|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 21, 2020 22:39:57 GMT 5

Probably. Maybe I just took issue with the whole "cephalopods conquer the land" issue in general. It does make sense within TFIW's premises that vertebrate place eventually gets displaced though.

|

|

|

|

Post by dinosauria101 on Feb 22, 2020 0:00:54 GMT 5

Well, I was talking to Infinity Blade when I said that.

TBH, if not for the outlandish size figure, I could see a smaller Toraton working out.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 22, 2020 0:24:17 GMT 5

I'm pretty sure all of them still have eight normal tentacles and more importantly don't have a supposedly lung-like specialized lining that enhances breathing on land. Dragonthunders did a redesign of the toraton. For what it's worth, he envisions it as a semi-aquatic, still sprawling giant turtle that amasses 3 tons. The largest terrestrial testudine was Megalochelys, which apparently amassed anywhere from a tonne to 2 tonnes. If real life body mass was closer to the higher end, I might be able to see a 3t giant testudine working out (don't quote me on that, though). Some amount more if it evolves erect legs, but how much more is the question. www.deviantart.com/dragonthunders/art/Redesing-of-TFIW-Toraton-620895531 |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 23, 2020 4:54:24 GMT 5

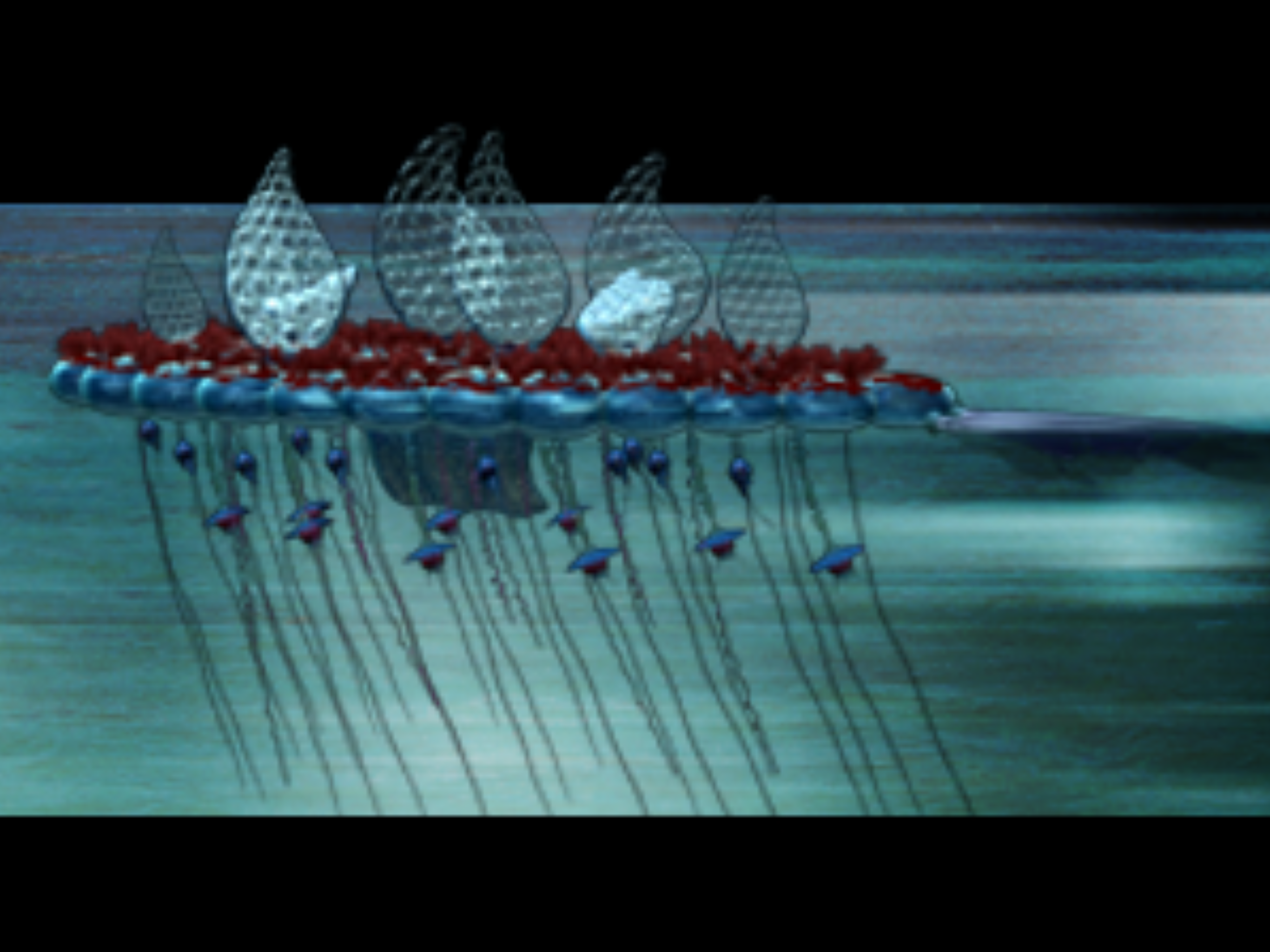

Just so everyone knows, this is my least confident review so far. That I’m just one guy voicing my own opinion on these hypothesized species has never been more apparent until now. But then again, the species from this episode are so damn weird and alien. Flooded World (100,000,000 CE)Ocean phantom:  Taken from the Fictional Animal wiki->A huge (typically 10 meters long and 4 meters wide according to the 2003 companion book) physaliid siphonophore descended from the Portuguese man o’ war, and the largest animal floating on Earth’s oceans. Like its ancestor, it’s really a colony of animals. For those not aware let me provide this brief explanation: the Portuguese man o’ war is composed of four polyps (highly specialized animals of the same species). The first polyp is the gas-filled bladder on top (from which it gets its name), the second polyp is composed of the venomous tentacles, the third polyp contains gastrozooids (digestive organisms), and the fourth polyp contains the reproductive organs [1]. The polyps are attached to one another, cannot survive on their own, and therefore have to work together to function as a single animal. But the ocean phantom takes this to a whole new level. See the blue sails on the very top? Each one of those sails is one individual animal (and their function is exactly what they look like). Those blue circular bases of the sails? Those are the floats (filled with carbon monoxide so that the phantom doesn’t sink), and each float is an individual animal. The purplish rudders at one end? Again, each is a highly specialized individual animal. The tentacles underneath (which are submerged in the water and catch prey)? Again, each (bundle?) is an individual animal. To navigate across the waters, the ocean phantom can pump water into its sails to raise and lower them, and can turn these sails depending on the wind’s direction. The individual sail animals are able to do this because the man o’ war’s nerve net evolved to become more elaborate, connecting all the different individuals into one massive network. Underneath the water are also the ocean phantom’s feeding apparatuses. It has developed “hunting bells” that act as the colony’s mouths, suspended on cables that can retract. These “bells” also have eyes of some sorts that let the phantom see its prey. The bells widen and suck prey into them, then close as their cables pull them back up. Though it’s the largest predator of the shallow sea, the ocean phantom itself is hunted by a lot of animals. The primary target for predators is the crop of red algae on top of the floats, which generate carbohydrates and feed every individual in the colony. Secondarily, the air bags and water sacs contain some animal proteins, though they’re not particularly nutritious. One predator of ocean phantoms is the adult reef glider, the young of which are preyed upon by the siphonophore. To defend itself from larger threats like reef gliders, the ocean phantom has a symbiotic relationship with sea spiders called spindle troopers (see further down below). When a violent storm breaks out, the colony can break apart. However, the ocean phantom can simply regrow and reproduce as long as a broken off piece still has individuals of each type of part. To be honest…I just don’t know. But I do wonder what kind of ecological pressures would force the ocean phantom to be so large. Any good reason as to why? Or is this just a “rule of cool” thing? ( EDIT: okay, going by theropod's post below, the size could simply be a product of adding more individuals, so maybe it's more plausible than I thought) Final verdict: undecided, maybe intermediate or even plausible?Spindletroopers:  Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->Sea spiders that have a symbiotic relationship with the ocean phantom. The spindletroopers live in the “bells” of an ocean phantom, where channels going into the bells provide food for them. So when a reef glider attacks, they come out of the bells and attack the sea slug. They have sharp fangs and slashing claws to irritate and harass a marauding reef glider with until the assailant backs off. This symbiotic relationship seems to have started with the ancestors of spindletroopers living on the algal reefs and sometimes raiding the ocean phantom’s “bells” for food. But now, they live inside the “bells”, and have accordingly evolved a morphology that allows them to fold up inside the “bells”. I feel like the plausibility of this one is heavily contingent upon the plausibility of the ocean phantom. At least from the little I have read, the behavior of the spindletrooper is pretty believable. It's true that no colonial sea spiders exist today, but one person whose thoughts I've read said that there shouldn't be anything stopping them from developing such a social structure. The symbiotic relationship with the ocean phantom I guess I can pass. It's just a matter of...will there be an ocean phantom in the first place for all these special traits to evolve? Final verdict: undecided, maybe intermediate? Reef glider:  Taken from the speculative evolution forum->A swimming sea slug that, according to the original British program, is 3 meters long and weighs over a tonne (the digital book I have describes it as seal-sized, and it seems female elephant seals are 3 meters and 900 kg, so I guess the two statements are broadly consistent). Not quite as brightly colored as its ancestors, but much more mobile, and adults are carnivorous predators (eating things like fish and ocean phantoms, more on that later). Adults will use the horns on their heads to pick up the scent of prey. They swim across the reefs. In contrast to the adults, the juveniles are herbivorous and graze on the reef’s algae. To swim, they have three wings on each lateral side and flap them (imagine a plesiosaur flapping its flippers, except now imagine that it has three on each side and flaps them in turn, with the back ones beating first, followed immediately by the middle ones, and finally the front ones). Juveniles have a symbiotic relationship with the reef-building red algae (see below). There is at least one sea slug today that, instead of living on the sea floor, floats at the water’s surface, the blue dragon. So I feel like it might be possible for sea slugs to make a step forward from floating at the water’s surface to actively swimming and moving independently. What stands out to me, though, is the fact that this thing is as big as a damn seal (at least according to the digital version of The Future is Wild book I have). Nothing alive today that is deemed a “sea slug” is anywhere near that big. Of course, this isn’t proof that the reef glider can’t get much larger. And after all, there have been two-flippered penguins that weighed up to 70-80 kg, and four-flippered plesiosaurs that weighed multiple tonnes. But who knows, maybe it’s possible that there is something I don’t know about sea slug physiology that would prevent a body mass or bauplan like this from evolving. The diet shift from juvenile to adult I think I can pass; if there are vertebrates known to do this, couldn’t a sea slug? Final verdict: undecided; maybe intermediate or implausible? Reef-building red algae:  Taken from the speculative evolution wiki->The reefs of 100 million years in the future aren’t build by corals (which are now extinct). They’re now built by red algae. These algae can grow much faster than corals because of the warm, shallow water getting plenty of sunlight. In order to reproduce over long distances of reef, they have a symbiotic relationship with juvenile reef gliders. The red algae have flower-like conical structures from which juvenile reef gliders feed off of. But when they move on to another “flower”, the reef gliders carry the pollen (sperm cells?) of the red algae and actually pollinate other red algae. This is basically a flower-insect/bird/bat relationship, just replace the flower with future red algae “flowers”, and the pollinating animal with a free-swimming sea slug. I’m even less of an algae expert than I am an invertebrate one, but I’ll try my best anyway. Unfortunately, corals going extinct I can absolutely buy (EDIT: okay, that was too extreme of an assertion (see theropod's post below), but I can definitely see something else become the dominant reef builder 100 million years into the future). Even today corals are under serious threat: it’s apparently projected that by 2100, there will be few, if any, suitable coral habitats left, with 70-90% of coral reefs disappearing over the next two decades [2]. These would subsequently be exacerbated by the great changes in oceanic circulation, temperature, and composition as stated in the show. Also, according to Bruce Tiffney on the show, red algae have actually built reefs in the past. From what I can find, it seems that red algae indeed had an important role in building reefs in the past, and in fact, still do today by secreting Mg-calcite for the skeletons of corals [3]. So…I guess it’s not inconceivable for red algae to take up the spot for reef-building themselves? What I’m baffled by, though, is that it basically has its own version of the flower-insect symbiotic relationship with juvenile reef gliders. What do they mean by “pollen”? Is the show saying they independently evolved pollen or is it just referring to the sperm cells ( here's the transcript for the episode if anyone wants to take a look)? Uhh…I don’t know. Final verdict: undecided; maybe intermediate or implausible? [1] www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/p/portuguese-man-of-war/[2] www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/02/200218124358.htm[3] journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0181637 |

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 23, 2020 14:40:41 GMT 5

I'm divided on the algae.

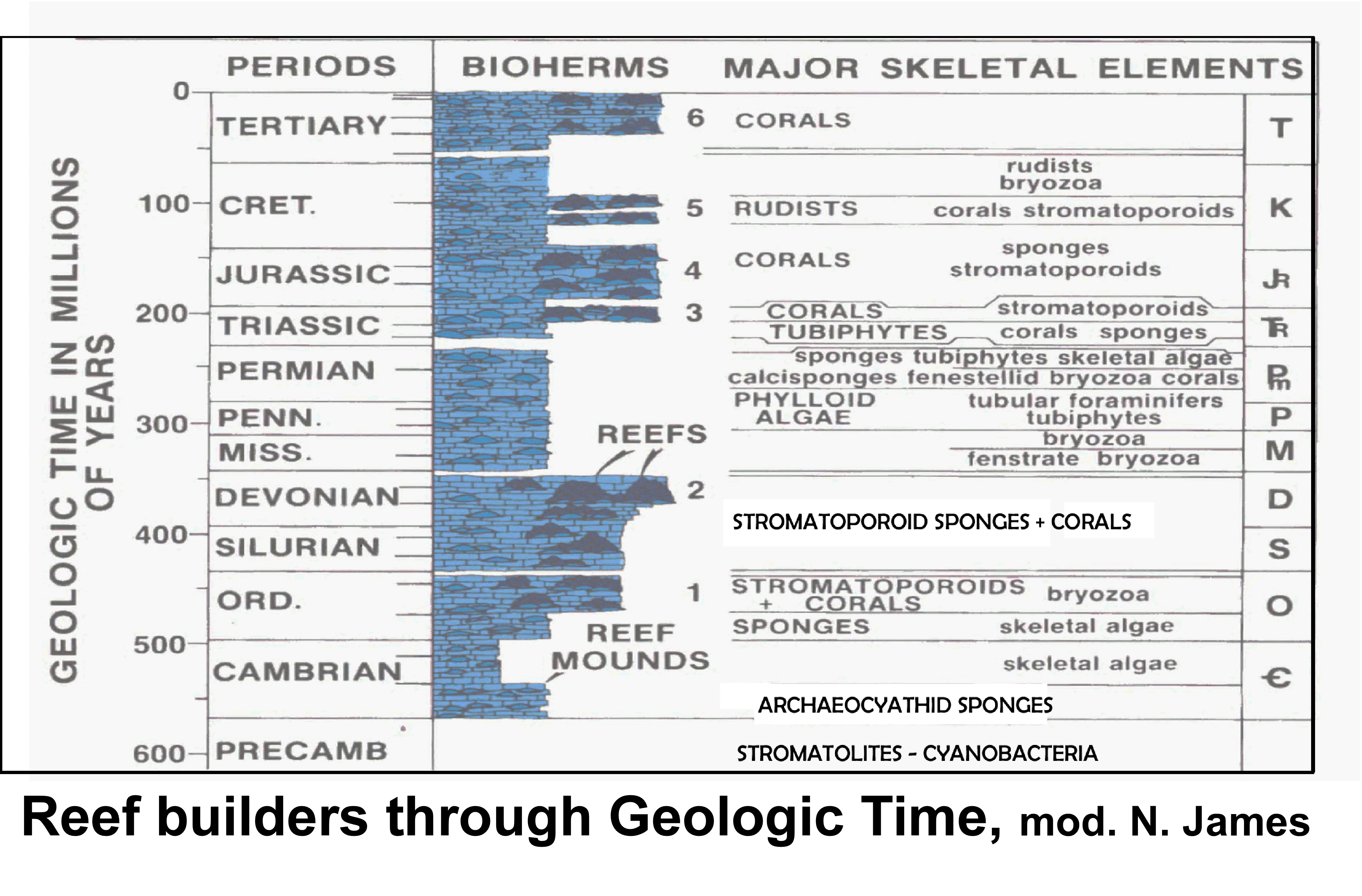

On the one hand, corals have survived for over 500 million years, including events such as the P-T extinction event.

On the other hand, you do have a point that they are already in a bad situation right now.

What I'm confused about is what happened to the fish. After the next timeskip, we see them in the air, but now? Have the reef gliders already replaced them?

The next episodes should be easier to evaluate though. You have a relatively down-to-earth forest that should be easy to rate and after that the ridiculous spider-poggle relationship which shouldn't be hard to rate either.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 23, 2020 19:22:11 GMT 5

Well, the digital companion book I own says that the reef gliders prey upon fish, not to mention the lurkfish from the previous episode, so I assume they're still prominent in Earth's oceans at this point, just not prominently shown here. I think it's possible (but can't prove) the reef glider is one of the few (if not sole) giant sea slugs in an ecosystem otherwise dominated by fish, kind of like how Hatzegopteryx was just one giant pterosaur in an ecosystem that seems otherwise dinosaur-dominant.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Feb 24, 2020 0:53:34 GMT 5

Regarding reef-builders: Earth history has basically alternated between periods where corals were the dominant reef-building organisms and periods where this role was filled by other groups (bacteria/poriferans/algae/bivalves/bryozoans).  source→ source→So I find it totally believable that following the almost certain decline of corals we are facing, likely within our lifetime, some other group could evolve to fill that niche with corals moving into the background (as with everything, this of course also depends on the events surrounding the disappearance of humans). The total extinction of all corals/anthozoans however, far less plausible. Corals have been hit by mass extinctions so many times throughout their evolution, yet anthozoans have always eventually resurfaced as a important reef organisms, and at some point become dominant again. But I think it’s totally plausible that 100 Ma from now reefs would be mostly built by algae, with corals only being a rare or insignificant contributor. Maybe 200 Ma it will be corals as main framework-builders again, who knows. About the phantom: The size may simply be a result of its form of organization. If it just grows by adding individuals, there might not be a set point to stop (unlike in the man o' war, which has a predefined number of individuals making up the colony). Perhaps its size is only limited by mechanics (i.e. withstanding waves and storms). I can’t see any obvious reason why something with this built would have to stop growing of its own accord, or any mechanism for it to do so (on the contrary, growing large and waiting for a storm to rip it apart is basically its mode of reproduction). |

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 24, 2020 1:08:52 GMT 5

Huh. That's something I really didn't know.

What do you think about the red algae's symbiotic relationship with the reef gliders? It's basically an underwater version of the flower-insect relationship. I'll admit that on paper it doesn't sound inconceivable, but I think such a symbiotic relationship is unprecedented underwater.

|

|

|

|

Post by theropod on Feb 24, 2020 3:12:58 GMT 5

Yeah, that doesn’t strike me as exceedingly realistic. Broadcast spermers by and large seem to be doing fine under water, and angiosperm-like coevolution of algae with sea slugs…while not impossible doesn’t sound very likely to evolve, at least not by 100Ma in the future. Plants took an awfully long time to develop that, and it’s probably not a coincidence this evolved on land and not in water.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 24, 2020 8:09:06 GMT 5

The next episode's review is currently in the works. But while I'm in the process of writing it, I'm also thinking about reviewing (in a similar manner) After Man: A Zoology of the Future's animals after I'm all done The Future is Wild. I just downloaded a full PDF of the book onto my computer.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 24, 2020 9:40:16 GMT 5

Tropical Rainforest (100,000,000 CE)Roachcutter:  Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->An agile, maneuverable predatory bird of the Antarctic forest, descended from sea birds that lived during the continent's icy past (in fact, most of the hundreds of birds living here are descended from the Anthropocene's native Antarctic birds). Part of a clade of future birds called flutterbirds. The wings of this bird are short and broad, and it's so fast that it can even catch insects off branches midflight. Apparently, its beak is tough to crush the exoskeletons of its insect prey. According to The Living Book, it has chameleon-like swivel eyes to focus in on its victim. Despite it being one of the most ferocious avian predators in the forest, the roachcutter itself is prey to some of the insects, and supposedly has no defense against falconflies (although, wouldn't its extreme agility be a defense against it?). It's literally just a bird. Hardly anything about this thing is unbelievable. In fact, when researching this thing I was a little surprised to learn that it’s apparently one of the most ferocious of the predatory birds in this ecosystem; its bauplan and ecology just seem so banal for a bird. The only thing that’s a little weird are the movable eyes, considering most birds are unable to move their eyes in their eye sockets. But there are known exceptions even to this (great cormorants can apparently move their eyes in their sockets). Final verdict: plausible. Falconfly:  Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->This is a giant sand wasp descendant supposedly as big as a kestrel. It seems to have clawed limbs that can carry (and probably grab) prey. Its middle legs have long spear-like ends; these limbs come together to form one spearing weapon used to impale birds in flight. It has powerful jaws for butchering its prey and a venomous sting, which are 15 cm long maggots. Judging from the show’s description of the falconfly’s reproductive strategy, it is a K-strategist. To accurately find its way back to the nest, the falconfly uses polarized light from the sun for navigation. Their reason for the falconfly getting so large is this ecosystem basically being the Carboniferous all over again: there are greater concentrations of oxygen in the atmosphere. I was sure that this was convincing, but then I looked at the page for Meganeura on Wikipedia, and apparently large meganeurids are still known from the Upper Permian (when oxygen levels were much lower than in the Carboniferous), which appears to call into question the oxygen explanation for large insect size. There are other hypotheses proposed for the presence of giant insects during the Carboniferous. One of them is the lack of flying vertebrate predators at the time. Indeed, one of the sources says “ It is tempting to assume that the extinction and permanent disappearance of giant flying insects right after the Permian is directly correlated with the predatorial threat by the first pterosaurs in the early Triassic.” [1]. Unlike in the Carboniferous, there are still aerial vertebrate predators of insects in the mid-Futurassic (btw yes, that’s what the 200 million year time span of the entire series is called, according to The Living Book and TFIW’s promotional website). Hell, we were just introduced to one. If this hypothesis for the disappearance of large flying insects is true, then it seems unlikely that insectivorous birds still roaming the skies 100 million years in the future would let something like the falconfly evolve. In short, the would-be falconflies and their ancestors would probably be the prey, not predators, of the Antarctic forest’s flutterbirds. Final verdict: implausible. Spitfire bird:  Taken from the Parody wiki->A flutterbird with a defense against falconflies. When threatened, it sprays a hot, poisonous fluid at predators. This fluid is created by mixing two chemicals, each in its own chamber. To spray the fluid out, the spitfire bird squeezes the two chemicals into a reaction chamber in its tubular nostrils (that it inherited from its tube-nosed bird ancestors). The violent reaction of the two chemicals when mixed together causes it to spray out of the bird's nostrils in a stream. The bird gets these chemicals from sipping chemicals from a certain flower. Because these chemicals can't both exist in the same flower (due to the violent reaction), the tree has male and female flowers, each with one of the chemicals. The spitfire bird has to feed from both male and female flowers for its deadly chemical spray. The bright yellow plumage appears to be a signal of the spitfire bird's potential danger to predators, and falconflies are all to wary of them. Awesome idea. But is such a hot, poisonous chemical spray likely to evolve among birds? I'm not really sure. I also have a question regarding the mechanism with which the spitfire bird sprays out the fluid: would the violent reaction of the two chemicals really be enough to send it spraying out of the bird's nostrils? What's stopping the chemicals from just reacting violently and exploding within the bird's nose instead of streaming outwards in one direction? Final verdict: undecided, maybe intermediate or implausible. False spitfire bird:  Taken from The Future is Wild wiki->A flutterbird with almost an identical appearance to the real spitfire bird, but it's harmless. It mimics the appearance of the spitfire bird to fool predators into avoiding it. It even seems to hover near the flowers spitfire birds visit for their chemicals as a further means of fooling predators. Yeah, I can absolutely buy it. While I'm not sure if the species it mimics is plausible, I see absolutely no reason to think birds would be unable to evolve mimicry of dangerous species as defense against predators. Final verdict: plausible. Spitfire beetle:  Taken from The Future is Wild wiki-> Spitfire birds aren't totally immune to predation by insects. Spitfire beetles have wings and wing cases with the same color of the flowers spitfire birds feed off of. Four of them come together and laterally spread their wing cases, so that together, they look like one flower (the wiki has a picture of just one of these beetles). When a fooled spitfire bird comes close enough, the beetles leap out at the bird with their grasshopper-like hind legs, grabbing it with hooked claws, and letting the bird fall down to the ground, where the beetles feed off of it. Not sure. The few opinions I've seen about this kind of cooperation evolving are mixed. Final verdict: undecided. [1] bechly.lima-city.de/Grzimek.pdf

|

|

|

|

Post by creature386 on Feb 24, 2020 21:29:26 GMT 5

Already expected most of these animals to be on the plausible side. Unfortunately, besides the spitfire beetle, they were also on the more forgettable side.

I'm curious about your review of the next episode. Besides the review of the megasquid episode, it's been the review I've been looking most forward to.

|

|

|

|

Post by Infinity Blade on Feb 24, 2020 21:59:58 GMT 5

I actually found most of the animals from this episode rather memorable. It’s hard for me to forget a bird that spews burning fluid from its nose, only a little easier to forget the bird that mimics it, and a giant insect that spears birds to death. The roachcutter is easily the most forgettable one, though. And yes, I’ve been looking forward to the next episode too.  |

|

|

|

Post by dinosauria101 on Feb 25, 2020 5:41:06 GMT 5

The animals in this episode seemed overall very plausible for the most part, I agree.

|

|

|

|

Post by DonaldCengXiongAzuma on Feb 26, 2020 7:38:35 GMT 5

I enjoyed these fictional bird pictures.

|

|