturing fish are used. Primates can catch fish either by hand or by using stick tools (i.e. jabbing at the fish in an attempt to startle it, prompting it to jump out of the water and letting the primate feed upon it) [2][3]. Weaved baskets not needed. Final verdict: intermediate at most, if not bordering towards implausible. Carakiller:  Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->A ~3 meter tall terror bird-like descendant of the caracara. Its arsenal consists of a massive hooked beak that smashes into prey, as well a single sickle-shaped claw on each manus (oddly enough, the carakiller seems to be depicted with pronated "bunny hands", something usually and erroneously drawn on Mesozoic theropods). The feathers on its head can fold up and down, and are used for communication. Perhaps most striking of all, it hunts gregariously, using rather sophisticated, coordinated strategies to take down prey like the babookaris. The first thing we may want to ask ourselves is "Would the carakiller be able to evolve when there may very well be carnivorous mammals that could fill in the apex predator niche?". There are precedents for large flightless carnivorous birds coexisting with large mammalian carnivores. Most bathornithids were flightless and seem to have occupied apex predatory roles in North America from 37-20 million years ago; during this time, large mammalian predators were definitely around in the continent. Also, Titanis is known to have lived in the southern United States from ~5-2 million years ago [4], meaning it would have coexisted with large carnivorans for roughly 3 million years. By no means do I think a large flightless predatory bird is unable to ecologically coexist with and compete with large mammalian carnivores, but the fact that competition for the apex predator niche could very well exist makes me wonder whether caracaras would venture into this direction or not. The smashing raptorial beak I can absolutely pass (*cough* phorusrhacids *cough*). The clawed hands... why, though? Now, birds can indeed evolve specialized weaponry on their wings (e.g. knobs, strong club-like wing bones, spurs), and a surprising number of them do indeed have the digit I claw on their manus [5] (not sure about caracaras specifically, though), so I don't think it's inconceivable that a digit I claw that is retained could actually evolve to become a weapon. But...why would a carakiller need them? The flightless predatory birds we know of seemed to have done fine without weaponized wings, and any claws that were used for predatory purposes were on the feet (especially in the case of phorusrhacids). Not something that's totally implausible but...I just don't see a huge need for them. And lastly, there's the cooperative hunting strategies of the carakiller. Honestly...I don't think it's that far-fetched. Predatory birds can use rather complex cooperative hunting strategies (see the Harris' hawk), although the amount of species that do this indeed seems to be quite limited. Final verdict: intermediate. South American rattleback:  Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->This is a rodent descended from the agouti. No longer having the dense rainforest for cover, it evolved heavy plates on its back for defense (derived from fur that matted together and became solidified). These plates can move individually, and the noise that results is where the rattleback gets its name. Territorial rattlebacks can rattle these plates for display against each other. It also has a row of spines on each of its sides below the plates; these are planted into the earth, with muscles controlling them locking them in place. This way, the rattleback cannot be flipped over. It is seen raiding the nest of a carakiller (for the eggs, of course), and its plates are durable enough to withstand a blow from the bird’s beak. Question: why a rodent? There are actual armored animals in South America today that already have the armor (duh) and could modify it to be rattleback-like (for whatever reason that might be). Why would a rodent, of all mammals, suddenly evolve it? Interestingly, the agouti is already considered a cursorial animal [6]. When the rainforest turns to open grassland, I could easily see the agouti becoming even more cursorial and using speed as its primary antipredator defense. Seems more likely to me than evolving armor seemingly out of nowhere. Final verdict: implausible. [1] www.iucnredlist.org/species/3416/9846330[2] sci-hub.tw/10.1007/s10764-007-9176-y[3] sci-hub.tw/10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.06.007[4] Revised age of the late Neogene terror bird (Titanis) in North America during the Great American Interchange[5] scienceblogs.com/tetrapodzoology/2010/06/30/clubs-spurs-spikes-and-claws[6] Forelimb proportions and fossorial adaptations in the scratch-digging rodent Ctenomys (Caviomorpha)

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 18, 2020 23:39:24 GMT 5

I did not expect this to move into the realm of the implausible so quickly yet. Nice to see that at least my beloved carakiller got off comparatively well.

Alright, that's it for today's Episode. Next up are the mega-bats, bunny-moles (?) and some third creature (northern rattlebacks?). I think I remember the stuff after that a bit better.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 19, 2020 4:38:14 GMT 5

Actually, I want to get one more in for today (I really want to get into the next era, even though I don't know how to judge many of them). I've also added a new rank 'very implausible' (between 'implausible' and 'extremely implausible'). Cold Kansas Desert (5,000,000 CE)Desert rattleback:  Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->This is another species of rattleback that evolved from the South American species, which I already covered. Rattlebacks were so successful in the South American grasslands that they migrated up north. They've actually changed to adapt to the cold, sandy deserts. There aren't as many large predators threatening the rattlebacks. Accordingly, they are less heavily armored than their South American ancestors, with smaller, more closely linked plates. However, this armor, coupled with a face covered in thick fur, is still useful as protection against sandstorms. Also unlike its immediate ancestor, it has a long tail that serves as fat storage (permitted to evolve due to the lack of large predators that could grab it). It is seen digging up tubers, which provide both food and water for them. None of what I said matters, because I've already deemed the South American rattleback to be implausible. Because the desert rattleback evolved from the South American species, my final verdict is that it is implausible by association. Spink:  Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->The descendant of quails, but smaller. It has smaller feathers acting as insulation (like mammal fur). Its face has very fine feathers keeping sand and dust out of its eyes. It is a flightless quadrupedal bird that uses its modified wings as hard spades to dig through the soil. Spinks spend most of their life digging burrows underground and finding tubers for sustenance. They live in big colonies and have a caste system with workers and breeding females. Their beaks are very short and blunt/rounded at the tip. They are preyed upon by deathgleaners, when rattlebacks dig through the soil and accidentally fish out spinks near the surface of the burrow. At night, when the deathgleaners are inactive, male spinks will emerge out of their burrows first, displaying by flapping their modified wings; the females emerge later and move to find a group of unrelated males. Females choose their mates. This is an extremely unprecedented morphology among birds scratch that, theropods as a whole. A quadrupedal burrower??? Although it is an extreme morphology, I don't think it would necessarily be impossible (but certainly not likely) to evolve...if there weren't already better candidates for the niche, that is. Three out of five prairie dog species ( Cynomys spp.) are listed as 'least concern' by the IUCN, and it looks like most North American gophers are fine (i.e. not threatened) as well. I see no reason why these could not have descendants surviving 5 million years into the future and claiming the social burrower niche (a quick search suggests gophers are not social, though). Final verdict: implausible, if not very implausible due to the fact that a quadrupedal build is so unprecedented among theropods (I'll give the spink this, though: it's definitely a cool idea for a hypothetical quadrupedal bird and kind of cute). Deathgleaner:  Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->A diurnal carnivorous bat with a 1 meter wide wingspan. It preys upon spinks that are exposed to the surface by rattlebacks, and even on immature rattlebacks. Adult rattlebacks are shown to be too much for them to handle; their sharp armor plates can easily damage their fragile wing membranes. Deathgleaners also scavenge. When temperatures drop to freezing at night, the deathgleaners return to their roots in caves and even share food with each other. This way, unsuccessful hunters can still eat. Although it has very thin, wide, naked wings that could lose a lot of heat in the cold desert, the deathgleaner has a countercurrent system in its forelimbs, where blood is relatively cold in the wings but warmed up as it enters the body. Again, there are already better animals that could fill in this niche. There are diurnal North American raptors alive today (that still have relatively favorable conservation statuses) that both hunt and/or scavenge. I admittedly did not look into the conservation status of every single one, but the fact that there are a handful that are doing relatively well today, coupled with the fact that I see no reason for them to not adapt to the changed environmental conditions of the former American midwest, makes me think that a big diurnal carnivorous bat isn't exactly the most likely to evolve. Final verdict: implausible.

That wraps up our time in 5,000,000 CE. One final note before we jump 95 million years in the future: what I had not known prior to today is that in TFIW-verse, the ice age ends around this time period (so not too long after) and the world becomes much warmer->. Many specialized species go extinct accordingly (this includes the specialized tundra and arid desert species); the so-called "Age of Mammals" ends here. This results in the hothouse Earth we will see 95 million years later. At this point, life on Earth gets even more wild...and less realistic, to put it mildly. |

|